Exploration

The U-111: The Elusive U-boat

Shipwreck explorer, historian, and author Gary Gentile recounts the extraordinary tale of the search for the elusive U-111 sub—the sole missing shipwreck out of the nine so-called Billy Mitchell wrecks that he and Ken Clayton located and dived in the 90s. It was a search that occupied the deep sea detective for more than 30 years. Despite preliminary pushback from skeptics, Gentile was proven right on June 22, 2022, when the lost sub was finally imaged and identified. Here is his story.

by Gary Gentile. Images courtesy of Gary Gentile unless noted.

The first time I heard about the U-111 was in 1989. I had just started conducting extensive research for two simultaneous projects: the search for the German battleship Ostfriesland and its associated shipwrecks (called the Billy Mitchell Wreck Project), and a book in my fledgling Popular Dive Guide Series titled Shipwrecks of Virginia. The timing was perfect because the Billy Mitchell Wrecks lay off the coast of Virginia.

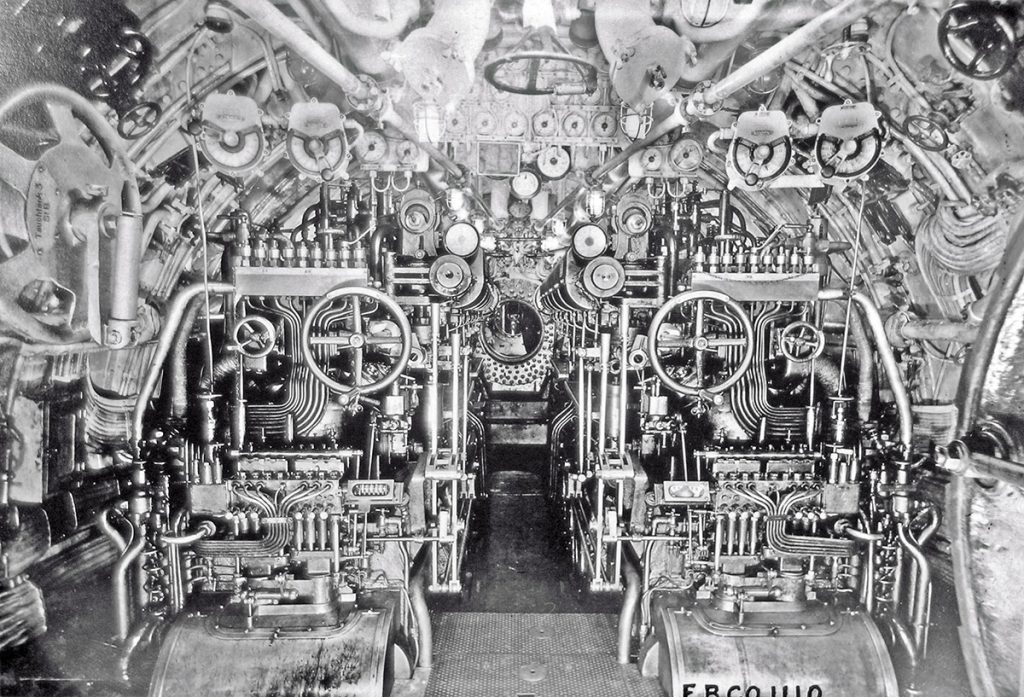

After World War I, the U.S. Navy commandeered 11 warships from the German fleet: the battleship Ostfriesland, the cruiser Frankfurt, three destroyers (G-102, S-132, V-43), and 6 U-boats (U-111, U–117, U-140, UB-88, UB-148, and UC-97). The Navy’s purpose was to study German naval construction and technology. In nearly every case, German warships were found to be more advanced than U.S. warships.

In accordance with the Washington Naval Treaty—which limited the number of warships and the total tonnage that each nation was allowed to have in service—these warships had to be scuttled “beyond the 50 fathom curve” by July 1, 1921. During the interval between acquisition and the prescribed scuttling date, some of the U-boats were examined in detail by naval engineers, while others toured coastal cities for two reasons: to give curious citizens an opportunity to climb aboard a U-boat and walk through its interior, and to promote the Victory Bond Drive, in which citizens were encouraged to purchase war bonds in order to help get the United States out of the debt that had been incurred by the war with the Axis powers.

