Cave

They Discovered an 11,000-year-old Submerged Ochre Mine

The exploration crew at CINDAQ, headquartered at Zero Gravity Dive Center in Puerto Aventuras made international news this year with their discovery of an ancient submerged ochre mine. Fortunately, they were happy to share the secrets of its discovery and how they documented their find with British cave and 3D photogrammetry instructor John Kendall. Oculus Rifts anyone?

By John Kendall

Header image courtesy of CINDAQ

In 2017, underwater cave explorers Fred Devos, Christophe Le Maillot, and Sam Meacham found evidence of ancient mining activity while exploring and mapping new tunnels of an underwater cave near Akumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Historians know that ancient residents actively mined pigment and other minerals from the caves of the Yucatan Peninsula, but the ancient mines the CINDAQ team discovered are now submerged, indicating that such mineral exploitation occurred thousands of years ago.

At the end of the last Ice Age, intrepid miners ventured deep into these tunnels with torches in hand. The navigational markers, mining debris, fire pits, and excavation pits they left behind are now entirely underwater. Over the last three years, the three explorers (along with others) have been surveying the site and making 3D photogrammetric models of the mine workings. As the mine has been submerged for around 8,000 years, it’s been untouched since then, and it’s an amazing time capsule. The project recently hit the international news when the first results were published. I was pleased to be able to chat with Chris, Fred, and Sam to find out a bit more about the project, and the challenges faced with archaeological work in a cave environment.

John Kendall: How did you happen to find the mine?

Chris Le Maillot: As always, there was a little bit of chance involved with it. The cave—Sagitario, which is a beautiful cave behind Minotauro—was initially explored by a few local cave divers. They established an upstream and part of a downstream, dropping down in the upstream to around 22 m/72 ft, and there’s the halocline sitting at that depth. It’s not always the case, but they didn’t take any survey, absolutely nothing. So I don’t think the information was there for them to continue on with the exploration. As you know, once you have that data in and have a good concept of what the cave is doing and where it’s going, it’s easier for you to poke around and find potential continuations of the cave passages.

So one of the divers asked Fred [Devos] to get involved to create a survey. That comes from the fact that Fred previously had done some mapping for these guys. Fred had a cave survey class coming up, so he took the class there, and spent the week with the survey class mapping the downstream part. Obviously, when they got to the end of the line, Fred could see that there was potential for further exploration. But you can’t really go off exploring during a class, so he went back with Sam [Meacham].

So then you went back and explored?

