Community

Out of the Depths: The Story of British Mine Diving

If sumps and solo cave diving are, well, a bit too Brit for you, you may want to consider diving into the perfusion of flooded serpentine chert, copper, limestone, silica, slate, and tin mines that honeycomb the length and breadth of the Kingdom. Fortunately, British tekkie and member of UK Mine/Cave Diving (UKMC) in good standing, Jon Glanfield, takes us for a guided tour.

By Jon Glanfield

Header image courtesy of Alan Ball.

When many think of the UK’s caves, with wet rocks and their penchant for darkness, often the images conjured are of tight, short, silty sumps, that can only be negotiated by intrepid explorers outfitted with diminutive cylinders, skinny harnesses, wetsuits and typically a beard. These are the domain and natural playground of the well-known, highly-respected, Cave Diving Group (CDG).

In truth, much of our sceptered isle’s caves are of this ilk, but there is an alternative for the diver who favours a more conventional rig, extra room to manoeuvre, and perhaps a more team-orientated approach—one that is less than optimal in many of the true cave diving environments of the UK.

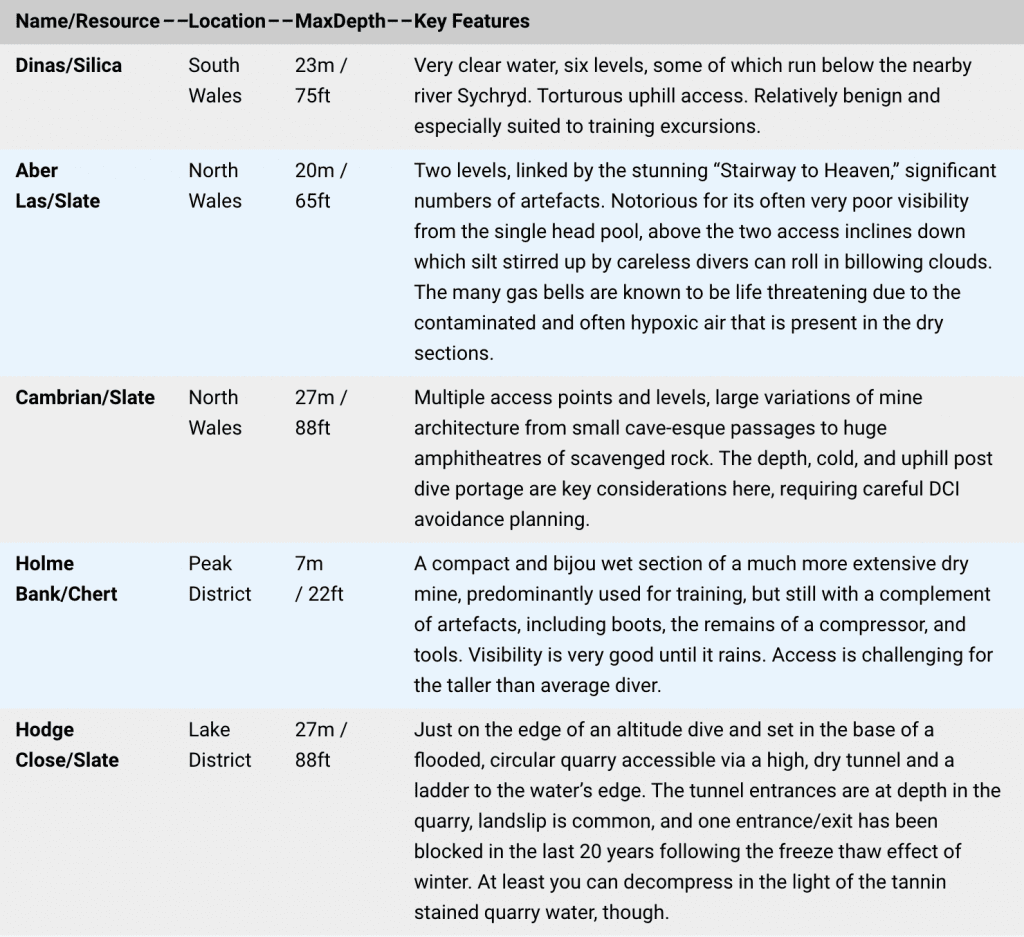

Alongside our natural cave diving venues, we also sport a varied collection of flooded mines across the length and breadth of the Kingdom. In the south and southwest, miners have extracted metals such as tin and copper, while in South Wales it was the mineral, silica. The Midlands Linley Caverns were a source of limestone before being converted to a subterranean munitions store in WWII. Sadly, access to these is no longer feasible. In the rolling hills of the Derbyshire Dales, flinty, hard chert