Exploration

La Grande Dérive

Tech diving brothers Marc-André and Pierre-Olivier Dubois report on their exploration of the St Lawrence River and its shipwrecks in a traverse of over 12.5 km, connecting the A.E. Vickery, The Oconto, The Sir Robert Peel, Roy A. Jodrey, and the Islander. What do you do when there is no dive charter available? Grab your rebreather and your two favorite DPVs and prepare yourself for a 7-hour ride.

A traverse of over 12.5 km connecting some of the St. Lawrence River’s most famous shipwrecks

By Marc-André Dubois and Pierre-Olivier Dubois. Lead image: Setting up the gear required for their seven-hour traverse.

As young divers, my brother and I used to explore the waters of the St. Lawrence River as often as we could, looking for lost vintage bottles half buried in the zebra mussels. These artifacts, remnants of another era, were to us witnesses of the relentless passage of time. From old bottles, we later switched our attention to shipwrecks and started exploring the underwater landscapes of the Great Lakes and their rich maritime history. The numerous wrecks in these waters, victims of the tricky maritime passages and the unforgiving weather of the region, became our museums.

The transition to technical diving gave us the abilities needed to push our boundaries farther, ultimately leading us to explore uncharted underwater territories. Questions like “would it be feasible to reach these dive sites from shore?” and “would it be reasonable to leverage our knowledge in bathymetry and hydrology dynamics to reach these remote and difficult to navigate destinations without a compass?” began to be part of our diving discussions. The use of closed-circuit rebreathers (CCR) and diver propulsion vehicles (DPVs) allowed us to assess these concepts to the point where it became more exciting to dive from shore and navigate underwater than to enjoy the comfort of a dive charter.

That’s when we realized that the shipwrecks we used to visit from shore were naturally aligned along a narrow path, like an already solved version of the “traveling salesman problem”. We came to the conclusion that reaching all these points of interest in a single dive could certainly be feasible. We decided to call the expedition La grande dérive, a French reference to the vintage amusement parks, considering this traverse would certainly be comparable to riding in a roller coaster for a couple of hours.

The idea was quite simple: by accessing the river from a small public park upstream of our targets, we would navigate following a route that connects five famous wrecks of Thousand Islands, namely the A.E. Vickery, the Oconto, the Sir Robert Peel, the Roy A. Jodrey, and the Islander, and resurface at our hotel in Alexandria Bay, covering a distance of nearly 13 km/8 mi in a single dive and without surface support. The dive notably involved crossing the waterway twice: at first in 50 m/164 ft of water between the Vickery and the Oconto, and then on a second occasion near the stern of the Jodrey at a depth of 60 m/197 ft, in total darkness and fighting strong lateral currents.

1. A. E. Vickery

Launched in 1861 under the name J.B. Penfield, the vessel that would become the A.E. Vickery sank in 1889 at a depth of 35 m/115 ft after striking a shoal. The wreck, now fully penetrable, served as the starting point of our traverse.

2. Oconto

During its inaugural voyage in 1886, the Oconto steamer struck a shoal. After an unsuccessful salvage attempt, the vessel slipped into the waters of the St. Lawrence, breaking in two during its descent to end its journey in 55 m/180 ft of water, across the waterway.

3. Sir Robert Peel

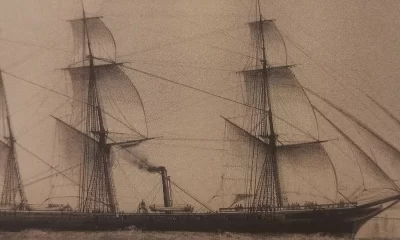

Upstream from the bridge connecting Wellesley Island to Alexandria Bay now lies the remains of the ship Sir Robert Peel in 40 m/131 ft of water. Commissioned in 1838 under the supervision of Captain John B. Armstrong, the Sir Robert Peel was heading toward Toronto with 19 passengers aboard. They were also carrying the paycheck of the Upper Canada military troops. The ship was intercepted by the pirate Bill Johnston, who, in his failed attempt to use the vessel to transport rebel troops to Canada, ended up setting the ship on fire, shouting, “Remember the Caroline” in reference to the Patriot war.

4. Roy A. Jodrey

Undoubtedly the queen of these waters, the wreck of the Roy A. Jodrey is one of the largest wrecks in the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, measuring 195 m/640 ft long by 22 m/72 ft wide. Sank in 1975 as a result of damage caused by a collision with a maritime buoy, the Roy A. Jodrey now lies at depths ranging from 45 to 70 m/148 to 230 ft broken in two and resting on its side, hanging on the edge of Wellesley Island. The strong currents, the size of the wreck, and the occasional low visibility are all elements that add to the challenge of visiting it.

