Latest Features

It’s About Time—The Advantages of Rebreathers in Caves

What are the advantages of using rebreathers for cave diving? It’s a question that cave instructor and author Stratis Kas, and colleague Lionel Wolovitz explore in a survey of some 500+ cave divers from around the world. Diving psychologist Dr. Laura Walton offers a professional perspective.

By Stratis Kas with Lionel Wolovitz. Commentary by Dr. Laura Walton. Lead image: Diver Ioannis Dalmiras on a KISS Sidewinder in Resell Cave, France. Photo by Caroline Negrin

In the relentless pursuit of understanding the complexities inherent in cave diving, our 2023 survey gathered insights from over 500 divers, including both anonymous contributors and named participants. We aimed to provide a comprehensive perspective with a thorough analysis of the survey data, and discussed our findings with Dr. Laura Walton, a clinical psychologist and diving instructor who founded Fit to Dive. The revelations unearthed in our exploration substantiate the intrinsic advantages that closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) technology brings to cave divers—an advantage aptly described as, “The Gift of Time.” This phenomenon not only enhances practical elements of cave exploration but also delves into the psychological dimensions of navigating the intricate passages beneath the earth’s surface.

The Rationale for Rebreather Utilization in Cave Diving

For the past ten years, my focus has centered almost exclusively on cave diving. This journey has been both a professional pursuit and a personal passion. I strongly believe that true mastery in any field comes from a combination of natural talent, consistent effort, and, most importantly, continuous practice.

Cave diving, as a scuba discipline, exemplifies the importance of practice and repetition. In my extensive experience leading expeditions and documenting them through various media, I began to realize the limitations of open-circuit scuba equipment in the unique field of cave diving. While open-circuit gear is reliable in many scenarios, the particular challenges of cave diving often require resources that traditional equipment struggles to provide. Cave diving is inherently risky, demanding a steadfast commitment to safety.

The weakest link in this system, as we all know, is the human factor. And this is where rebreather technology becomes a game-changer.

Practical Benefits and Psychological Aspects of Extended Time

When a cave diver using a conventional open-circuit system is faced with a non gas emergency—like losing the line, for example—a mental timer starts ticking, signaling the constraint of their gas supply. The stress of knowing that breathing gas is finite and rapidly diminishing can be overwhelming, often leading to additional gas consumption, stress, and even panic. In this perilous situation, the diver’s focus is primarily on finding an immediate exit, conserving the remaining breathing gas, and ignoring issues of safety or viability.

Meanwhile, they navigate a psychological descent influenced by the overarching concern that their gas supply is limited.

a) Anticipation of Stress: This stage can significantly vary. In some instances, less experienced cave divers may enter a pre-stress condition simply by being in a cave or similar overhead environment. This tendency tends to diminish as experience grows and is closely tied to the quality of cave training. However, it remains a common trait among some cave divers. For more seasoned divers, certain factors, such as a sudden and prolonged loss of visibility or a brief period of disorientation, can induce a pre-stress condition. Frequently, cave divers also question their return path, especially when facing unfamiliar cave morphology that contrasts with their penetration memory, leading them into a pre-stress phase that requires prompt resolution. Often, the most effective resolution involves reaching a familiar location in their return path, such as a navigation change marked by their own indicator.

b) Stress: Naturally, the longer it takes for divers to practically or mentally address stressful triggers, the higher the likelihood of transitioning to a full-on stress condition. This can also impact their gas consumption, creating a detrimental cycle with the possibility of potential catastrophic consequences.

c) Panic: The ultimate stage of this spiral is the uncontrollable panic zone. In this state, most divers may overlook solutions within their grasp, responding in two equally perilous ways: either succumbing to paralysis and inaction, or impulsively pursuing any available option without due consideration for equipment, direction, or teamwork. They may disregard their role in a team, hastily fleeing the scene in the hope of reaching the exit faster.

In stark contrast, rebreathers offer a significant advantage in such situations.

When utilizing a CCR, divers potentially enjoy a much larger margin before their gas and/or filter resources reach critically low levels. Their available time is primarily linked not to their gas supply but to their filter size and duration (stack time). As long as they have properly planned their bailout and stay within the distance limits it dictates, their time allowance to address a problem while remaining on the rebreather is substantially larger. In conclusion, a rebreather configuration provides cave divers with the invaluable “Gift of Time,” extending beyond mere volumetric terms.

