Education

How Two Tech Agencies Address Isobaric Counterdiffusion

NAUI is one of the few training agencies that offers specific protocols to address Isobaric Counterdiffusion (ICD). Here NAUITEC Instructor Trainer and Examiner Daniel Millikovsky explains their approach to minimize ICD risks based on their Reduced Gradient Bubble Model (RGBM). GUE Instructor Trainer and Evaluator Richard Lundgren then explains GUE’s position on the subject. The gas diffuses both ways!

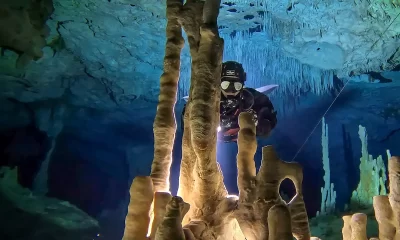

Header image by Derk Remmers

Not A Theory — A Fact! How NAUITEC Manages Isobaric Counter Diffusion

by Daniel Millikovsky

There is some confusion in the technical diving community as to whether we should pay attention to the physical law while planning gas switches, particularly on ascent. Here are some of the basics of this topic and how NAUI’s technical division, NAUITEC, has addressed this matter in training and diving operations since 1997.

Fact: Isobaric counterdiffusion is a real gas transport mechanism. We need to pay attention to it in mixed gas diving.

Fiction: Isobaric counterdiffusion is a theoretical laboratory concept and doesn’t affect divers at all.

From NAUI Technical Diver (textbook):

Isobaric counterdiffusion (ICD) describes a real gas transport mechanism in the blood and tissues of divers using helium and nitrogen. It’s not just some theoretical concoction, and it has important impacts for tech diving. It was first observed in the laboratory by Kunkle and Strauss in bubble experiments, is a basic physical law, was first studied by Lambertsen and Idicula in divers, has been extensively reported in medical and physiology journals, and is accepted by the deco science community worldwide.

Isobaric means “equal pressure.” Counterdiffusion means two or more gases diffusing in opposite directions. For divers, the gases concerned are the inert gases nitrogen and helium and not metabolic gases like oxygen, carbon dioxide, water vapor, or trace gases in the atmosphere. Specifically, ICD during mixed gas diving operations concerns the two inert gases moving in opposite directions under equal ambient pressure in tissues and blood. In order to understand this, we have to consider their relative diffusion speeds. Lighter gases diffuse faster than heavier gases. In fact, helium (He) is seven times lighter than nitrogen (N2) and diffuses 2.65 times faster.

If a diver has nitrogen-loaded tissue, and if their blood is loaded with helium, this will result in greater total gas loading because helium will diffuse into tissue and blood faster than nitrogen diffuses out, resulting in increased inert gas tensions. Conversely, if a diver has helium-loaded tissues, and their blood is loaded with nitrogen, this will produce the opposite effect: Helium will off-gas faster than nitrogen on-gases, and total inert gas tensions will be lower. This last case is what we can call in decompression planning a “Good ICD,” but we need to choose the fractions of N2 wisely on ascent.

Also, Doolette and Mitchell’s study of Inner Ear Decompression Sickness (IEDCS) shows that the inner ear may not be well-modelled by common (e.g. Bühlmann) algorithms. Doolette and Mitchell propose that a switch from a helium-rich mix to a nitrogen-rich mix, as is common in technical diving when switching from trimix to nitrox on ascent, may cause a transient supersaturation of inert gas within the inner ear and result in IEDCS. They suggest that breathing-gas switches from helium-rich to nitrogen-rich mixtures should be carefully scheduled either deep (with due consideration to nitrogen narcosis) or shallow to avoid the period of maximum supersaturation resulting from the decompression. Switches should also be made during breathing of the largest inspired oxygen partial pressure that can be safely tolerated with due consideration to oxygen toxicity.

In the case of dry suits filled with light gases while breathing heavier gases, the skin lesions resulting are a surface effect, and the symptomatology is termed “subcutaneous ICD.” Bubbles resulting from heavy-to-light breathing gas switches are called “deep-tissue ICD,” obviously not a surface-skin phenomenon. The bottom line is simple: don’t fill your exposure suits with a lighter gas than you are breathing and avoid heavy-to-light gas switches on a deco line. In both cases, the risk of bubbling increases with exposure time.