5. Islander

Originally used to provide mail service between Clayton and Alexandria Bay, the Islander was later converted by the Thousand Islands tourist industry in 1893. While docked, it sank in 15 m/50 ft of water following a violent fire. It now lies in a calm bay, which proved to be an ideal refuge for our upcoming decompression.

The challenge promised to be interesting: as the river is subject to winds and influenced by the hydroelectric facilities of the region, it is common to see abrupt changes in diving conditions in these waters. Visibility can thus go from over 25 m/82 ft to less than 5 m/16 ft without warning. The currents can also be unpredictable; during exploration dives, we witnessed downwelling currents so strong that they were vertically ripping the zebra mussels from their firm anchors in the rocks in a scene looking like an underwater waterfall of shells disappearing into the abyss.

The Plan

Although our traverse would not be considered as an overhead dive (beside the usual decompression obligations) as is the case in cave diving, the unique conditions of the St. Lawrence River would greatly limit our ability to safely resurface in case of a problem. In fact, every year, in addition to the recreational boating activity and the touristic industry, over 35 million tons of raw products are transported on this river, which can be less than 100 m/328 ft wide at its narrowest point (which was obviously a part of our itinerary) and is punctuated by islands of all shapes. Adding to the fact that these waters are subject to variable, unpredictable currents of high intensity, it became evident that surfacing in the middle of the seaway was not only impractical, but could also pose serious concerns for our safety as it would be a major inconvenience to the maritime traffic.

So, to mitigate the risks of an emergency ascent in open water, we identified areas on either side of the river that, while they would not constitute ideal exit points under normal circumstances, could at least serve as shelter in case of an emergency. We divided the route into different sections and identified the zones designated for safe ascent in the event of an emergency, and during preparation dives we placed underwater markers to guide us. The same strategy was also used to identify other critical timing points of our dive.

Considering the wrecks we wanted to reach, it was not feasible to remain at constant depth for the entire duration of the traverse, so we installed these markers to reassure us of the correct timing for the various descents. This profile led us to ask the central question of any deep dive: how to manage decompression in the context of such a long immersion? Fortunately, given the distance we had to cover, the answer became apparent on its own.

Let’s say someone wants to do a typical deep wreck dive in the range of 60 m/197 ft, stay there for 20 minutes, and then go back to surface. The diver will obviously have to follow a decompression schedule in order to control desaturation and avoid decompression sickness. Now, if this person, instead of trying to reach the next decompression ceiling, stays at a relatively shallow depth (for example 21 meters) for an extended period of time, the in-gassing dynamics will continue up until saturation of the body tissues. Thus, the question one needs to answer in order to consider a profile like that would be: what would be the time penalty for that additional time spent in shallow waters?

It turns out that for the typical profile mentioned earlier, the penalty is relatively minimal. In fact, for a duration between 90 min and 420 min of time spent at 21 m/70 ft, the additional decompression increases relatively linearly, adding roughly 8 minutes every additional hour of diving. The other good news is that this additional time will be spent near the surface, when the luminosity and the temperature are more adequate. For us, these details were the key for our traverse. Having to consider a small decompression penalty in exchange for a big exploration dive was a compromise we could easily accept. Putting everything together, we anticipated staying underwater for a total of about 7 hours.

The traverse

When all the different pieces were stitched together, there was only one remaining thing for us to do. On a cold and sunny day at the end of October, we strategically parked a car near our destination, and drove another one with all our gear to the small park of Reed Point. We then started the pre-dive inspection, validation of every aspect of the dive. While preparing our gear, we caught the attention of the nearby residents. An elderly gentleman, wanting to start the conversation, informed us about a supposedly shipwreck not far from our launch point. His smile quickly faded when we mentioned that we would not only reach his wreck (the Vickery), but four other ones as well and we would surface in another town, where the moon would be the sole source of natural light.

We started our journey with the usual grace of a super loaded technical diver, walking miserably the first couple of meters on the beach as the water level was unusually low for the season. Firing up our scooters, we reached the A.E. Vickery 30 minutes into the dive. We took advantage of the accessibility and protection from the elements of the inside of the wreck to validate the working order of our equipment. From the stern of the Vickery, we went directly across the channel, at full speed and were carried away by the current. Ten minutes later, the Oconto was showing its sinister shape, contrasting with the faded residual ambient light.

