Latest Features

Exploring Virgin St. Lawrence Wrecks

Shipwreck explorers Sébastien Pelletier, who also serves as editor-in-chief of En Profondeur, joins up with Kevin Brown to report on their 2021 expedition to the St. Lawrence Estuary, where they discovered two virgin wrecks; the barge Donnacona no. 1 that sank in 1942, and what they believe to be is the Otter, a two-masted schooner, which sank in 1898. In the process, they struggled with challenging conditions and Brown was nearly lost at sea. Exploration ain’t for the faint of heart.

By Sébastien Pelletier and Kevin Brown. Photos courtesy of Quebec Technical Wreck Divers (PETQ) and Outaouais Technical Divers (PTO Exploration). Multibeam images courtesy of Richard Sanfaçon.

Diving to discover never-before-visited wrecks in the inhospitable waters of the St. Lawrence River Estuary, Canada, one of the deepest and largest estuaries in the world, where conditions can change quickly and without notice, requires thinking outside the box. To do this, it is often necessary to invent a recipe, an element which carries its share of risks.

The St. Lawrence River contains a multitude of wrecks. Some are disturbing, like the remains of the cargo ship Corfu Island, which sometimes leak odors of heavy fuel oil through the sand of the Magdalen Islands. Others, like the Empress of Ireland liner, make you nostalgic. However, the vast majority remain invisible to everyone.

Every year, the Plongeurs d’épaves techniques du Québec/Quebec Technical Wreck Divers (PETQ) and Outaouais Technical Divers (PTO Exploration) clubs organize a joint expedition on (preferably unexplored) wrecks in Quebec. In 2021, they managed to reach two of those: the coaster Donnacona no. 1 (from the marina of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli (SJPJ) in the Chaudière-Appalaches region) and a schooner not yet identified (approximately 100 km/62 mi downstream off the coast of Cacouna in the Bas-Saint-Laurent (see map)).

Looking For Favorable Weather

In order to maximize the chances of success, the team opted for an attempt during the month of July. The objective was to take advantage of both the increase in water temperature and the reduced risk of strong wind and fog, always including the window of adequate tides in the equation; we wanted the tides to be as low as possible, but these last just a few days per month.

With an expected duration of 10 days, the expedition did not begin as planned. When we arrived at Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, we noticed that things didn’t look good. A strong wind from the northeast had already been blowing for several days. Coming from downstream of the St. Lawrence to upstream, this wind—called Nordet—generally brings cold temperatures and blows directly against the current, often leading to the creation of sneaky waves.

Therefore, the first two days of diving were canceled. Only available at the start of the expedition, two of the team members, Sylvain and Claude, returned home, taking their boat with them. This second boat would have provided additional security since it was to be used specifically to recover divers who were likely to drift away.

Race Against Time

On the third day, the winds seemed to decrease just below the acceptable threshold which allowed an outing on the river. However, this presented a tight time window; since the marina did not have enough water at low tide, we waited until mid-tide to put the zodiac in the water, then returned before the water level dropped too much. A real race against time began, with the divers only having a few hours to complete their excursion. At the slightest delay, the group would be stuck and would risk running out of fuel or face changing weather conditions. In addition, the strong winds created even bigger waves than expected, forcing a slowdown in cruising speed.

A Demanding Dive

As soon as they could, the divers left the marina and headed toward the wreck. Once they arrived at the site, security maneuvers began. After a long and difficult grappling operation—an essential step, especially in the waters of the St. Lawrence River, aimed at ensuring a safe descent along a cable with a grappling hook at its end—it was time to put both first divers in the water, Steve and Sébastien.

Their job was to secure the mooring on the wreck and bring the grappling hook to the surface using a lift bag. This would then be the signal for the third diver, Kevin, to join in. Due to poor conditions, he decided to leave his heavy camera on the surface. In addition, the water being brownish, with at best 0.5 m/2 ft of visibility, taking beautiful images was a difficult task.

Upon reaching the wreck 17 m/56 ft below, Kevin noticed that his dry suit was taking on water. Not knowing precisely where the leak came from—perhaps a cut due to the sharp and rusty edge of the wreck’s gunwale—and, given the expected short bottom time (20 minutes), he decided to continue exploration anyway. This was a mistake. But Kevin didn’t know that yet.

Notwithstanding the very limited visibility, the ensuing exploration validated the nature and identity of the wreck. We were able to confirm that this was indeed a steel-hulled vessel. This observation was made in addition to the fact that the shape and dimensions of the wreck—the latter extrapolated from the multibeam echosounder images taken during the discovery of the wreck in 2007 by the Canadian Hydrographic Service—corresponded to those of the potential candidate. No more doubts, the motor barge Donnacona no. 1—built in 1928 and sunk in the fall of 1942 due to bad weather with her six crew members—had received its first visitors.