The UC-97 toured the Great Lakes, after which it was scuttled in Lake Michigan. The UB-88 toured the southern states, then passed through the Panama Canal and toured states along the West Coast; it was scuttled off San Pedro, California. The remaining warships were scheduled to be scuttled in a series of shipboard artillery and aerial bombing tests off Virginia.

Sinking of the U-111

The Billy Mitchell Wrecks Project was created and led by Ken Clayton and myself. Together we did an enormous amount of primary research, not only historical but also gaseous—we had to breathe heliox and trimix because of the extreme depths. Between 1990 and 1995, we found and dived on eight of the nine so-called Billy Mitchell Wrecks: all. . . except for the U-111.

This came as no surprise to us, for in 1989 we had already learned from archival research that the U-111 had not been scuttled with the other Billy Mitchell Wrecks, this because it had already sunk—prematurely, accidentally, of its own accord, and to everyone’s grief—a week before the tests were scheduled to commence.

To backtrack from the disaster described above, after reaching the American coast, the U-111 first participated in the Victory Bond Drive by visiting ports along the New England coast. It then underwent a series of performance tests in which the U-111 outperformed American subs. It was subsequently laid-up at the Portsmouth Navy Yard in New Hampshire.

When it came time for the ultimate test in which the U-111 was to be either shelled or bombed to destruction, it hitched a ride behind the minesweeper Quail. During the 600-mile tow, sailors noticed that the hull kept settling by the head. By the time the vessels reached the Chesapeake Bay, the bow was down by about 4 feet. The U-boat was secured to a piling. A quick inspection of the interior found that the torpedo room was filled with water. The Quail stood by the U-boat overnight while a pump dewatered the compartment. Two hull plugs blew out in the morning, causing the U-boat to settle alarmingly.

Sailors quickly re-rigged the towing lines. The Quail towed the U-boat toward shallow water in an attempt to beach it. The U-boat came to a sudden stop when the bow struck sand and grounded in 5 fathoms/10 m/30 ft of water. And there it stayed. For a year.

The date was June 18, 1921. The scuttling date was four days later. The only salvage vessel in the area was the Falcon. At that time, the Falcon had been working on the salvage of the U.S. submarine S-5 for nearly a year. Not until the submarine was raised or abandoned would the Falcon be available.

Because the U-boat’s conning tower was exposed and liable to collision, a gas buoy with a red flashing light was placed on the wreck. Six mooring buoys were deployed. Salvage of the S-5 was terminated, and the wreck was abandoned. The Falcon arrived at the site of the U-111 on October 1. After a month and a half of hard work, the Falcon was assigned to other duties. She wintered in New York where she underwent a refit. Not until June 1922 did the Falcon return to the sunken U-boat.