This extension goes beyond gas volume; it significantly delays the onset of stress and panic. Rebreathers afford divers facing non-gas-related challenges the luxury of time needed to address the core issue without the added pressure of heightened gas consumption and stress. Essentially, a CCR cave diver can focus solely on the issue at hand, while open-circuit divers grapple with the dual challenges of immediate problem resolution and managing a finite gas supply for a safe return.

However, what parameters should cave divers consider when planning a cave dive to maximize the advantage of using a CCR?

Essentially, CCR cave divers must remember that their advantage is based on the fact that their limit is their scrubber duration and bailout reserves. Planning dives with the intention of reaching these limits at 100% risks nullifying this advantage in case of an emergency comfortably handled within these limits.

Awareness is crucial, as divers’ actions directly impact the operation of the rebreather unit. Managing stress and maintaining a focused mindset are paramount in avoiding issues like hypercapnia and ensuring the safe functioning of the rebreather throughout the dive. This underscores the importance of proper training, discipline, and a strong emphasis on maintaining composure.

More specifically:

a) Divers should not dive at 100% of their stack time. Doing so enters the risk zone beyond their filter limit, where the potential for hypercapnia increases, especially in stressful situations when dealing with an emergency. Relying on a low-performing, almost exhausted scrubber in a high respiratory volume situation is not advisable. CCR cave divers who do not reserve additional stack time risk relying solely on their bailout, nullifying their valuable CCR time advantage.

b) Divers should not dive at 100% of their bailout reserve. CCR diving provides a significant extension of time, resulting in a distance extension allowing for progress and permanence in a cave. But not following a conservative plan when calculating their bailout (by adding a reserve to it) also nullifies their CCR advantage. They would have to rely on their bailout, which is nothing more than an open-circuit option (Note: not valid for dual rebreather bailout).

As we’ll explore in the survey, not all CCR cave divers plan in a way that maximizes their unit’s potential for additional time allowance.

CCR CAVE DIVING SURVEY, November 2023

[Editor’s Note: Though the authors use a non-random sampling method, which can introduce certain types of bias, they are transparent in their approach, and are able to tease out some interesting findings.]

a) The Target Group

Our survey was structured with two distinct yet connected groups of respondents.

Approximately 20% of the 500+ responses were obtained from a carefully curated list of esteemed CCR cave divers, explorers, instructors, and dedicated divers known for pushing the boundaries of their craft. This aspect of the survey was crucial as it provided insights into the practices of the “elite.” I personally reached out to them and solicited their responses under their own names, allowing me the opportunity to potentially quote them (with their permission) in this article.

The majority of the responses, constituting the remaining bulk, were gathered through an anonymous, open survey disseminated across various channels, including Facebook pages and my own page, @stratiskas_adventures. The decision to cast a wider net was deliberate, and I strategically selected groups that graciously permitted me to publish the survey on their pages—special thanks to them. These groups were specifically focused on CCR, CCR Cave, or at least cave diving, ensuring a more targeted audience. Both groups of participants were asked to complete the survey

Even if the description of the survey was not very detailed when advertised, more than half (58.5%) of the target group completed the survey. The source was mostly based on Facebook pages (73.4%) and the remaining from direct links (26.6%). The vast majority (87.9%) completed the survey in 1-5 minutes as expected.

b) The Results.

Our survey was set up with a series of questions that build on each other, crucial for our analysis.

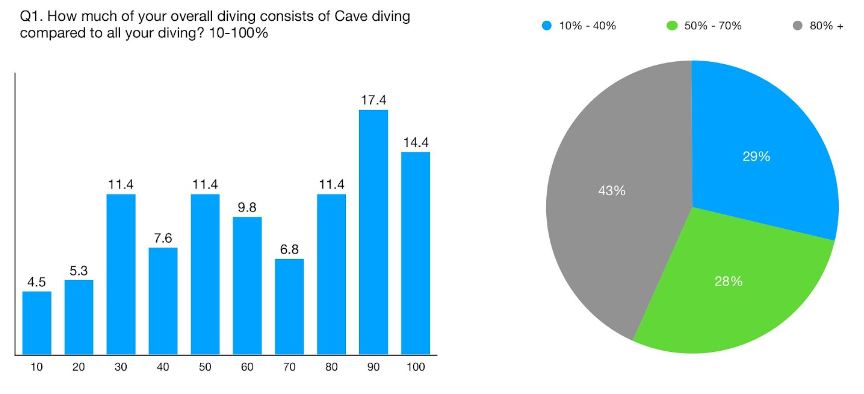

In the initial question, my objective was to determine the extent to which cave diving contributes to the overall diving experiences of the surveyed individuals, all of whom were cave certified. This approach helps filter out those for whom cave diving plays a minor role, ensuring a more focused survey. The results revealed that approximately 45% of respondents engage in cave diving for at least 80% of their overall diving, and more than 70% practice cave diving for at least 50% of their total diving experiences.