strays close enough to the surface to be mined. In North Wales, the once-proud slate industry has left its Moria and Mithril redolent halls and tunnels beneath the landscape, while copper and slate underlay parts of Cumbria. Meanwhile, just over the border in Scotland, limestone was the resource that drove us to follow its veins into the earth.

Undeniably, here in the UK, mine diving has a much shorter documented history than that of its close cousin cave diving, but some of the luminaries of this dark world were, and are, active in both. Some of the initial dives in sites like the Cambrian slate mine were undertaken by the incomparable Martyn Farr, Geoff Ballard, and Helen Rider in 2006. But it wasn’t until 2014 that it was further explored and lined by the likes of Cristian Christea, Ian France, Michael Thomas, and Mark Vaughan amongst others.

Both Rich Stevenson and Mark Ellyatt, who were part of the vanguard of the technical diving revolution in the UK, had personal dramas on trimix dives in the deep shaft of the Coniston Copper Mines, the depth of which runs to 310 m/1012 ft. Ellyatt made his dive at 170 m/555 ft in the early 2000s in a vertical 2 m/6.5 ft square shaft, dropping away into the 6º C/43º F frigid blackness.

Mines Over Matter

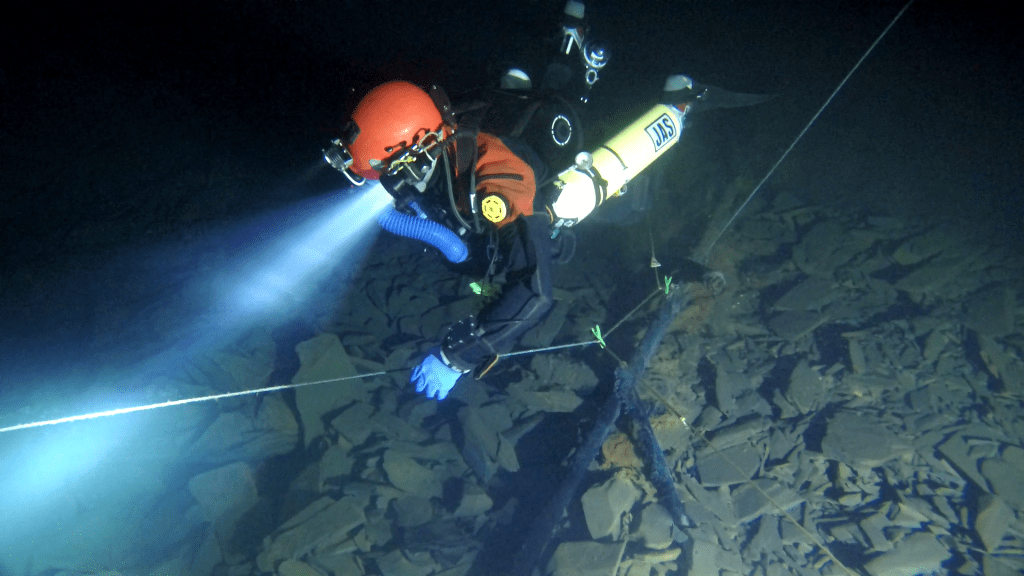

As was alluded to, the differences in cave and mine diving are significant. Conventional, redundant open and closed technical rigs can be employed in mine diving due to the predictably larger tunnels, passages, and chambers. Water movement is negligible, so often regular braided lines can be used, lines which would not endure the flow in many of the UK’s upland cave locations. Small teams can dive in safely.