Raising the U-111

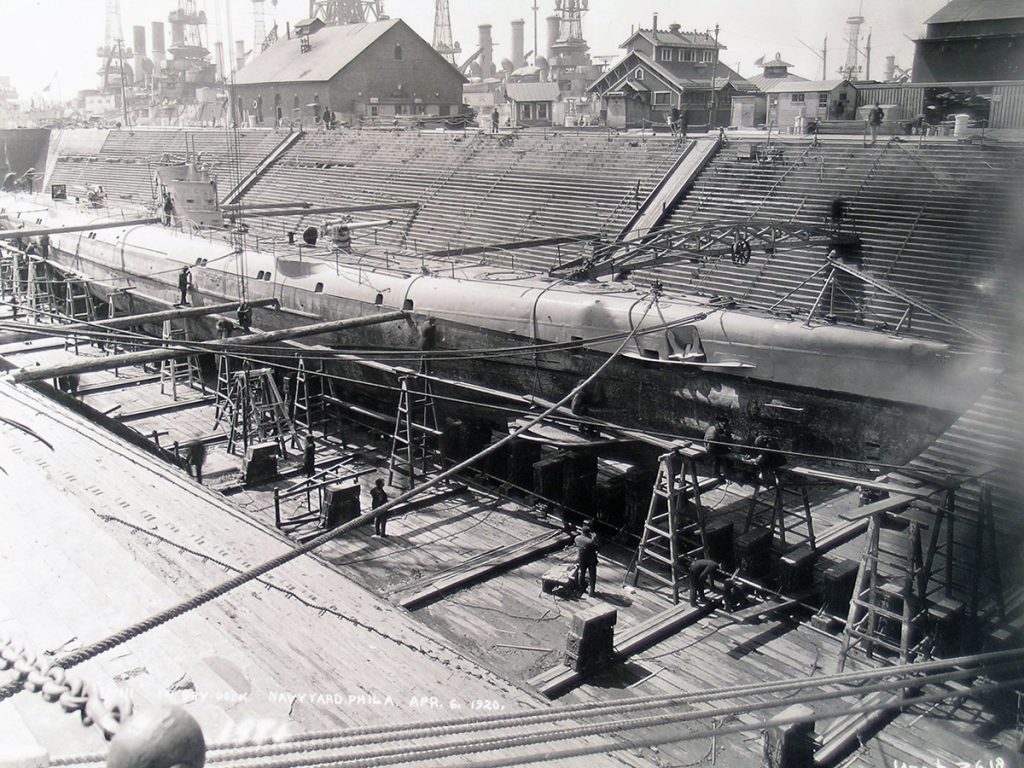

Divers found an open torpedo door and were able to seal it. They also replaced the wooden plugs that had popped out of the pressure hull. On July 29, the Falcon pumped air into the U-boat’s compartments, but succeeded in raising only the stern. On August 4, she towed two pontoons to the wreck site. After much work attaching the pontoons to the sunken hulk, the U-111 was successfully raised and towed to dry-dock at the Norfolk Navy Yard. The battered U-boat was repaired well enough so it could be towed to sea and scuttled.

On August 30, the Falcon proceeded for the Portsmouth Navy Yard with the U-111 lashed to her starboard side. Aboard the salvage vessel was one Mr. H. D. Blaunet of the Pathe Moving Picture Company, who was assigned the task of photographing the U-boat’s final event. Once in the open sea, the U-boat was towed astern on 100 fathoms/183 m/600 ft of wire. The following day, when the Falcon reached the pre-arranged scuttling site, a charge was detonated in the forward battery room. The detonation blew a hole in the pressure hull. Another charge was set in the aft torpedo compartment.

According to the Falcon’s deck log, which I located in the National Archives in Washington, DC, the U-111 sank stern-first in 266 fathoms/486 m/1,596 ft. The coordinates of the scuttling site were also noted in the deck log: 37°45’15” N / 74°07’45” W (or thereabouts, for in those days the only way to determine a position at sea, out of sight of land, was by sextant, chronometer, and a book of mathematical tables).The crew would have taken a sun sighting either at sunrise, noon, or sunset; or a night sighting of the North Star (Polaris), then by dead reckoning: a system of extrapolating the distance and direction traveled from the vessel’s speed, the direction and speed of the water’s drift, and wind’s direction and speed.

When I plotted the coordinates on a chart, I noticed an anomaly: the depth of water at the given latitude and longitude did not correspond with the depth that was recorded in the log; it was shallower by hundreds of feet. So, was the position correct, or was the depth correct? Or neither?

Thirty years passed before I learned the truth.