Return to the surface

Anticipating a laborious return to the surface because of the waves, the first two divers decided to end their visit prematurely. To prevent the captain from having to simultaneously manage the ascent of several divers—a crane on the zodiac was used to winch the heavy equipment on board the boat—the divers always made sure to let a few minutes elapse between each exit from the water. This instruction was of great importance, especially when encountering bad weather.

Therefore, Sébastien was the first to come out of the water, but not without the difficulty of a laborious climb. He noticed that the weather was magnificent, but that the waves had practically doubled in size. “We dive into the river when we can, not when we want,” the old adage goes. She opened her arms to us for a few dozen minutes, but then they were closing and we began to feel her embrace… We had to leave this place!

Eight minutes later, Kevin began his ascent. Once on the surface, he realized that it was impossible for him to hold on to the cable because the current had started to accelerate very quickly. Risking shortness of breath—something to be avoided, especially when diving in a closed circuit—he considered it safer to let go and let himself be carried away. Sébastien shouted at him to inflate his gear and let go. He also warned Kevin that Steve would be picked up first since he’d experienced the same scenario: he, too, had drifted and was now heading toward the shipping channel.

Lost at Sea

As he moved away from the boat, the size of which he saw gradually diminishing on the horizon, Kevin understood that soon it would no longer be visible. He then deployed his surface marker, a cylindrical buoy almost 1.5 m/5 ft high.

After a long fifteen minutes, the boat finally reappeared in the distance. Kevin thought that Steve must have been back on board by then. Between the waves, he saw the boat coming back, but not quite toward him without slowing down or stopping. It was only after the zodiac completely disappeared from his field of vision that he realized the magnitude of the situation: he was lost at sea.

Kevin waited another fifteen minutes. By then, he could no longer see the shore. The waves were behaving like an almost permanent wall, making the surface marker invisible to the occupants of the boat. To make the situation worse, his dry suit, which had started to take on water during the dive, was now partially flooded.

Alone, surrounded by water, and drifting toward the navigation channel, Kevin brought out the heavy artillery and decided to activate his emergency radio beacon to signal his position to all the vessels in the surrounding area.

Additionally, he launched a flare that rose nearly 30 m/100 ft above his head, illuminating the sky for a very brief moment. Time seems to slow down when we feel helpless, waiting for rescue, and Kevin wondered how long he could last with a suit flooded with cold water if the beacon didn’t work.

The Rescue

Finally, after another quarter hour, the boat reappeared between two waves. The other Sébastien, our captain, then took the radio and immediately contacted the authorities to inform them of the outcome of the situation and, who knows, to cancel the rescue helicopter which was perhaps preparing to take off. The emergency signal finally reached the Coast Guard.

We came to two conclusions: a green surface marker, whose color was similar to the water, was not optimal. The safety orange color is the most appropriate in these conditions. As for the flare, it was never seen. Kevin was at a great distance, and this type of device is naturally much more effective at night than in broad daylight.

The Need For Security Gadgets

Some might think we were going a bit overboard with all these security gadgets. But facing the unknown in hostile waters with powerful tidal currents outside of one’s comfort zone means that things can sometimes not go to plan. How would the day have ended without the emergency beacon? We don’t know. However, one thing is certain: Kevin proved to be stronger than our grappling hook, which was bent by the force of nature that day.

It had been a long time since such a shallow wreck had given so much trouble. We understand better why this wreck, to our knowledge, had never been visited before. Needless to say, the beer tasted good that night!

A Wreck to Identify

This mishap did not dissuade us from undertaking the second phase of the expedition: exploring our second target near Cacouna whose presence was detected by the Canadian Hydrographic Service in 2009 and declared to the competent authorities. Once again, due to bad weather, we unfortunately lost another day.

Once more, we planned dives at high tide because it brought clearer (though colder) ocean waters. Even though it was less than 100 km from Donnacona no. 1, water conditions were completely different. The grappling operation went smoothly, especially since we were protected from the wind by an island.

Splashing In

This time, Kevin was the first to get into the water. Sébastien followed shortly after to help secure the mooring. They were both happy to see the presence of a manageable current. Once they reached the wreck at a depth of 28 m/92 ft, they noticed that its hull was made of wood. This was a significant observation because it meant that the wreck was older than we initially thought. Incredible visibility greeted them and allowed them to see nearly 10 m/33 ft in each direction—extremely rare conditions in this sector.

Unlike the total darkness we expected, the water was instead dark green in color and remarkably clear with few suspended particles. As they swam along the hull toward what appeared to be the stern, the divers glimpsed an opening in the hull. A second glance allowed them to see the inside of a cargo area. As this one was filled with barrels, it must therefore have been a merchant ship.

Suddenly, not far away, Sébastien pointed his headlight at Kevin to let him know that he had just come across something interesting. As Kevin drew closer, he heard Sébastien trying to say something through his regulator. That’s when Sébastien pointed out two jugs about 50 cm/1.6 ft high in remarkable condition! But it was already time to leave the wreck and they ended the dive.

