Community

The Call of the Wah-Wah

The lingering legacy of DEEP AIR in the era of MIX—from the aquaCORPS archives

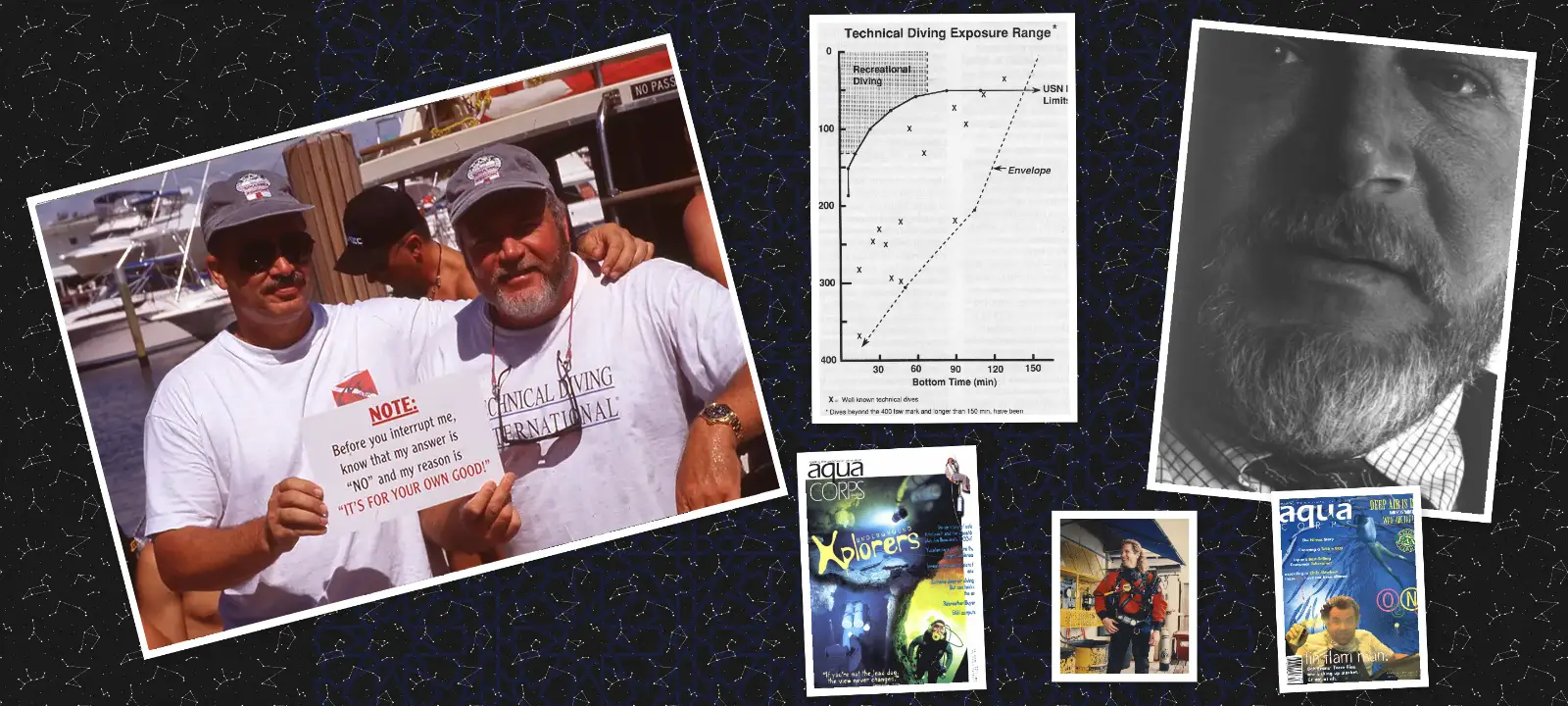

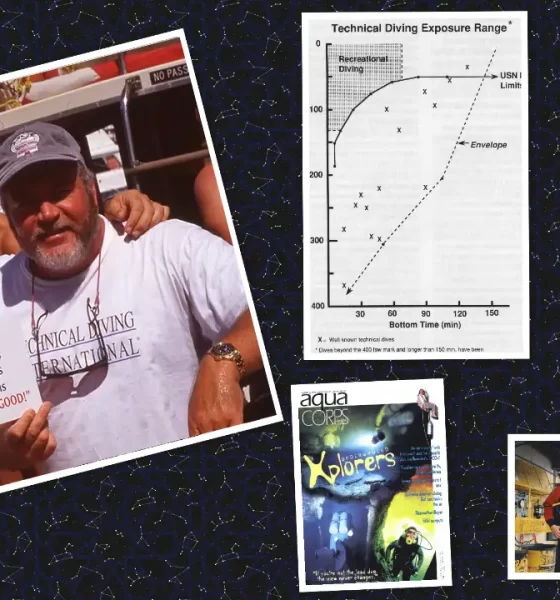

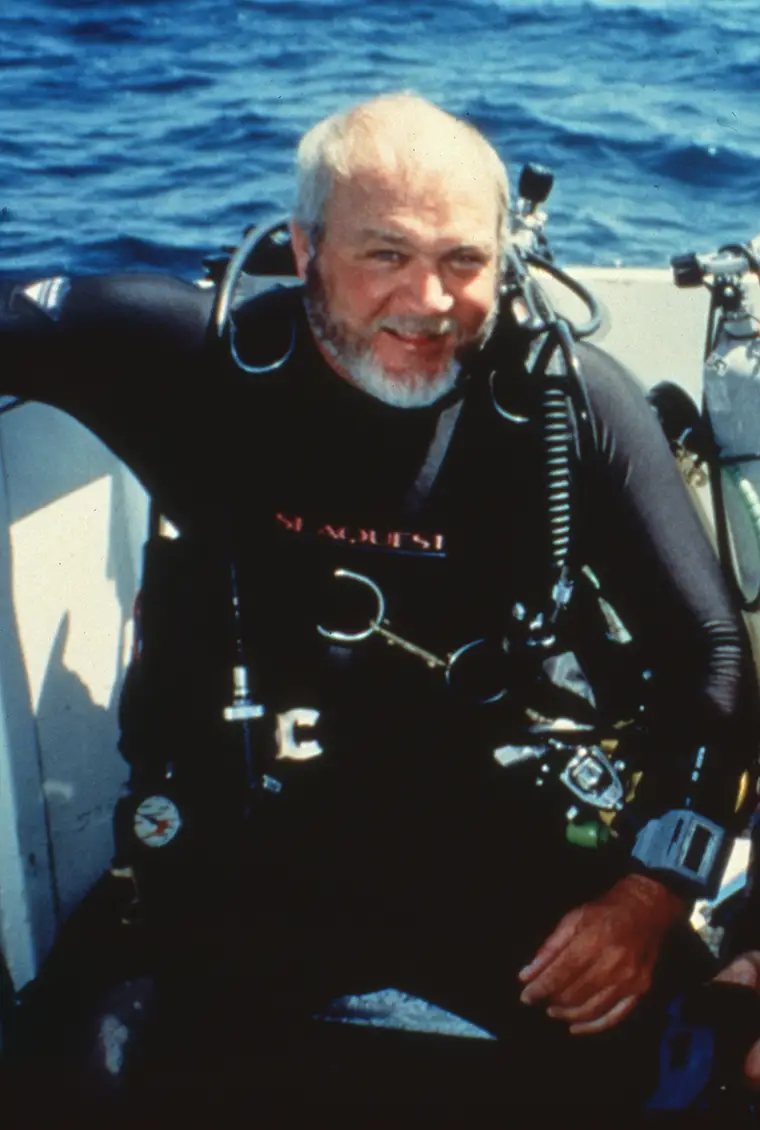

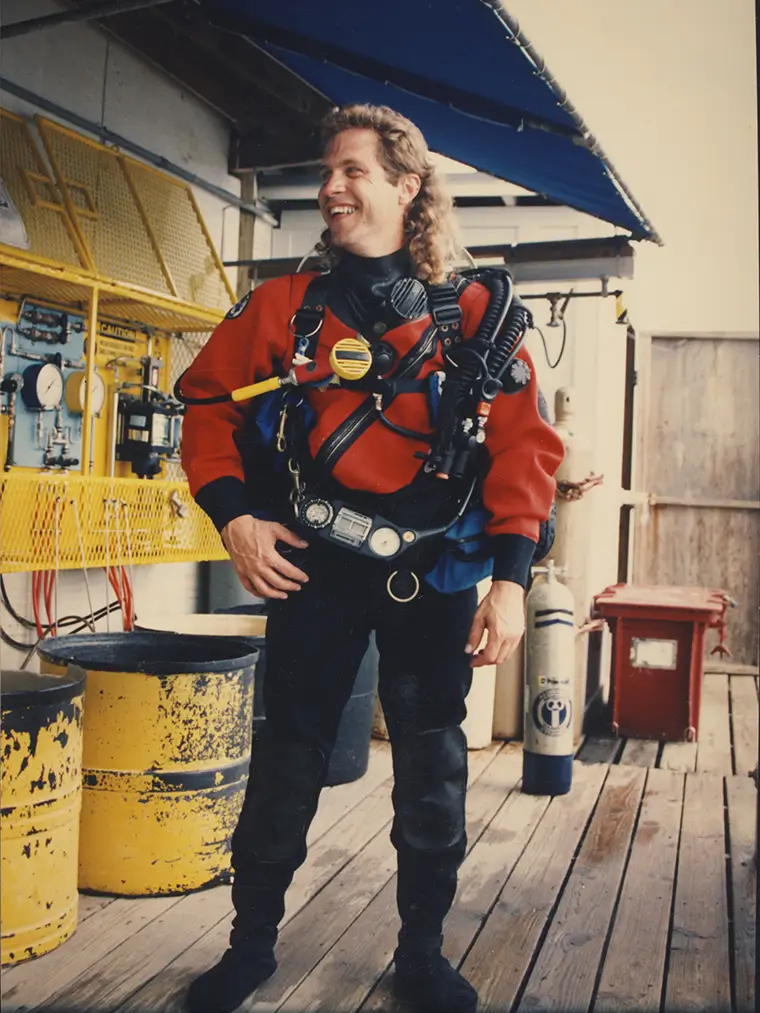

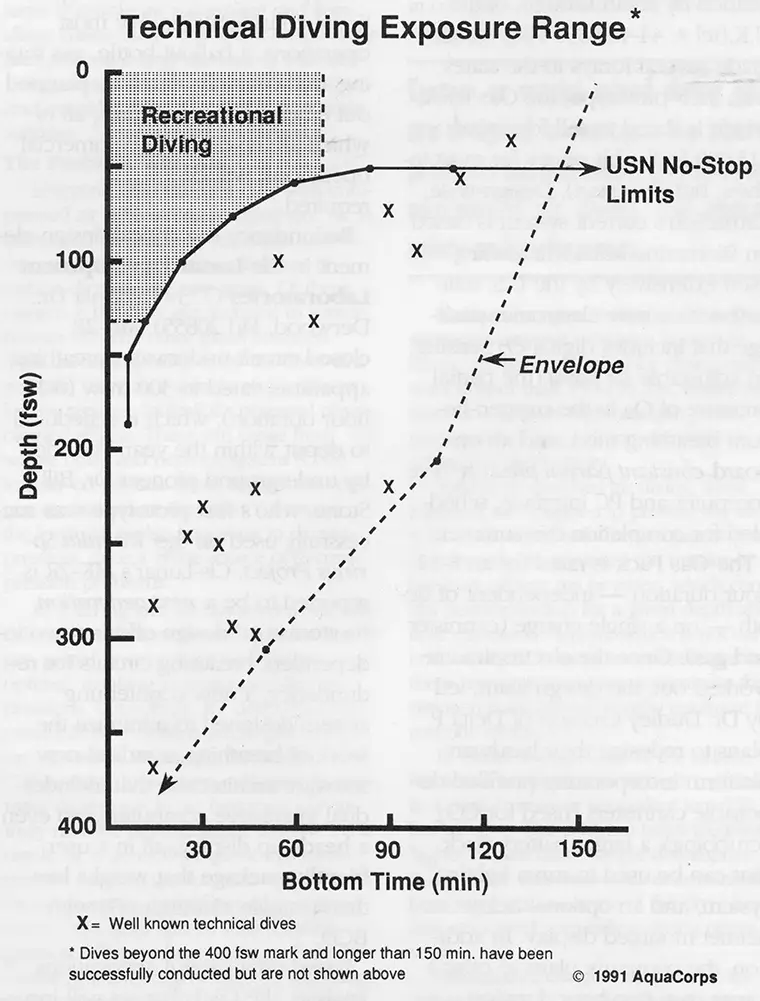

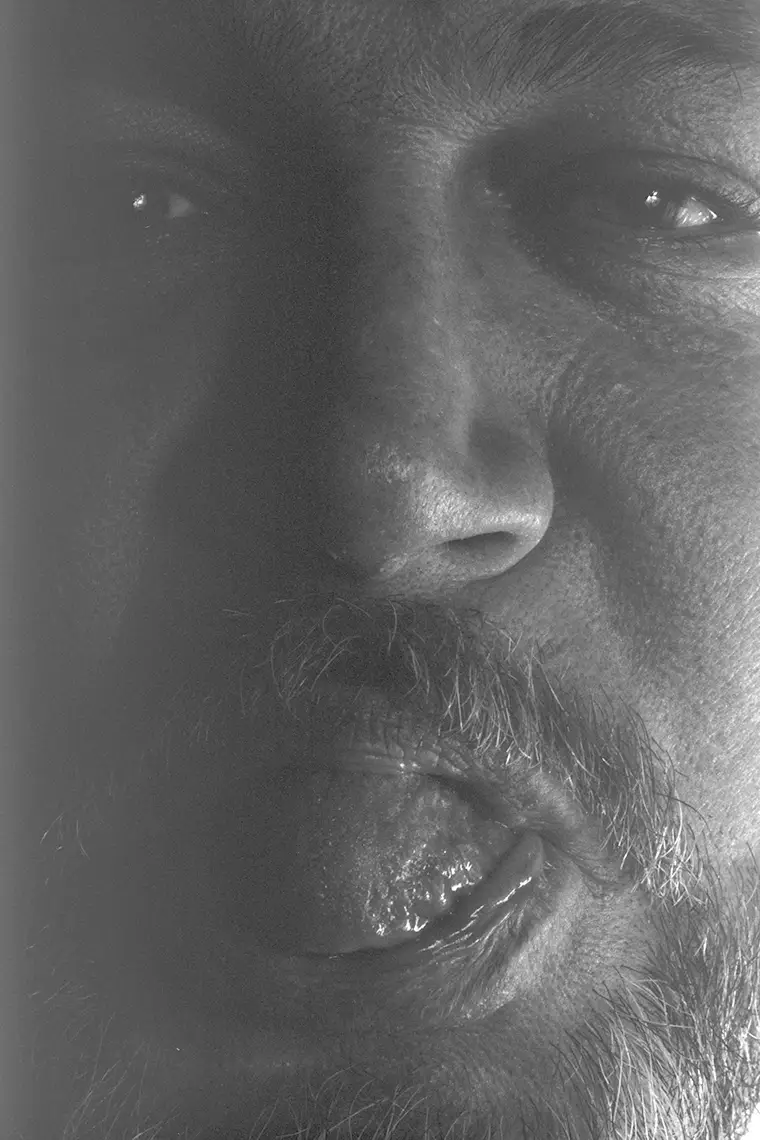

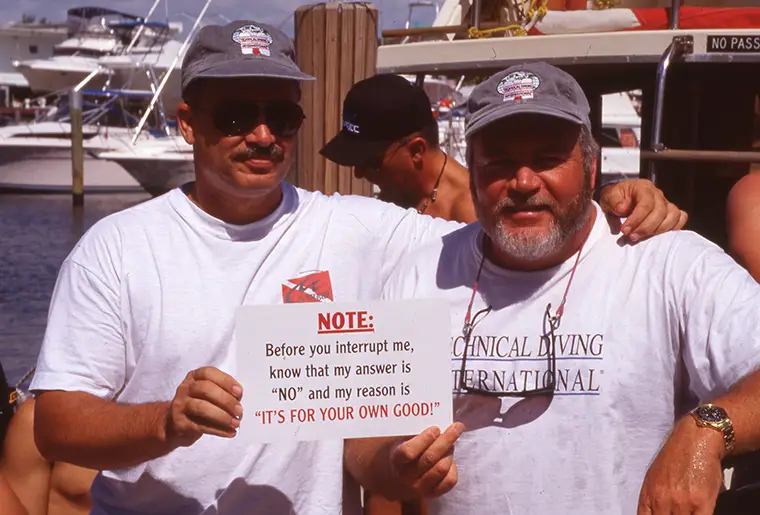

Republished from aquaCORPS #11 XPLORERS (1995) and aquaCORPS #13 O2N2 (1996). Lead images: L: Joe Odom and Bret Gilliam showing attitude. Ctr: aquaCORPS’ Tech Diving Exposure Range, R: Bret Gilliam. Images courtesy of the aquaCORPS archives unless noted.

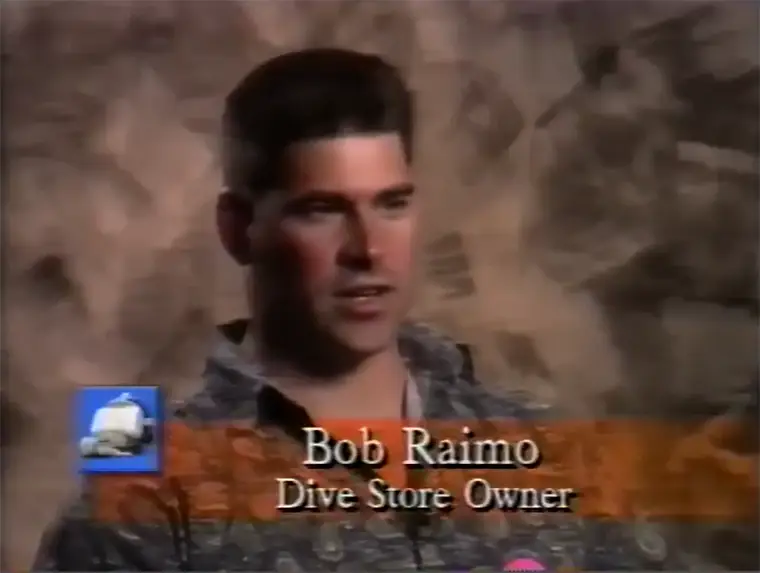

As I was going up, passing 325 feet, I heard this noise—wah-wah-wah-wah—really loud. It really scared me. I didn’t know what it was. I could not see my hand on the cable. All I could see was my gauge. Everything else was black. Joe Odom says when you hear that noise, you’ve been fucked up on air, you’ve been deep on air. It’s called the “wah-wah.” — Bob Raimo

In the early days of tech diving, the onus was on the community to demonstrate that we were responsible divers and not cowboys, wild and crazies, as many believed. So, imagine my dismay at aquaCORPS when we learned that Technical Diving International (TDI) co-founder and president Bret Gilliam and NSS-CDS chair Joe Odom were conducting 122m/400 ft bounce dives on air using single aluminum 80s, during a TDI Dräger rebreather instructor course in the Bahamas. It was July 1995. We thought deep air diving was dead!

In fact, one of the instructors present at the course, Bob Raimo, nearly lost his life during one of the deep air dives, which is how we were alerted to the story. My managing editor Dean Mullaney interviewed Gilliam, and we published the story in aquaCORPS #11 XPLORERS, August 1995, along with an