Conservation

Are You A Culturally Responsible Wrecker?

Founder and president of Ocean Education Int’l, Dr. Alex Brylske explains his evolution from “reaper”—have chisel and hack saw, will pillage— to an environmentally-aware wreck diver who cares about and acts to preserve our submerged cultural heritage. Here the good doctor explains why protecting our submerged heritage is, and should be, important to all of us. Remember, the culture you save may be your own! (2024)

By Alex Brylske, PhD. Lead image: Karl Shreeves on the wreck of the USS Monitor. Photos by Roderick M. Farb used by permission of the NOAA Monitor Collection.

The Case for Preserving Our Submerged Heritage

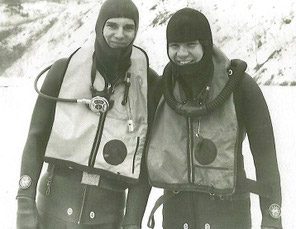

Growing up in Maryland, my coming of age as a scuba enthusiast in the 1970s meant becoming a wreck diver. What began as a teenage pastime of exploring the plethora of shipwrecks off the New Jersey and Delaware coasts soon blossomed into an obsession that determined the direction of my life and career. At the time, the typical wreck diver ensemble included twin 71.2 (11L) “steels” linked with a crossover bar, a “quarter inch” Farmer John wetsuit, and a leg-mounted knife any Roman gladiator would have been proud to carry into the arena. By that time, single-hose regulators were the norm, but only sissies were equipped with an “octopus.”

For those with sufficient means, you might have seen a Fenzy ABLJ (Adjustable Buoyancy Life Jacket) and an analog “Bend-O-Matic” decompression meter. However, as a destitute student, I had to settle for a UDT-style “life preserver,” a capillary depth gauge, and a copy of the trusty old US Navy Standard Air Decompression Tables.

While this was the kit of virtually every cold-water diver of the time, we wreck divers often carried additional tools, such as a chisel and three-pound maul. (I even remember a few die-hards armed with pneumatic tools powered by their low-pressure inflators.) The reason for the extra hardware, aside from letting you take considerable weight off your belt, was the objective of our dive—we were “hunting for artifacts.”

In other words, we were there to pillage the wrecks for anything of interest, even if it meant ripping it from the security of its hull or superstructure. I shudder to think of how much time I’ll spend in purgatory for these deeds. Clearly, today’s world is a different and more enlightened place…for the most part.

As a reformed wreck reaper, I’ve vowed to reduce my time in purgatory by helping divers see the error of my ways. My conversion began when I had the opportunity to spend quite a bit of time with some outstanding maritime archaeologists who showed me that every ship that’s ever ended her career on the sea bottom has a story to tell. And these stories are not only interesting: they are important and often overlooked historical events. Far from rusting pieces of metal or rotting wood, they are cultural relics that are part of our common human heritage and deserving of respect and preservation as much as the Pyramids of Giza, the Great Wall of China, Stonehenge, or the Anasazi cliff dwellings of the American southwest.

Windows Into the Past

Few would disagree that a responsible diver should show deference to the environment, which is, after all, where we dive. Yet, we often fail to realize that the “environment” has both biological and cultural elements. So, just as we should respect the ocean’s living resources, so too should we respect submerged cultural resources.

And, by the way, a submerged cultural resource isn’t just a fancy way of saying shipwreck. It’s an inclusive term describing any historically significant remains located underwater. Aside from shipwrecks, that can include anything fully or partially submerged, such as the remains of docks and wharves, navigation aids, lighthouses, as well as ancient settlements of Indigenous peoples or entire submerged towns, such as the 17th-century pirate haven of Port Royal, Jamaica.

Artifacts—defined as any objects manufactured or modified by humans—exist in all forms and come from all ages past. They reflect every aspect of human culture. They explain how people lived, engaged in commerce, fought wars, exchanged ideas, and developed technology. Artifacts can range from the charismatic—like ships and armaments—to the mundane, such as pottery, glass, brick, wood, leather, fabrics, and common tools. Yet, no matter their size or relative importance, every object has a story and deserves preservation so that story can be told.

