Community

Getting Back in the Water with Caveman Phil Short

With local diving slowly opening in the wake of the pandemic, InDepth caught up with British cave explorer and educator Phil Short to see how he navigated his post lockdown re-submergence. And what about those 14, 15, 16 month old oxygen sensors?

by Michael Menduno

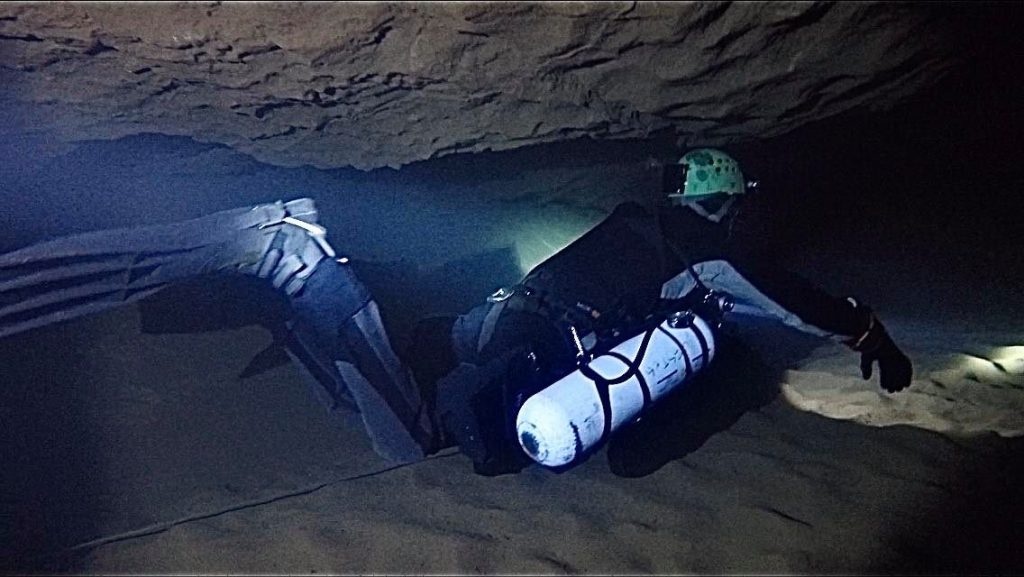

Header photo by Michael Thomas. Phil Short swims under Wookey Chamber 14.

With diving just beginning to resume in various parts of the world after what felt like an interminable shutdown, we thought it would be interesting to check in with some of our friends to see how they were approaching their return to the underwater world after such a long hiatus.

Ironically, it’s been the longest that 51-year old British cave explorer, scientific diving officer, exosuit pilot, educator and film consultant Phil Short, principal of Dark Water Explorations Ltd. has been out of the water in his entire 30-year diving career. How did one of tech diving’s indefatigable pioneers plot his re-submergence, and what would he offer up to colleagues about to take the plunge?

We chatted up Short just as he was booking his first dive project trip abroad; this is what the ardent caveman said.

InDepth: Maybe we can start with you explaining a little about the circumstances in the UK. I know you were on lock down as far as diving was concerned, and they are now in the process of opening up.

Phil Short: Basically, when the COVID-19 crisis began, the country went into lockdown for all nonessential activities. So obviously, any type of sport and recreation was included in that. And then, after about two months, they slowly started to reduce the restrictions, certainly for more normal activities and allowed certain sports to take place again. There was a lot of controversy over diving, because COVID-19 is a respiratory or lung-borne disease. So there was concern that it could create additional potential hazards with lung expansion injuries and embolisms.

In the UK, we have a group called the British Diving Safety Group, which is made up of various organizations including diving training agencies: the British equivalent of the Coast Guard, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), which is our version of OSHA and the diving industry trade organization, and SITA (Scuba Industries Trade Association). I am a member, and we met to determine what the safest and most prudent, most expedited means were to get people back in the water. We consulted with the hyperbaric medical community, COVID-19 related medical experts, the agencies with the authorities that control charter boat operations, and with the HSE.

The first permissions were for small groups. Basically, you and one buddy could do shore dives. We adopted recommendations by the NSS-CDS as to how gas sharing should take place, and safety or S-drills so you are not breathing from each other’s equipment.

So when did you go diving?

As a member of the BDSG committee, I was very diligent not to go in the water until the evening we announced that it was permissible to go beach or shore diving. The next morning, 28May 2020, I left my house at 4 AM to go and do a beach dive on a landing craft from the second world war, a genuine World War II wreck. I descended at 6:23 AM and it was just heaven because I had been out of the water for 86 days because of the restrictions. And it was just great to get back in.

Where did you make your last pre-COVID-19 dive?