interview with Raimo, and my response as aquaCORPS chief. Gilliam subsequently threatened to sue aquaCORPS following the article unless we issued an apology and gave TDI four full-page color ads in the magazine. I declined. Instead we offered Gilliam and Odom an opportunity to tell their side of the story in a subsequent issue, aquaCORPS #13 O2N2, January, 1996. With all due respect to the individuals cited in this story—Rest in Peace Bret and Joe— here then is “The Call of the Wah-Wah” as it ran in aquaCORPS Journal in 1995/96.—M2

P.S. TDI Trimix and rebreather Instructor Rob Palmer who attended the Bahamas workshop sadly lost his life on a 120 m deep air dive in the Red Sea two years later.

The stories as they appeared in aquaCORPS:

The Call of the Wah-Wah

by Dean Mullaney

I Heard the Wah-Wah

As told to aquaCORPS by Bob Raimo

Calling a Wah a Wah

by Michael Menduno

A Word from The Wahs

by Bret Gilliam and Joe Odom

FREE aquaCORPS DOWNLOADS Below

The Call of the Wah-Wah

By Dean Mullaney. Images courtesy of the aquaCORPS archives unless noted.

A handful of leading training agency officials and instructors conducted deep air dives, some exceeding 400 ft/123 m on non-redundant single aluminum 80 cf cylinders, raising serious questions about the dichotomy of individual freedom versus instructor responsibility.

The stunts, as some have called them, occurred at Drager/UWATEC’s first formal rebreather training seminar in the Bahamas 9 to 14 July 1995, with over a dozen Technical Diving International (TDI) instructors present. TDI president Bret Gilliam and NSS-CDS Chairman Joe Odom led the dives, and each used single 80 cf cylinders, and had no redundancy.

While all divers survived the experience, New York-based TDI instructor Bob Raimo, who carried an 80 cf stage as a back-up, nearly died on his second dive beyond 300 ft/92 m. The participants tried to keep the dives secret, both at the seminar and afterwards.