Another emerging issue in maritime archaeology is that not all submerged cultural resources were originally lost at sea, and not all submerged cultural resources involve ships or even nautical history. Human migrations have occurred for tens of thousands of years, but it’s believed people reached North America only over the past 20,000 to 25,000 years. The ability to use watercraft and easy access to food resources often made travel along the shoreline a better choice than an inland journey. But shorelines change.

With the warming of the earth—and subsequent melting of the massive ice cap covering a large portion of the northern hemisphere beginning about 18,000 years ago—sea levels have risen more than 120 meters/400 feet. Since then, many early coastal migration routes are now underwater, along with the settlements and artifacts that went with them. Some anthropologists believe that we may never fully understand how humans populated the world until we can find and excavate long-inundated coastal sites that have been underwater for thousands of years. Since the invention of scuba, many of these submerged sites are now accessible. But their ease of access also means uncaring or clueless recreational divers may beat archaeologists to the sites, destroying much of their rich archaeological value.

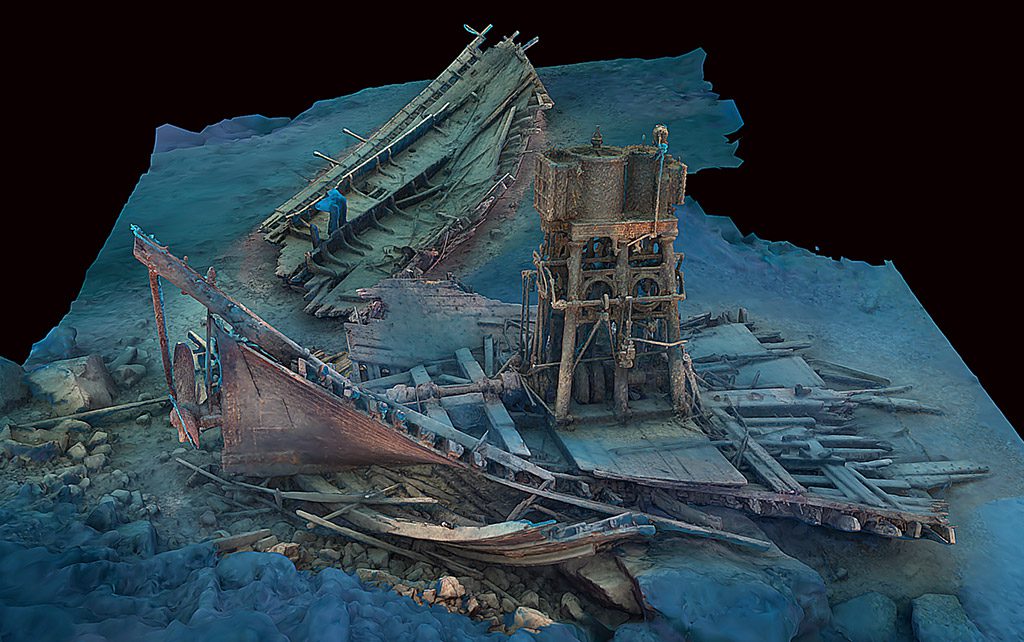

Still, another important and recent factor in protecting cultural resource sites is that depth no longer safeguards as many shipwrecks as it once did. The capability of technical diving is continually pushing the depth to which divers can explore. Shipwrecks and other cultural resources are now accessible at depths barely imagined only a few decades ago. For example, the iconic ironclad USS Monitor wreck site, once considered inaccessible due to its 71 meters/235 feet depth, is now well within that range of today’s technical divers.

Roderick M. Farb used by permission of the NOAA Monitor Collection.

A rich treasure trove documenting the human experience rests on the bottom of the oceans, lakes, and other bodies of water, and these objects can yield a wealth of information about human history and civilization. But there’s one important caveat if society is to gain the most from these invaluable cultural resources: they must remain in place and be left undisturbed.