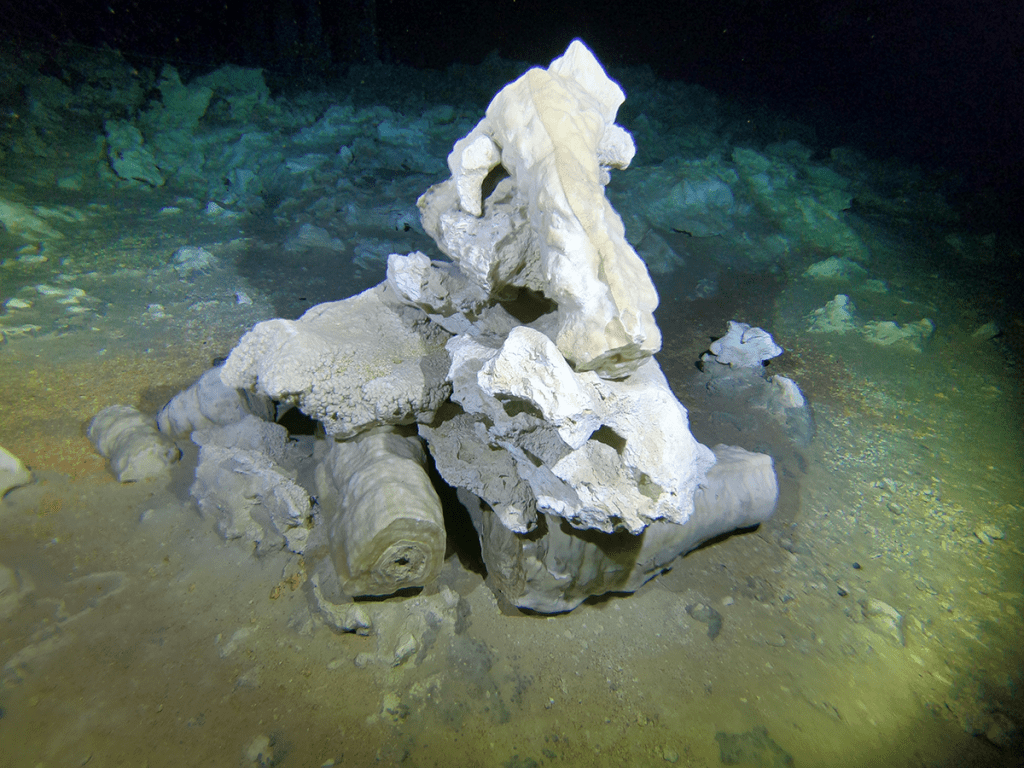

Fred Devos: Exploring caves is what we’ve been doing for more than 20 years, and so it’s a regular event during the mapping of a cave to find more cave to explore. You know, when mapping, we have to swim off to measure the side walls, sometimes there isn’t a wall, and then end up exploring that passage. I was in the process of making a detailed map of this cave, and found this passage, so I went back with Sam, and we immediately realized something was unusual. Things were out of place, we started seeing rocks piled on top of each other, speleothems in places they shouldn’t have been, and the further we went the more of this we saw.

“Exploring caves is what we’ve been doing for more than 20 years, and so it’s a regular event during the mapping of a cave to find more cave to explore.”

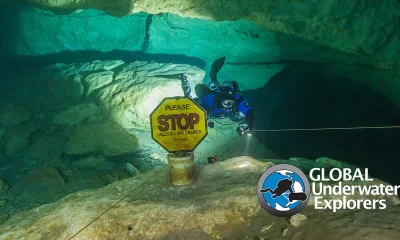

We started picking up a little bit of flow, which is always a good thing in exploration, and that led us to this restriction, where all the water was going through, and I don’t think we’d have made it through if the restriction hadn’t been manipulated before we got there. So, you know, speleothems were smashed out, and it really looked like 100 divers had gone through there before us, which really piqued our curiosity as we knew no one had been there before us. We happened to be in back mount during this dive and I managed to squeeze through there and called Sam through, and that was when we first saw irrefutable evidence of what humans had been doing in this cave—you know, pre-8,000 years ago.

“It was pretty clear to anyone what we were seeing, that people had been digging in here, smashing open the floor and pulling out huge amounts of sediment and piling stuff out of the way. It was super exciting.”

We didn’t have to wait for lab results to come back or ask an archaeologist about it. It was pretty clear to anyone what we were seeing, that people had been digging in here, smashing open the floor and pulling out huge amounts of sediment and piling stuff out of the way. It was super exciting, as it was something we’d suspected for quite a while but had never really determined for sure that was what we were seeing. But this time it was obvious, and there was no question about it.

So, how large an area does the mine occupy?

Sam Meacham: It’s about 250 m/817 ft of cave passageways that are exemplary of the mining activity, and everything we’re seeing there shows the things that people were doing in the mine.

Devos: And we haven’t finished exploring yet. There are hectares of mining area, so it’s not just one hole that’s been dug out. It’s entire passages and we’re talking about hundreds, maybe thousands of tons of material, and remember we have dates spanning maybe a 2,000-year period.

What makes La Mina so significant from a scientific point of view?

Devos: The amount of workings means that this was a massive undertaking. Not just the mining itself, but it’s clear it wasn’t just a one-person adventure. It must have been multi-generational, but beyond that it speaks very much about the organization of the people of that time. So as you can imagine, they were in a dark cave and needed fire for light. So they needed people to bring in the firewood, and others to cart out the material, and there were probably explorers at the time. You know, people that ventured further into the caves away from the exit into the smaller passages…to find this very valuable resource. And I imagine they were the ones that were being punished somehow because the risk involved was probably much greater. So, you know, if they didn’t do their work well in the mine, they probably got sent to explore.

So are there any archaeological signs on the surface around the mine?

Devos: Well there probably are, there’s certainly Maya era archaeology, and in almost every cave we see evidence of that, but we’re talking about 5,000 years ago. The mine was even further back, so anything that was once there won’t be anymore, and the only place we are likely to find anything is in the caves.

Let’s chat about the photogrammetry side. More and more people are hearing about photogrammetry, but I think the readers will be interested to hear a bit more about the challenges that you faced doing photogrammetry in a cave environment, where everything around you is archaeological.

Meacham: I think that can get us started on an interesting concept. In 2010, Chris, Fred, and I, Beto Nava, as well and Franco Attolini and Danny Riordan and Roberto Chavez, all did our underwater archeology course here in Mexico with the Nautical Archeology Society that was supported by the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). It empowered us.