As would be the case at various other predefined moments during this dive, leaving the Oconto was for us the occasion to rearrange the group formation. During our preparation dives, we found that switching the leader from time to time gave the opportunity to the new follower to relax a bit and enjoy the ride while ensuring a more homogeneous drain of the scooter, as the leader usually consumes less battery during long rides. We evaluated that 20 minutes represented a good switching point and we tried to follow this schedule as much as possible.

Leaving the Oconto, it was time to make our first ascent of the dive and, with that in mind, we initiated our decompression while continuing the drift, flying beside the massive rock formations. At two hours of running time, we saw our red marker, signaling that we needed to start our descent for the Sir Robert Peel. We took the opportunity to rest and while waiting, my brother decided to inspect our marker. While he found the integrity of the line to be immaculate, he also cut his left dry glove straight open on a sharp zebra mussel. From that point, amongst all the things that he needed to manage, he would also have to deal with the water that would gradually find its way inside his drysuit. Thankfully, the water was still relatively warm at that time of the year, and the risk of hypothermia was minimal even considering the five hours that were still in front of us.

The Robert Peel was an important milestone, as it marked a point of no-return, beyond which the underwater shelter provided by the bathymetry of the shore near Wellesley Bridge would be difficult to reach. Past that point, the next exit was far away, and it was a long joy ride in the 21-meter zone. Our main objective during this part of the traverse was to identify as early as possible the various bays standing between us and the Roy A. Jodrey in order to avoid them. Having an extensive knowledge of the bathymetry of these bays, and a detailed list of compass headings helped us to navigate in these conditions. At roughly four hours of running time, we took advantage of the calm of one of these bays to fire our second scooter. At that moment, we still had around half a charge left in our first one. By switching at that moment, we would still have a good backup in the event of a failure, while having a fully charged scooter to tackle what was waiting ahead of us.

When we hit 4 h 30 min of runtime, we started to consider that the blue marker we had previously installed for the Jodrey was probably gone or that we had missed it. Fortunately, after slowing the pace, we were able to recognize the main line connecting the wreck to the bay used by boat charters. We then started our descent to access the bow of the wreck at 65 m/213 ft. It took us about 10 minutes to scooter the Jodrey from the bow to the stern at maximum velocity with the current pushing us further. As we rushed our way to the stern, one of the bailout’s second stages made close contact with a hidden railing and snapped right off, in an explosion of gas. We were able to manage the problem quickly and continue our drift without further issues. It seems that from time to time, some shipwrecks enjoy the company of divers so much that they want to keep a souvenir of their visitors!

Arriving at the propeller of the Jodrey, we then had to cross the seaway once again, trying to reach Cherry Island. Having done the Jodrey from shore a couple of times, we already knew the ride could be a little choppy. This dive was no exception. Pushed by the current, our crossing of the channel was a bit like playing dodgeball with massive rock boulders in complete darkness. In addition to those conditions, we were now relying on a team bailout configuration which made this traverse even more dreadful.

Back on the mainland side of the river, it was then time to start our final ascent and decompression. We continued our way, following the contours of the seaway, and we reached the Islander after 5 h 30 min of runtime. This last wreck appeared to us like the comforting light of a hotel after a long ride on the highway, and we thus took some time to relax and enjoy the decompression. We finally emerged from the water on the little beach of the Bonnie Castle Resort in the dark of the night, 6 h 47 min after our sunny immersion in Reed Point.

In the end, this traverse gave us a new perspective on some of the hidden features of the Thousand Islands. While diving, we had the opportunity to witness not only the forces of nature, but to recognize our resilience as well. Executing this dive without surface support certainly added a level of complexity to the expedition. Indeed, there is a real need for commitment when you rely exclusively on yourself in the event that something goes bad. But this comes with a rewarding feeling of freedom and accomplishment that cannot be beaten, that ultimately fuels our desire to explore these underwater regions even further.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: The Devil In Your Dive: My 70-km Traverse of the St. Lawrence River by Nathalie Lasselin (2021)

InDEPTH: Diving Rocks! The Traverse from Ship Rock to Bird Rock by Francesco Cameli (2021)

ResearchGate: Dive Logistics of the Turner to Wakulla Cave Traverse by Dawn Kernagis and Todd Kincaid (2008).

Being part of a family of divers, Marc-André and Pierre-Olivier have been diving in the Great Lakes and all over the East Coast for more than 23 years. Marc-André is a lead scientist at the Hydro-Québec Research Center and Pierre-Olivier works as a robotics engineer for the Canadian Space Agency. By combining their unique scientific skills to technical diving, they push underwater exploration further. They can be reached at: ma.dubois@me.com, and Pierre-Olivier.dubois@hotmail.com. Find them on Instagram at: @marcandre.dubois, and @p.o.dubois