Exploration

The Devil In Your Dive: My 70-km Traverse of the St. Lawrence River

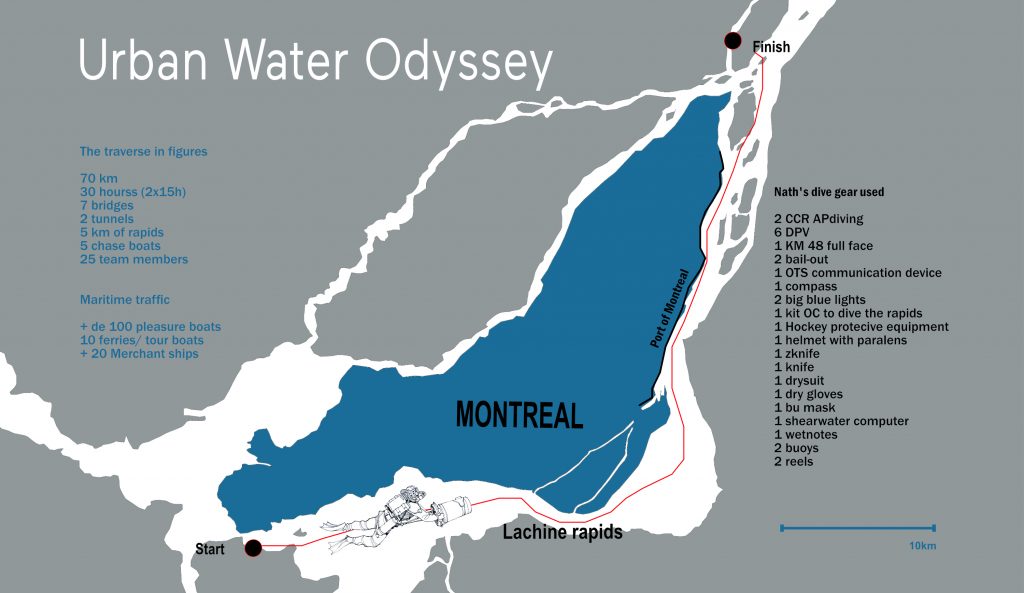

Award-winning filmmaker, explorer and tech instructor Nathalie Lasselin spent 30 hours underwater braving a 70-kilometer stretch of the St Lawrence River surrounding Montreal, in the interest of water conservation—the river supplies 80% of Montreal’s drinking water and 50% of Quebec’s. How do you prepare for a scooter dive that includes drinking, eating, and sleeping underwater, while avoiding becoming Seadoo fodder? Nath tells all.

by Nathalie Lasselin

Images courtesy of N. Lasselin

You must have heard that idiom: “The devil is in the details.”

If there is a god for the divers, trust me there is a devil as well.

Let me tell you how I met him.

Everything started years ago, when I began to ask myself a recurrent question. I live in Montreal, and each time I come back home by plane, we fly over the St Lawrence river, and I couldn’t stop asking myself: What would it be like to traverse the entire island of Montreal in that river? If you take a closer look at the St Lawrence from up there, you will see a dark, greenish-brownish body of water flowing with rapids in different sections, being spanned by seven bridges, and containing lots of heavy ship traffic going to the great lakes.

But still, I had to see it with my own eyes, to feel it with my own body! A dive so different from all my past experiences, having dived deeper than 110 meters in caves, in strong currents, in nearly no visibility, filming wrecks, and in the freezing water of the Canadian Arctic. I’d had years of training, teaching, exploring, and had always questioned the best way to do things (meaning the most suitable way to achieve my goals) And now I wanted to check it out, I had to try it. I had to do a lengthy, 70-kilometer/44-mile traverse in an impetuous river. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. It looked insane and not sexy at all for a dive plan, but my options were to attempt it, or to one day become an old woman and regret that I hadn’t at least tried. Regret seemed worse.