And by having that NAS certification, it kind of helped check a box for the Institute. And, you know, they could say if anybody questioned our abilities, well, we’ve got the certification.

I’d say the genesis of this for all of us here was the Hoyo Negro project, and with the exploration followed by the high grade survey, and then the photogrammetry, which is another whole level in itself. The major problem in Negro is the pit itself—it’s just immense—and how do you document something like that? So we worked with Beto and the team who came up with a grid system at 34 m/110 ft depth, and then it’s every 0.8 m/2.5 ft with a cookie on the line, and so it’s a systematic grid. The difficulty there is that it’s not just a nice flat bottom, it goes from 40 m/130 ft to about 55 m/179 ft, and it just becomes really complex.

But basically what I’ve been doing there is assisting with the lighting or helping Beto. So when we jump forward to doing the mine, it’s a completely different environment. There’s no pit—it’s a continuous cave—so there was no way we could put in a grid, and I’ve never really done photogrammetry before. I had observed it being done, but I was starting from scratch in terms of my own experience. So it was a challenge, but I had plenty of people to go to as resources, and who could check out what I’d done and help make it better. And what’s interesting about the big model is that you can see my progression as we go around, and now of course I want to go back and do it all over again.

So in terms of the challenges, I bought a Sony A7S camera and a Nauticam housing for it, and we just went in and started taking a bunch of photographs, came back, and put it into Agisoft. I have to say my expectations were low, but we were all pleasantly surprised when the model came back. This is like, “Wow that’s what we’re actually seeing there,” and it’s so cool. So that gave me the confidence to say, “I think I can do this,” and we basically picked about 250 m/817 ft of cave passage, which is a great example of the mining activity and of seeing what people were doing there.

That sounds like quite a learning curve, and a big challenge.

Meacham: Yes, we just started going in and piece by piece doing sections of the cave. I can’t remember how long in total we were down there. I’m sure it’s written down somewhere, but we took something around 18,000 photos. And as you know, taking the photos is probably the easiest part. Having the computing power and post-processing of the images is the key. A lot of people treat Agisoft as a bit of a black box, but you know it’s garbage in, garbage out. So in terms of the environment, we’re talking about a ceiling height that’s minimal, and while you can fit through OK, you want to be as high as possible for the photogrammetry in order to cover more area.

“I’m sure it’s written down somewhere, but we took something around 18,000 photos. And as you know, taking the photos is probably the easiest part. Having the computing power and post-processing of the images is the key.”

So, we just worked section by section, using the line as a reference. I was going down the line and started by making sure that I got any markers on it, and then going back and forth to get all the photos. The person that suffered the most was whoever was assigned to dive with me, as they just had to sit there and watch me go back and forth while taking the photos.

18,000 images! That’s a whole lot of processing.

Sam Meacham: Yes, we’re lucky to have the guys at University of California at San Diego (UCSD) helping us with the processing. I probably started off taking too many photos, but the computer guys complimented us on the photos and the overlap and coverage.

So what about other survey techniques, was there anything special about mapping this site?

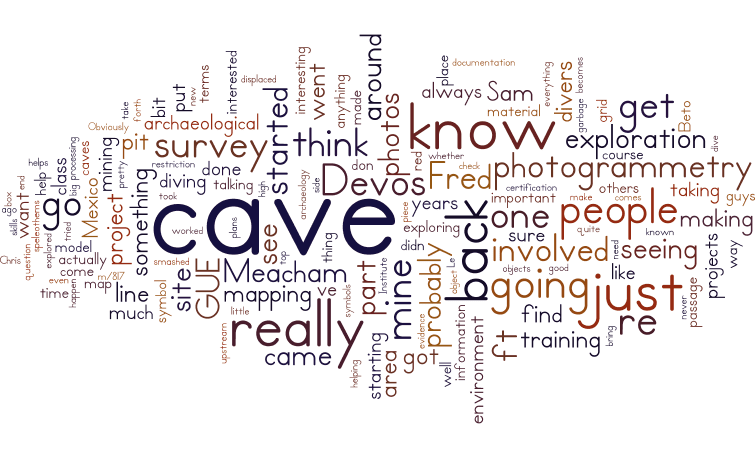

Devos: We surveyed the first part of the cave, and that was pretty normal, but once we found the mine, then suddenly we had a need for all these new types of symbols that didn’t exist before for cave survey. I tried to think about what would be interesting to make notes of, but I didn’t want to speculate as to whether something was a natural pit or whether it was digging.