THE REACTION

Reports of the clandestine dives spread like a wildfire among tech divers and provoked a plethora of questions. Why make a deep air dive in the first place when no useful work can be performed at depth and when mix is available? Why risk diving without a redundant system? How can tech diving instructors teach their students to stay within limits yet exceed those limits themselves? What responsibility do these industry leaders have to send the right message to their followers?

Many leading figures in the field privately condemned the stunts but were reluctant to comment publicly. However, reaction in general to the practice of deep air diving beyond 400 ft/123 m without a redundant system was strong and one-sided.

“You wouldn’t catch me doing that,” said training instructor Lamar Hires, Joe Odom’s associate at the NSS-CDS. Hal Watts of the Professional Scuba Association (PSA), who trains divers on deep air, said, “Our training standards don’t permit it. If you’re making deep dives, we require enough gas for the dive plus extra gas on the descent lines in case of emergencies. People do it, it’s okay, but we have to consider, ‘What if?’”

Les Joiner of Ocean Corporation said, “We had to deal with the problem of cowboys in commercial diving twenty years ago.” Another leading tech diving expert, who asked not to be identified, declared, “Natural selection is a slow process.”

The consensus on limits and acceptable practices for diving on air is near universal. The maximum operating depth for air is between 180 ft/55 m and 220 ft/68 m, based on a working PO2 between 1.4 atm and 1.6 atm. As President of TDI, Bret Gilliam ironically said, “I have yet to see anybody that’s got any degree of credibility stand up and say, ‘It’s okay to go to 300 feet on air.’ That’d be absolutely, bloody stupid.”