I started the preparation for my Urban Water Odyssey: The 70-km scuba diving traverse of the Saint Lawrence River from one end of the island of Montreal to the other, knowing I had to be obsessively meticulous about all the little details in the preparation for the dive on many different levels. There would be equipment, logistics, team, training, environment, a dive plan, mindset, as well as mental, physical, and psychological preparation. I was headed for a different kind of dive, one that would involve more than 30 hours of immersion in the water.

So where to start? There was no guidebook, no written instructions for a dive like that. The challenge: A 70-kilometer obstacle course with a total time of more or less 30 hours in water, in rapids, strong currents, in low visibility, with structures—including ships and other hurdles such as big rocks—to avoid.

People didn’t understand why this project was so important to me. I explained that one of the most important reasons for my passionate curiosity about this magnificent river had to do with the fact that the St Lawrence river is the source of drinking water for 80% of Montreal and 50% for the population of Quebec. We humans cannot live without water for more than three to five days, and we tend to take it for granted that clean water will flow when we simply turn on our taps. This alone was enough motivation for me to pursue my ambitious plan.

In addition to the dive, I also wanted to collect water samples from the river, and planned to do so every 15 km/9.3 mi in the countryside and every 4 km/2.5mi in the city over a 350 km/217.5mi distance. My hopes for these samples was to determine how many and what kind of contaminants were present. The analysis would be handled by the chemistry department at the University of Montreal. As an underwater explorer, I felt privileged to be able to witness this environment first hand, and felt the need to do whatever I could to protect this most critical source for all life and make the public aware of the situation.

Preparing To Make The Dive

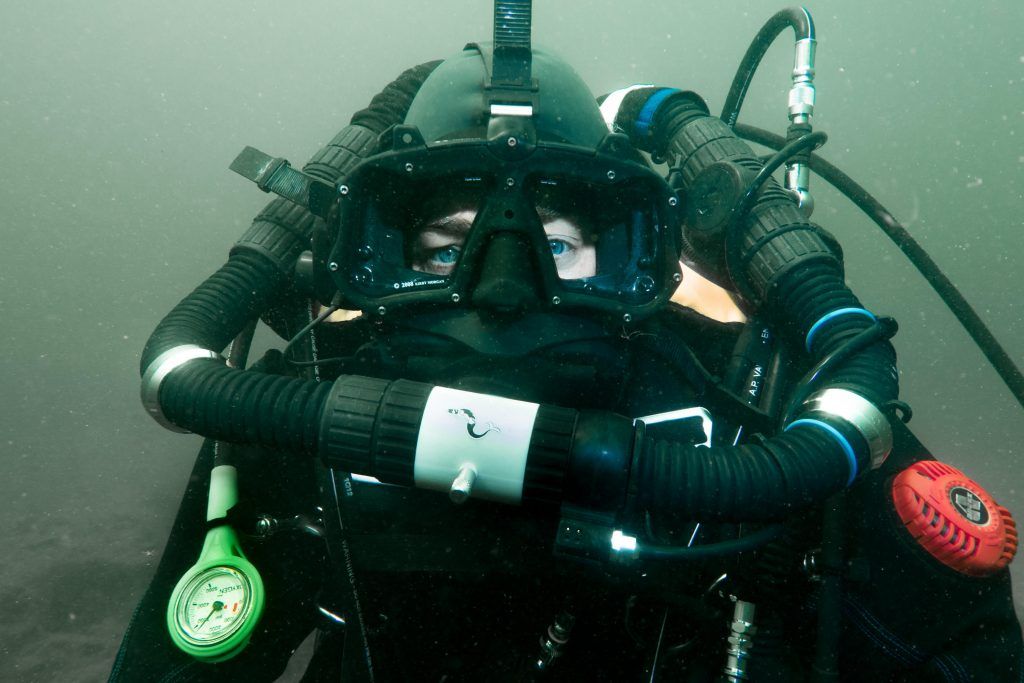

Going back to the basics, physically I needed to be on the top of my game and be fit for the dive, and I had to train differently to have a perfect core. In order to do the dive safely, I would be towed by a DPV in one direction with a surface marker buoy attached to me that was going to pull me in the opposite direction. My team had to know at all times where I was in order to give me an azimuth to follow so I would stay on my path. Anyone who had ever done a couple of hours of DPV with a CCR, bailouts, and some extra equipment, would understand easily how the pain slowly makes its home in your body.