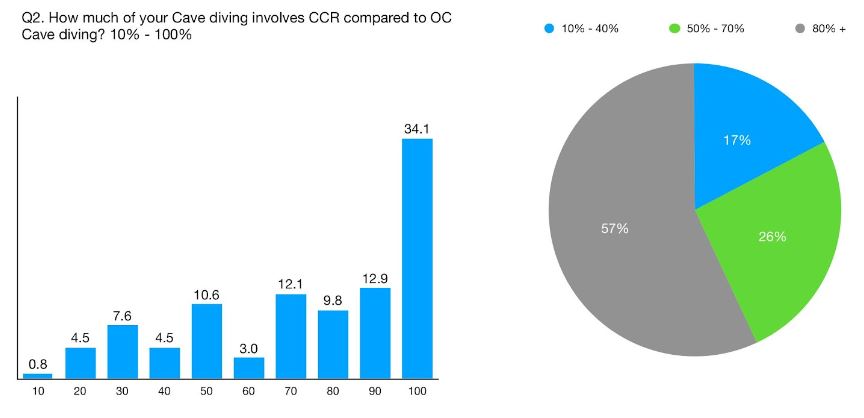

2. The second question follows a similar pattern, inquiring about the proportion of cave diving conducted using a rebreather (CCR). The results indicate that approximately 60% of respondents practice CCR diving for at least 80% of their cave diving, and 85% practice CCR diving for at least 50% of their cave diving experiences. (Note that the metrics in the x-axis shown below represent ranges; 0-10%, 11-20%, 21-30%, etc. except for 100%-almost everyone is a CCR cave diver at least on occasion.)

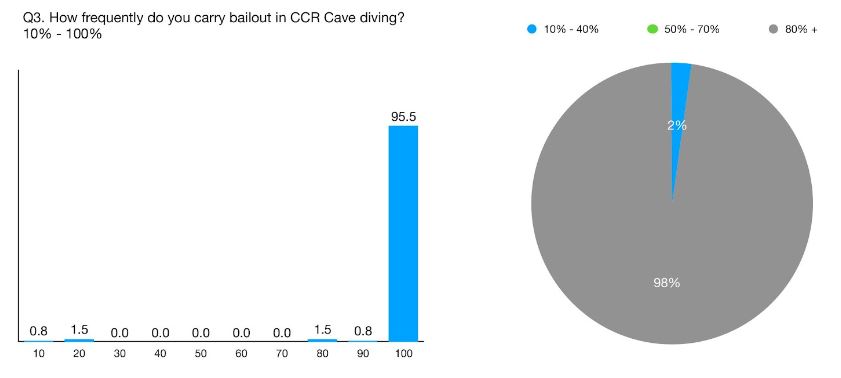

3. The next query focused on bailout. As expected, almost all CCR cave divers carry bailout, but a small percentage (around 2%) sometimes don’t. While this isn’t the place for a deep analysis of why all units can fail, it’s surprising to see any CCR cave diver without one.

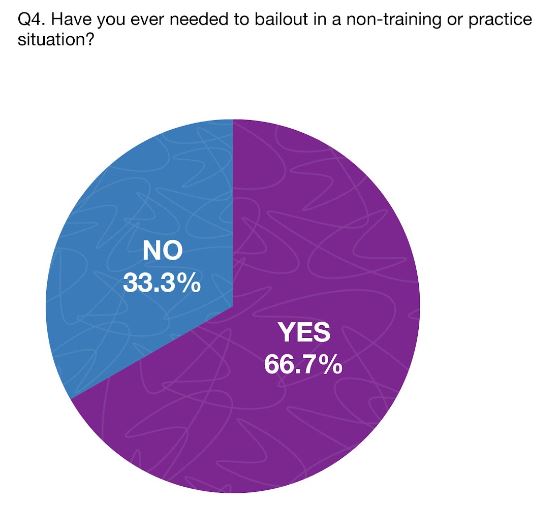

4. A full 66.7% of respondents said that they actually needed to bail out in a real situation, not just during practice or training. This emphasizes the crucial need to always carry bailout when on a CCR. The data reveals a shift in attitude within the CCR community, moving away from the old-fashioned “never bailout” mentality. CCR divers now openly admit the need to bailout, often more than once, without feeling guilty or ashamed. In my humble opinion, adopting the motto “if in doubt, bail out” is a safer choice, resolving issues with the security of being on a safe gas at all times.

