Cave

Laying Line in Ox Bel Ha

If you thought that the Riviera Maya had given up most of her secrets, think again. Underground expats Emőke Wagner, László Cseh, and Bjarne Knudsen managed to lay 20.3km/12.6 miles of new exploration line at Yax Chen, which is part of the Ox Bel Ha system. Here’s how they did it.

By Emőke Wagner, László Cseh and Bjarne Knudsen

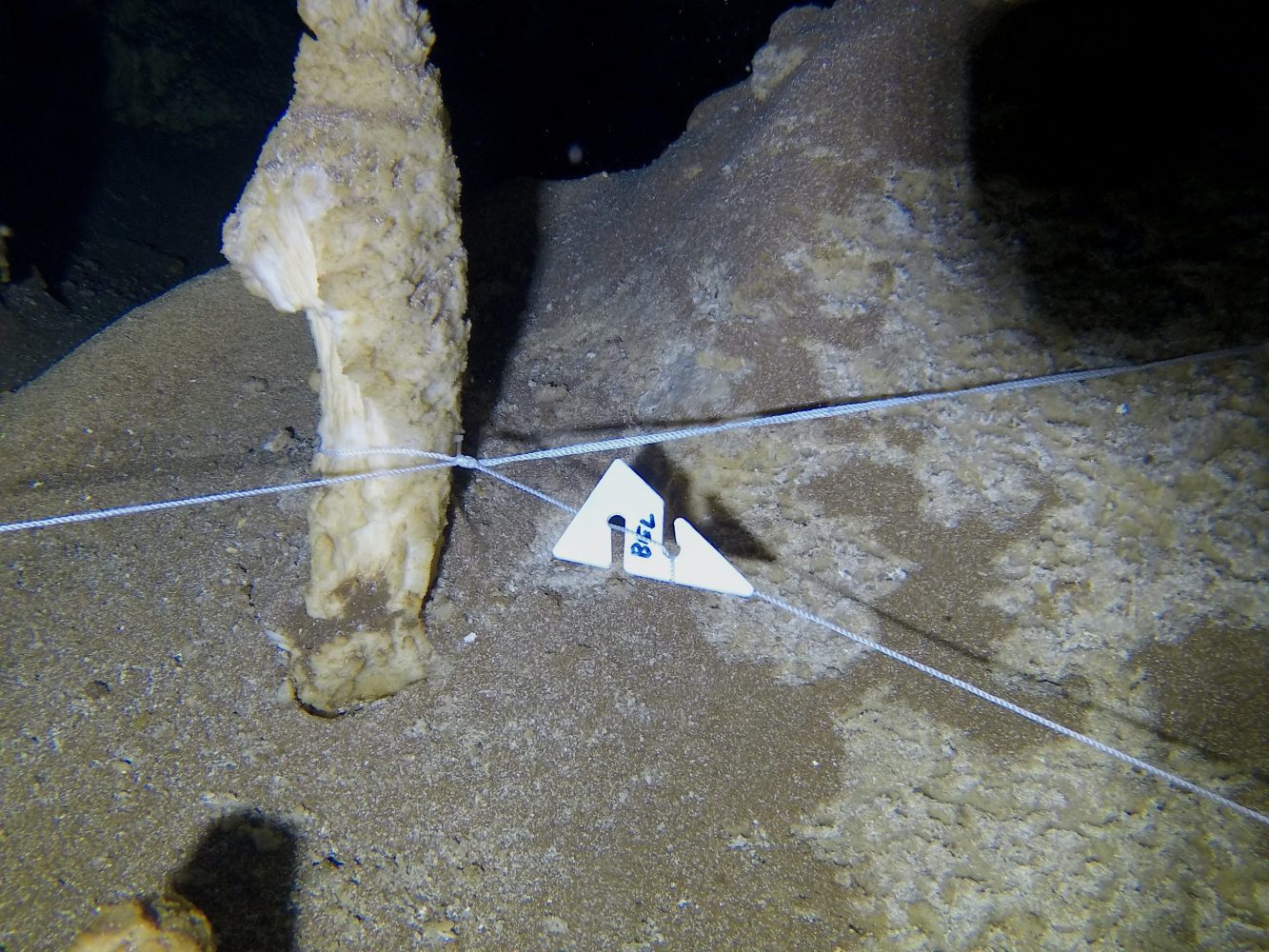

Header image: Permanent intersection at the ‘Los Pantanos’ area. Photo by Laszlo Cseh

Ox Bel Ha is the second largest underwater cave system in the world. Although it has been actively explored since 1998 by different groups of divers, the cave is steadily growing, new areas are discovered every year, and the exploration process seems unlikely to end anytime soon. Ox Bel Ha is a Mayan phrase meaning “three paths of water,” as the system expels water into the Caribbean Sea via three distinct underwater vents. The system is located southwest of Tulum in Quintana Roo, Mexico and extends southwest almost all the way to the Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve; a connection to the Reserve has not yet been found.