Of course, even if the water was around 20ºC/68ºF, after hours of immersion, cold could be an extra challenge, and I would have to eat and drink underwater to keep my energy. I trained to use a Kirby Morgan M-48 MOD-1 full face mask. My only option to go from OC to CCR, in order to have communication, would be to remove the mouthpiece part to eat and drink at the same time, as my safety diver would be keeping an eye on me. So I trained myself to be able to eat, drink and even sleep underwater using auto-hypnosis.

More on Nath’s training: [popup_anything id=”8072″]

Mentally, I had to be prepared to face doubt, adversity, fatigue, and pain. I had to trust in the dive plan and my safety team. My motto, once I was in the water, would be that I had one job to do: go from A to B. The rest would not be in my hands anymore.

To complete the picture, the logistics was undoubtedly the most time- consuming and delicate task when faced with the unknown. With a constrained budget, I had to figure out so many aspects to follow: the divers had to be trained to help me replace equipment underwater, to take samples for the scientific aspect of the mission, to obtain all the required pieces of equipment for the dive itself, and finally to put together three independent surface teams to relay with each other at specific points with five different boats. No one boat could follow the entire dive because of the nature of the river.

Over the months of planning, I gathered tons of equipment with the help of partners, manufacturers, and individuals in order to have the famous redundancy for every single item, from different pairs of fins in case it hurt too much on the arch of my feet, to back up CCR, and DPV. I decided to do the entire dive with my AP Diving Evolution CCR except for the 5 km of rapids that I would do on open circuit.

Nearly one-third of the dive is in non-navigable waters. The marine map is just white, no data, which means shallows, insane current, and numerous hazards. In that portion, I would face currents from every direction and intensity, as well as currents that were too strong to fight. Basically the river would beat me up and make me do loops and turn 360 in every direction. So for the rapids, being light on OC seemed to be my best option, which went nearly perfectly.

Asking the Right Questions

Here some tips about how to ask the right questions. When preparing a dive—an expedition—we are not just divers anymore. At the end of the day, diving may be the easiest part, since we have the training, the skills, the equipment, the redundancy, and our regular dive buddy. But before, after, and during the dive, we are a traveler, a potential first emergency responder, a cook, a boat captain or passenger, and a guide. And, we might face adversity we had never encountered before with people in our group that we never worked with during a high stress situation. What we can do to make sure:

- We agree on our what-if solutions

- We know and are ready for our dive plan

- We prepared our dive trip to perfection

- We have a harmonious, collaborative, and fun group of people who all agree on their roles and positions, on their strengths and weaknesses, without judgment.

With all these components, what is funny is that to a certain extent we do have control over them, and that may be why it is easier to list them, plan them and think about them. So if we do your job, a decent one at least, we should be all good to go for our next challenging or adventurous dive.

We took some time with the teams to train the divers and I told each of them, don’t trust yourself, don’t trust me, I may make mistakes. So everything should be double-checked and logged in the “Project Bible’’. As it got closer to D-Day, I asked myself what it was that I hadn’t thought of. I wondered what it was that would be obvious afterwards.

D-Day At Last

My dive started Friday September 14, early in the morning. At that time of the year in Montreal, mornings were usually filled with fresh humidity, and temperatures didn’t rise much. Except that day!

One could think, “Well that was good news for the team on the safety boats. They would just drink less coffee or hot chocolate to keep them warm.” Nobody could be against a warm, sunny day on the river, right? Nobody except me. Because of that amazing, warm temperature, every single person who could take a day off from the office and who had a boat was on the river. Even if the river is pretty wide in Montreal, there is not a lot of water. The deepest part is in the seaway channels that need to be dredged.

