Equipment

Where Have All the Sensors Gone? Assessing the Global Oxygen Sensor Shortage

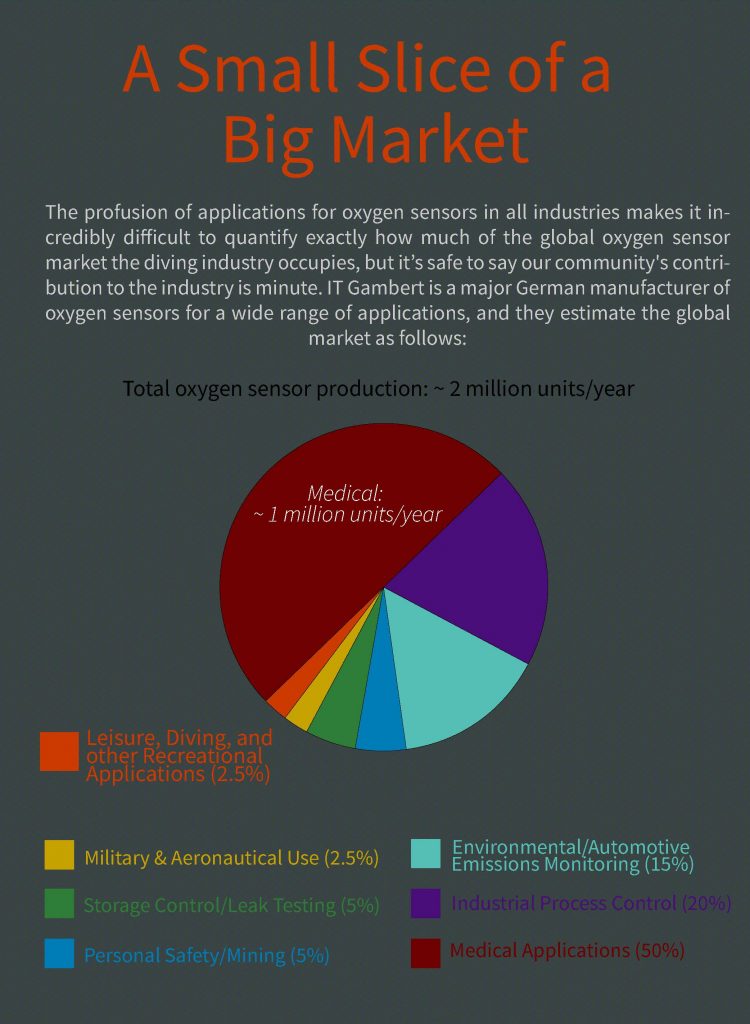

Tried to purchase O2 sensors for your rebreather lately—to no avail? You are not alone. As Reilly Fogarty explains, there’s both a global shortage of sensors as well as long lead times because of the pandemic-induced medical demand. Note that diving applications account for less than 2.5% of global usage.

By Reilly Fogarty

Header image courtesy of AP Diving

Our community has weathered a number of drastic and unexpected changes this year, not the least of which is the current shortage of oxygen sensors for gas analyzers and rebreathers. These electro-galvanic oxygen sensors were first developed in the 1960s and have found uses in the automotive, medical, scientific, and manufacturing fields as well as at home in our dive kit. However it’s the pandemic-induced demand in the medical field that has posed the most recent challenge to the sport diving community.

The types of galvanic oxygen sensors used in rebreathers are nearly identical to many of those used in medical devices, and even those that differ in form often share the same structure and manufacturer. The most common use for these sensors can be found in medical ventilators and anesthesia machines. These devices pump air, usually with an increased fraction of oxygen, into a patient’s lungs to help oxygenate their tissues and support life when they cannot breathe for themselves. The patients are anesthetized and intubated—an endotracheal tube is placed in their airway to prevent airway obstruction—and the ventilator is used to push air into their lungs via a bellows system.

As COVID-19 symptoms progress in some patients and they develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the alveoli in their lungs fill with fluid and they lose their ability to adequately oxygenate themselves. This, and other complications that result in a patient losing the ability to breathe on their own, requires the use of a ventilator to maintain life. These ventilators, anesthesia machines, and a wide array of associated devices used for pulmonary interventions all require the careful monitoring of oxygen exposure.

For many of the same reasons that divers manage their oxygen exposure, physicians must carefully monitor the time spent breathing and the fraction of oxygen they give their patients. CNS toxicity isn’t typically a concern in these situations, but long-term oxygen exposure can lead to a litany of inflammatory responses and damage to the pulmonary, ocular, and circulatory systems.

An Unprecedented Demand for Sensors

The result of the influx of serious COVID-19 cases is that these ventilators and other medical devices that require oxygen sensors have been put under unprecedented demand. Machines are being repurposed, pulled from storage, and manufactured at breakneck speed to meet an impossible need. Researchers are innovating new solutions to provide care in areas where ventilators cannot be used or sourced as well, but even while ventilator bellows can be redesigned, the inspired gas must be measured with oxygen sensors.

The result of the influx of serious COVID-19 cases is that these ventilators and other medical devices that require oxygen sensors have been put under unprecedented demand. Machines are being repurposed, pulled from storage, and manufactured at breakneck speed to meet an impossible need.

