Diving Safety

How Current Are Your Rescue Skills?

How current are your rescue skills at your level of diving? Would you be able to rescue a tech diving team mate from a depth of 30m/100 ft? How about 76m/250 ft? What if they were unconscious? What if it was in a cave? Public safety instructor Wally Endres and instructor Christine Tamburri review the state of emergency preparedness and currency in the community, particularly when it involves tech diving, and offer some recommendations. Your teammates are depending on you!

By Wally Endres and Christine Tamburri. Photos courtesy of the authors unless noted.

Please take a few minutes and complete our Rescue Skills Survey.

When was the last time you had an in-water emergency while diving where your reaction saved a life? Maybe we should ask a more critical question: was it an event or was it actually an emergency? Are you a proactive or reactive diver?

When planning for a worst-case scenario, most divers consider the basics. These may include an Emergency Action Plan (EAP), Emergency Contact Information (ECI), dive accident insurance, emergency oxygen, a redundant gas plan, and so on. While many divers do some type of emergency preparation, most do not, and even fewer practice the critical skills that may make the difference between life or death during a dive accident, especially an in-water rescue scenario.

In 1984, PADI introduced their Rescue Diver Course, which gave a pathway to recreational divers who were looking for continuing education opportunities. Over the years, most other training agencies have developed their own curriculum, and many new divers quickly set their sights on becoming rescue-certified shortly after their initial open water training.

But what is the difference between training and a real-life scenario? Logic assumes the difference is monumental, but is it? Are divers prepared to perform a self-rescue, let alone handle other problems, especially in the technical realm? And what about instructors? Are they prepared to teach a rescue course having gone through their initial training ages ago? Let’s splash into the world of diver rescue, analyze how prepared divers really are to act, and examine a few solutions that can make diving safer.

The Standard Training Progression

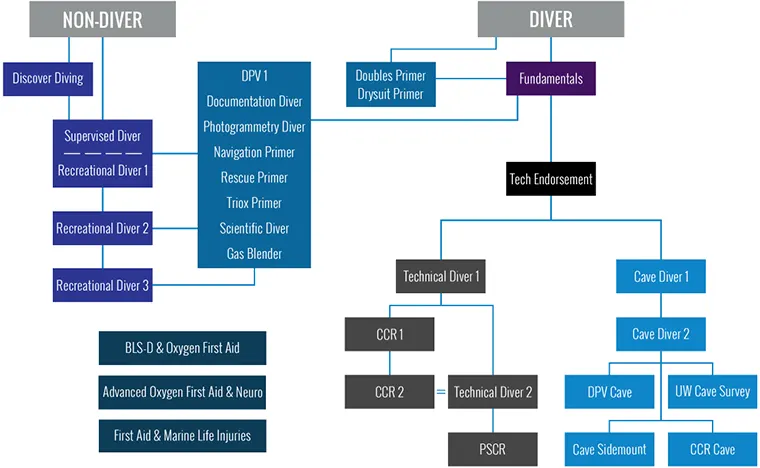

Initially, most divers follow a standard training progression. They start as an Open Water Diver, become an Advanced Open Water Diver, then become a Rescue Diver. This path is often straightforward, while some divers choose to take small detours along the way in order to complete specialties such as Nitrox, Deep, or Wreck training. Of course, not all training agencies follow this path and many call their specific courses by different names, but generally speaking, a majority of divers follow this kind of training progression.

As divers consider becoming rescue-certified at the recreational level, they need to consider certain prerequisites depending on their agency of choice. Here are four (4) for comparison:

| Agency | Minimum Age | Minimum Certification Level | Minimum Number of Lifetime Dives |

| GUE | 16 | GUE Recreational Diver 1 or GUE Fundamentals (Rec Pass) | 25 |

| SDI | 18 (10 with Parental Consent) | SDI Advanced Adventure Diver, SDI Junior Advanced, Adventure, or equivalent. | 15 (If Minimum Certification Level is Not Met) |

| PADI | 12 | Adventure Diver/Junior Adventure Diver, or equivalent, with completed Underwater Navigation Dive | None |

| NAUI | 15 | NAUI Scuba Diver or equivalent | None |

Despite the differences in name, content, and prerequisites, there is one commonality across all training agencies: A diver does not need a lot of experience to enroll in their initial rescue diver course. This means that they can take this training early in their dive career, only to go months or even years without practicing those skills. This creates the compounding issue of skill degradation as it relates specifically to rescue, and the weaknesses in a diver’s skillset may only present themselves when needed most: during a real-life scenario.