In general, it is not common to surface and explore the sumped sections of the mines, due to often dangerously contaminated or hypoxic air quality. Also, in some cases, oils and other contaminants have leached into the water. The ever-present risk of collapse—both in the submerged sections and in the dry access adits or portals—haunt divers’ thoughts and is far more common in mines than in the smooth, carved bore of a naturally-formed cave. Casevac (the evacuation of an injured diver) is complex, long-winded, and often dangerous for those involved, and in the event of an issue involving serious decompression illness (DCI), almost certainly helicopter transportation would be necessary given the remote locations.

Landowner access—or, more commonly, denial of access—is an ubiquitous spectre in the underground realm, dry or wet, and much effort is directed at maintaining relations with landowners to safeguard the resources. Some of the most frequented mines are accessible only via traverse of private property, which could be agricultural, arboreal, and in one case, bizarrely on the grounds of an architectural firm. Careful management of these routes into the mines is critical, as is demonstrating respect for the land owner and complying with their requirements when literally on their turf.

At the more prosaic level though, simply getting into some of the mines is a mission on its own, necessitating divers’ decent levels of fitness, the use of hand lines, and sometimes as much consideration of dry weight to gas volume as the dive planning itself. Careful thought and prior preparation are also required in terms of both accident response and post-dive decompression stress, given the exertion expenditure simply to clear the site.

Many of the mines are relatively shallow, mostly no more than 30 m/98 ft with exceptions in the notable and notorious Coniston, and the almost mythic levels in Croesor, extending beneath the current 40 m/130 ft galleries that are known and lined. Though, what the mines lack in depth, they make up for in distance and grandeur.

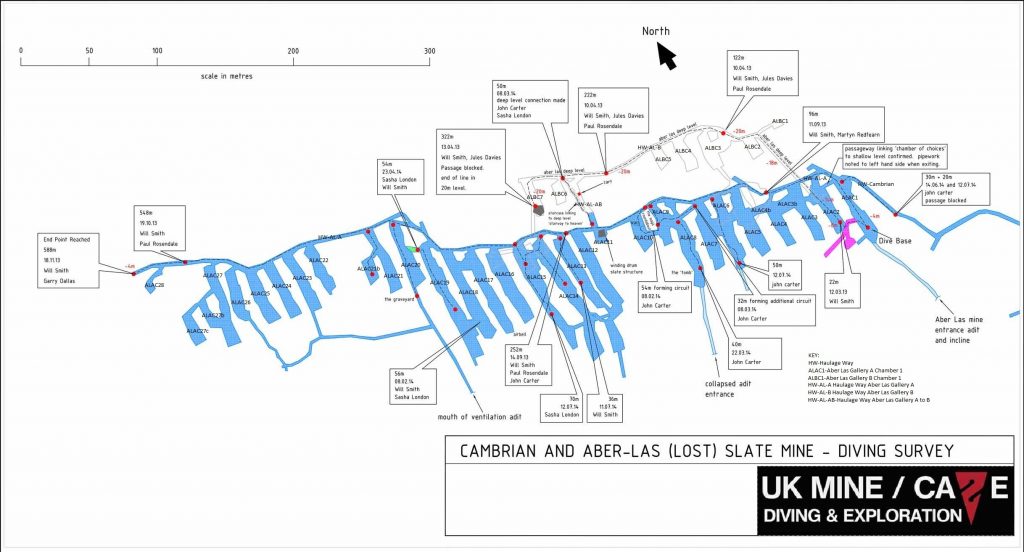

Aber Las, or Lost, is more accurately a forgotten section of Cambrian that extends nearly 600 m/1961 ft from dive base at the 6 m/20 ft level, and a second level 300 m/984 ft long at 18 m/59 ft. The section features no less than 35 sculpted chambers hewn off the haulage ways with varying dimensions and exhibiting differing slate removal techniques. Cambrian’s chambers less than a mile away are larger still, and a lost line incident here could be a very bad day given the chambers’ cavernous aspect.

In The Eye of the Beholder

Beauty is—as they say—in the eye of the beholder, but it would be disingenuous to try to draw comparisons between the UK’s mines and the delicacy of the formations in the Mexican Karst, the light effects through the structures in the Bahamian sea caves, or the sinuous power tunnels of Florida. In mines, the compulsion to dive is due in part to the industrial detritus of man, encapsulated in time and water.