Field experience suggests that maintaining PO2s below 1.4 and 1.5 atm during the working phase of the dive is optimal, allowing for oxygen levels to a maximum of 1.6 atm during resting decompression.

Experts further agree that it is prudent to have an appropriately redundant breathing system—minimally first and second stage redundancy—when diving in open water beyond about 60 ft/18 m. In extremely deep dives and in an overhead environment, it is a requirement. Like the rule of thirds, redundancy is a defining tenet of tech diving.

THE INCIDENT

The dive originated with Gilliam and Odom. Says Gilliam, “Odom and I do a lot of deep air diving and we had the opportunity on a really unique wall. The only thing available was a couple of eighties. But the breathing rate that Odom and I have is so remarkably low compared to everyone else. We did a dive to 441 ft/135 m and we used about 1,100 psi of gas.”

The pair agreed to keep all divers, including some who were using trimix, above them at all times. “We didn’t want them to get away from us… We were a hundred feet or more deeper than the guys on trimix. And used half, maybe a third of the gas they did.”

The other participants—who included Mitch Skaggs and Jesse Armantrout, as well as Bob Raimo—said that they were not pressured in any way and only attempted the deep air dives because they were in the company of top industry professionals such as Gilliam and Odom. “Joe did not go around the boat, ‘Hey, we’re going to do some deep diving. Who’s interested?”’ said Raimo. “It was a very private conversation.”

Gilliam rationalizes the dives by boasting of his conservative gas consumption. “I breathe half of the gas volume that other people do that are half my size and half my age,” said Gilliam. “I can’t explain that. Part of it is being relaxed in the water, getting into some kind of rhythm that works for you, but I see a lot of these other people that are hopelessly overburdened with equipment that they don’t seem to realize what it does to their performance in the water. Odom and I spent quite a bit of time down there between 375 and 400 ft/115 and 122 m and change. We had time to stop and smell the roses. It’s no big deal to us. We were kinda surprised when we came back up that everybody was making such a big thing about it.”

Gilliam is not concerned about oxygen on deep dives like this and cited that divers push 3 atms of oxygen in the chamber as a matter of routine. He also said that, at rest, the chances of an oxygen toxicity problem in a relatively short duration are minimal—and more friendly than decompression.

Yet the accepted standards are not malleable, said an industry insider. “The 1.45 atm limit is not there for everyone except Bret Gilliam and Joe Odom,” he said. “The limit is there for all divers.”

Gilliam believes that experience and understanding of the risks are what counts. “I’ve been doing this for twenty years,” he said. “I have never, ever had even the slightest symptoms of O2 problems, and I don’t expect that I will. But I have also made a career of understanding the underlyng physiology to the point where, believe me, every hair and follicle is tuned to the expectation that I’m going to have a problem.”

Diving so deep without a redundant system seems to be a non-issue with the pair. “Both of us were diving thirds,” said Odom. “From a rules standpoint, hell, we’re diving thirds. Anybody got a problem with diving thirds? I mean, shit, leave me alone. What does an 80 have to do with it? We had air, we went down; we had air, we came up.”

Bob Raimo opted for redundancy. “I was very uncomfortable diving with single 80s, so I jerry-rigged some telephone wire to an 80 stage bottle,” he said. “I wanted to at least have a back-up bottle… This single 80 stuff—boy, you have one regulator failure… It’s not like getting a flat on the highway. You don’t have a spare.”

RISK ACCEPTANCE

The practice of deep air diving has fallen in and out of public favor over the years. Today, with the availability of mixed gas, extreme deep air diving is again in dispute and is generally considered unnecessary and dangerous.

“In the old days, you had to be in the closet,” Joe Odom said, “because you didn’t want anybody to know about it. Then deep air was accepted. Now we have to go back into the closet a little. Because of [mixed] gases, people are chastising the deep air people, saying you don’t need to do that.”

“In the old days, you had to be in the closet,” Joe Odom said, “because you didn’t want anybody to know about it. Then deep air was accepted. Now we have to go back into the closet a little. Because of [mixed] gases, people are chastising the deep air people, saying you don’t need to do that.”

Hal Watts, whose training divers to 300 ft/92 m is also controversial, is quick to point out that a dive beyond 300—particularly one below 400 ft—is beyond the safety limits on air.

However, divers continue to dive deep on air, and a small number attempt the questionable practice of setting deep air “records.” A 27-year-old diver training to exceed Dan Manion’s air dive to 513 ft/158 m—the deepest recorded at the time—recently died off the coast of Ft. Lauderdale [See: Examining Early Technical Diving Deaths: The aquaCORPS Incident Reports (1992-1996), June 1995, Offshore Broward County, Florida]

Reportedly, members of the tech diving community—including Gilliam, Mitch Skaggs, and lANTD’s Tom Mount—discouraged the young diver from attempting the depth. “You can talk about the sanity of solo diving,” said Joe Odom. “But it all comes down to risk acceptance. How can we train the new guys for emergencies? We can’t. The fact remains that some of us have survived incidents that we shouldn’t have survived. And we’ve got very strong survival instincts as a result.”

Gilliam says of inexperienced divers who go beyond their limit: “Unfortunately, it’s nobody’s fault but their own. If you look back six years ago, there was no aquaCORPS, there was no Watersport publishing library…the only way you could get information was if you were in somebody’s clique. Now there’s this whole explosion of information out there.”

Odom has a theory about younger divers. “We have a whole generation of techno-babies—and I use that in a semi-derogatory form—that are diving,” he said. “These are the people who sit in front of their computer and are able to hit a carriage return and get instant gratification. We’ve got people who believe they can sit in front of a computer terminal and learn how to become a deep air diver. They don’t even know what they feel yet. That’s what years of diving are about.”

Bob Raimo, who is an experienced mix diver but who had little deep air exposure, said that he learned more on this one— almost fatal—dive than he had on a hundred other dives. “I’ve taken my experience and learned this from it,” he said. “You don’t dive deep on air. There’s mix. I can teach people that from experience now. I can tell them, ‘Look, I got lucky, and luck is never part of my dive plan.’”

Even with his near-death experience, Raimo won’t rule out diving deep on air again. “I’m not going to tell you that I’ll never do it again because the experience has not scared the thrill out of me in diving,” he said. “However, if I want to be a respected figurehead in the technical community, then I can’t do deep air diving. So, from that point of view, my answer is no.”

“It was a scary learning experience that I wish never to happen to me or anybody else again,” he added. “I can say this, if I ever decide to do a deep air dive like that again, I’ll be ready for it. I’ve been there. I’ve heard the wah-wah.”

INDIVIDUALS VERSUS RESPONSIBILITY

Few people dispute each individual’s right to dive as they please. The libertarian streak among divers is profound. There is, on the other hand, a deep division in the tech diving community about whether leaders have an added responsibility and if they are sending the wrong signal to less experienced divers. The debate over the Tapson-led Lusitania expedition [see aquaCORPS #10 lMAGING] symbolizes this colloquy—although, in the Lusey situation, the participants were not training instructors.

Where do technical divers draw the line between individual freedom and collective responsibility?

Lamar Hires of the NSS-CDS summed up the conundrum: “It’s a gray area and one that we always come back and fight with.”

Hall Watts, however, is definite in his opinion. “Everyone should follow safety guidelines, whether they’re leaders in the industry or John Q. Diver,” he said. “It’s ‘Monkey see, monkey do.’ Leaders should do things more safely to set an example.”