In the upcoming series of questions, my aim was to understand how rebreathers were utilized to extend dive time in case of an emergency.

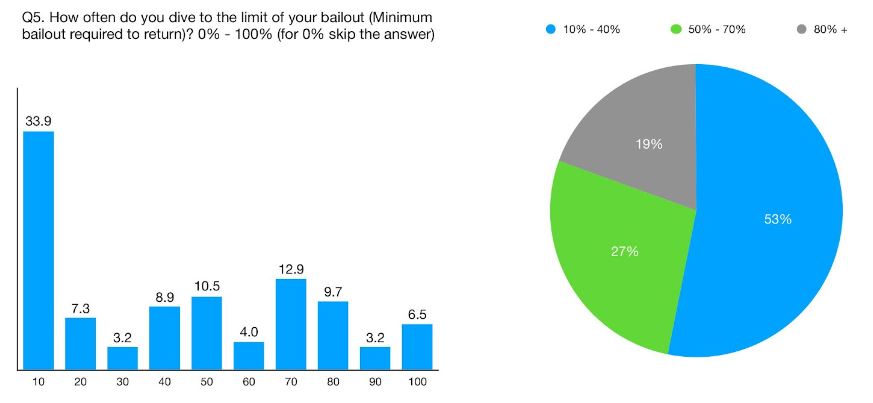

5. Initially, I inquired about the frequency with which divers approach the limits of their bailout plan without incorporating an additional reserve. This involves calculating only the minimum return gas required for the planned dive. The results show that less than 20% of all rebreather cave divers consistently practice planning their bailout needs to the bare minimum. Conversely, more than 50% of rebreather divers either never or very rarely dive to their bailout limit, effectively enhancing not only safety in gas terms but also preparing for a possible extended dive time in case of non-gas-related emergencies, leveraging the advantage of being on the unit.

6. Following the preceding question, I delved into the concept of a conservatism margin added to the minimum bailout plan, if applicable. This was intended to scrutinize the actual mindset surrounding rebreather utilization, providing an additional advantage to the user not only in the traditional sense but also as a generous “time extender” in the event of a lost diver or other non-direct gas emergencies in a cave environment. When rebreather divers plan their dives with the intention of reaching the limit of their bailout, strictly allowing for the minimum return gas required, they are unable to fully leverage the additional supply that rebreather use can offer.

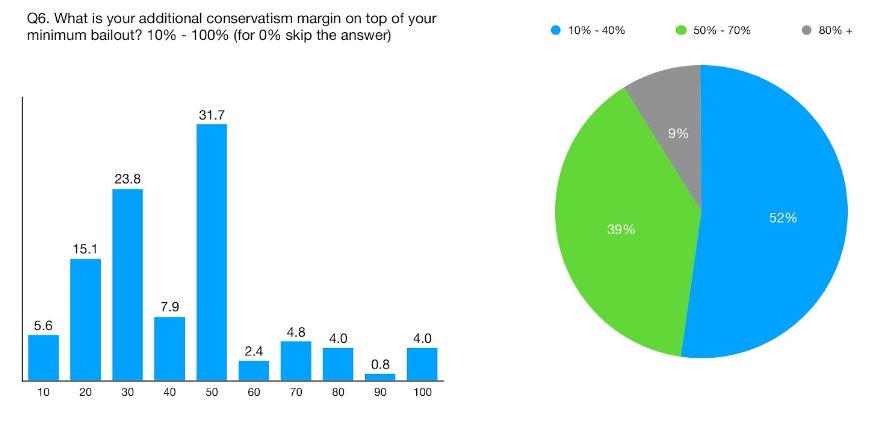

Effectively, this practice turns their dive into an open-circuit dive in case of a bailout. The results reveal that more than half of rebreather cave divers plan for anywhere between 10-40% of additional bailout on top of their minimum return gas needs, with a substantial percentage (24%) utilizing 30% of additional bailout, adhering to the traditional rule of thirds. Another significant portion (32%) opts for a 50% increase in bailout reserve, reflecting the rule of fourths—an approach to cave diving gas management that, while less traditional, is often appropriate. Only a minimal percentage (less than 10%) indicated that they double their reserve when planning a cave dive.