Categories of Divers

When examining the recreational dive industry as a whole, three distinct categories of individuals come to mind: Basic Recreational Divers, Technical Divers, and Instructors. When discussing rescue skill degradation, it is important to address divers of each skill level in each of these categories.

Basic Recreational Divers

The first obvious (or maybe not-so-obvious) point to mention about basic recreational divers, especially those who have not completed a rescue diver course, is that most of them have zero knowledge or experience as it pertains to handling a dive emergency. At least one training agency does dedicate a short section in their open water training to basic rescue skills, but most do not. Other agencies allow individual instructors to go above the written standards during their courses, but unless instructors add rescue skills into their basic training, students leave their early courses without that knowledge.

This obviously presents two main challenges:

- What if something goes wrong when two newly-certified divers make up a buddy pair and neither one of them has any training on diver rescue?

- What if one diver in a buddy pair has rescue training and the other does not? What if something happens to the only diver in the pair with rescue experience? How will the inexperienced diver respond?

Furthermore, to our knowledge, no training agency requires basic life support (BLS) or emergency oxygen (EO2) training for open water or advanced open water divers. The first few dozen dives for any newly-certified diver are usually fairly nerve-wracking, but what if something happens and there isn’t a qualified individual who knows how to medically respond to an emergency? Perhaps there is an Emergency Action Plan (EAP) in place for such a scenario, but how many instructors cover the topic of EAPs early in recreational training?

All that said, the term “basic recreational diver” does not necessarily refer to a new diver. Many divers take a rescue course, then stop their training progression due to not having any interest in starting down the path of becoming a dive professional. At first glance, these individuals may seem fully capable of handling a real-life dive accident. After all, they have completed rescue training, and may have been diving for years with thousands of dives under their weight belt. But how long has it been since that diver completed their rescue training? Have they practiced their rescue skills since?

The same goes for BLS and EO2 certifications—these divers needed to have that training to take their rescue diver course, but has it since expired? More importantly, when was the last time they practiced first response skills?

These are all things to consider. Almost all divers will inevitably find themselves as a buddy to a basic recreational diver, and these considerations must be understood before entering what is absolutely an Immediate Danger to Life and Health (IDLH) environment.

Technical Divers

The path to becoming a technical diver is detailed and long-winded, which is great for building experience in a variety of environments. That said, the consequences of technical diving incidents are much more significant than those in the recreational realm. Most divers who enroll in technical training have progressed through the recreational flowchart at least through a rescue diver course. Many have even taken steps to enter the professional ranks. That said, there are training progressions that allow divers to gain technical certifications without being trained in rescue, BLS, or EO2. This presents the same challenges that were just explored in the previous section.

Assuming that a technical diver has completed a rescue course at some point, the question shifts to:

- When was the last time a technical diver did any rescue training?

Perhaps it has been a few months or maybe a year, but more often than not, the answer to that question is several years or even decades! According to the American Red Cross, first response skills start to degrade within the first 12 months after certification without regular practice. In addition, BLS and EO2 certifications typically expire every 24 months, so unless a diver has maintained those skillsets, their ability to respond after an event is diminished. Imagine trying to perform an in-water rescue 10 years after completing training—a challenge that would be easy to understand.

Just because a technical diver has had previous rescue diver, BLS, and EO2 training does not mean that they are fully prepared to respond in the event of an emergency. The real questions are:

- Has that technical diver ever practiced rescue skills while wearing doubles, sidemount, or a rebreather?

- Has that technical diver ever rescued someone in doubles, sidemount, or a rebreather?

