Diving Safety

The Art of Surviving in a Hostile Environment

We are one breath away from being a drowning victim on every dive. It’s a hard reality that divers need to understand and accept if we are to improve diving safety according to public safety and professional development educators Buck Buchanan and Wally Endres. The two take us for a sobering deep dive into the Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health (IDLH) environments, i.e., your favorite wreck, cave, kelp bed, or swimming pool and explain how to improve our odds of survival.

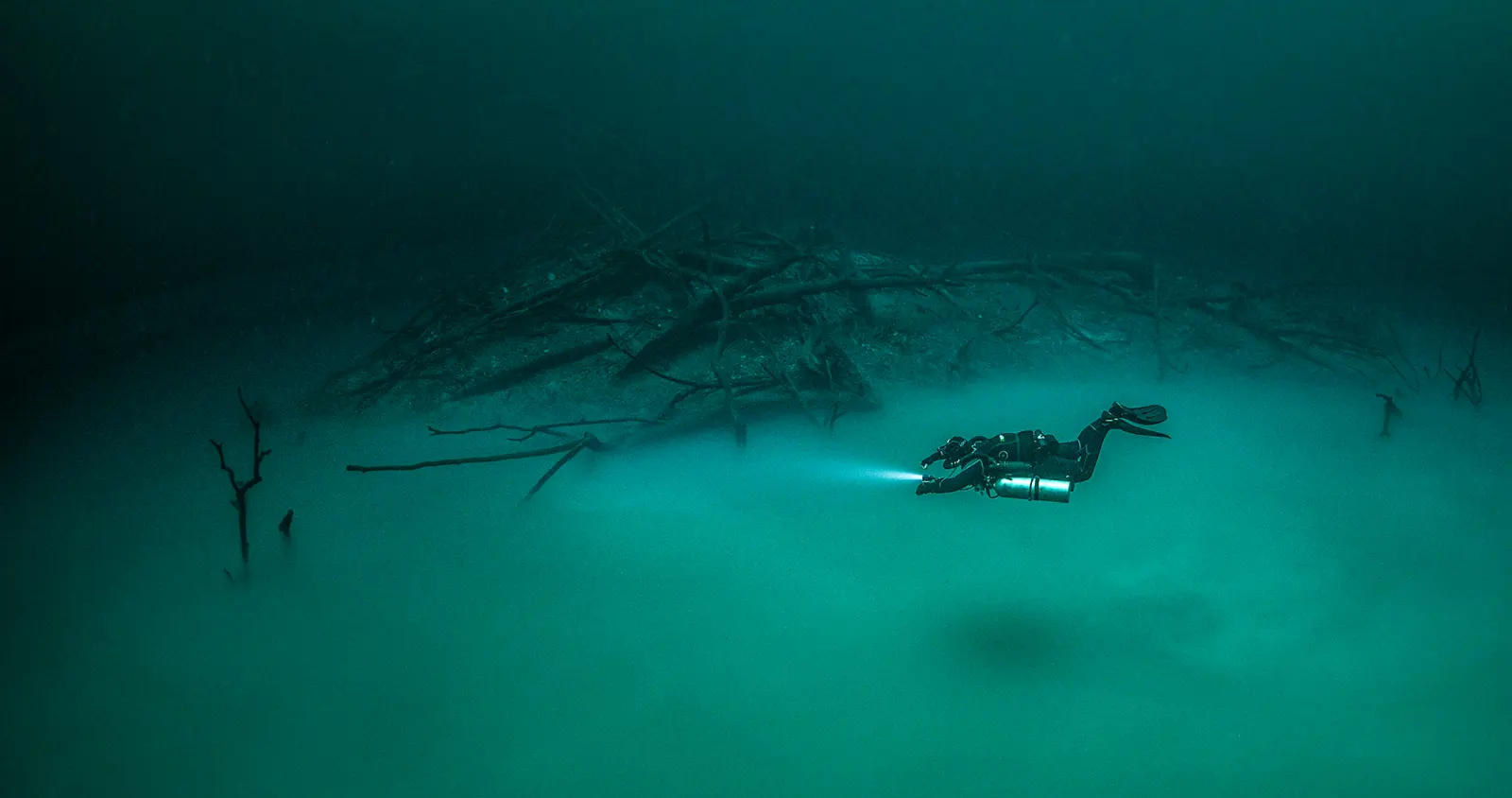

By Wally Endres and Buck Buchanan. Photos courtesy of the authors unless noted. Lead image: The late Ben Strelnick flying over the hydrogen sulfur layer at Cenote Angelito in Tulum, Mexico. Photo courtesy of Tom St. George.