The next question focused on how much of the total calculated stack time divers allocate as a safety margin when planning a rebreather cave dive. If the dive is planned to reach the actual scrubber limit by the end of the initially planned dive, it provides little to no margin for an actual extension of the time spent in the cave to address problems while on the unit. Effectively, this situation once again transforms the dive into an open-circuit dive, thereby eliminating the advantage of using the rebreather itself.

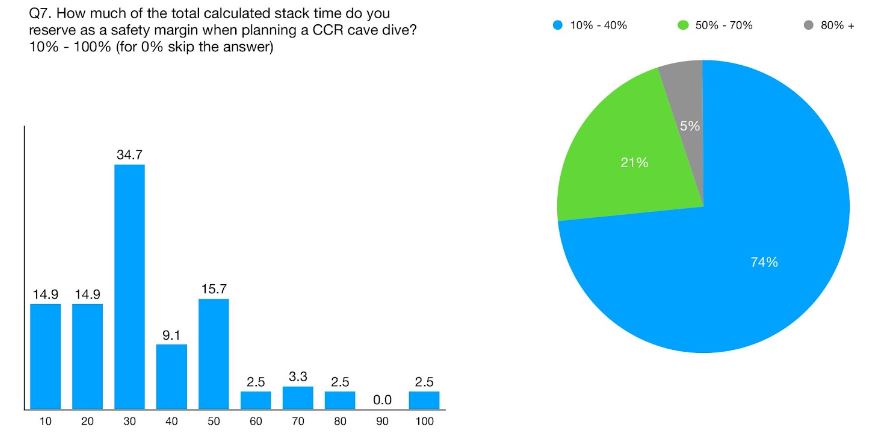

7. The survey results reveal that approximately three-fourths of all rebreather cave divers reserve anywhere between 10-40% of their maximum stack time as an emergency reserve when planning a cave dive, with 35% opting for the 30% response, reflecting the comfort that cave divers find in following the rule of thirds. A substantial portion (20%) reserves anywhere between 50 and 70% of their stack time. Note: The fact that 2.5% answered that they reserve 100% of their stack time is intriguing, to say the least.

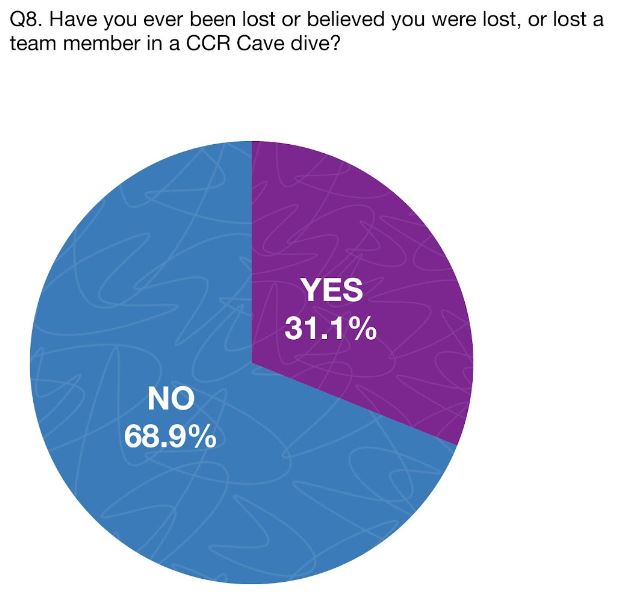

8. The subsequent question inquired whether respondents had ever gotten lost, believed they were lost, or lost a team member during a closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) cave dive, necessitating an extension of their planned dive time. The results revealed that more than 30% of all rebreather cave divers have encountered one of these conditions at least once in their diving experiences. In such instances, a meticulously planned and conservative bailout strategy, along with a calculated stack time, would have allowed them to approach and resolve non-gas-related emergencies with greater composure.