Finding the U-111

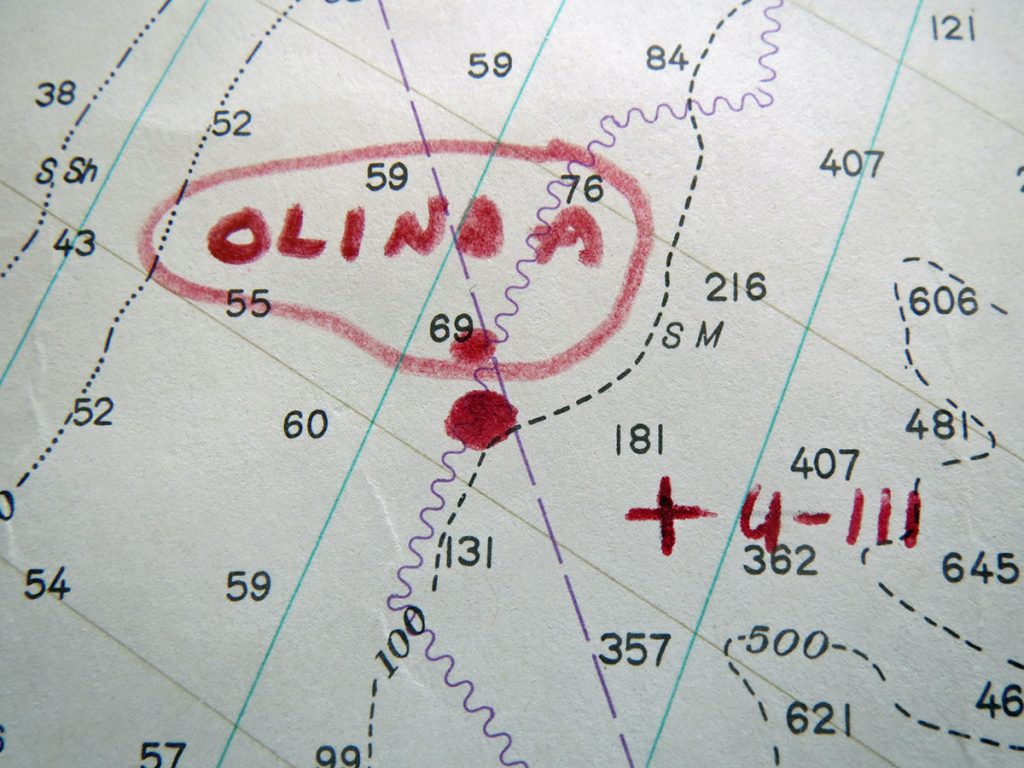

In 2018, my friend Ted Green sent me the coordinates of a commercial fishing site called the Olinda Wreck, believing that it was the remains of a freighter that was torpedoed during World War II. This seemed unlikely in that historical sources placed the Olinda at least 48 km/30 miles from that location. The wreck lay on the edge of the Continental Shelf at a depth of 119 m/390 feet.

When I marked the GPS numbers on my old chart, I saw that the wreck lay only 5.6 km/3.5 miles from the U-111. I thought that was an interesting coincidence. There are so many shipwrecks off the eastern seaboard that there are bound to be wrecks that lie close to other wrecks. For example, popular dive sites Chaparra and San Saba lie only a mile apart. To me, they and the U-111/Olinda represented little more than a curiosity.