- Has that technical diver revisited all of their previous rescue skills with these configurations?

These are questions that very few recreational instructors consider, and at the time of this article being published, we are unaware of any technical-specific rescue courses within the dive industry, though some agencies train for rescue skills during their tech courses.

More gear equates to a more complicated rescue that will inherently require more effort. Is a technical diver prepared to withstand the physical demands of managing an in-water scenario? Tim Clements and Mark Powell (in collaboration with TDI and IANTD) set out to answer that question back in 2017 when they conducted a filmed experiment that measured heart rate during a simulated rescue scenario. The results are fascinating, and they should inspire every diver to consider the increased efforts required to carry out a rescue in a technical diving environment.

The last thing to consider is the artificial and actual overheads that are often created on technical dives: a theoretical decompression ceiling or a physical overhead inside a cave or a wreck. These elements further complicate a technical rescue, and can require technical divers to make heart wrenching decisions. What if a significant amount of decompression has been accumulated and a buddy has a medical emergency? Should decompression be omitted? What resources are available to get that buddy to the surface? Is surface support even available to manage the situation? What if a similar event happens 1524 m/5,000 ft back in a cave? Does the rescuer have the gas to get their buddy back to the surface? What are the physical demands associated with towing a diver 1524 m/5,000 ft? How will those increased physical demands affect the physiological and respiratory changes of a diver, especially those on a rebreather?

Rescue scenarios in technical diving are intense, chaotic, and unpredictable. Regular practice and topside preparation provide the best chance for a positive outcome, but the current state of the dive industry rarely addresses these during formalized training.

In the grand scheme of things, we preach skill, knowledge, and experience. Without these three elements, we risk the ability to manage the mental stress which can easily turn an event into an emergency. Mental stability allows us to work the problem and carry on to dive another day.

Instructors

Going back to the standard path of recreational training, it is important to understand the skill, knowledge, and experience of those teaching basic rescue courses. As stated earlier, divers may go months, years, or even decades without taking a rescue course or even practicing their skills. Unfortunately, it is often those same divers-turned-instructors who are put in charge of teaching rescue courses.

There is a trickle-down effect of inexperienced instructors teaching inexperienced divers that leads to minimum skills to manage in-water incidents. What’s worse is that the inexperienced diver may one day become an instructor, Course Director, or Instructor Trainer only to teach a rescue course based on what they learned in their mediocre rescue course several months, years, or decades prior.

DAN published an article in 2023 that addressed this very concern. “Teaching Rescue: Am I Qualified?” takes a deep dive into how quality instruction is lacking in most rescue courses and explores how that poor instruction is impacting the industry on a larger scale.

Finding Solutions

When it comes to rescue, there are a ton of gaps that make divers vulnerable to negative outcomes during an incident, but it isn’t all doom and gloom.

NAUI has taken strides to solve this problem by incorporating at least one (1) rescue skill into all of their major courses. Even their Open Water standards include rescuing an unconscious diver! This gives newly-certified divers an opportunity to both understand what can go wrong underwater and to get hands-on practice in assisting another diver. Likewise, Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) incorporates rescue skills including gas sharing, lost diver protocols, and recovering an unconscious diver in all of its classes. They also require instructors to demonstrate these skills as part of the bi-annual recertification. The National Speleological Society—Cave Diving Section (NSS-CDS) also incorporates rescue skills as part of its coursework.

There are also several instructors and agencies who host rescue workshops that allow experienced divers to keep their skills up-to-date and to learn new techniques. Some instructors have developed workshops designed specifically for other instructors to help them understand the behavior of students and explore ways to avoid problems before they occur. These training experiences are intense, and they cover everything from throw bags to BLS refresher scenarios to bolting diver management.

Other instructors have revamped their rescue course curricula to allow divers to wear doubles, sidemount, or maybe even rebreathers. This gives divers in recreational gear the opportunity to rescue someone in an alternative configuration, and it gives technical divers the opportunity to understand what a complex rescue may entail. Diver survival classes teach the nuances of self-rescue in a confined and controlled environment. This allows students to gain real-life experience in entanglement and gas management while calmly working through problems under the watchful eyes of a dive professional.

