Community

Remembering Dr. John Zumrick

Cave explorer and inventor Bill Stone recounts being introduced to Dr. John Zumrick (1946-2021) by his mentor, the legendary Sheck Exley in the early days of Florida cave diving. He elucidates on the pivotal role the pioneering Navy doctor-cum cave diver played—not only in Stone’s own life but also in the early development of technical diving. Zumrick was responsible for introducing Stone to rebreathers and helped the fledgling community’s move to mixed gas technology.

by Dr. Bill Stone. Images courtesy of B. Stone unless noted.

In the fall of 1980, I was learning about deep diving on air from Sheck Exley. We had visited a series of ever-deeper north Florida cave diving sites—Orange Grove sink, Cathedral Chasm (then called Ghoul’s Sink), 40 Fathom Grotto (then called Zuber Sink), and finally Eagle’s Nest. When Sheck heard that I was training for a deep sump dive on the Huautla plateau in Mexico, he said, “You really need to meet Dr. John. He’s over in Panama.” Nothing more than that.

At the time I was thinking, “How would he know any divers in Panama and why would that be of interest to me?” Later I learned that he wasn’t referring to the namesake country of the Canal, but rather Panama City, Florida. And, it turned out, “Dr. John” was Commander Dr. John Zumrick, Assistant Chief Medical Officer at the Navy’s Ocean Simulation Facility, also known as NEDU, the Navy Experimental Diving Unit, where SEAL teams and other Navy divers underwent chamber dives to assist with decompression table development, as well as to test new equipment.

Sometime in September 1981, I was again with Sheck, this time to learn about stage diving. Toward the end of my one-week stay, Dr. Zumrick joined us for a canoe trip up-river to a place called Line Eater cave—an unremarkable outflow spring on the side of the Suwannee River. It was not all that big in the cross section, and the floor was deep mud. John was eager to teach me weird new cave diving techniques and he flipped over, went positively buoyant and began pulling himself along the ceiling and gliding, as if the overhead was the floor of the cave. I did the same and followed him.

We spent the entire dive that way and, when we finally reached the entrance, the inversion was unnerving. John smiled and said “How’d you like being a bat?” John was one of those people who did not exactly present as an Olympic-class athlete, and he frequently sported a waistline bulge. The stereotype that he engendered completely exploded when he got underwater: the man was a fish, and water was where he truly lived. I did not know it at the time, but John was going to play a pivotal role in my life—and that of almost every future tech diver—in the next few years.

The Early Days of Cave Diving

During the early 1980s, there was a very short list of frontline cave divers in Florida led by true pioneers such as Sheck Exley and Tom Mount, as well as Paul DeLoach, Clark Pitcairn, Wes Skiles, Mary Ellen Eckhoff, Court Smith, and Dr. Zumrick. Collectively, they set cave diving records that stood for decades and established the first rules of safe cave diving.