“Everyone should follow safety guidelines, whether they’re leaders in the industry or John Q. Diver. It’s ‘Monkey see, monkey do. Leaders should do things more safely to set an example.”—Hal Watts

Bob Raimo acknowledged the problem. “We’re clearly not practicing what we preach. And I have mixed feelings about that,” he said. “I’ve always been an adventurous individual—which is why I like diving—and I like to satisfy that thrill, that sense of adventure. And I think for a lot of people, diving deep on air is that sense of adventure, that thrill. Yes, there’s a grave risk, but if one is willing to accept that risk, then one should be allowed to do that. But if people want to be figureheads and leaders in this business, they need to be promoting the right thing. The problem is, do we take away someone’s individuality, the right to do something stupid? And I don’t know.”

Joe Odom addressed the dilemma in a somewhat different manner. “The fact that some people want to go beyond 1.6 [PO2] is their personal choice,” he said. “But I don’t think anybody in good conscience will train [someone] to go beyond 1.6 unless there’s medical evidence to suggest otherwise. Are we creating a climate of ‘Do as I say, not as I do?’ Well, of course, but that’s the way it’s been since day one.”

“Are we creating a climate of ‘Do as I say, not as I do?’ Well, of course, but that’s the way it’s been since day one.”—Joe Odom

Odom, who is also a flight instructor, likens himself to a test pilot. “Everybody thinks they’re reckless daredevils,” he said, “and that’s not the case. They have a program of pushing the envelope a little bit each time, analyzing the data, and saying, ‘The next time, this is what we’ll do.’ Only until you’re comfortable within that range can you—with any degree of intelligence—go forward.” Gilliam believes that his experience will benefit others. “Since I’m using 70% less gas and carrying 70% less gas than you are, you might at least want to learn something from it,” he said. “Experience is a word everybody ought to look up in the dictionary.

You don’t get it simply by sewing patches on your fuckin’ dive jacket. You gotta go out there and get wet. We’re doing things with half the effort and half the gear that some of the other fellows are doing, and it’s not that we’re any better divers. I think that it’s just that we’re a little bit smarter and can apply lessons learned over the years of experience.”

“You don’t get experience simply by sewing patches on your fuckin’ dive jacket.”—Bret Gilliam

THE PROBLEM IS WIDESPREAD

Industry politics and competition being what it is—cutthroat—many people would like to single out Gilliam and TDI for abuse; but, unfortunately, the problem of responsibility appears to be more widespread. Bob Raimo said, “I’ve seen IANTD do bonehead things, too. Tom Mount lists me as a rebreather instructor, and that was before I became a rebreather instructor trainer with Rob Palmer. What the fuck did I know about rebreathers?! You know what my experience was on rebreathers when he listed me? Zero. The only thing I knew about rebreathers was what I read in aquaCORPS Journal, f’r crissakes. I wonder how many nitrox instructors are out there that don’t know anything about nitrox. I know they’re out there.”

I Heard the Wah-Wah

As told to aquaCORPS by Bob Raimo

Joe Odom asked me, “How deep are you gonna go? We want to go deep.”

I said I’ll go as deep as I feel comfortable with. I don’t care how deep you guys go. When I say that’s enough for me, I stop, and I come up, irrelevant to what you guys are doing. I said I’m not here to set any personal records, or industry records. I’m here to have a good time.

They all dove single 80s. I was very uncomfortable diving with single 80s, so I jerry-rigged some telephone wire to an 80 stage bottle because I refused to go deep on a single 80. I wanted to at least have a back-up bottle.

On the first day, I dove deep I was completely in control; I was completely capable of helping somebody else, which is my measurement of my comfort level. If I feel that I cannot help somebody else, I’m in over my head. I don’t like being able to just take care of myself. I like to take care of someone else if there’s a problem. If I can’t, I have no business being there. And I did not feel that way at 300 plus ft. I felt fine. I mean, I was narked, but I checked my gauges, and stopped at 250 ft/76 m on the way up in case somebody needed air.

On the second day, I’m diving a Dive Rite Transpac with a travel wing, which is only 30 lbs. of lift, and I’m wearing an eighth inch shorty. When we did the second dive, we were out on this cable—it’s in 7,200 ft/2,194 m of water, and over 21,000 ft/6,400 m long. The buoy is approximately 75 ft/23 m in diameter. It’s big. You could have a party for 100 people on top of this thing. There is no bottom reference.

I made two big mistakes. I grabbed my weight belt from my rebreather instead of the weight belt for my single 80. So, there’s an extra eight pounds of lead on my belt, and I’m completely oblivious to it. Bret wasn’t diving this day. Bret and Joe were saying that one of the things that you need to be able to do if you’re going deep is you want to get down there fast, and get out of there fast. I said, well, I couldn’t keep up with you guys. They asked how I came down? Well, I kinda floated down like I normally do.

Joe said there’s a lot of drag that way, you kinda have to go down head first. I’m like, I never go down head first. I said I’d go down head first and try and keep up with you guys. So I jump in the water and go behind Joe Odom, and I’m swimming upside down, straight down. I’m kicking to go down to keep up with Joe. I couldn’t keep up with the sucker; the guy is quick.

I never discussed with any of them how they do it. And none of us went to the Bahamas with any of this in mind. If I’d have known the week before, I’d have brought some clips and hooks and stainless steel tank bands. I’d have come ready to make real stage bottles, not use telephone wire.

I have no concept of how deep I am…’cause I don’t look at my depth gauge. If I know I’m going deep, I just try to stay in tune with my body. When I don’t feel good, it’s time to come up. And sometimes, if you look at your gauge and you see a big number, it scares you: Oh, omigod, and all of a sudden, adrenaline, a little bit of CO2, and it makes you worse off than you are. So I like to go down; I’m comfortable. But what was uncomfortable initially was my descent. It was an abnormal descent for me. I’m used to floating down, now I’m swimming down. I’m exerting myself kicking trying to keep up with this sucker.

At one point I’m saying, this is about my tolerance. I was really getting narked, I’m at the limit. If it gets worse than this, I won’t be able to help anybody. And as I’m starting to think about this, I look at my depth gauge and it says 340 ft/104 m and Joe Odom turns around—he was below me; he was the lowest guy on the line, and I don’t know who’s behind me at this point, if anybody—and Joe looks at me and I give him a clear-as-day signal of “I’m stopping here.”

I take my arm and sweep it slowly back and forth saying I’m leveling off. Joe gives me the okay sign. I start inflating my BC. After Joe sees me inflating my BC—because I could see him watching me, making sure that I was okay—he then turned and continued going deeper, figuring I was okay. Which at that point I was. I don’t know that if Joe had had a problem that I could have helped him by going deeper; but anybody at my depth and shallower, I was okay.

So, I’m inflating my BC and I’m going deeper and deeper…348 feet, 350, my BC’s full, 352, and I’m not feeling too happy. I went from feeling really good to feeling really narked. This is where I made what I believe to be the second and almost fatal mistake—I kicked. I used my legs, which is the normal diver reaction. At that point, I just wanted to stop. Not even to go up, just to stop.

I took one or two kicks and I went from being completely in control and just about capable of helping someone, into a complete head spin. That one kick used so much O2 and generated so much CO2… And I was like, WHOA, man, I got really fucked up. And it happened again, and I went, WHOA man…and thank god for that cable.

I took one or two kicks and I went from being completely in control and just about capable of helping someone, into a complete head spin. That one kick used so much O2 and generated so much CO2… And I was like, WHOA, man, I got really fucked up. And it happened again, and I went, WHOA man…and thank god for that cable. I just reached out with my right hand and—ka-chink—barehanded. This cable had fish hooks on it and was encrusted with all kinds of shit. But believe me, I was so numb, I didn’t feel anything. I just grabbed onto this cable. I looked at my depth gauge again, and all the pixels were lit up on my screen.