The COVID pandemic impacted Mexico, but after the local lockdown was lifted last year, our dive team decided to seek out new areas in the system and potential cave exploration. There were only the three of us: Emőke and László, (originally from Hungary but living in Mexico for some years, active GUE cave instructors) and our dear friend Bjarne from Denmark (GUE cave diver and previous WKPP member). Facing access issues immediately after quarantine, our team chose a cenote called Yax Chen (“blue or green well”) which seemed to be open to divers as if there were no pandemic at all.

Thanks to our participation in earlier projects, we had some idea of the cave’s structure, but we’re talking about a massive section of the cave that ventures many kilometers inland, where it adds 10 km/6.2 miles of different sections to its main tunnel. It also features a lesser known and less extensive downstream section, so just getting to a new cave in an area like this can be quite a challenge.

Yax Chen was first explored in 1997 by a couple, Kay and Gary Walten, who established most of the known lines both upstream and downstream of the cenote and made incredible penetrations, especially considering the diving technology available at the time. A few years later, a group of GUE divers called the Mexican Cave Exploration Project (MCEP) continued the exploration of the area, established the connection to Cenote Far, and discovered sections like Arizona, Little Chen, and more. In 2004, Bil Phillips and Steve Bogaerts connected Yax Chen to the Ox Bel Ha cave system.

Since Ox Bel Ha is a giant cave system, we decided—as always—to resurvey all existing lines, which was going to be interesting since our team had no data from the area. After a few months of survey in the early fall of 2020, we observed a lead-like opening from a more than 10-year-old line on one of our upstream survey dives; but, from our side of the tunnel, the lead looked like it hit a wall so, after swimming closer, we turned away immediately since it was too small for us to fit.

A few days later, when we came back to almost the same spot, we were still thinking about the lead, so we decided to take another look at it. This time, instead of swimming straight to the small opening, we swam along the wall, and as we got closer, the wall turned out to be deceptive. It was more like a huge boulder that had fallen, but it had a decently sized opening on its right side. After one right turn followed by one left, the cave started to open up into a bigger collapsed room. We swam under a ledge, where the water seemed to come from, and we hit the halocline at the same time. After a 100-150 m/328-492 ft swim, the tunnel became more defined and opened up into 10-15 m/33-49 ft wide rooms with a floor to ceiling distance of 3-4 m/10-13 ft. We ran out of line quickly, knowing we had some cool exploration ahead but having no clue that this discovery would establish a new 20.3 km/12.6 mile section of the system!

Finding New Paths

We subsequently conducted follow on dives from the newly established tunnel, located about 2 km/1 mile upstream from our entry point. We explored the cave further upstream, while documenting side tunnels and checking out other interesting leads. With the advent of electronic survey tools like Mnemo, using unknotted lines in the cave became more prevalent in local cave exploration. In the beginning of our journey, with limited access to such survey tools, we decided on using knotted lines overhead as a back up in the event of device failure. Even later in the project, when we had more access to electronic tools, we resolved to keep putting the knotted line on our reels, since it could eventually be useful in creating a more detailed map of the cave.

Directional markers in the newly explored area have been labeled “BEL” to represent our first initials, and “Bel” in Mayan translates to “path.” It’s very fitting, since the three of us were trying to find new paths in the cave every day.

During one of our early upstream dives in our steadily growing new area, we bumped into an existing downstream line and found a new connection between the upstream and the downstream sections of Yax Chen. After this discovery, the team decided to focus on the upstream area of the cave, continuing further northwest.

At this point, we already had a few kilometers of cave exploration experience in other parts of the cave, but we very quickly learned that cave exploration, especially in this part of the system, was not easy. On each dive, we got progressively further from our nearest entrance. The system is very complex, it has a lot of sediment, and the tunnels don’t remain wide over long distances. We can’t count on our fingers the number of times we thought the exploration was over, decided to do one more dive, and pushed through a nasty and tight restriction to find a few more kilometers of cave.

As the upstream dives extended to the northwest, the cave started to drop below halocline level, which in this area isn’t a good sign. The tunnels were amazingly beautiful, full of decorations and deep blue water, but as we continued northwest, the flow seemed to stop and the tunnels narrowed. Luckily, one freshwater lead remained to the northeast—a difficult one, due to its small size and the amount of sediment—but, after navigating it and passing a smaller tannic room, the cave opened up again. This side of the cave led to another bypass area, then to the previously discovered saltwater section, which allowed passage for more gear in order to get further.

Penetrating further north from the new lines, we found irregular and small freshwater tunnels, but farther upstream they all hit a massive collapse. One tunnel at halocline level continued past a sidemount restriction, but this one also ended, dropping down into the saltwater.

