Latest Features

The Early Days of Science Diving

Scientific diving veteran Bill High, founder of Professional Scuba Inspectors (PSI), recounts the origins of scientific diving in the US, and the development of early operational and safety guidelines for science divers as well as their role in undersea research.

By Bill High. Photos courtesy of Bill High unless noted.

The recent article in InDEPTH, “How I Became A Scientific Diver,” by Jenn Thomson, raises the question, “what is a scientific diver?” Interestingly, that question arose more than 70 years ago when the first scuba systems arrived at Scripps Institute of Oceanography. It was only shortly later that various aquatic research entities also gained access to “inner space” using scuba and similar devices. As you may know, I was a “science diver” beginning in 1955 and until 2015.

From the late 1950s into the early 1960s there was a rapid increase in the number of aquatic researchers along with too many people who considered diving unnecessary. I lectured at numerous fisheries conferences about the usefulness of scuba and conducted diver training for regional agencies.

Perhaps the best example of the disbelievers was the University of Washington school of Oceanography Director. In the early 1960s I hosted Capt. Couteau with his film “World Without Sun,” in Seattle. I invited the good doctor to a Cousteau reception. He quickly advised me that scuba diving was only an excuse to go play since all needed ocean data could be acquired by deploying instruments from a vessel.

The Origins in the US

Scuba diving in support of research projects was well underway in the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries (BCF) Florida lab by 1956 under the leadership of engineer Richard McNeely. He then established a science dive team at the Seattle BCF Lab in 1958. I joined that team in 1963.

The BCF needed rules, so a non-diving administrator in Washington D.C. wrote a set of science diving regulations for national fisheries. Those rules included no night diving, leaving the water in the presence of marine mammals,” and other nonsensical directives.

In 1969, the National Marine Fisheries Service named me its National Diving Officer. With guidance from Jim Stewart at Scripps, I wrote the first science diver operating rules for that agency which, by then, had numerous science diving teams throughout the nation.

Those rules were in force until the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was created in 1970. NOAA’s underwater work was put in the hands of its Manned Undersea Science and Technology office (MUST). I was named its National Diving Coordinator. New operating rules were implemented to keep OSHA out of our hair. Because of my extensive association with the sport diving community, the Director asked me how the MUST office could become more closely associated with all civilian diving.

Since we were, at that time, rather bound by the diving guidelines (and rules) in the US Navy Diving Manual, I urged him to establish an operational and safety manual for science divers that could also be used by the entire civilian dive community. Bob Dill and I put a plan together and had it approved, thus creating the NOAA Diving Manual that was published in 1975. That dive operational and safety manual has served the worldwide dive community for many years now.

Now it seems we need to define what a science diver is and whether there are other people who go underwater and see or do things that might represent a contribution to undersea knowledge.

What’s in Α Νame?

A great example of why science divers and commercial divers are very different occurred in 1975 when NOAA brought the German undersea habitat Helgoland to the offshore waters of Rockport, Massachusetts. Science divers and the commercial divers who operated the system dove together during setup dives. The NOAA divers dove conventional scuba while the German divers, also on scuba, were required to be tethered to the surface. Those divers became so entangled in the numerous lines and cables surrounding the habitat they could not readily follow the free-swimming science diver to accomplish the work. More importantly they would have been hindered trying to assist a buddy diver in an emergency.

A science diver (scientist diver) should be formally trained in some discipline. We likely should not define just what those disciplines must be as probably every professionally trained person has effectively used some form of underwater study.

I am sure we can find thousands of examples of the average recreational scuba diver seeing something of merit. I have several times asked local divers to “keep and eye out” for some objective. Such people are clearly valuable and should at least be science observers.

There is a need to identify those underwater science-related workers who carry out a vast array of work with the science diver. They are essential to most underwater studies. Can we call them science technicians? I would be very cautious about having some international group make science diving rules that could then be applied to all.

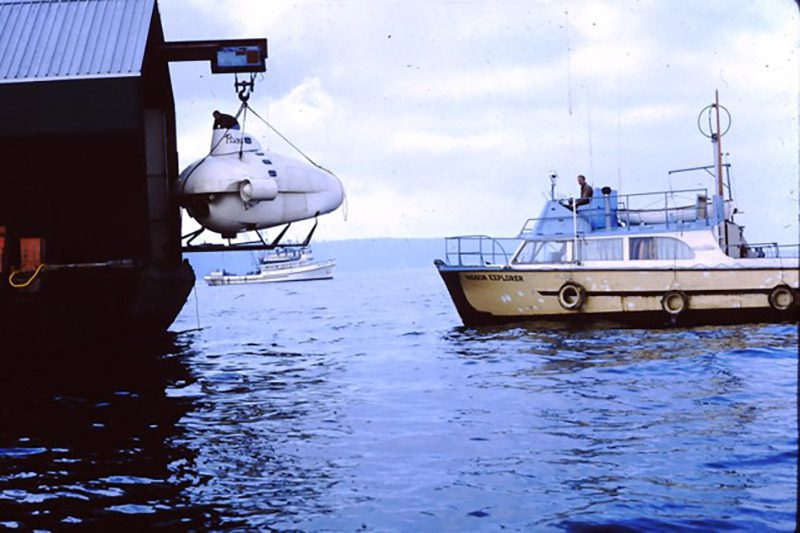

For people interested in learning how one highly experienced science diving team conducted a wide range of research diving projects they might want to read a report I prepared in 1993 just prior to my retirement from 36 years of science diving. The 47-page illustrated report is titled Observations of a Science/Diver on Fishing Technology and Fisheries Biology, draws upon both my personal and professional recollections, diving logs, informal and formal reports, and, where possible, interviews with former members of the NMFS SCUBA, undersea habitat and submersible dive teams.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH:A Brief History of Scuba’s Ubiquitous Aluminum 80 Cylinder by William (Bill) High

William (Bill) High. Bill began diving in 1955. He joined NAUI as instructor 175 in 1961. Throughout his career as a Fisheries Research Biologist he utilized scuba, undersea habitats, and deep submersibles to conduct fisheries research. Bill served as NOAA’s first National Diving Officer and was a U.S. representative to a United Nations committee. Bill saw the need for a practical cylinder inspection program when all too many cylinders failed explosively. He founded the Professional Scuba Inspectors Company in 1983. By 1990, PSI cylinder safety training became the standard for a wide range of cylinder types.