I had no idea how deep I was. For all I knew, I was at 500 feet. I knew I had inflated my BC and my BC wasn’t going up. I had about 1,400 psi left in my main cylinder, and I’ve got the stage bottle on me. So I decide I’m going to do this kick and I’m going to pull on this cable. I’ve got to reduce the pressure. I want to scream out of here and I’m gonna stop when my depth gauge says 100 ft/30 m. Now, mind you, I can’t read it.

By now, I’m assuming I’m pulling on the cable. Mitch Skaggs, who was at 325, said later that I went by him, but I never saw him. He could have been behind me when I passed him; it’s easy to miss people going up and down. He said I had one hand up in the air, my eyes were rolled up in my head, and he thought I would wake up on the way up. That’s how I felt: I needed to wake up.

One thing that really scared me was this noise. When I couldn’t read my gauges, I heard this noise—wah-wah-wah-wah—really loud. I didn’t know what it was. When I heard the noise, I could not see my hand on the cable. All I could see was my gauge. I couldn’t see anything else—everything surrounding the gauge was black.

One thing that really scared me was this noise. When I couldn’t read my gauges, I heard this noise—wah-wah-wah-wah—really loud. I didn’t know what it was. When I heard the noise, I could not see my hand on the cable. All I could see was my gauge. I couldn’t see anything else—everything surrounding the gauge was black. And I’m sure I started to breathe really heavy when I heard that noise…of course, more CO2 build-up.

I’m thinking: the next thing that’s going to happen is that I’m gonna black out, and I said to myself, “You’re not gonna black out. When this gauge says 100 ft, you’re gonna stop and do deco.” That’s what I said to myself my entire ascent: “You can’t black out, you’ve gotta do deco. You can’t black out, you’ve gotta do deco.” I kept kicking—at least I think I was kicking, I might not have been. This may have just been my thought process. I have to go on what other people say because I don’t know.

I had a very, very strong desire to live. I really believe staying focused on going to 100 feet to do deco saved me. I haven’t spoken to a lot of people about this, but at the worst point when I was really fucked up, I can understand how people give in to the euphoric feeling and die in deep water black-outs. Because as scared as I was, I felt fuckin’ good. I don’t know how you can say you feel good and think you’re gonna die at the same time. But I can say this: I could have very easily said, “Oh, fuck this.” And died.

I can understand how people give in to the euphoric feeling and die in deep water black-outs. Because as scared as I was, I felt fuckin’ good. I don’t know how you can say you feel good and think you’re gonna die at the same time. But I can say this: I could have very easily said, “Oh, fuck this.” And died.

But I’ve got a two-year-old boy; I’ve got a wife. I thought about that when I was starting to get that blacked-out feeling. I saw my son on that dive. I said, “I’m not leaving the kid, what am I stupid? I’m going to 100 feet and I’m doing deco.”

So, I think I’m pulling myself up this cable, and at about 175 ft/53 m, I can see blue in the background: everything’s clearing up. I’m starting to see some divers again up above me at 130 feet, 150, and I can read my gauge, I can read my pressure gauge—I’ve got 1,000 psi. 175 feet, 150, 140. I get to 100 ft, I dump the air out of my BC, and I say “Thank the fuckin’ Lord.” I do my Hail Marys and Our Fathers, I swim up to 40 feet, I start my deco, I go over to the 60/40 mix, and I do my deco.

During my deco, Joe Odom swims over. I write on my slate: “Scared myself today,” and pass the slate over to him. He writes down: “Were you in control?” I write: “I thought I was, but wasn’t.” So we get out of the water and I describe to him what happened on the dive. And he says that noise is very typical. If someone hasn’t heard that noise, then he hasn’t been that deep on air. That’s called the “wah-wah.” He says when you hear that noise, you’ve been fucked up on air, you’ve been deep on air.

I’m a damn good diver, but I don’t do deep air diving. If it wasn’t for all of my years of training, all of my years of acquiring knowledge, and general good diving skills, and the strong desire to live, I can understand how people just give in and die.

I probably learned more on that dive than I could do in a hundred dives…about dive ability, about the physiological true effects of gases on one’s body, why we shouldn’t be diving deep on air. I learned an awful lot about my own ability, tolerance, and desire to live.

Calling a Wah a Wah

By Michael Menduno

Definition: “Technical diving is a discipline that uses special tools and methods to improve underwater safety and performance enabling a diver to conduct operations in a wide range of environments and perform tasks beyond the scope of recreational diving.” technicalDIVER 3.2, OCT92

In our book, scuba diving to 400 ft/122 m plus on air without a back-up is NOT technical diving. Regardless of whether or not the divers could handle the narcosis, could tolerate excessive oxygen levels for brief periods (PO2=2.8+), or were within the thirds rule (I argue that they were outside the intent of thirds based on the absolute volume of gas—80 cf—that they carried for their 440 ft/134 m dive), the defining factor of these dives was the decision to dive without a back-up system and without first-stage redundancy. By doing so, divers’ lives were put at risk unnecessarily for no good reason.

Without a first stage back-up, a burst O-ring or a regulator failure would have most likely resulted in the death of one or more divers. In the event of equipment failure, it is also unlikely that one diver would have been able to bail out another at depth. Even if they had a long hose. Reportedly, no one did. The divers were not self-sufficient—a fundamental tenet of tech diving.

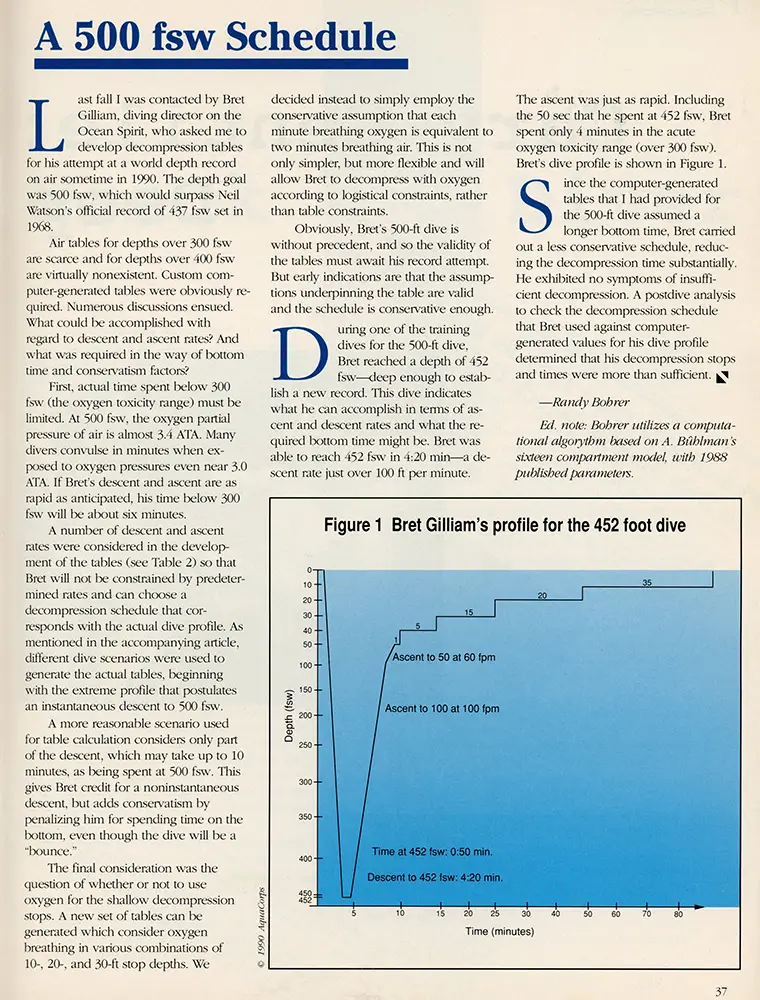

I asked Gilliam, after his then-record setting air dive to 452 ft/ 138 m in 1991, what his reasoning was behind making a deep air dive without first-stage redundancy. He responded, “How often does a regulator fail?” Talking tekkie? How often does it need to beyond 400 ft/122 m? Gilliam argued that the drag of an additional regulator [with dual valve—ed.] increased risks more. I disagree. That’s not tech diving. It’s gene-pool math.