On every dive, we are one breath away from being a drowning victim.

Let that sink in for a moment. Despite this statement sounding harsh, it is a reality that we all need to understand and accept. The fact is that humans were not meant to survive in the hostile, subsurface environment we dive in. No amount of planning, risk mitigation, or training will prevent all accidents from occurring. But why is this the case? A deep dive into the roots of IDLH environments may help to identify an answer.

Throughout this article, we’ll make references to public safety teams and commercial diving, but we must understand how all of this applies to the individual diver with respect to both recreational and technical diving.

What is an IDLH environment?

Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health, or IDLH, is most often discussed in commercial, public safety, and military diving operations. It is defined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) as:

“[A]n atmospheric concentration of any toxic, corrosive, or asphyxiant substance that poses an immediate threat to life or would cause irreversible or delayed adverse health effects or would interfere with an individual’s ability to escape from a dangerous atmosphere.”

In our case, our “atmosphere” is a subsurface environment and our “toxic” or “asphyxiant” substance is dihydrogen monoxide. If you can’t stick your head into a bucket of water and take a breath, you are in an IDLH environment.

These environments are crucial to understand in order to preserve life in hostile realms. But what is the core meaning of each letter in IDLH? Let’s dive a little deeper:

| Immediately: At any moment in time, an adverse outcome can result from an action or event. There is little-to-no delay in response. For example, a diver that runs out of breathing gas is immediately at risk of drowning if a redundant gas source is not available or the surface is not reachable. |

| Dangerous: The distinct possibility that the result of an action or event could end in harm or damage to a person, place, or thing. For example, a diver who has become hypothermic during an ice dive is in danger of being unable to extract themselves from the water. |

| [to] Life: Being alive, specifically the realization that it can end at any time as a result of an action or event. For example, a public safety diver who becomes entangled, has not received proper training, and has no cutting devices is in a life-threatening situation. |

| [or] Health: A person’s well-being, whether it be physical, mental, or emotional. For example, the physical health of a commercial diver who is working in a contaminated environment without proper personal protective equipment (PPE)* is at risk. |

*In the public safety world, we refrain from using terminology such as dive “gear,” as it would get mistaken for recreational SCUBA equipment by those who need to justify budgetary expenditures. When we look at items such as drysuits, full face masks, and communications, these are typically considered luxury items, but in the grand scheme of things, these are personal protective equipment (PPE). Dive teams mitigate the IDLH risks by wearing PPE as a barrier for contaminated water and they use full face masks to protect the airway. A tethered diver with proper PPE and communications is well-equipped to survive in IDLH environments.

These are just a few examples of incidents that can occur and have happened as a result of the subsurface environment being classified as IDLH. But who needs to be concerned with these environments? Do they only impact commercial, public safety, and military divers?

Who is impacted by IDLH environments?

Every diver, regardless of their classification, needs to understand, plan for, and respect IDLH environments. The topic impacts recreational and technical divers alike—and all dive industry professionals. It is also imperative that those who are considering diving, but are not yet certified, research IDLH environments and fully understand their risks prior to enrolling in a course.

Diving takes place in an environment where humans are not able to survive without the use of life support equipment. At any given time, those devices may fail, at which point we are immediately put in danger of losing our lives or having adverse health effects as a result of an incident. But dive gear is not the only concern. Some environmental conditions can put divers at risk of specific adverse outcomes. As an example, let’s examine a commercial diver who is working to make repairs inside of a confined space, such as a sewer drain. One risk of this specific environment is the possibility for the release of methane, which can form gas pockets above the diver. Methane is highly flammable and can contribute to sudden explosions when it reacts with oxygen. When the diver exhales and oxygen molecules are combined with methane, heat energy is released, and combustion can occur. This can put both the diver and the surface support team at serious risk.