So we came up with three new symbols. There was already a symbol for a pit, but we added a jagged line on the pit to show that there was a broken edge, so it was smashed. Then we came up with a symbol for a displaced object, so if you see some stalactites and there was no way it came from the ceiling above, then that’s a displaced object. And then if you have stacked objects, so objects placed on top of each other, we had a symbol for that. We then made all of these colored red. I chose red because of the extracted material, the ochre. Also, when you look at the map, and you see all that red, it really shows the extent of the manipulation of the cave. It really brings it out, and I think that’s the most important thing about this cave. Sidewall information is nice, but this is very much an archaeological site.

So what’s next with the site? Any further diving plans?

Devos: We have some plans in place. The map that we’ve made, the photogrammetry, and the video documentation, even the exploration are not finished. So we actually concentrated on one area and tried to get that in the bag, you know, and focus our studies and our samples in that area, without stretching too far, but there’s still a huge portion to go. The technology really helps here, because you can bring that information out for the scientists and others to see. And then there’s much less need for others to go back there.

And this is really the part where we don’t know what’s going to happen. Are divers one day going to be able to go there to tour this site? Luckily, I’m not the one who will be making that decision; there is an archaeological department in Mexico who set the rules. But these conversations are starting, and we’re not really sure where they will lead. But for now we are doing what we can to secure the documentation of the site and working closely with the archaeologists and the landowner.

So a last question: What would your advice be to a diver who is just starting out on their GUE journey, and who hears about this and other projects, and wants to one day join?

Devos: We have been running all kinds of projects down here for years: exploration, science, surveys. Come and get involved, and help out. Good basic training helps open up the door.

Meacham: Once you’ve trained and gained enough experience to become confident in whatever environment you’re interested in, then come and get involved. There’s great training with the GUE Documentation Diver program, Science Diver, Photogrammetry Diver, and Cave Survey where you can actually put these skills to the test. Everyone on a project is an important part of making it work. Obviously it becomes tricky when archaeology is involved, as there can be federal laws and regulations that restrict access, and so we can’t always put just anyone onto a site, but there are all sorts of projects within GUE to help develop those skills and get known by project leaders.

Le Maillot: Of course, project diving is what GUE has been known for since the very beginning. So I think making that initial step to take training with GUE is an important one in the right direction. That’s the starting point of understanding how we are organized, the procedures that we use, [and] the team aspects of all our diving. And then it’s about thinking about what you want to do.

“Of course, project diving is what GUE has been known for since the very beginning. So I think making that initial step to take training with GUE is an important one in the right direction.”

If you’re interested in wrecks, you have Mario Arena in Sicily or Richard Lundgren with the Mars project, and you’re naturally going to be headed down the Tech 1/CCR route. If it’s the stuff in Florida, or Bosnia, or here in Mexico, and the cave thing really rocks your boat, then that’s where the GUE cave training comes in. Then, as you progress with your tech or cave training, you will get to know divers who are involved in projects, and that could be your instructor. You know, if you come here to do some cave diving in Mexico, then Fred is going to mention a few things about survey and cave projects in Mexico and around the world. So that will start opening up a different perspective for you.

Dive Deeper:

InDepth: Data for Divers: Mexican Explorers Go Digital to Chart Riviera Maya

Watch a Video of the Mine on GUE.tv. (Requires a GUE.tv membership or signing up for a free trial)

For more information about the La Mina project, you can visit the CINDAQ website

Check out the CINDAQ YouTube channel

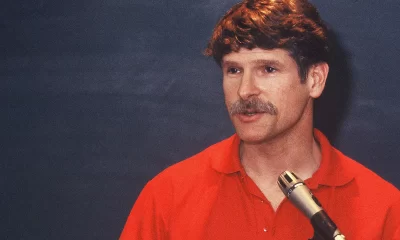

John Kendall is a GUE technical, cave, and CCR instructor living in the UK. Since he was a small child, John has been fascinated by the underwater environment and the possibilities of adventure, and he is grateful to GUE for helping him to turn those childhood dreams into reality. As an instructor, John regularly travels around the world teaching GUE classes and helping to build local GUE communities. For the last 5 years, John has been working with underwater 3D Photogrammetry as a technique for nautical archaeology. This cutting edge technique allows for digital 3D models to be created of shipwrecks and caves, and allows researchers and scientists unparalleled abilities to manipulate and navigate the sites from the comfort of their own computers. John was the primary author of the GUE Photogrammetry class. He is also a member of the GUE Training Council and a Fellow of the Explorers Club.