I am concerned that people will associate wah-wah diving with technical diving and give the community a bad name. Worse, it will get divers killed.

Aren’t you the people—owners and instructor/trainers—who are setting the training standards? What kind of example do these dives set? The kind that led the 27-year-old Florida deep air diver whose life was recently terminated during a 475 ft/145 m world-record practice run to believe that he had something to gain?

Or that conveys the message that operational standards really don’t mean anything? Not if you are really experienced. Guru stuff. Worse. What does it say about your personal and professional commitment to diver safety? Hello.

The wah-wah dives were conducted as a private affair among industry insiders, but these were public figures. NSS-CDS chairman Odom argues that “Do as I say, don’t do as I do” has been the rule, not the exception, since day one. Maybe in the old days when diving beyond 130 ft/42 m on scuba was taboo. Wasn’t that one of the reasons that technical diving came out of the closet to begin with? You can’t have it both ways.

My advice? Just say NAH to the WAH. It won’t make your weenie any bigger, and if things go wrong, it could ruin your whole day. It’s your call. Mind them PO2s.—M2

aquaCORPS supports the consensus standards that we published as “Blueprint For Survival Revisited/‘ N7/COMPUTING, in /JUN93. It is important to note that these are operational, and not training guidelines. Here are some of the relevant sections covering the Wah:

GAS SUPPLY: Always dive an appropriately redundant breathing system—minimally first and second-stage redundancy—in an overhead environment, or when diving in open water beyond about 60 ft/18 m.

GAS MIX: Maintain your PO2s below 1.45 atm (about 200 ft/61 m) during the working phase of the dive and anytime more than light work is being done, boosting oxygen levels to a maximum of 1.6 atm with care during resting decompression.

Just say NO to nitrox mixes, including air, beyond about 180-200 ft/55-61 m or less, depending on the operation and environment. In particular, keep equivalent narcotic depths (END) as shallow as operationally and economically feasible, preferably 150 ft/46 m or less. [ENDs are being run as high as 300 ft/92 m on extreme deep self-contained dives to ameliorate HPNS. See aquaCORPS #11 Xplorers, “Absolutely Risky Business”.]

Note that the US NAVY and ADC Consensus Standards operational limits for air diving are 200 ft/61 m.

A Word from the Wahs

In the “Call of The Wah-Wah” by managing editor Dean Mullaney, aquaCORPS, #11 Xplorers, we chronicled a series of extreme air dives that were led by the heads of two technical training agencies during a week-long instructor training seminar in the Bahamas, and that nearly resulted in the death of one instructor trainer.

The four-hundred-foot-plus dives were conducted on air (PO2=2.8+) using single aluminum 80 cf cylinders without backup regulators or bailout bottles, reportedly while technical training dives were being conducted from the boat, and clearly outside the consensus safety guidelines established by the technical diving community [See “Blueprint For Survival,” N6/Computing, N12/Survivors].

It is aquaCORPS’s position that “Wah Wah diving” is extremely dangerous and represents the antithesis of the technical approach, i.e., IT IS NOT TECHNICAL DIVING. Furthermore, we believe that industry leaders have a responsibility to set an example for others, particularly for those who are just entering the field. We question what kind of example is being set by these dives. Hallo?

In running the story, it was not aquaCORPS’s intention to malign specific individuals or their agencies. We ran the story because it is our job to call the community’s attention to behaviors which, in our opinion, jeopardize the credibility that the technical diving community has worked so hard to achieve—and worse, that will get divers killed. How did the featured parties explain the call of the WAH WAH? Here’s what Gilliam and Odom had to say.

No One Else Can

by Bret Gilliam

The last issue of aquaCORPS contained an article commenting on extreme deep diving on compressed air. Although the author’s intent may have been noble, the factual circumstances of my involvement were unfortunately distorted and inaccurately reported.

First of all, I doubt if it is any surprise to anyone that I dive deep on air and other mixes. I’ve written best-selling books on the subject, authored scores of magazine articles, and lectured extensively all over the world on precisely this discipline. I’ve also been one of the most ardent proponents of modern extended range training that includes observation of responsible operational limits for oxygen and narcosis exposures to keep the great majority of divers within reasonable windows of risk. And the methods and standards of training that persons like Sheck Exley, Hal Watts, Tom Mount, and I developed over the last three decades have proved to be excellent guidelines for divers when combined with hands-on practical diving under the supervision of trained professionals.

But there is a big difference between training and what I may choose to do in my own personal diving. As a function of training, I never conduct any diving beyond the recognized general population exposures. For compressed air, this means a maximum of 220 ft/68 m. In fact, both IANTD and TDI recommend keeping training at 200 ft/61 m since this allows a certain factor for error should it be needed.

On the other hand, I make my living as a professional diver and photojournalist. My clients have included the US Navy, various scientific groups, commercial companies, and a host of publishers for book and magazine projects. I also perform a variety of consulting and testing roles for equipment manufacturers and specialized support OEMs. Often, my work involves extremely deep exposures, and it’s up to me to make the call on the best method of getting me and my cameras to a job site. In many cases, I get the job because, quite literally, no one else can do it.

“Often, my work involves extremely deep exposures, and it’s up to me to make the call on the best method of getting me and my cameras to a job site. In many cases, I get the job because, quite literally, no one else can do it.”—Bret Gilliam

I have to be a mobile swimmer and maintain the ability to handle cumbersome, bulky camera systems in extreme depths around subject matter that can include such diverse assignments as high-speed military submarines, deep submersibles, sharks, and whales. In many situations, compressed air allows me more flexibility in my gear package and a friendlier decompression than trimix. But what works for me will not work for others, and I am constantly afraid that less qualified and less experienced divers will attempt to dive beyond their abilities and hurt themselves.

That’s why, over the years and in all my published works, I have leaned in favor of more conservative exposures as a guideline for the average diver. It’s not to say that I will apply those same limits to my professional work. And there lies the most important distinction in a lot of this discussion. I’m a professional who gets paid extremely well for taking risks as an observer or photographer who can chronicle the underwater world where only a handful can even dream of visiting. I’ve been contracted in a lot of situations to do dives where submersibles were unavailable or impractical. In other assignments, I’ve been able to get in the right situation with a still or movie camera where a sub or surface supplied diver would never be able to maneuver. And on other work with marine life, I’ve developed proprietary equipment and decompression profiles that no one else has.

Because, boiled down to its essence, diving is simply a means of getting me to my work place. It’s incidental to me how I get there and support myself if I don’t get the work done that the client has paid for. And believe me, I’ve never had a contractor that was paying me several thousand dollars a day question my choice of diving gear if I came back with the results they wanted.

The facts are that, in many scenarios, I can function better with a very minimalist gear package since I have a rather extraordinarily low air consumption rate. My adaptive reflex to deep air diving after some 25 years of experience allows me to work comfortably in depths that reduce most others to incapacitation. But I am quite at home deep and the best evidence of that is the images I bring back and the detailed observational reports I can accurately produce. That’s what separates the professional who makes his living plying a hazardous trade from the weekend diver (no matter their “technical” experience).

What I do outside the scope of training is my own personal decision and should not be held up to unreasonable scrutiny by critics. Because, to paraphrase Charles Barkely, “I’m not a role model,” and I don’t want to be.