Risk mitigation efforts are almost always available and can greatly reduce the chances of an incident. In the case of this commercial diver, constant gas venting, monitoring, and air quality checks should be part of the risk mitigation strategy. However, not all efforts will be successful, and incidents and accidents do still occur, so it is essential that all divers respect IDLH environments.

Why should divers respect IDLH environments?

IDLH environments do not discriminate based upon certification level or experience. Even the most seasoned technical diver or the most knowledgeable public safety professional may at any time be seriously injured or killed during a subsurface operation.

There are countless published resources available that detail dive accidents and incidents, many of which resulted in a fatality. Close Calls by Stratis Kas is one of the best examples. All of the stories are written in a first-person narrative by some of the most recognized names in the dive industry as they detail how they almost succumbed to an IDLH environment.

Even one of our own authors, with 35+ years of public safety diving experience, survived an incident that was immediately dangerous to his life or health.

Buck Buchanan (Co-Owner of Dive911) is a Public Safety Diver, Instructor Trainer Evaluator, and subject matter expert. In 2003, he was looking for a body and a vehicle in a lake in approximately 6 m/20 ft of water. Conditions were less than stellar with visibility around an inch or two. Upon identifying what he thought was a vehicle, he began a methodical search of the object. Zero visibility searching turned to tactile efforts simply to identify anything that may be obvious. Within seconds, he found himself “stuck” in a situation where horizontal and vertical movements were almost impossible, and realized he was trapped in a dark void. After a couple of minutes, Buck recognized an object that felt like a c-clamp, one that would typically hold a bed cap to the rails of a truck body. When he accidentally entered the “covered” truck bed, part of his tender line snagged the rear window of the bed cap, closed it, and trapped him inside. This created a real, life-threatening situation. Five seconds of a calm and collected mind allowed him to realize that he was in a familiar place, and that afforded him the presence of mind to remember that he was physically attached to his surface support team. Reversing his position and following the tender line gave him peace of mind to communicate with his surface support team and exit the vehicle without panic.

Another example of something simple that recreational divers frequently encounter is hydrogen sulfide: the wispy, cloud-like anoxic layer that is found in certain locations. While this gas is poisonous and flammable, divers can detect it simply by smell well before it causes health concerns on the surface. It is very apparent when a diver has been exposed to hydrogen sulfide, as their brass hardware will turn black. Hydrogen sulfide can also cause metals to corrode and it can result in yellow or black greasy stains when it forms metallic sulfides. It typically will not be a detriment to the internal parts of a scuba regulator, though proper gear maintenance and cleaning is always critical. Aside from being corrosive, hydrogen sulfide is a toxic gas that is created by bacterial colonies and decaying organic matter. Divers entering a gas layer may experience itchy skin, tingling, or dizziness. Prolonged exposure to hydrogen sulfide within an anoxic layer can lead to skin absorption and become a serious risk. In addition, transitioning from fresh or salt water through the hydrogen sulfide layer while diving can be truly disorienting and ultimately skew the diver’s judgment.

How can the adverse effects of IDLH environments be combated?

As best said by Lamar Hires in his original 1997 cave diving safety video titled “A Deceptively Easy Way to Die”:

“If I’m scaring you a bit, good. That’s the point.”

IDLH environments are not to be taken lightly. They demand respect from all of us. That said, we have the ability to combat their adverse effects through proper dive planning, risk mitigation efforts, and extensive training. When we are preparing for an adverse situation, we must ask ourselves, “Is it an “event” or is it an “emergency”?”

In an effort to prepare ourselves as divers, we use a WIN/WIN philosophy. The first part of this acronym is “What’s Important Next?”. This is a critical thinking approach to decision-making and we utilize this methodology from basic recreational diving, through the technical arena, and we reinforce it in all working diver environments. The second part of this philosophy is “Weight, Inflate, Notify.” This is a proactive necessity that allows the diver and the surface support team to be prepared when facing an event, as opposed to being reactive to an emergency.