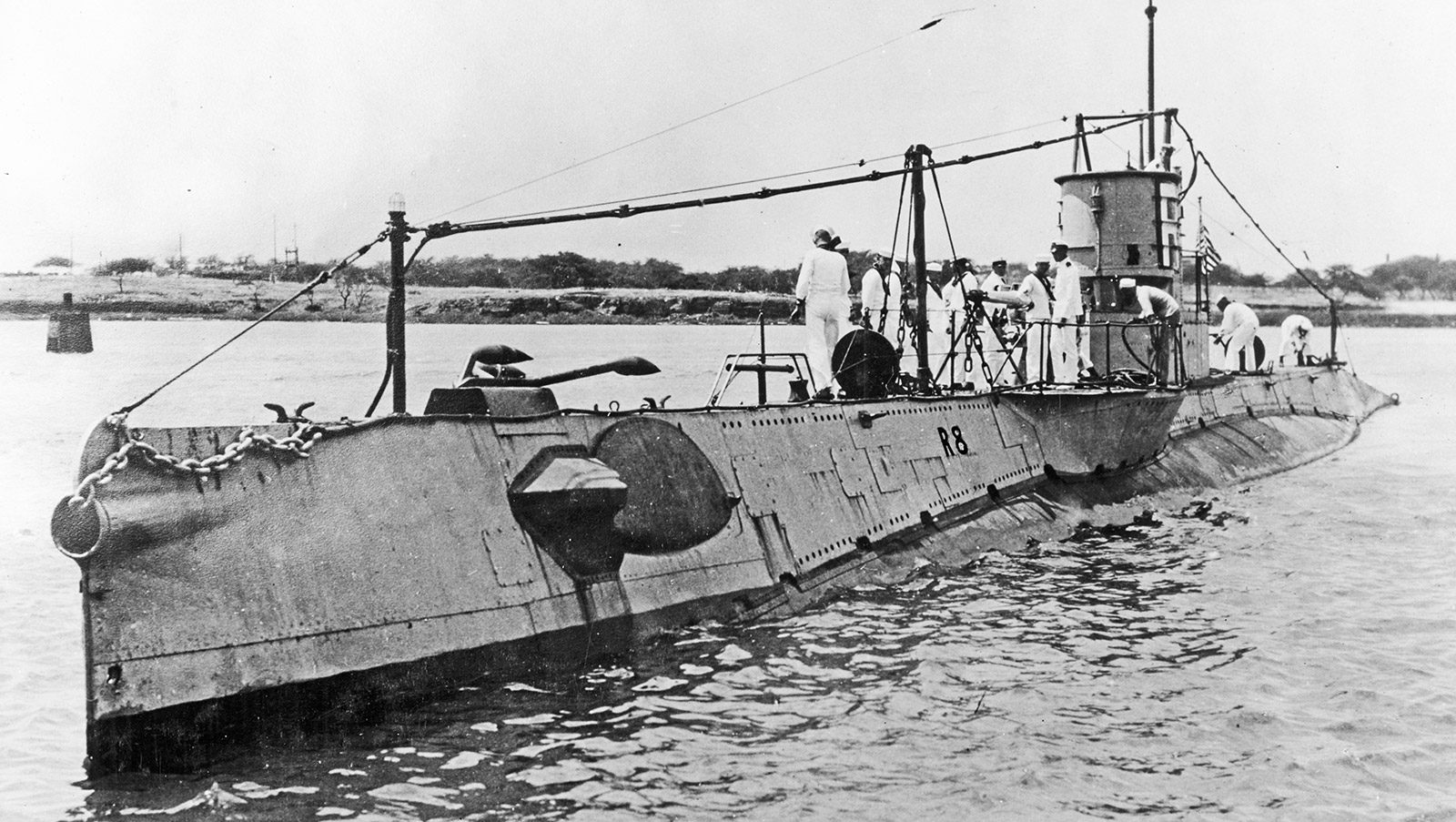

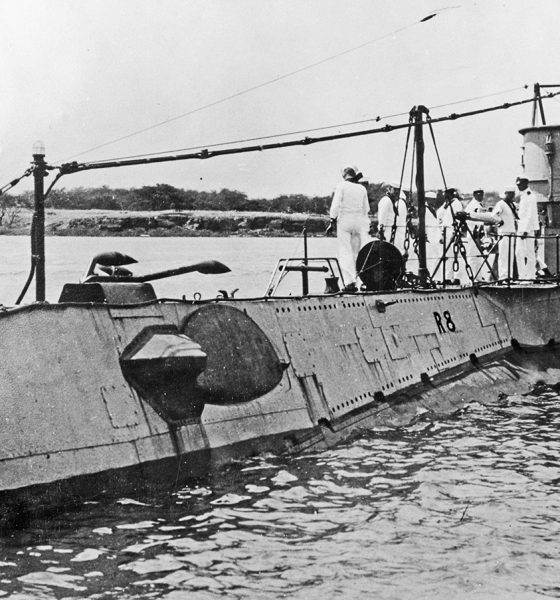

A year or so later, Green gave the Olinda Wreck location to Joe Mazraani. In December of 2020, when Mazraani side-scanned the Olinda Wreck, he found that the wreck was not a freighter but a submarine, which he identified as the R-8. The R-8 had been scuttled in a bombing test in 1936. Except for a photograph in my R-8 folder, the only information I had were its historical location and depth: some 113 km/70 miles from the Olinda Wreck, at a depth of 1,317 m/4,320 ft.