In mines, the compulsion to dive is due in part to the industrial detritus of man, encapsulated in time and water.

Parallels are frequently drawn between wreck diving and mine diving, but often the violence invoked at the demise of a vessel—the massive, hydraulic inrush of fluid and the subsequent impact on the seabed—wreaks untold damage and destruction upon its final resting place. In contrast, nature reclaims her heartlands in the mines by stealth: a slow, incremental and inexorable seep of ground water, no longer repulsed by the engines from the ages of men, gradually rising through the levels to find its table. The result is often preserved tableaus of a former heritage with a rich diversity of artefacts left where last they served.

Spades, picks, lanterns, rail infrastructure, boots, slowly decomposing explosive boxes, battery packs, architectural joinery, scratched tally marks, and, even in some cases, the very footprints of the long-past workers in the paste that was cloying, coiling dust clouding the passages and stairways, can be picked out in the beam of a prying LED.

Spades, picks, lanterns, rail infrastructure, boots, slowly decomposing explosive boxes, battery packs, architectural joinery, scratched tally marks, and, even in some cases, the very footprints of the long-past workers in the paste that was cloying, coiling dust clouding the passages and stairways, can be picked out in the beam of a prying LED.

Underpinning, protecting, preserving, and improving these gems of the realm is the UK Mine and Cave Diving Club (UKMC), which formed as mine diving intensified in the mid 2000s. So it was that Will Smith, D’Arcy Foley, Sasha London, Jon Carter, Mark Vaughan, and Ian France, all of whom are respected and experienced cave divers in their own right, forged the club to foster and engage with a community of like-minded divers.

Sadly, in 2014, Will Smith fell victim to the insidious risks of contaminated air in the Aber Las mine system, which he had been lucky enough to re-discover and in which he conducted early exploratory dives as the club gained traction and direction.

As new members filter into the ranks, new ideas, new agendas, and new skill sets re-shape the club’s direction. At present, we are rebooting the club with a remastered website, focusing on new objectives and seeking opportunities to improve, catalogue, and document the resources we husband.

Exploration continues: the club is laying new line in some areas. What’s more, through our demonstrable respect and care for existing sites, the club is facilitating exploration in previously inaccessible sites, and lost and forgotten sites will resurface. Meanwhile, we’re improving the locations we frequent weekly for the benefit of trainees, recreational (in the technical sense) divers, and survey divers alike. Archaeological projects are rising from the ennui of lockdown; we’re establishing wider links with mine diving communities elsewhere to share techniques, data, and ultimately hospitality.

In Welsh folklore, a white rabbit sighted by miners en route to their shifts was believed to be a harbinger of ill fortune, but for Alice, following the rabbit into its hole led her to a whimsical and magical place. Be like Alice, and come visit the Wunderland!

Dive Deeper:

- Check them out: UK Mine/Cave Diving and Exploration

- Warm Winters and White Rabbits: Folklore of Welsh and English Coal Miners

- The History of the The Wynne Slate Quarry

- Deep Lebel, Deep Water, Deep Trouble by Jeff Wilkinson and Mark Ellyatt

- UKCavediving.com Forum

Jon Glanfield was lucky enough to get his first puff of compressed air at the tender age of five, paddling about on a “tiddler tank,” while his dad was taught how to dive properly somewhere else in the swimming pool. A deep-seated passion for the sport has stayed within him since then, despite a sequence of neurological bends in the late 90s, a subsequent diagnosis of a PFO, and a long lay-off to do other life stuff like kids, starting a business, and missing diving. Thankfully, it was nothing that a bit of titanium and a tube couldn’t fix. He faithfully promised his long-suffering wife (who has, at various anti-social times, taken him to and collected him from recompression facilities) that “this time it would be different” and that he was just in it to look at “pretty fishes.” So far, only one fish has (allegedly) been spotted in the mines. The ones Jon has encountered in the North Sea while wreck diving just obscured the more interesting, twisted metal.