Latest Features

Isobaric Counterdiffusion in the Real World

Isobaric counterdiffusion is one of those geeky, esoteric subjects that some tech programs deem of minor relevance, while others regard it as a distinct operational concern. Divers Alert Network’s Reilly Fogarty examines the physiological underpinnings of ICD, some of the key research behind it, and discusses its application to tech diving.

By Reilly Fogarty

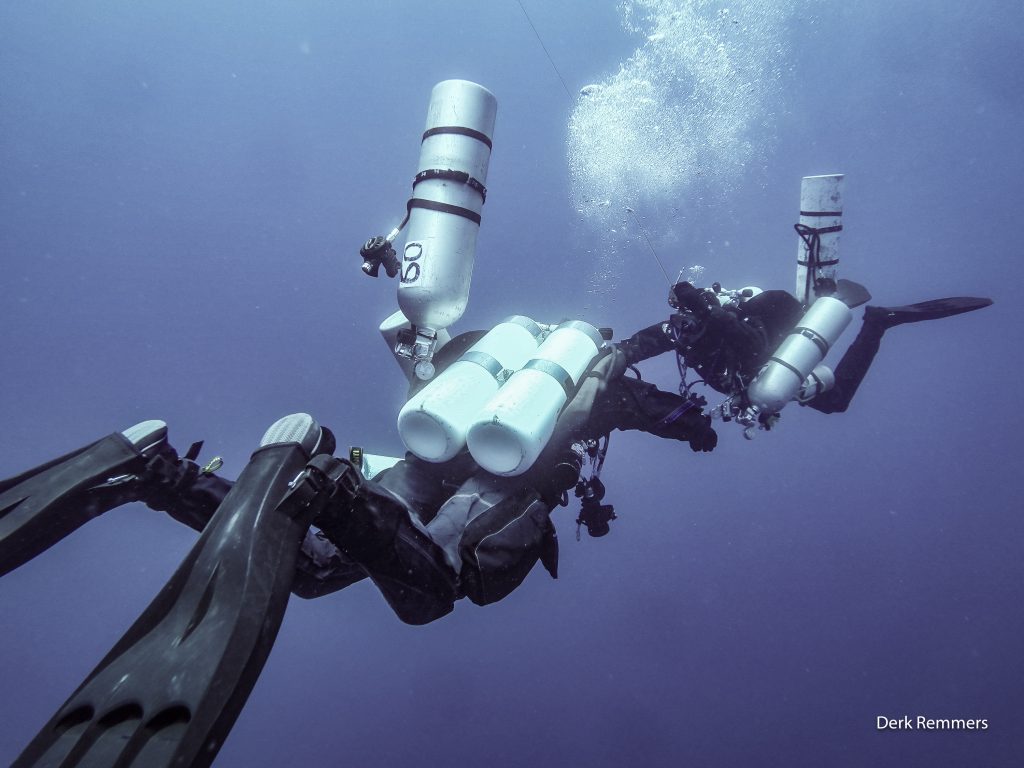

Header image by Derk Remmers

Most divers don’t spend much time thinking about isobaric counter diffusion (ICD), and it’s not just because it has an inconveniently long name. The phenomenon is complicated to understand, depends on mechanisms that are partially or wholly theoretical, and falls squarely in the unknown gray area of decompression science. As a result, students in technical courses receive varying information about the subject, depending on their instructor’s understanding of it.

Some consider the topic irrelevant to divers while others recognize that a functional understanding is mandatory for modern mixed-gas diving. A combination of infrequent exposure, lack of research and widely spread misinformation have made ICD an unapproachable subject for many divers. Here’s what we know and what we’re still researching.

The Physiology

Isobaric counterdiffusion is not a concept that’s limited to diving. The phenomenon describes the diffusion of different gases into and out of tissues after a change in gas composition and the physiological effects of those gas switches. This is relevant in hyperbarics, anesthesia and diving and aerospace. As divers we’re most concerned with what happens with a gas switch during a mixed-gas dive, and research in related fields can provide useful data.

The effects of ICD as they relate to divers primarily involve the movement of two inert gases in opposite directions at equal ambient pressures, hence the term “isobaric,” in tissues and blood. The relative speeds of counterdiffusion are affected by many factors including density, surface tension and viscosity in fluids, as well as a variety of physiological factors, membrane properties and specific gas interactions (Oswaldo, 2017). Gas diffusion itself is a fascinating and broad topic but one for another day, so for the sake of understanding ICD it can be simplified somewhat. Fundamentally the issues related to ICD center around a disparity in the speed at which one inert gas diffuses into the body while another diffuses out. This can occur with a slow saturated gas exiting a tissue and a fast saturating gas entering or vice versa.