My previous dive had been on the island of Lanzarote in the Canary Islands off of West Africa teaching a trimix rebreather class. It was a 93m/303 ft dive. I got on the plane, flew home, and the lockdown started almost immediately. And then 86 days later, I was doing a 12m/39 ft dive off the beach in the UK. It was my longest break in diving in the 30 years I’ve been in the industry.

Let me ask you, did you have a conscious strategy or approach to getting back in the water? You didn’t start back in at 90 meters.

Yes, it was conscious. Certainly rebreathers, it’s not just like riding a bike. You do need to keep current. I recommend to my students to be doing at least one skill dive on the rebreather per month, minimum, to maintain currency.

So I decided that for the first dive, once the permissions had been given, to go make the beach dive on doubles. I’ve got a nice little twin 8.5L set that’s small enough for walking over the beach. It still had the redundancy, but it was simple scuba and a simple depth of just 12m/39ft. Basically, the first thing I did when I got in the water was descend just a few feet and made sure that I was proficient with doing a shutdown and isolation drill on the doubles.

Then I went for the dive on a good nitrox with a long no-decompression time and surfaced way before I was getting anywhere near decompression. I took it gently. First time back in 86 days, I took it gently, and then over the last six or seven weeks, I’ve started to build up from there.

I know you’ve talked and probably compared notes with colleagues and other divers. Do you think people there are approaching getting back in the water sanely or is it a bit of a madhouse? How would you characterize things in the UK?

I would say, as often happens, it’s mixed. So, based on recommendations of the agencies and their instructors, the majority of people are getting back into it gradually like I did myself. But there’ll always be those who say, “Oh, I’m a good diver. I don’t need to do that. I’ve not been allowed to dive for two or three months. I want to go do what I want to do.” And they go straight out and do a 50 or 60m dive, which I think is just foolish.

Even ignoring the COVID-19 situation, if you were out of diving because of having a kid, or experiencing a job change or anything like that, or after a big layoff, I think it would be prudent to get back in gently and then slowly build up. So, my first dive was shallow with open circuit doubles. My next dive was a very limited penetration, shallow cave dive on open circuit, side mount, again with redundancy. A no-decompression dive but back in my natural environment of caves for a little swim around.

Gradually over the weeks, because I had better access to caves than I did to the sea, I did more and more cave dives and slowly built up in duration and distance, but still on open circuit. I then got permission from the owner to access one of the inland lakes, and we did some pre-official opening work for the owners of the site. I got back in on the rebreather but again, no-decompression, relatively shallow, no more than 30m/100 ft. Next, I integrated stages and my DPV (diver propulsion vehicle).

My first teaching was a Level one, Mod One rebreather course that I team-taught with a fellow UK instructor. It was a perfect way to get back in gently because we were running 10 hours over 8 to 10 dives of constant skills for the students. So that was a real refresher. And then finally last weekend, a group of us that had all been doing that type of gradual build up got out on a boat off the south coast of the UK, on a 33 m/108 ft deep wreck on Saturday. On Sunday, we dived a very well-known wreck, the SS Salsette, in 45 m/147 ft of water in beautiful conditions. Calm sea, good visibility, and a real wreck. So I had made a gradual buildup over seven or eight weeks to get to that point, rather than jumping straight back in.

Sweet. You mentioned rebreathers (CCR). Currently, there is a global shortage of oxygen sensors underway as a result of the pandemic. Oxygen sensors are being diverted to the medical industry, which is under siege right now from COVID-19. Any concerns or worries that people will go diving with out-of-date cells? Do you think that’s an issue?

It definitely concerns me. I’ve been a CCR instructor at all the levels, almost exclusively for the last 15 years, and I’ve seen people go out and happily spend five, six, seven, 10,000 pounds on a brand new rebreather and the training and then go out and be cheap on a £16 fill of Sofnolime or a £16 fill of oxygen. And you’re like, what are you doing? You paid £10,000 for this equipment and you’re risking your life on a £16 refill of consumables? People are so desperate right now to get back to their hobby; they feel like it’s been taken away from them, that I worry they may not always act sensibly.

It’s been a battle over the last five or six years to get people to really wake up and pay attention to the fact that these sensors are your life support. There was a very high-profile accident that was caused by overrun sensors a few years back with a quite-well-known person in the industry. He effectively died on the bottom, was rescued by his buddy, then was helicoptered to the hospital where he was put into an induced coma. He came out of it several days later and he was very, very lucky to survive. And very, very lucky to come back to actual diving again. But that was all caused by old, overbaked sensors.

So what do you see happening?

I think what’s going to happen, you know, is that some people ran out of fresh sensors a couple of months ago so now it’s 14 months, 15 months, 16 months. And some may be thinking, “It’ll be okay, it’ll be okay. They’re reading fine, they’re working fine.” Some people might be doing linearity checks, doing oxygen flushes at 6 m/20 ft to check if they read high when appropriate.