This means the few companies that do make oxygen sensors for diving uses, like Vandagraph and Analytical Industries, have had to put their normal business on hold and retool their manufacturing to meet medical demands. The logistics of this are immense, but the products are quite often similar; medical oxygen cells can sometimes share the same connectors as some rebreathers, and many differ only in the way they’re attached to a device.

Despite what your dive buddy’s Salt Life bumper sticker may imply, diving is a recreational sport—at best a professional endeavour—so it’s difficult to find fault with the industry’s redirection of oxygen sensor supplies and manufacturing. All the same, it’s frustrating not being able to access the sensors we need to keep diving, and there’s undoubtedly a temptation to inappropriately extend sensor life in the face of a shortage. [Ed note: JUST SAY NO!]

It’s easy to see how diving applications get lost in the scope of the industry, but Eugenio Mongelli, CEO of TEMC DE-OX, an analyzer manufacturer, says the shortages we’re seeing now are complicated by the choices in sensor compatibility that diving equipment manufacturers have been making. “I do not believe using a custom made oxygen sensor in your analyzer is a good policy,” Mongelli said. “In case you are in the middle of nowhere you must [be able to] replace the sensor with any kind available.” Notably, TEMC DE-OX designs their analyzers to accept a wide range of oxygen sensors for this purpose, and Mongelli contends that applying the same methodology to other diving equipment could alleviate some shortage concerns in situations like the one the industry is facing now.

Supply Chain Blues

At the time of this writing (OCT 2020), some sensors have been available sporadically, but widespread shortages and delays in supply have been noted across the industry. The manufacturing supply chain has been estimated at approximately three months behind schedule, and it’s unclear when the situation will improve.

“Production oxygen sensors have been prioritized toward medical requirements since the pandemic started. Nearly all production has been used to supply government ventilator projects around the world,” explained Ryan Swaine, International sales manager for Vandagraph Ltd., a major manufacturer of oxygen sensors for surface gas analyzers and sister company to Vandagraph Sensor Technologies. “[Vandagraph] has also prioritized some of our products toward the emergency ventilator projects in the UK, such as our VN202 scuba analyzer, which is being used in some of the UK hospitals”.

Rebreather manufacturers have managed to ford the gap in supply in a few ways. Inspiration product manager Nicky Finn, of UK rebreather manufacturer AP Diving, said that AP “views this as a short-term issue” with the hope that “with time, normal stock levels will return. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to predict a time frame for this,” she explained. AP has managed to maintain some supplies of oxygen sensors via the use of two separate product sources, which has resulted in a small waiting list that they are working through as sensors become available.

Pieter Decoene, operations manager for rEvo Rebreathers, has taken a similar approach, noting that maintaining a large stockpile of sensors is not “the best approach, due to the limited shelf life of the sensors.” The rEvo team has found that customers are largely understanding of the shortage, and that while delivery times were somewhat longer, the sensor supply chain has not been entirely lost. “An interesting fact that we saw during the worst of the shortage was that divers who followed the rEvo sensor replacement policy (one sensor replaced every six months) were never forced to stay out of the water for lack of oxygen sensors,” Decoene said, adding that “having true redundancy and following the sensor exchange policy permitted [these divers] to continue diving without compromising safety.”

Photo courtesy of Poseidon Diving Systems

In another interesting turn, Poseidon Diving Systems has seen a shift in the configurations of rebreathers they are selling, from approximately 50% of divers choosing to outfit their unit with a Poseidon Solid State Oxygen Sensor, manufactured for Poseidon, to 100% in recent orders. However, Jonas Brandt, CEO of Poseidon Diving Systems, said that while they do have “a huge order backlog from customers having rebreathers that only facilitate the “old” [galvanic] sensors, [he] does not see any change in lead times. However in terms of quantity, galvanic sensors are being delivered in lots of 25 bimonthly, rather than 200.”

It’s difficult to say exactly when this shortage of sensors will end because, as we enter fall, so much depends on how successful global efforts are in stemming the pandemic. The good news is that there may be a light at the end of the tunnel, as Vandagraph has begun to meet some of their demands from ventilator projects and has begun producing non-medical sensors in small batches once again. Cautious but optimistic, Swaine says that there “is a large backlog to get through, so there are still delays in supply, but the situation has started to improve.”

Another large sensor manufacturer, who did not want to be named, shared that same optimism. “To say that the medical industry has dominated our production for the past seven months would be an understatement. We are running 10-12 hours a day, six days a week and it is still not enough, but both the industrial and diving industries are extremely important to us and we are hoping to have this backlog up to date shortly,” a representative explained.

No matter how hopeful manufacturers may be, Mongelli says that the future availability of diving sensors is unlikely to improve until the global COVID response gains ground. Due to the sheer demand from anesthesia device requirements, he predicts that supplies will remain sparse until next year, when he is hopeful a vaccine becomes available to control the spread of the pandemic.

Dive Deeper:

- Though the outlook on oxygen sensors is challenging, there is some good news on helium availability and supply from GasWorld magazine:

Helium: oversupply leads to ‘a pricing plateau’ - Thinking about become a CCR diver? Learn more about the GUE CCR course.

Reilly Fogarty is an expert in diving safety, hyperbaric research, and risk management. Recent work has included research at the Duke Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Environmental Physiology, risk management program creation at Divers Alert Network, and emergency simulation training for Harvard Medical School. A USCG licensed captain, he can most often be found running technical charters and teaching rebreather diving in Gloucester, Massachusetts.