On the topic of risk mitigation, let’s go back to our original IDLH examples:

| IDLH Example | Mitigation Solution |

| Immediately: A diver that runs out of breathing gas is immediately at risk of drowning if a redundant gas source is not available or the surface is not reachable. | To increase the amount of time a diver has to respond to an out-of-gas incident, they should start by planning their dive to ensure that they have sufficient gas, which should also account for an unforeseen catastrophic gas loss. This may lead the diver to wearing some sort of redundant configuration. Of course, the diver should receive proper training before carrying and utilizing redundant gas. With proper dive planning and extensive training, the diver in this scenario would not have experienced a true gas emergency, and this incident would have been classified as urgent, not “immediate.” |

| Dangerous: A diver who has become hypothermic during an ice dive is in danger of being unable to extract themselves from the water. | Pre-dive planning for ice dives must include an honest assessment of the limitations of every member of the dive team. For both the diver and the surface tenders, they must never reach a point of being unable to perform their duties or assist others in the event of an emergency. Proper training will ensure that an extensive plan is created before each dive and that proper dive procedures are followed. With these efforts, the diver in this scenario would never have reached a hypothermic state, and this incident would have been classified as inconvenient, not “dangerous.” |

| [to] Life: A public safety diver who becomes entangled, has not received proper training, and has no cutting devices is in a life-threatening situation. | Public safety diving is rooted in team operations and, as such, requires extensive planning to execute safely. In addition, proper training is essential for a diver to be able to perform life-saving skills when they are needed most. Furthermore, a properly-equipped diver will have the tools needed to survive even the most precarious incidents. With proper dive planning, risk mitigation efforts, and extensive training, the diver and the team in this scenario would have been able to work through this situation with ease, and this incident would likely have not been at risk of taking a life. |

| [or] Health: The physical health of a commercial diver who is working in a contaminated environment without proper personal protective equipment (PPE) is at risk. | Exposure protection, specifically from contaminants, is essential to protect any diver—especially commercial divers. Pre-dive planning must address such concerns so that proper risk mitigation measures can be taken to protect the health of those in and around the water. Furthermore, specific training in decontamination techniques is required for topside personnel. With proper dive planning, risk mitigation efforts, and extensive training, the diver in this scenario would have been fully encapsulated and protected from the contaminated environment, and this incident would likely not have been at risk of putting the health of the diver in jeopardy. |

There are countless methods to combat the adverse effects of IDLH environments. Regardless of the method, the dive team must ask three questions:

- Is it safe?

- Does it make sense?

- In a worst case scenario, will it work?

If the answer to all three of these questions is “yes,” there is a strong likelihood that the team will safely complete the dive.

In Summary

The key takeaway is respecting the subsurface realm for what it truly is: an IDLH environment that, at any time, can put a diver at risk of serious injury or death. Unless the human species mutates and grows gills, this will always be a harsh reality. With proper dive planning, risk mitigation efforts, and extensive training, we give ourselves the best chance of survival. And always remember: On every dive, we are one breath away from being a drowning victim.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: How Deep is Your Library by Christine Tamburri

InDEPTH: Who You Gonna Call (in an Emergency)? By Buck Buchanan and Wally Endres with Christine Tamburri and Robert Zink.

Divers Alert Network: DAN Annual Diving Reports

Scuba Diving: Lessons for Life by Eric Douglas

Amazon.com: Diver Down: Real-World SCUBA Accidents and How to Avoid Them by Michael R. Ange

The Human Diver: APPLY HUMAN FACTORS. MASTER THE DIVE.

Buck Buchanan and Wally Endres (NREMT, DMT) are co-owners of Dive911, LLC, a Central Florida-based dive training facility that specializes in instructor professional development and public safety pedagogy. Buck is an SDI/ERDI Instructor Trainer Evaluator and Ambassador who has 35+ years of experience in teaching, commercial diving, and heavy salvage. Wally is a Course Director, Public Safety Instructor, and former law enforcement officer who has 25+ years of experience in risk management operations and OSHA compliance consulting.