The sensational article that was published in aquaCORPS’s last issue was not something I intended to contribute to. I intended my remarks to be off the record and not for publication. Not because I had anything to hide but for fear that less qualified divers would seek to emulate dives by persons like myself or Joe Odom and get killed. We’ve already seen that happen, and no matter how many times we tell people that reading a book or doing a few bounce dives is no substitute for full time involvement, a couple people disappear every year trying dives way beyond their ability. And that’s the real tragedy.

Training works just fine within its limits. But I’m not about to tell explorers like Jim Bowden or guys that want to dive the deepest wrecks that they can’t pursue that calling. Because it’s a personal decision that each diver makes for themself and it’s nobody else’s business. And the self-appointed soap box critics who hide behind anonymous quotes ought to stay in the shallow end of the pool where they belong.

What works for me is individual. That’s why I don’t like diving deep with any but a handful of others. I can look after myself just fine, but it really throws off my equilibrium to have to worry about another diver whom I just naturally expect to screw up. So, please, leave me alone to do what I do. And I promise not to make fun of your day-glow wet suit or your wife’s hairdo. Is it a deal?

Bret Gilliam is the president of TDI, editor of Scuba Times’ “Advanced Diver Journal,” and a freelance writer/photographer.

Critics Don’t Count

by Joe Odom

Each diver has a view of what is important to them, what represents a limit, and what represents a threat to their way of thinking or even their life. Any attempt to alter their thought process often results in conflict.

Where is the proof that a PO2 of 1.6 atm represents safety? Does crossing this line immediately mean that there will be a physiological change? Or, do a myriad of other factors enter into the complex human equation to determine if an oxygen convulsion will take place? It is simply convenient to establish a limit for fledgling divers so that they don’t become bored with huge volumes of conflicting data that belie the original intent of the limit. Interestingly, the USN Diving Manual describes incidents at oxygen pressures of just 1.3 atm [At least one commercial operator has logged oxtox hits below 1.6 atm—ed.].

Will our technical divers be willing to give up the ground (depth) that they have so desired? Hardly. The reality of deep air “spike” diving is such that the actual hazard is the nitrogen and not the oxygen. Numerous sources noted in a wide variety of medical texts and studies associated with hyperbaric exposures of oxygen frequently describe subjects being exposed to oxygen pressures well in excess of 2.0 atm and up to 3.7 plus atm.

Reliability of today’s equipment enters into the equation as do the actual dive conditions. I have tried to think of any first stage failures I have experienced—can’t seem to remember any. The only one I personally witnessed was a cave student back in the early ’80s who insisted that his regs were the best made, he took great care of them, etc. They kind of let him down ’bout the Lips [a site at Ginnie Springs]. Seems he ignored the recall. Anyone who wants to contrive a scenario for failure can simply conjure one up—either based on actual possibilities or speculative ignorance. Since it’s made up, it’s easy to attack or defend depending on who shouts the loudest. Just some food for thought.

Strong sentiments sometimes get in the way of rational thought and may be further clouded by confusion over rules vs. recommendations. Once, as I stood on the fantail of a boat, saying farewell to a fellow diver [who died—ed.], I noted that the deep divers aboard nodded in agreement, while others just couldn’t understand why it had happened. It just did— the result of the choice of an individual who had a belief in his ability.

Anytime there is a statement, an observation or new idea, fifty percent of the people are for it and fifty percent are against it. The problem is that the fifty percent against it are so darn loud!

Does a diver have the right to choose if he or she wants to “go deep?” I should hope so. Can extreme deep air diving be “safe?” I doubt it, for safe means without risk. The choice needs to be made in concert with the diver’s desires and goals balanced against the wishes of their immediate family. Maybe that is why so many explorers were single. I personally have no desire to establish the record for deep air diving. This is because I catch enough grief from my wife as it is, but I am truly happy at my own personal limits—which vary daily.

I don’t encourage anyone to do anything they don’t want to do or are not willing to work and study hard for. Many diving pontificators cannot read simple physics, chemistry, or bio-physiology articles without missing the real point and totally blow the entire work out of context. Others publish data or formulas with gross errors and total disregard to scientific reality. When Wes Skiles introduced me to structured cave diving, a significant amount of time was spent on the physiology of cave diving risk acceptance. It was widely known back then that all cave divers had a screw loose; we just had to figure a way to make sure it didn’t back all the way out! There was a practicality to the step-by-step technique of exploring one’s limits. Today, many just want to pay their money and get the card in the “minimum time.”

I have also noted that, with any statement, observation, new idea, or old idea, fifty percent will say it’s showing off, fifty percent will say it’s the individual’s prerogative. The problem is that the fifty percent against it are so darn loud!

A cave and technical diving instructor trainer, Joe Odom is the current chairman of the National Speleological Society’s Cave Diving Section.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Remembering Bret Gilliam by John Bantin

InDEPTH: aquaCORPS’ Letters to The Editor (1990–1996)

InDEPTH: Examining Early Technical Diving Deaths: The aquaCORPS Incident Reports (1992-1996)

InDEPTH: Blueprint for Survival 2.0 by Michael Menduno and Capt. Billy Deans

The Great Dive Podcast explored the issue of the Wah-Wah in a three-part series and tribute to legendary character Bret Gilliam. Here they are:

The Great Dive Podcast: Episode 343 – Sex, Drugs, Rock and Roll, and Diving. The boys continue their look back on the life of the legendary Bret Gilliam and read one of his most controversial articles. They also revisit the comments from an online discussion board at the time. A fight had started for what technical diving was and deep air was the first battle. Is it Technical Diving just because we are beyond recreational limits, or was that term going to mean we did something different?

The Great Dive Podcast: Episode 344 – The Call of The Wah Wahs vs. Personal Responsibility

The Great Dive Podcast: Episode 345 – I’ve Heard The Wah-Wah The Wah-Wah continues. Join us as we talk the truth about diving deep on regular old air with Bob Raimo and Michael Menduno. Last week we mentioned how Bob almost died; this week we go through his personal memoir of the dive.

DOWNLOADABLES

InDEPTH: Annotated Tekkie posters. These posters can be downloaded and printed at a local print shop or saved as PDFs.

aquaCORPS #4 MIX was published in JAN92 just before the “Enriched Air Nitrox Workshop,” held prior to DEMA in Houston, Texas. The MIX issue focused on mixed gas technology. It was also the first issue of aquaCORPS that included the tagline, “The Journal for Technical Diving,” a moniker coined by founder and publisher Michael Menduno in 1991. Sponsored by DeeperBlue, Dive Rite, Fourth Element and Global Underwater Explorers

aquaCORPS #5 BENT was published in JAN93 in conjunction with the first technical diving conference, tek.93, held just before the annual DEMA show in Orlando, Florida. The issue focused on decompression illness (DCI) and presented the latest thinking on the theory, classification, treatment, and human factors associated with DCI. Sponsored by DAN Europe.

aquaCORPS #6 COMPUTING was published in JUN93 following aquaCORPS’ first technical diving conference, dubbed tek.93, held in Orlando, Florida in January of that year. The issue focused on dive computing and included interviews with nitrox computer developers Randy Bohrer (Bridge), Kevin Gurr (ACE), Paul Heinmiller (Phoenix), an interview with Karl Huggins (EDGE), and a story about commercial decompression software developed by decompression engineer, JP Imbert. There was also a review by Dr. Bill Hamilton and John Crea, of four desktop decompression programs that had recently been launched in the tech diving market. Sponsored by Shearwater Research!

aquaCORPS #7 C2 (Closed Circuit) was published in January 1994 just prior to the 1994 tek.Conference and DEMA show held in New Orleans, LA. The issue focused on rebreather technology, and we planned it as a primer in anticipation of aquaCORPS Rebreather Forum, scheduled to be held in Key West, FL that coming May. At the time, there was only a few dozen rebreather in the hands of sport divers. Sponsored by Divesoft