To understand why, it’s useful to use this analogy: artifacts are to archaeology what cells are to biology. They tell a story; however, it’s one that’s understood only in a collective and organized context. But there’s an important difference between archaeology and biology. Biologists study living organisms that grow and reproduce—they regenerate—unlike alogists, who only get one shot. As any archaeologist will attest, while artifacts are important, the real story is in their setting, and once the context of a site is disturbed, there’s no going back. (This is why meticulous documentation is a vital component of archaeology.) Unfortunately, many historical shipwrecks and cultural resources have already been scavenged by divers in search of trophies and souvenirs, thus depriving posterity of what might have been learned and shared for the common good.

The importance of context in understanding artifacts is one reason shipwrecks are especially valuable to understanding our past. Consider, for example, that during the Age of Sail when a ship put to sea, it could be gone for months or even years, and it could in no way depend upon support from “home” or even another ship. The significance of this complete isolation and self-sufficiency cannot be overstated. Compared to most land-based excavation sites, shipwrecks provide archaeologists with a “closed context.” As the land-based sites were often centers of human settlement for centuries or longer, artifacts are normally layered and mixed together, making their interpretation challenging and sometimes uncertain.

But shipwrecks are like a time capsule—a microcosm of culture. They are, in essence, a snapshot of a specific time and event. Therefore, shipwreck sites yield valuable, unique insights—not only about ships—but the evolution of many aspects of technology, medicine, navigation, warfare, commerce, and language. And given that the ocean was, and still remains, the major route for trade, shipwrecks also tell us about how ideas, culture, and even diseases were dispersed around the world.

Some may minimize the importance of archaeology to justify disturbing potential heritage sites, claiming that understanding the past can always be accomplished by historians. But the fallacy in that argument was exposed by Winston Churchill’s famous quote, “History is written by the victors.” Archaeology is a way to “ground-truth” history, to corroborate what historians tell us. Furthermore, archaeology can tell us about the people historians ignore or those without written records. Archaeology helps bring to life a richer history of the common people who deserve their stories told as much as any famous figure historians say is important.

Another new aspect of how shipwrecks are viewed, and in some cases now studied, is their biological importance. Whether historically significant or not, shipwrecks are unplanned artificial reefs and, therefore, habitats for marine life; sometimes they’re even havens rivaling nearby natural reefs. Based on the recognition that shipwrecks are so multi-faceted, some archaeologists now maintain that heritage awareness requires redefining exactly what constitutes an “ecosystem.”

Specifically, they argue the very definition of an ecosystem should go beyond living organisms and include physical structures. As one archaeologist asserts, “Ecosystems have a cultural component, and that means we need to preserve what’s down there, not just for the sake of science, but also to understand our culture and history better. Because of these synergistic relationships, divers must understand why it’s important to protect both the biological and cultural integrity of the places they visit.”

Culturally Responsible Diving

Becoming a culturally responsible diver requires knowing what issues are relevant to preserving our underwater heritage. Like land-based sites, the primary concern for submerged cultural sites is protection from looting and disturbance. However, protecting shipwrecks poses some unique problems. One is, for people other than divers, shipwrecks lying on the seafloor in some distant ocean are clearly “out of sight and out of mind.”

This gives rise to the same problem faced in conserving biological resources like coral reefs: How do we convince people to protect something that they’ll never really experience and therefore feel has no significance to their lives? Aside from the vicarious experience of photos and videos, shipwrecks are accessible only to divers, which makes divers a prime concern—and hopefully ally—in protecting them.

Another major problem in protecting submerged cultural resource sites is that they’re viewed very differently from land-based sites. Today, most responsible people would never consider blithely digging up an unidentified burial ground or rummaging for artifacts as they stroll through a historic battlefield. With shipwrecks, the attitude is very different. This stems from an age-old mentality—legally codified in the maritime law—of “finders-keepers” and is bolstered by the misconception that all shipwrecks contain treasure. Of course, to an archaeologist, all shipwrecks do contain treasure, but not necessarily the silver and gold variety. Their real treasure is in what shipwrecks can teach a society about its past. As one archaeologist has put it, “In archaeology, what’s important isn’t what we find, but what we find out!”