More simply, light to heavy gas procedures reduces gas loading, while heavy to light procedures increases gas loading. Note, however, that none of these counter transport issues come into play when diving a closed circuit rebreather.

The NAUITEC Way

ICD is not scientific theory, it is fact. Understanding and avoiding ICD is the way to reduce bubble formation and an increased risk of DCS, and to allow for a more efficient decompression practice in the long term.

Deep trimix dives require a high helium and low nitrogen mix [Note that NAUITEC mandates an equivalent narcotic depth (END) of 30 m, similar to Global Underwater Explorers (GUE)]. NAUITEC takes a hierarchical approach to trimix decompression based on risk reduction.

In its preferred “Zero Order Rule” (zero risk from ICD), NAUITEC recommends that divers not switch from helium to nitrogen (nitrox) breathing mixtures upon ascent. Instead, divers decompress on their bottom gas (trimix) until reaching their 6 m/20 ft stop, and then decompress on pure oxygen (O2). This reduces task loading and minimizes switch changes.

If the diver wants to reduce their deco obligation and/or add a deep deco gas, they would switch to an intermediate deco mix, specifically a “hyperoxic” trimix, also called helitrox or triox, with an oxygen fraction greater than 23.5%. In practice this is accomplished by replacing the helium with oxygen and keeping the fraction of N2 the same, or ideally less. This avoids a N2 slam from ICD. Note that it is recommended that NAUI divers always maintain an equivalent air depth (END) of no more than 30 m/100 f.

This is what we recommend and practice, and we believe it offers less risk than switching from a trimix bottom gas to an enriched air nitrox (EAN) 50, (i.e. 50% O2, 50% N2) at 21 m/70 ft, which is a common community practice. The bottom line here is that in-gassing gradients for nitrogen have been minimized by avoiding isobaric switch. THERE MUST BE A HIGH BENEFIT TO RISK RATIO to deviate from Zero Order Rule!

The additional rules present increased risk. The First Order Rule: No switches from helium to nitrogen breathing mixes deeper than 30 m/100 ft. The Second Order Rule mandates no switches from helium to nitrogen mixes deeper than 21 m/70 ft.

The last rule seems to be common in technical diving, but it has certainly not been formally tested. Just say no when the risks outweigh the benefits. Many times, the benefit of a gas switch does not outweigh the risk. Risk reduction is always the primary goal.

GUE On Isobaric Counterdiffusion

By Richard Lundgren

GUE does not dispute Isobaric Counterdiffusion (ICD) as it’s a natural part of how we achieve decompression efficiency, i.e. maximizing the gradient between the different inert gases in a diver’s tissues and what is being respired. This is sometimes referred to as the positive ICD effect.

The flip side of the coin, the negative ICD effect, involves a potential increased risk for decompression illness (DCI), most commonly subclinical manifestations affecting the inner ear and causing inner ear decompression sickness (IEDCS).

Although the exact mechanics are not known, one potential aggravating factor could well be ICD when the gradient resulting from a switch from a helium to a nitrox mix is too large. This is sometimes called a “nitrogen slam.” This occurs when a gas with slow diffusivity is transported into a tissue more rapidly than a higher-diffusing gas is transported out, like when switching from bottom gas, for example a Trimix 15/55 (15% O2, 55% helium, balance N2) to a nitrox decompression gas like Nitrox 50 (50% O2, 50% N2) at 21m/70 ft. This can result in supersaturating of some tissues and consequently, bubble formation.

Based on ICD theory alone, one could draw the conclusion that any gas switch not containing helium after a trimix/heliox dive would be provocative and increase the decompression stress. This is where academics need to be tuned to the application and empirical evidence.

The practice of “getting off the mix early and deep,” which led some divers to switch to air at great depth in order to maximize the off gassing of helium, was a common early practice in the tech community. It was a practice that most likely resulted in elevated risk of not only DCI, but also inert gas narcosis and the problems it can engender. This practice, as most people likely know, was not subscribed to by GUE.

On the contrary, GUE was the first organization to call for helium-enriched gases when diving deeper than 30 m/100 ft, both for bottom gas and decompression gas. We were also early advocates for switching from helium-based bottom gas to nitrox 50 under special circumstances.