As we were wrapping up the final leads on the new upstream area, the total new distance explored stood at 10 km/6 miles. One remaining lead dropped back into the saltwater, but this time the cave looked different. The walls of the cave were much darker. Light brown, easily disturbed sediment covered everything. Passing through a new sidemount restriction, the cave opened up into a very defined and wide tunnel leading to one of the biggest rooms we have ever seen underground in a wet cave in Mexico. Some parts of it were in the freshwater and some still down in the saltwater, and it was highly decorated with cave formations.

It’s About the Connections

The saltwater tunnel leading to the room had some animal bone remains, most likely belonging to some kind of bird. On the other side of the room, we dropped down into a decent-sized tunnel that started to turn downstream. We reviewed our survey upon returning home, deciding that traveling downstream from our main entrance could possibly provide a connection to new big room and, if we were lucky enough to find a new route, it could be shorter (1.5 km/0.9 miles instead of 2 km/1.25 miles) and potentially easier than our current route. During two dives from downstream Yax Chen, we found the end of line from our previous exploration and the team discovered two new cenotes along the way. We named them Yax Ich which means “green eye,” and the other K’aas Naay, or “bad dream.” This established one upstream and one downstream connection of the Yax Chen area. Fortunately, this connection proved to be easier to travel and more leads were waiting for us. We found old exploration lines within about 500 m/0.3 miles of our newly discovered big room.

For quite some time, no one had made new connections between the historic area of Ox Bel Ha and Yax Chen, so we have decided to travel northeast to determine if we can make it all the way to the historic Ox Bel Ha. The dives turned out to be maze-like and heavily silty, but we dived two nicely decorated, complex freshwater tunnels, where one ended in a tannic collapse and the other had a challenging sidemount tunnel which we named the “Wormhole.” Although this tunnel was well defined, it still had enough small holes to make it difficult to choose which one to peek into, but the constant flow justified the effort. It took some dives to take the line further, but the cave finally opened up again.

From this point, we were sure we could connect to Ox Bel Ha, since the big open tunnels pointed straight toward the historic section (which perhaps hadn’t been visited since 1999). Some of the tunnels had traces of charcoal and remains of unidentified animal bones. After some struggles, we made our first connection through a very difficult, low-ceilinged, muddy tunnel. Later, just by accident, we bumped into the old line five more times as we explored leads to the north. As we started to get boxed in by the historic lines, and acquiesced to the salt water that “killed” our tunnels on the west side, we realized that all good things—this amazing, laborious experience included—must come to an end.

To wrap up the remaining leads, we organized three consecutive days of exploration, bringing our project’s total underwater time to 21 hours. Almost the entire exploration took place underneath a swampy wetland area and, as a result, some parts of the cave were often filled with tannic water. We named this new section of the cave “The Swampland” or “Los Pantanos” in Spanish.

Today’s generation of explorers needs to examine the environment differently than the cave’s original trailblazers. The standardized methods of team diving and the excellent training we received from GUE helped us overcome these difficulties, but without access to high-quality gear, this project wouldn’t have been possible. Fortunately, we were able to alternate between a back mounted and sidemount tank configurations as needed and to develop systematic methods of transporting a lot of equipment even further into the cave.

We would like to express our thanks to Dr. Mario Valotta for his support with our dive gear; a very special thanks to GUE instructor trainer Daniel Riordan for joining us for one very productive day of exploration.

Additional resources:

InDepth: Data for Divers: Mexican Explorers Go Digital to Chart Riviera Maya

InDepth: They Discovered an 11,000-year-old Submerged Ochre Mine

Emőke Wagner is originally from Hungary and began diving at a young age. She has been an active instructor since 2014. After a couple of years spent traveling around the globe, she moved to Mexico with her husband in 2017. While living in Mexico, cave diving became her real passion, and she began exploring more of the local cave systems. Since 2016, Emőke has been working as a full-time GUE instructor and is currently teaching the cave, foundational, and recreational curriculum.

László Cseh is from Hungary and has always been fascinated with the underwater world. He became a recreational diving instructor in 2012 and began teaching and traveling with his wife, Emőke. After becoming a GUE instructor in 2016, he moved to Mexico to look for new diving challenges. Local cave exploration possibilities helped him achieve his GUE Cave instructor certification.

Bjarne Knudsen began diving in 1993, taking his first tech classes in 1997 and his first GUE Cave and Tech classes in 1999, so has been part of the GUE community since the early days. In the early 2000s, he spent some years in Florida, where he was a part of the WKPP. During this time, he also pushed Sheck Exley’s end of line in the Cathedral Cave system with Todd Leonard (and lots of support from friends). Bjarne is currently on a slow world cruise with his wife on their sailboat. For the last few years, they’ve been a little stuck in Mexico and the surrounding countries, which offer so much nice diving.

Categories: Exploration, Latest Features, Cave Diving,

Tags: V 3.6, Cave diving, Ox Bel Ha, GUE project, Exploration