The survey also indicates a shift in attitude among cave divers: a departure from the macho “never making a mistake” archetype (concealing errors behind a façade of infallibility) to a more realistic and humble approach where divers openly discuss their mistakes to prevent repetition and encourage a culture of shared learning. It is a recognized fact that frequent cave diving increases the likelihood (as seen in at least 30% of cases) of encountering situations where one believes they are lost in a cave or experiences team separation. This prevalence underscores the significance of thorough mental preparation and proper emergency planning with adequate gas reserves for all cave divers. The inclusion of additional bailout margins and stack time conservatism emerges as a critical component of a well-rounded cave dive plan in order to address the challenges posed by unexpected situations.

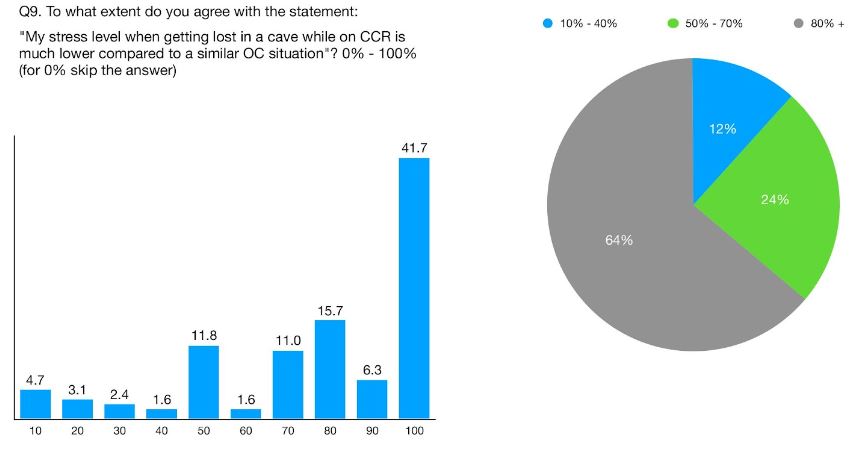

9. Question number 9 aimed to gauge the extent to which respondents agreed with the statement: “My stress level when getting lost in a cave while on CCR is much lower compared to a similar OC situation.” The results could not be clearer. A significant 64% agree with the aforementioned statement 100%, and an additional quarter of all survey participants—bringing the total to almost 90%—believe that at least half of their stress is reduced when lost in a cave while on a rebreather compared to the same situation while on open-circuit.

These figures, however, do not precisely align with the findings from the earlier questions, indicating that some cave divers who derive comfort from using a rebreather may not effectively plan for its full advantage. It is conceivable that this subset of divers answered negatively in the preceding question (Question 8) and, therefore, may not have firsthand experience with the emergency itself. We trust that this article and the survey results serve as an eye-opener to the significant safety benefits of utilizing a rebreather in cave diving scenarios, as highlighted in Question.