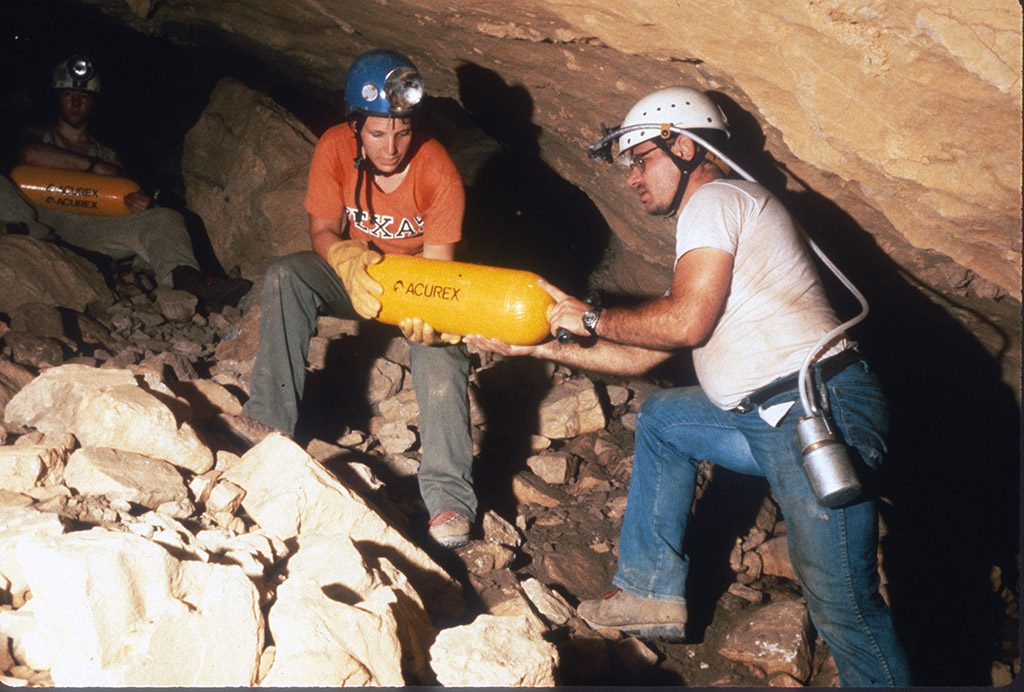

Perhaps it was simple fascination with the weird diving gear we had brought to Florida—the first ultralight composite high pressure (450 bar) diving systems that had been engineered for remote sump diving in southern Mexico—that drew Zumrick into our motley band of deep expedition cavers. Nevertheless, by the spring of 1984, he was a leading member of the eleven-person team that went to Oaxaca for four months to tackle the paleo resurgence for Sistema Huautla known as the Cueva de la Pena Colorada. It was, in fact, Zumrick and Clark Pitcairn who made the final push on Sump 7 there, to a depth of 55 m/180 ft at 200 m/656 ft penetration (on OC air).

Sometime in late April 1984, I had made my way back to our jungle basecamp with five of those composite tanks strapped to a backpack frame and ditched the load in front of our 5 x 10 m/16 x 32 ft netted mess hall. Inside, seated opposite each other, were Dr. John Zumrick and Dr. Noel Sloan, drinking tequila. I joined them as the sun set red over the canyon walls. It had turned out that, after three solid months of diving, John and Clark’s final push on Sump 7 was our last.

We had used 72 of those fiberglass tanks (each carrying around 105 cubic feet of air) just to get those two to that point, since there were six other sumps and two underground camps—the first ever set beyond underwater tunnels in a cave—along the way. As I walked in, Noel was complaining to John “. . . If we could have just packed more molecules of air in the damn tanks, we could have gotten through.” We had already been pushing our compressor and Haskel booster about as far as we could. I looked at him and said “Which laws of physics would you like to bend?” There was a pause in the conversation at which point Zumrick coughed and said, “You know, you aren’t so far off about bending the laws of physics. There are other ways to survive underwater.”

Have You Ever Heard of Rebreathers?

There was a long silence as we stared at John at which point I said “Okay, John, you’ve got our attention.” He then said something that marked the opening of a doorway, a bifurcation in the path of my life. He said “Have either of you heard of rebreathers?” From the blank looks we shared he nodded and said, “I thought so.” He then proceeded to give us an hour long lecture on the Mk15 and LARV rigs Navy SEALS and EOD divers were using and explained how they worked.

But John went much further. After our return from the expedition, he invited me to visit NEDU, and I took him up on the offer. I ended up spending three days there, reverse engineering the Mk15. I walked away understanding the potential power of rebreathers but also being solidly convinced that the Mk15 was not safe for cave diving. It was the beginning of a long road that led to the Cis-Lunar Mk1 rebreather in 1987, the commercial Cis Mk5 by 1995, and eventually the current Poseidon Mk7, all thanks to an idea planted by John Zumrick in April 1984.

Most cave divers (and many dry cavers for that matter) are aware of the staggeringly long labyrinth of flooded caves that runs up and down Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula east coast. Few are aware of how concerted exploration and mapping began there. Sheck Exley had gone on a diving vacation to Cozumel island in the spring of 1981. While there, he had heard stories of springs on the beach south of Cancun, on the mainland. He rented a single OC 80 cubic foot tank and regulator and, strolling south along the beach near Akumal, came across such a spring. Diving in, he noticed skylights in the spring tunnel to the west and dove from skylight to skylight for some 300 m/984 ft. That was as far as he went, and he never returned, but he did relate this story to John Zumrick.

When the 1984 Pena Colorada expedition wrapped up at the end of April, we were two weeks ahead of schedule with an eight-ton moving truck full of diving gear. It was Zumrick’s idea to divert to the Yucatan to see what Sheck had gotten into. During those two weeks, we dived dozens of entrances from Akumal south to Xel-Ha, locating many of the primary system entrances that would later become well known to all future cave divers coming to the Yucatan.

To myself and other dyed-in-the-wool expedition vertical cavers, the recon to the Yucatan coast had been a diversion to thank John for his extensive help over the previous two years when he helped me organize the Pena Colorada expedition and trained the team. To John, however, this was his own fork in the road. He loved the place. And he returned regularly from then on. John Zumrick, one of the first NSS-CDS cave diving instructors, trained Mike Madden and Jim Coke. Through those actions, and the stories of effortlessly laying kilometers of line without decompression, the word got out and the rest is history: It is entirely feasible that Ox Bel Ha will connect to Sac Actun and form the world’s longest cave (dry or wet). When the history of all that is finally written, Zumrick should be recognized for his pivotal role in starting it all.