On the professional side, many Dive Safety Officers (DSOs) in aquariums and colleges host mandatory “in-service days” that depict a rescue scenario from start-to-finish. They sometimes even include participation from bystanders or local emergency medical services! Industry veteran and educator Tec Clark describes the intricacies of NOVA Southeastern University’s “in-service days” in his podcast series The Dive Locker, Episode 157. On the other hand, Public Safety Diving revolves around constant training to include all aspects of safety. After all, it’s in the name!

One initiative that could make the most impact, but is unfortunately not yet in practice, is requiring annual rescue refresher training for all instructors. This would give everyone who teaches rescue the tools to convey the most up-to-date and accurate information to their students to create safer, more comfortable, and more competent rescue divers who may one day go on to teach the very same course. The trickle-down effect described earlier would thus be stopped dead in its tracks.

Recommendations

All divers, regardless of their experience level, should be regularly practicing their basic rescue skills. At bare minimum, these are the skills that should be reviewed at least annually:

- Gas Sharing/Out-of-Gas Diver

- Unconscious Diver Recovery

- Diver Recall System

- Lost Diver Protocol (Based on Environment)

Divers are encouraged to practice these skills and more with their group of regular dive buddies. They can plan a weekend at a local dive site, grab some burgers and hot dogs, make an itinerary, and create a training event that is both educational and fun for all! Reviewing rescue skills should not be boring, and these events should create an environment that is free of bias so that every diver can identify their weaknesses and work to improve.

Emergency Action Plans (EAPs) and Emergency Contact Information (ECI) should be reviewed on a regular basis, or any time a component of either changes. In addition, BLS and EO2 certifications should be renewed every 24 months, or whatever is required by the specific training agency. These skills should also be regularly practiced. We dare say that a discussion of these things among buddies or the team is as worthwhile as the pre-dive check.

Skill degradation is real, and there is no exception when it comes to rescue skills. As an industry, several changes need to be made to address gaps in training, but that all begins with individual divers.

We challenge you to take the information in this article and apply it to your next dive. Practice a skill that has been dormant and identify areas that need improvement. Update your EAP and ECI, and encourage your buddies to do the same. Every step you take to make improvements in your own skillset may one day make the difference when you are called upon to save the life of another. Don’t get caught in the cycle of complacency—solve the problem before it begins.

Please take a few minutes and complete our Rescue Skills Survey.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Who You Gonna Call (in an Emergency)? By Buck Buchanan and Wally Endres with Christine Tamburri and Robert Zink.

InDEPTH: The Art of Surviving in a Hostile Environment By Wally Endres and Buck Buchanan.

DAN: Teaching Rescue: Am I Qualified? By Jim Gunderson and Christine Tamburri

IANTD/TDI: Diver Rescue Film IANTD TDI by Tim Clements and Mark Powell

EXTRA:

To be clear, most training agencies require an instructor at any level to have the basic rescue, BLS, & EO2 certifications as a provider but also be certified as an instructor of these courses. This notion is worrisome to an extent considering the overall lack of experience in most cases. Note however, that from a legal perspective, even if the BLS provider-level certification has lapsed several years ago and a diver attempted to perform CPR yet fails, the provider would be protected under the Good Samaritan Act from any negligence.

Wally Endres (NREMT, DMT) is the co-owner of Dive911, LLC, a Central Florida-based dive training facility that specializes in instructor professional development and public safety pedagogy. He is a Course Director, Public Safety Instructor, and former law enforcement officer who has 25+ years of experience in risk management operations and OSHA compliance consulting.

Christine Tamburri is an SDI Instructor under Dive911. As the former Risk Mitigation Coordinator at Divers Alert Network (DAN), she is committed to helping divers become safer, more comfortable, and more confident in the water. Christine is an avid cave and technical diver who spends every spare moment of her free time either cave diving or planning to go cave diving.