Whether or not underwater cultural resources will be preserved for the future depends on how people who encounter them behave. And problems can arise from either intentional or unintentional behavior. For example, looting and souvenir collecting are clearly intentional. Looting is a commercially-based activity—literally “mining” a cultural site—to sell the artifacts to collectors. And it’s more widespread than most people realize.

By contrast, looting is distinguished from souvenir collecting in that the latter involves taking an artifact as a keepsake as proof of visiting a site. While most responsible divers will decry looting, many still defend souvenir collection as somehow being earned by the experience of being there or will reason that they’re not taking much or anything important. But this is spurious rationalization. As archaeologist Dr. Della Scott-Ireton explains, “When people ask me why it’s wrong to take things from shipwrecks, I ask them a simple question: You’d never even consider visiting Mount Vernon the Tower of London or the Great Wall of China and chipping a brick out of the wall as a keepsake. Of course not. So how is bringing back a piece of a historic shipwreck any different?”

Of course, those who like to rationalize argue over what exactly constitutes a “historical” wreck. Legally, shipwrecks are deemed “historical” once they’ve been sunk for 50 to 100 years. (The specifics are defined legally according to location and jurisdiction.) But historical significance is really a matter of perspective. For example, cheap toys from the 1950s were once discarded as “junk” only to be revitalized in antique shops today as “mid-century collectibles.” This makes a powerful argument that almost any shipwreck on the seabed for more than 50 years is historically significant. To this end, many of the artifacts taken from shipwrecks—now rusting in backyards or adorning the shelves of homes and dive shops—are actually stolen cultural resources denied the chance of adding any insight into the past.

Unintentional damage can be equally problematic. Like diving on a coral reef, poor buoyancy control, dangling gear, or just resting or hanging onto a wreck can be overtly damaging. However, divers can do great harm in subtler ways by compromising the integrity of a site. Even if nothing is taken or destroyed, disrupting the relationship between artifacts by moving or dislodging them can ruin the context of a site, effectively destroying its ability to contribute to the understanding of a society’s cultural heritage. While biological resources can be restored if left alone, cultural resources cannot “grow back,” making them irreplaceable and non-renewable. When shipwrecks or other cultural sites are damaged or destroyed, whatever knowledge they could provide about the past is lost. Like biological extinction, once gone, they’re gone forever.

The “Get it Before it’s Gone” Myth

Exactly how much information cultural resources can provide depends on their degree of preservation. Often, the conditions that cause a shipwreck are quite violent, and the remains are broken and scattered about the sea bottom. The wreck of Nuestra Señora de la Atocha, of Mel Fisher fame, lost in a hurricane, was strewn over a 16 km/10 mile tract. Then, especially when the wreck occurs in the sea, the remains are subjected to one of the harshest environments on earth. So, unlike the Hollywood image of intact ships with flowing sails quietly resting on the sea bottom, shipwrecks often appear to the untrained eye as little more than underwater junk piles, making it easy to rationalize taking souvenirs because “it’s all going to turn to rust or be eaten by worms, anyway.” But that’s not the case. To archaeologists, these “junk piles” can yield as much knowledge as any library, allowing underwater detectives to piece together—like a jigsaw puzzle—life aboard the ship and details of its demise.

Furthermore, while the sea can be quite destructive, it also has an amazing capacity for preservation. Wooden objects, once covered by sediment, can remain intact for centuries. Blackbeard’s famous flagship, Queen Anne’s Revenge, sank in 1718, but when discovered in 1996, the site still contained an extensive inventory of artifacts because it was covered by sand for most of that time.

However, preservation isn’t limited to wood; even ferrous metals can survive in the marine environment. Over time, chemical deposits accumulate in a process called concretion, effectively encasing the metal in a protective coating. Concretions form primarily around iron artifacts. As the iron corrodes, it disturbs the pH of the calcium carbonate and carbon dioxide around it, which bonds with the corrosion products and surrounding soil to form a hard concrete-like layer. Although the iron corrosion isn’t stopped completely, much of the original metal of the artifact may be saved during the conservation process.