The Mixed Gas Revolution

Many in the Florida cave diving community in the early 1980s were aware of a story from the 1970s when Court Smith and Lewis Holtzendorf decided to experiment with heliox for deep cave diving. The dive had gone well to 80 m/263 ft, but the decompression tables they used from the U.S. Navy called for pure oxygen at 15m/50 ft depth. Tragically, Holtzendorf toxed and drowned. His death created a taboo in the cave diving community over the use of helium. Not even a successful dive by Dale Sweet a few years later in Diepolders could shake that and, for a good six years, leaders like Hal Watts, Exley, and others preached that if you were going to dive deep, the only safe way was to use air and gradually train your body and mind to deal with the narcosis.

In the spring of 1985, I was with British sump diver Rob Parker who had been training for a deep air dive in the famous sump diving site at Wookey Hole in southwest England. We were in north Florida and had been to 60 m/197 ft in Diepolder II. We happened to meet Dr. John for breakfast one Sunday in Wakulla Springs and told him about how narked we had been and how unfortunate it was that we could not use helium. It was then that Zumrick was the vector, once again, for a second revolution in diving.

John had a funny habit of tapping the fingers of his left hand, in sequence, on the table when he was thinking about something and was deciding whether or not to say it. I saw this happening and stared at him, wondering what gem of wisdom was about to drop. He was by then Captain John Zumrick, USN, and Chief Medical Officer for the NEDU—a prestigious place to be if diving safety was your interest. He said, “You know, we’ve been running a lot of helium dives lately, and the decompression profiles are looking a lot like the extended exposure air tables.”

I said, “What are you saying, John?”

He replied, “It means that if you kept the oxygen fraction of air and the balance helium in your gas mix, you could use the extended exposure air tables for safe decompression.” It took a second for this to sink in. It meant no more oxygen use at 15 m/50 ft, which had been something the Navy got away with because their divers were in a transfer capsule going to a ship-born habitat.

“I would,” he went on, “use O2 at 6 m/20 ft and up for enhanced safety, if I was going to do something like that.” At that point, John had to return to Panama City for work. But he had planted an idea.

We immediately drove to Jacksonville where we tracked down the Air Products plant and, when they opened on Monday, we explained to the plant manager that we wanted him to make up a special gas mix for us. And, in those more innocent and frontier days, he said, “Sure.”

Later that week we were back at Diepolder II. We had even arranged for Dale Sweet to be our safety diver, although he was on air. Parker and I dropped down to 85 m/280 ft, and we concluded the dive without incident. The following Sunday we were back at the Wakulla Springs lodge restaurant and Zumrick again came over to join us. I casually said, “We went back to Diepolders, down to 85 m, and were totally clear headed.” Without a second’s hesitation Zumrick said, “Bullshit!“

Then I added, “On helium.” Those two words initiated a two-hour interrogation from Dr. Zumrick, Captain USN, on every detail of the dive and gas mixtures. John’s advice had opened the doorway to helium cave diving, and only the later involvement of Dr. Bill Hamilton (whose DCAP-based multi-gas decompression approaches were used during the Wakulla 1 project in 1987) was to have a comparable impact.

John Zumrick continued to be an important part of the Florida and Yucatan cave diving community throughout the 1990s, and he was one of the first to dive a dual Cis Mk5 rebreather during the 1999 Wakulla 2 project. For several decades, he served on the board of directors of the U.S. Deep Caving Team. But to me, John’s most important contribution to the diving world was neither his long professional service to the Navy, nor his later contribution as an anesthesiologist, but his being at the right place at the right time and imparting his wisdom regarding rebreathers and helium. It was his spark that lit the fire of the technical diving revolution.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Let There be Mix! by Simon Pridmore

inDEPTH: Celebrating Sheck Exley by Ned Deloach et al

InDEPTH:The First Helium-based Mix Dives Conducted by Pre-Tech Explorers (1967-1988) by Christopher Werner.

InDEPTH: The Early Days of Technical Trimix Diving Reports by Michael Menduno and Dr. RW Bill Hamilton

InDEPTH: Stoned: The Adventures of Wes Skiles and the US Deep Caving Team by William Stone

William C. “Bill” Stone, PhD, P.E. is the CEO of Stone Aerospace, Inc. and Sunfish, Inc., both based in Del Valle, TX. He is an internationally acclaimed cave explorer and the president of the United States Deep Caving Team.