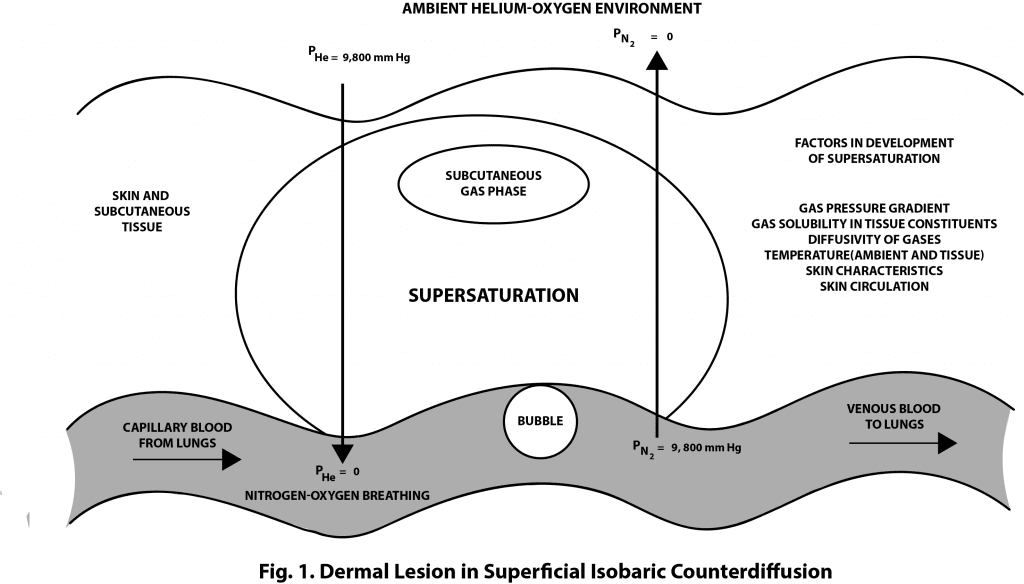

Superficial ICD occurs when the inert gas breathed by a diver diffuses more slowly into the body than the gas surrounding the body. Because this requires being surrounded by a gas with a high diffusivity it is most often seen in saturation divers breathing air or a low-helium content gas in a heliox environment. This can theoretically occur in diving and is the reason that new mixed-gas divers are told to avoid using a suit-inflation gas containing helium (besides that fact that it has low thermal conductivity i.e. its cold!).

Helium has a diffusivity that’s approximately 2.65 times that of nitrogen (Lambertson, 1989), and because of that disparity it can diffuse into the skin quickly while nitrogen diffuses more slowly. The slow diffusion of nitrogen from the fluids and tissues of the body while the helium saturates the skin can cause supersaturation in some superficial tissues that can result in gas bubble formation. These gas bubbles can cause painful, red lesions on the skin, but the phenomenon does not occur when the gases are reversed and the breathing gas has a greater diffusivity.

If ICD is a concept you’ve encountered before it’s likely deep tissue ICD that you’ve been exposed to. This second type of ICD occurs when one breathing gas is exchanged for another of different diffusivity, as in a gas switch from say a nitrox travel gas to a trimix bottom mix or from a trimix bottom mix to a nitrox decompression gas. As with superficial ICD, this occurs when a gas with high diffusivity is transported into a tissue more rapidly than a slower-diffusing gas is transported out. The result is the same: supersaturation of some tissues and bubble formation. These bubbles can cause itching followed by joint pain and have been more recently associated with inner-ear decompression sickness, although the bubble formation could contribute to other types of decompression sickness as well.

The Research

Quantifying the risk of ICD and identifying cases of decompression sickness (DCS) that resulted from ICD rather than other risk factors can be difficult, but there is significant research correlating several proposed mechanisms to increased bubble counts and DCS in human and animal models. Like DCS, ICD is fairly well accepted academically on a correlational basis, but the specific mechanisms require additional research to confirm.

Data from as early as 1977 indicates a risk of ICD in divers even within recreational depths, with increased bubble counts observed in goats saturated at 5 atmospheres and switched from a breathing gas containing 4.7 atmospheres of nitrogen to 4.7 atmospheres of helium (D’Aoust, 2017). Similarly, saturation divers on the Hydra V mission experienced DCS following a gas switch from hydreliox to a faster-diffusing heliox mixture, with the gas switch thought to have caused the DCS (Rostain, 1987).

More recent work on decompression models of the inner ear have indicated that even a transient increase in gas tension (the relationship between breathing gas and gas saturated in the body) related to a switch from a high-helium-content gas to a nitrogen mix may increase the risk of inner-ear decompression sickness (IEDCS). This model is particularly interesting because the diffusion of gases across the round window is extremely low (bordering on negligible), which complicates the transport of inert gases in the ear. Data from Doolette and Mitchell suggests that these gas switches could result in a temporary increase in gas tension as the nitrogen input exceeds the removal of helium via perfusion in the vascular compartment and diffusion in the peri- and endolymph causing bubble formation and growth (Doolette, 2003).