But really, the companies like AP Diving, JJ-CCR, Vobster Marine Systems, and others have put a lot of time, a lot of effort, and a lot of money into researching and independently testing these life-support machines for functionality, with certain parameters. Much like car manufacturers do so you can drive your family and your kids in a safe car. [Hammerhead CCR developer] Kevin Jurgenson summed it up once brilliantly when he put out a statement saying, ”Okay, people are questioning the duration that a sensor can last. Some people would say 12 months. Others would say 52 weeks. Some would say 365 days.” And he carried on to include hours, minutes etc. Basically saying, a year is a year. Whichever way you try to stretch it, it’s a year. No more.

Personally, I would not violate that because those three simple galvanic fuel cells that represent probably somewhere between $200 and $300 depending on the manufacturer and the unit, representing a tiny percentage of the expense that I’ve outlaid to become a rebreather diver, is not worth my life.

As I mentioned, I am now back on my rebreather after starting on open circuit, and if my sensors eventually pass their 12-month date, I’m very happy to return to open circuit for as long as I have to while I wait to buy some new cells.

I have always believed in my educational career of thirty years in the diving industry to lead by example. Those are my feelings. I know from experience when you make comments like that, and it’s effectively the same as raising your head above the trench in a warfare situation. People are going to take shots; but bring it on. If you’ve got a sensible, scientific argument for extending your cells past 12 months, then I’m happy to discuss it. But I don’t think there is one.

So the moral is, if you have sensors that are past either one year, 12 months, 365 days, 8760 hours, 525,000 minutes, or 31.5 million seconds, then you need to go back to open circuit, or not dive until you can get some new ones?

I believe so. The manufacturers whose rebreathers I have dived and taught on over the last 10 years are people that were passionate about rebreather safety. And much like [Sheck] Exley, who focused on improving cave training and cave safety by writing Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival, these manufacturers—people like Martin Parker at AP Diving and Jan Petersen at JJ CCR have gone the extra mile to improve safety.

You know full well from the aquaCORPS days, if you look at the safety record of CCR diving now, versus 15 years ago, we made a difference. It has become safer. Why ruin it, because of impatience and a short-term, relatively short-term, restriction on availability of consumables?

Right. In fact, I have talked to Nicky Finn at AP and also Jakub Sláma at Divesoft who have been in touch with sensor manufacturers regarding shortages, and it seems that the situation may be stabilizing and or easing up, assuming we don’t have a second wave of COVID-19 infections. So hopefully, the situation will improve.

Actually, I’ve heard that from several manufacturers, and I think it will improve quicker than was first anticipated. And that’s even more of a reason for not doing anything foolish and being a little bit patient with this to be safe.

Last question: What’s next for you? Got any big projects coming up?

I just booked my first flight to travel out of the UK again. This time to Croatia. I’m going to be designing and building a water dredge system for recovering and capturing sediment on an archaeological site for a project that we are going to do in October. This is a follow-up project from one we did in 2017 to recover a US World War II pilot from a wrecked B24 bomber that ditched in the Adriatic Sea. We’re going back to do another recovery on a different wreck.

The dredge system will be designed to work at the appropriate depth level so that we can basically recover the sediment without losing anything. Specifically, we’re not going to miss any of the crew that are found through that dredging. So, I’ve got a 10-day trip to build that system, test it in the same depth of water, and have it ready for the project.

When I come back from that, I’m flying out to Switzerland to train on the Divesoft Liberty sidemount with a good friend and former student of mine, Nadir Quarta. It will be my first sidemount rebreather. I’ve got no intention of moving away from my JJ as my primary rebreather, but I’ve got quite a few cave projects that require a side mount that I can’t do in my back-mount JJ. They don’t offer a sidemount, and because of distance and depth, I can’t do it on open circuit. I put a lot of thought into which unit to use, and am very impressed with Divesoft’s engineering and build. They’re also very courteous and professional to deal with. I like working with people like that.

After training, I plan to attend a Swiss technical dive conference, Dive TEC! in Morges as a speaker, where I will be talking on my 30-year journey as a cave diver and explorer.

Fun times ahead! Thank you, Phil. I look forward to talking to you again soon.

Thank you!

Michael Menduno is InDepth’s executive editor and, an award-winning reporter and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.” His magazine “aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving”(1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving. He also produced the first Tek, EUROTek, and ASIATek conferences, and organized Rebreather Forums 1.0 and 2.0. Michael received the OZTEKMedia Excellence Award in 2011, the EUROTek Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012 and the TEKDive USA Media Award in 2018.