Sharing the rivers between marine traffic, pleasure boating, seadoo, kayakers, and stand-up paddle boards was not a good mix. Adding a diver into the equation, knowing that most of the people did not understand what a dive flag was, did not bode well for my project.

So guess what my beautiful path on paper and waypoints on the GPS became in a couple of hours? Nearly useless. Sharing the rivers between marine traffic, pleasure boating, seadoo, kayakers, and stand up paddle boards was not a good mix. Adding a diver into the equation, knowing that most of the people did not understand what a dive flag was, did not bode well for my project.

Finally I ended scootering with the shallows. In the St Lawrence river, like in many other bodies of water nowadays, invasive plants are taking all the sun and warmth of the water to grow up to the surface. In a matter of hours, I had transformed myself into an underwater lawn mower, overusing the batteries of the scooters and having to clean the props way too often.

Nath’s harrowing incident: [popup_anything id=”8077″]

That little warmer weather detail had a huge impact on the entire project. What was supposed to take me an hour, based on all the proof of concept dives, took me twice, triple the time. I did all I could do not to stop, to go in the straightest line possible with my divers giving me a fresh DPV, a syringe of avocado or some high protein soup in a soft bottle.

We worked all together with the first team that was supposed to be out of duty around 1 PM. Instead, by 10 PM, my dive supervisor said, “Either we pull the plug and you try it another time next year, or you agree to get out of the water and wait until sunrise to keep going.” It was true that I couldn’t cross the rapids in the dark. It was too dangerous and the supervisors knew they couldn’t guarantee the safety of not only me, but the entire support team, so they called the dive for that day.

It was my own dear project. A project that couldn’t be completed without a support team, and in circumstances so much more different than any other dive. The entire team of 25 persons involved agreed to stay with me no matter how long it took.

The next morning at sunrise, I dove back in the river for another 15 hours. The challenge was not easier on this day because marine traffic was even more intense than the first day. Being in low visibility, low contrast, for a very long period of time, with fatigue, I started to experience the Charles Bonnet syndrome. Basically I saw things—colors, shapes that did not exist. At first I was surprised and then amused by what I saw as free entertainment to help me complete what was a monotonous scooter dive with not even five feet of visibility. My body was exhausted, my vision was impaired, but my mind was all there, so happy to imagine the point B.

By Saturday at 10 PM, 12 hours after the planned ETA, I finally arrived at the finish line with the support of all my team. After the dive, it took me a couple of days to get back to a normal level of energy without any injury. The dive gave me the media visibility to talk about the adventure, to describe the team work, and to explain about the importance of the river as the source of our drinking water.

My second piece of advice: No matter if it is a small dive or a big adventure, prepare for it the best way you can, with reminders and lists. Practice your skills with well-maintained equipment. By keeping an open mind, a close team working toward the same goal, with the humility and the flexibility to switch to the safest back-up plan, your adventure might be a different one, but still will be the most rewarding one, and the dream of one individual may become larger than themselves, “plus grand que la nature.”

Dive Deeper

Nathalie Lasselin’s Urban Water Odyssey Facebook Page

Discovery Channel: Nathalie Lasselin prepares for her traverse through the St. Lawrence River.

Nathalie Lasselin is an award-winning filmmaker and producer. She trained at the National Film Board of Canada and is an arctic dive expedition leader, CCR, cave and wreck explorer and instructor. As an international speaker, a writer, and on-camera talent/technical dive specialist for TV shows, she shares her passion for discovery in a challenging environment. For the past years with her project, Urban Water Odyssey, diving the 70 km/44 mile long shore of Montréal, she brings people together to raise awareness and better action towards the preservation of fresh water. She is also a Women Divers Hall of Fame (WDHOF) inductee, Royal Canadian Geographic Society (RCGS) member, and a member of The Explorer’s Club.