However, it should be made very clear though, that among the very active GUE dive community, we have seen no indications or significant statistics implying that the DCI risk or occurrence is elevated when switching to Nitrox 50 as the first deco gas after a 72m/250ft dive breathing Trimix 15/55. For deeper dives, additional deco gases are used. All of these contain helium.

Another possible issue could occur when divers switch to their helium-based back gas briefly after decompressing on Nitrox 50 but before switching to pure oxygen, and/or taking an oxygen break during their 6 m/20 ft O2 decompression. However, based on thousands of decompression dives in the GUE community, these gas breaks have not been reported to cause problems. Note that these switches occur at shallow depths, and therefore reduced pressure gradients.

Superficial ICD, i.e. when the body is surrounded by a less dense gas compared to what’s being respired is more of a theoretical problem for divers, as we don’t use helium mixes to inflate our dry suits for the obvious reasons of thermal conductivity.

Interestingly, the concerns over ICD may at first glance seem irrelevant to rebreather (CCR) divers, assuming that their diluent remains the same throughout the dive. But remember most CCR divers rely on open circuit bailout, which may require gas switches.

Dive Deeper:

Counterculture and Counterdiffusion: Isobaric Counterdiffusion in the Real World

Note: The British Sub Aqua Club (BSAC) recommends that divers allow for a maximum of 0.5 bar difference in PN2 at the point of the gas switch. According to former BSAC Tech lead Mike Rowley, “The recommendation isn’t an absolute, but a flexible advisory value so a 0.7 bar differential isn’t going to bring the Sword of Damocles down on you.”

Not A Theory — A Fact! References:

NAUI Technical Diver, National Association of Underwater Instructors, 2000.

Wienke B.R. & O’Leary T.R. Isobaric Counterdiffusion, Fact And Fiction. Advanced Diver Magazine

Technical Diving in Depth, B.R. Wienke

Lambertsen C. J., Bornmann R. C., Kent M. B. (eds). Isobaric Inert Gas Counterdiffusion. 22nd Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop. UHMS Publication Number 54WS(IC)1-11-82. Bethesda: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society; 1979; 182 pages.

Doolette, David J., Mitchell, Simon J. (June 2003). “Biophysical basis for inner ear decompression sickness.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 94(6): 2145–50.

Daniel Millikovsky is a lifetime NAUI member (NAUI# 30750). He’s been a NAUI instructor exclusively for 22 years, a Course Director for 20 years, and in 2016, became a Course Director Trainer and Representative in Argentina. Daniel is a very active NAUI Technical Instructor Examiner (#30750L) for several courses including OC and CCR mixed gas diving. He has also been a member of the NAUI Training Committee since 2020. He owns Argentina Diving, a NAUI Premier, Pro Development, and Technical Training Center based in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Daniel began diving in 1993 as a CMAS diver and then continued with his NAUI career, becoming an instructor in 1998. He opened his first NAUI Pro Scuba Center (DIVECOR) in Cordoba, Argentina. Daniel is enthusiastic about teaching and training and is a sought after presenter at numerous international dive conferences and shows. He can be reached at [email protected], website: www.argentinadiving.com.

Richard Lundgren is the founder of Scandinavia’s Baltic Sea Divers and Ocean Discovery diving groups, and is a GUE Instructor Trainer, an Instructor Examiner, and a member of its Board of Directors. He has participated in numerous underwater expeditions worldwide and is one of Europe’s most experienced trimix divers. With more than 4000 dives to his credit, Richard Lundgren was a member of the GUE expeditions to dive the Britannic (sister ship of the ill-fated Titanic) in 1997 and 1999, and has been involved in numerous projects to explore mines and caves in Sweden, Norway, and Finland. In 1997, in arctic conditions, he performed the longest cave dive ever carried out in Scandinavia. Richard’s other exploration work has included the 1999 filming of the famous submarine, M1, for the BBC; the side scan sonar surveys of the Spanish gold galleons off Florida’s Key West in 2000; and the search for the Admiral’s Fleet, an ongoing project that has already led to the discovery of more than 40 virgin wrecks perfectly preserved in the cold waters of the Swedish Baltic Sea.