The exploration continued over the next two days and allowed the team to focus more on the deck and the exterior of the wreck, where they observed numerous remains of barrels, some plates, pulleys, bottles, and other artifacts.

Post-dive

Following the expedition, the team reported their observations to the Ministry of Culture and Communications of Quebec and began establishing a time interval of the shipwreck based on the various inscriptions found on the pieces of tableware. The analysis allowed for the deduction that the boat sank after 1894; a plate with a symbol of the devil and a unicorn could have been produced from that year (between 1894 and 1936). Another one must have dated from before 1890 (between 1837 and 1890), and a last one had probably been made between 1830 and 1856.

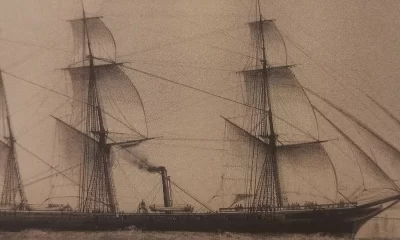

According to the archives consulted, few ships sank near White Island after 1894. The newspaper Le Soleil highlights four of them—the Derwent Holme (1897), the Otter (1898), the Manchester Importer (1902), and the Mignonette (1909). The Derwent Holme was carrying planks and was refloated. The Manchester Importer was not made of wood; she was a modern vessel, and her cargo had been unloaded onto relief barges. As for the Mignonette, she transported wood. Thus, there probably remains only the Otter, piloted by Captain Bernier, which ran aground near White Island in November 1898 during her last voyage of the year from the North Shore to Quebec City. There would have been no deaths, but the loss would have been total.

According to Le Soleil, she transported fish (cod) which, at the time, was stored in barrels. This two-masted schooner, rebuilt twice and converted to steam, was already very old. It is therefore reasonable to believe that the wreck visited is possibly that of the Otter, ex-Margeretha Stevenson, purchased in England by MM Molson and sold in 1878 to Fraser and Co.

The opinion of archaeologists would perhaps allow the team to carry out a formal identification. As a matter of fact, the deductions, established from photos and an encyclopedia on pottery, are not comparable to archaeological work. To be continued.

In order to explore this completely unique underwater environment, conducting dives in the St. Lawrence estuary requires a keen sense of adaptation. To be the first to reach a virgin wreck, one needs experience, daring, and perseverance, but also humility and wisdom.

However, during an expedition, divers tend to push their limits, sometimes perhaps a little further than they should, thus reducing the room for maneuvers available to us. The consequences of a bad decision or poor risk management can then be serious. Sudden fog, increased wind, or an unexpected change in tide can significantly change plans. There are multiple reasons why so many of these wrecks remain pristine.

Expedition members :

Sébastien Pelletier, diver

Kevin Brown, diver

Steve Doyon, diver

Sébastien Savignac, captain

Jean-Pierre Richard, captain

Sylvain Brunet, captain, diver, support team

Claude Bureau, diver, support team

Thanks to Richard Sanfaçon, Alain Franck and Hubert Desgagnés for their valuable help.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: La Grande Dérive By Marc-André Dubois and Pierre-Olivier Dubois.

InDEPTH: The Devil In Your Dive: My 70-km Traverse of the St. Lawrence River by Nathalie Lasselin

InDEPTH: Faces of Diving by Benoit Bruhmuller and Andreanne Lapointe-Aubert.

Sébastien Pelletier is the editor-in-chief of En Profondeur, the only French-speaking magazine in North America dedicated to underwater activities, a Ph. D. candidate in geographical sciences at Laval University and the leader of PETQ (Plongeurs d’épaves techniques du Québec / Quebec Technical Wreck Divers), a dive team specialised in visiting unexplored sites and the first to reach two of the three largest shipwrecks in Quebec (SS Leecliffe Hall and MV Tritonica), often collaborating with maritime museums of the province. Accumulating more than 30 years of diving experience, his curiosity for the underwater environment led him to explore various oceans, seas and lakes of the world in addition to spending a few years in the oil and gas offshore commercial diving industry in the Gulf of Mexico and in West Africa. He now devotes most of his underwater activities to exploring the St. Lawrence River, in search of adventure and discovery. Father of two children, he lives in Montreal.

Kevin Brown is an anthropologist (M. A.) specializing in maritime culture, shipwrecks, and deep diving. He is the founder and leader of PTO Exploration, a Canadian deep diving team currently collaborating with University of Ottawa (Anthropology Department) and University of Quebec in Montreal (Microbiology Department) for a multi-disciplinary study on abandoned flooded mines. During the past seasons, this project discovered new life forms. With over twenty years of diving experience, Kevin teaches Trimix Rebreather diving in several environments from cold water to overhead, helping shape the next generation of technical divers. He participated in the discovery and exploration of multiple shipwrecks that resulted in an assignment of Borden codes. Kevin contributes frequently to Canadian scuba diving magazines such as En Profondeur and, in the past, DIVER. His videos also have been viewed in museums and several programs.