Even metal artifacts that have completely corroded away can be re-created in the lab by breaking open the concretion, cleaning out the corroded artifact remains, reassembling the concretion, and filling the cavity with epoxy. Once it hardens, the epoxy replicant is an exact duplicate of the original artifact. In this way, delicate items completely rusted away can be brought back to life for further study and display—but only if they’re left undisturbed before discovery

In any case, the vital condition for abatement in the deterioration of a shipwreck is that it is continually protected by its covering of sand, mud, or sea growth. When wood is exposed, either by shifting sands from storms or intentionally by divers, it’s soon ravaged by marine worms (the often-cited wood-eating teredo worm—Teredo navalis—is actually a mollusk, not an annelid) or other invertebrates and microbes. In the case of ferrous metal artifacts, removal of the protective concretion rapidly accelerates the corrosion process.

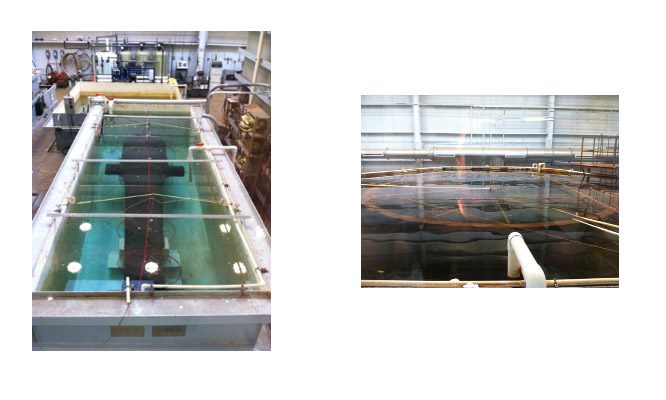

This rapid process of deterioration from oxidation is greatly accelerated when waterlogged objects are removed from the water and not properly conserved. The exact process of conservation varies according to the material in question. Yet, all methods are long and tedious, often taking several years or even decades. For example, submerged wood will lose cellulose in its cell walls over time, and the molecular spaces become filled with water (which helps the cellular structures keep their shape). If the wood is exposed to air, the excess water evaporates, and the resulting surface tension inside the cell walls causes them to collapse with considerable shrinkage and distortion.

Therefore, conserving wooden artifacts involves continually soaking or spraying with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) or similar substance to replace the water within the wood cells. Otherwise, the wood warps, twists, and eventually crumbles away to nothing. This is a time-consuming process, to say the least. One example is Henry VIII’s flagship, Mary Rose, which sank in 1545. The vessel was later recovered from England’s Portsmouth Harbor in 1982. Then, she required continuous spraying of PEG for 30 years before she could be put on display for the public!

In the case of iron objects immersed in the marine environment, over time, they become contaminated with chlorides (salts). If not removed after the iron is taken from the sea, chlorides cause damage through electrochemical corrosion. However, years—even centuries—of concretion can be removed by a process called electrolytic reduction. This involves creating an electrolytic cell with the iron artifact as the cathode. This removes the chlorides and stabilizes the metal. Although it doesn’t necessarily remove the concretion, it can sometimes loosen it by breaking the bond at the interface with the artifact. This, too, is a very lengthy process. For example, in the case of the ironclad USS Monitor, it will take decades to reduce the corrosion and remove all the chlorides from the recovered turret. Once completed, iron artifacts are treated with chemicals to prevent further corrosion. Artifacts of ceramic, glass, bone, leather, and other types of metal also require specific conservation treatments to ensure they will last for years of study, curation, and display.