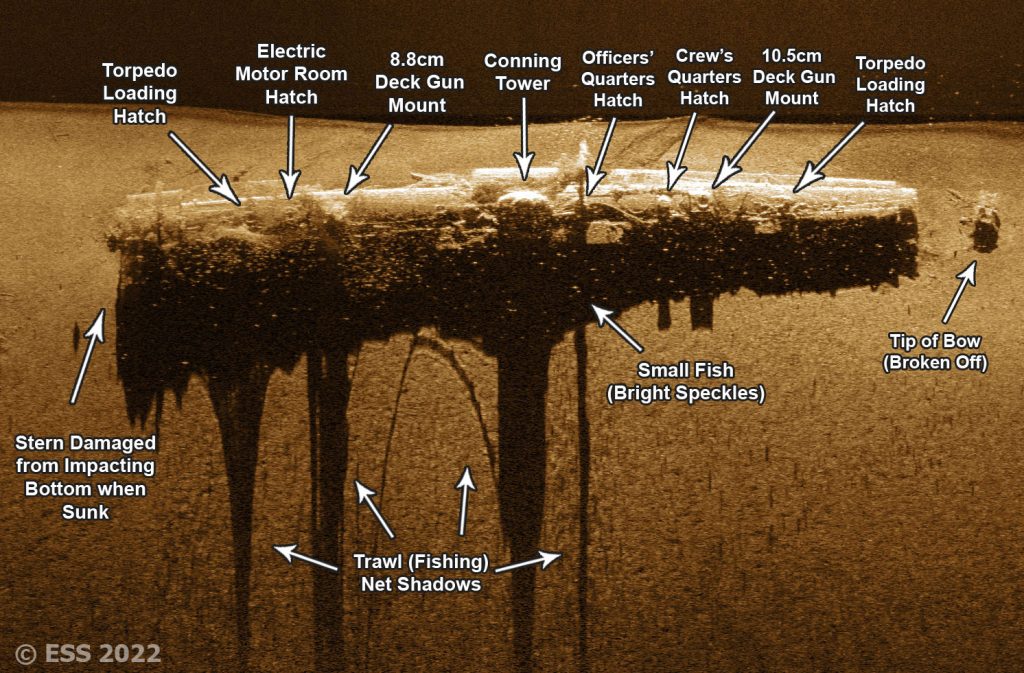

Mazraani issued a press release including the side-scan sonar image. The conning tower in the scan did not look like the conning tower of the R-8. I pulled Shipwrecks of Virginia off the shelf and turned to the chapter about the U-111. The book had two photos of the U-111 and its conning tower. The conning tower in those photos matched the size and shape of the conning tower in the side-scan sonar image, and did not match the size and shape of the conning tower of the R-8. At that moment, I was certain that the Olinda Wreck was the U-111. And I remained fully confident in that conclusion.

However, no one believed me. For a year, I stood alone in my never-shaken confidence. Then it took another six months to obtain absolute proof—a year and a half in all.

Divers who had no background knowledge of the U-111 would not accept the results of my research. To them, yet another U-boat coming to light seemed preposterous. So little faith did Ben Roberts have in my conclusion that he decided not to side-scan the Olinda Wreck during his 2021 wreck survey, when he side-scanned 191 other wrecks! (See his website at Eastern Search & Survey)

Yet, not only was Roberts the first one to side with me after he corroborated my original research, but he also took matters in hand by convincing Ross Baxter to explore the wreck with his remotely operated vehicle and video camera. I must also mention those who subsidized the cost of chartering a boat by each donating $375 to the cause: John Copeland, Jon Haws, Michael Haws, Dan Quinlan, and Jim Walsh. I thank them all for the faith that they had in me and my promise to expose yet another lost U-boat to the world.

The confirmation dive took place on June 22, 2022. Afterward, Ben Roberts took his boat to the site and obtained high resolution side-scan images of the U-111. He annotated one image to show the most prominent features of the wreck.

As the saying goes: the rest is history.

This concise introduction to the emergence of the U-111 is told with greater detail in U-111 Exposed. The 240-page book provides information about the Billy Mitchell Wreck Project, focusing on the discovery of the other three U-boats. The book is illustrated with 90 photographs of the U-111, many of them showing the interior, plus another 82 black and white photos and 39 color photos. The book is available now.

DIVE DEEPER

The rest of the U-111 story from the U-111 Team: U-111 Teamwork, Technology and Wreck Identification by Rusty Cassway

The Rest of the story from the U-111 Team: U-111 Teamwork, Technology and Wreck Identification by Rusty Cassway

InDEPTH: For Whom The Shipwreck Bell Tolls by Gary Gentile

TDI|SDI aquaCORPS Archives: GARY GENTILE: DEEP WRECK DIVER (JAN 1991)

ScubaBoard: Neox, Argox, Ken Clayton & Billy Mitchell Fleet talk Our World Underwater Chicago (FEB 2017)

Gary Gentile Productions: The U-111 Exposed

Gary Gentile, author, lecturer, photographer, explorer, and deep-sea wreck-diver, has written 68 books—including one of the first on technical diving—published more than 4,000 photographs, and discovered more than 40 shipwrecks. He was the first scuba diver to enter the First Class Dining Room of the Andrea Doria, and he recovered a number of Italian artist Romano Rui’s ceramic panels that once adorned the walls of the First Class Bar.

In the early 1990s, he was instrumental in merging mixed-gas diving technology with wreck diving. His dive to the German battleship Ostfriesland, which lies at a depth of 116 m/380 ft, triggered an expansion in the exploration of deep-water shipwrecks and the advent of helium mixes.

Gary specializes in wreck diving and shipwreck research, concentrating his efforts on wrecks along the eastern seaboard from Newfoundland to Key West and in the Great Lakes. Over the years, he has recovered many thousands of shipwreck artifacts. He has preserved and restored these relics from the deep and displayed them at various museums, symposiums, and exhibitions.