There are several variables to consider with this model, but the data appears sound and the mechanism provides a likely explanation for the well-documented cases of IEDCS related to gas switching in technical diving. Other models have been proposed to explain these incidents, and these vary by physiological models and diffusion constants used, but most focus on tissue supersaturation as a result of varying gas tension following a gas switch (Burton, 2004).

Academic Versus Application

The challenge with the varied research into the mechanisms of ICD is that it can be difficult to determine what’s prudent to include in your dive planning and what data might not reflect reality. The good news is that the general aspects of ICD are fairly well understood, even if the specific mechanisms are theoretical. Reducing variances in gas diffusivity and transient tissue tension via conservative dive planning is relatively easy to do and poses no significant additional risk. Decompression obligations may be increased in some instances, but some mixed-gas courses are already including some ICD considerations, primarily related to IEDCS.

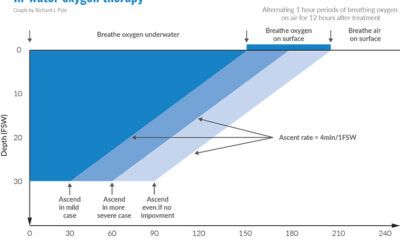

Extending this to minimize the risks associated with ICD is not complicated, but specific recommendations are unfortunately not readily apparent. Lambertson proposed that switching from a helium mixture to a nitrogen mixture would be acceptable but the reverse should include recompression — something unlikely to be an option during a dive charter. Doolette and Mitchell propose a more practical approach: minimizing the switch from trimix to nitrox on ascent or planning to perform these switches at depth or in shallow water to minimize supersaturation.

Doolette and Mitchell propose a more practical approach: minimizing the switch from trimix to nitrox on ascent or planning to perform these switches at depth or in shallow water to minimize supersaturation.

There are some specific recommendations for preventing ICD (using the rule of fifths, calculating theoretical helium and nitrogen compartments, etc.), but these lack evidence and may or may not prevent incidents. What we can say is that planning your gas switching to minimize supersaturation due to transient tissue tensions, minimizing your switches from high-helium-content gases to low (as appropriate for your acceptable risk levels), and increasing conservatism as depth and dive time increase (due to increased tissue saturation levels) are good ways to keep yourself safe.

The mechanisms may not yet be definite, but the data can back up these recommendations. And when there is no increase in risk with the conservative approach, it makes sense to go that route. Keep an eye on upcoming research in this area; while ICD can cause problems, some researchers are proposing that isobaric underdiffusion could decrease risk on technical dives, so it’s possible that your gas planning might be in for a shakeup in the near future.

References

- Oswaldo, C. Gas diffusion among bubbles and the DCS risk. (November 24, 2017)

- Lambertson, Christian J (1989). Relations of isobaric gas counterdiffusion and decompression gas lesion diseases. In Vann, RD. “The Physiological Basis of Decompression”. 38th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop UHMS Publication Number 75(Phys)6-1-89. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/6853.

- D’Aoust, B. G., Smith, K. H., Swanson, H. T., White, R., Harvey, C. A., Hunter, W. L., … Goad, R. F. (1977, August 26). Venous gas bubbles: production by transient, deep isobaric counterdiffusion of helium against nitrogen.

- Rostain, JC; Lemaire, C; Gardette-Chauffour, MC; Naquet, R (1987). Bove; Bachrach; Greenbaum (eds.). “Effect of the shift from hydrogen-helium-oxygen mixture to helium oxygen mixture during a 450 msw dive”. Underwater and Hyperbaric Physiology IX. Bethesda, MD, USA: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society.

- Doolette, David J; Mitchell, Simon J (June 2003). “Biophysical basis for inner ear decompression sickness”. Journal of Applied Physiology. 94 (6): 2145–50. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01090.2002. PMID 12562679.

- Burton, Steve (December 2004). “Isobaric Counter Diffusion”. ScubaEngineer.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Tale of Two Agencies: How two tech agencies address isobaric counterdiffusion by Daniel Millikovsky

Note: The British Sub Aqua Club (BSAC) recommends that divers allow for a maximum of 0.5 bar difference in PN2 at the point of the gas switch. According to former BSAC Tech lead Mike Rowley, “The recommendation isn’t an absolute but a flexible advisory value so a 0.7 bar differential isn’t going to bring the Sword of Damocles down on you.”

When he’s not working with DAN on safety programs, Reilly Fogarty can be found running technical charters and teaching rebreather diving in Gloucester, Mass. Reilly is a USCG licensed captain whose professional background includes surgical and wilderness emergency medicine as well as dive shop management.