Sadly, one of the best places to witness the fate of iron artifacts that weren’t properly conserved is the Florida Keys. A once-common sight along Highway 1—the Overseas Highway—were anchors and cannons recovered by early treasure hunters from centuries-old wreck sites before they were protected. Used as ornaments to lure tourists into roadside businesses, these maritime objects were never properly conserved after salvage. Now rare, these irreplaceable relics of Florida’s rich colonial history that survived for centuries in the sea are deteriorating into piles of rust after only a few decades in the open air. Yet, as seen in many museums, if properly conserved they could have lasted indefinitely.

What may be even more surprising to wreck diving enthusiasts—including those who are strong conservation advocates—is that every excavation’s eventual goal is not recovery. Often, the best option is to leave the artifact in place. One reason is the extreme time and expense of conservation if it’s removed. As mentioned previously, this can take decades, and except in the most exceptional cases, the continuing expense of proper conservation often rules out the option of removal. But practical obstacles aren’t the only reason for sometimes leaving a shipwreck where it was found. As the late, former Florida State Underwater Archaeologist Roger Smith explained, “We must assume that we aren’t as smart as future archaeologists.” In other words, the capabilities that might exist in the future aren’t always possible to imagine.

So, by leaving artifacts that have been buried and stabilized on site, not only is there a savings of the huge expense associated with conservation, but their preservation and interpretation will very likely be enhanced by improved future techniques and technology. As Smith asserts, “Long ago, before many techniques of modern archaeology were developed, most of Florida’s Indian burial mounds were excavated by early archaeologists who were more interested in adding to collections than studying human remains and their associated burial goods. Who knows what we could have learned had some of these sites been set aside for the future, to be excavated using modern methods and then hardly-imagined technology like DNA sequencing?” These considerations, combined with the natural preservation afforded by being left underwater, give a powerful rationale to leave artifacts—and even entire shipwrecks—where they are on the sea bottom and protect them for future researchers.

Yet, even when objects are recovered, Smith’s cautionary tale about technology is still valid, and there’s no better example than the Antikythera Mechanism. This nondescript encrusted object was found in 1901 on an ancient Greek shipwreck sometime between the years 70-60 BCE off the island of the same name. Initially, archaeologists were unable to make sense of the artifact, but they soon discovered it was a mechanical device (initially thought to be a clock or navigation device called an astrolabe). However, in the 1970s, using x-ray technology, scholars deduced it was an orrery—a device used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses. It was, in fact, the world’s first analog computer and used, among other things, to track the four-year cycle (Olympiad) of athletic games (which were the origin of today’s Olympic Games).

Then, in 2006, computerized tomography (CT) scans revealed even more details of the inner workings and hidden inscriptions. So, it took more than 100 years and major technological advancements for the full story of one of the most important mechanical devices in Western history to be told. Who knows what technology might make possible in the future?

Perhaps someday, entire historic shipwreck sites will be displayed in full detail by virtual reality 3-D imaging while leaving them undisturbed on the bottom. While that may not sound too enticing for a seasoned wreck diver, it may well be appreciated by future generations.

NOTE: The author would like to thank Dr. Della Scott-Ireton, Associate Director of the Florida Public Archaeology Network, and Dr. Cory Malcolm, archaeologist and Lead Historian at Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, for their assistance in this article.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Take Only Pictures, Leave At Most Bubbles? The Case for Wreck Preservation by Rupert Simon

InDEPTH: Protecting Stellwagen Bank Sanctuary’s Shipwrecks: An Opportunity for Collaboration By Ariel Silverman

InDEPTH: Confessions of an Aspiring Shipwreck Explorer—I’m Obsessed with the Lusitania By Nikolaus Thomas Grohne

Diving Talks: Respect for the lost on Shipwreck projects by Phil Short

Dr. Alex Brylske is the founder and president of Ocean Education International, LLC, a consulting firm specializing in marine environmental education. He collaborates with companies and NGOs around the world in creating innovative programs dedicated to coral reef conservation, citizen science, and sustainable tourism practice. He is a recipient of NOAA’s Walter B. Jones Memorial Excellence Award for Ocean and Coastal Resource Management and was the 2012 DAN/Rolex Diver of the Year. His new book, Beneath the Blue Planet, was released in fall 2022.