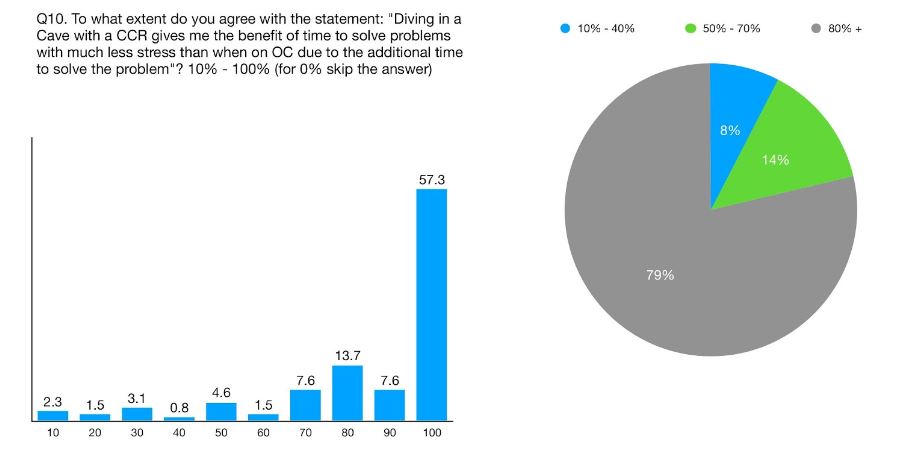

10. The final question aimed to assess the degree of agreement with the statement: “Diving in a cave with a CCR gives me the benefit of time to solve problems with much less stress than when on OC due to the additional time to solve the problem.” Similar to Question 9, this sought to draw a conclusion and ascertain if the observed trend in recent years reflected the broader sentiments and practices within the community. Notably, approximately 80% of all survey participants express the belief that the use of rebreathers in cave diving provides them with a time advantage compared to open-circuit diving. Conversely, a minimal 8% of participants do not perceive a significant advantage to the use of rebreathers in cave diving in terms of the time allotted to solve problems. This finding aligns with a comparable percentage of respondents who plan for only 10%—or less—of their stack time as an additional reserve, effectively diminishing the advantage of using a rebreather in cave diving.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of our comprehensive rebreather diving survey shed light on the intricate dynamics of cave diving with closed-circuit rebreathers (CCR). A staggering 45% of divers immerse themselves in caves for more than 80% of their diving experiences, showcasing the profound allure of subterranean exploration. Additionally, a substantial 60% of divers opt for the CCR’s enhanced safety and efficiency when navigating the intricate passages of cave systems. The survey revealed that an overwhelming 98% of CCR cave divers conscientiously carry bailout, underlining their commitment to safety protocols. Notably, 70% of those who carried bailout encountered real-life scenarios demanding its use, reinforcing the importance of preparedness in the unpredictable underwater realm.

Furthermore, our data unveiled the prudent nature of CCR cave divers, with 35% never pushing their bailout plan to the limit and an additional 20% doing so only infrequently. Strikingly, 80% of these divers carry between 20-50% additional bailout beyond the minimum requirement, showcasing a commitment to thorough contingency planning. The survey also illuminated the strategic approach of CCR cave divers, as 90% reserve between 10-50% of their stack time, providing a crucial safety net in the event of unforeseen challenges.

A poignant revelation surfaced regarding the psychological aspect of cave diving with CCR: 30% of divers admitted to moments of feeling lost or experiencing team separation scenarios, yet persevering through these situations.

Encouragingly, 65% strongly agreed that the stress levels associated with getting lost in a cave while on CCR were significantly lower than in a similar open-circuit (OC) scenario. Most notably, a resounding 80% concurred that the “gift of time” afforded by a CCR in cave environments empowered them to tackle challenges with reduced stress, affirming the unparalleled advantages of rebreather technology.

“This survey unequivocally demonstrates that the ‘gift of time’ is not just a concept but a tangible reality for us. It’s the difference between panic and problem-solving, making every dive a testament to the profound impact of rebreather technology on our underwater experiences.”

In the words of a seasoned CCR cave diver, “This survey unequivocally demonstrates that the ‘gift of time’ is not just a concept but a tangible reality for us. It’s the difference between panic and problem-solving, making every dive a testament to the profound impact of rebreather technology on our underwater experiences.” This conclusive sentiment encapsulates the essence of our survey findings, reaffirming that CCR cave divers genuinely embrace and benefit from the precious gift of time in their explorations beneath the earth’s surface.

A Psychological Perspective from Dr. Laura Walton

This is an intriguing survey, which raises valuable questions for research and diving training. Although the non-random sampling method used for the survey risks several kinds of bias and means there are issues with generalization of results to the target population, the approach has its uses. The authors have leveraged the advantages of the method successfully: reaching a highly niche group and achieving an impressive response rate. The element of purposive sampling, where the researcher reaches out to individuals to gain insight to a particular area of interest, means that the results are likely highly skewed towards expert opinion. So, although caution is needed in the interpretation, this exploratory project provides a substantial contribution to understanding of this small and under-researched population.

Focusing on the authors’ core conclusions relating to time and stress-level, I would tend to agree this is a key finding. Their statement that perception of sufficient time is the “difference between panic and problem-solving” is logically based on their experience. It makes theoretical sense. I often present panic as triggered due to a combination of three over-arching components: the presence of stressor(s); a mismatch in readiness for the situation in terms of skills or equipment, and; a difficulty in regulation of emotion and/or attention.

Given the target group, I’d like to extend beyond panic to include any overwhelming stress response. In this group, which is low in novices, it’s reasonable to assume that panic is much less likely. It is still of course possible that an overwhelming problem can push a diver into a stressed, “survival mode” state, but my own theory is that when this happens with an advanced diver in a cave, fight and flight reactions are skipped over, throwing the diver straight into a frozen “fright” state, possibly dissociation. (Either that, or a level of acceptance that is beyond most people and permits calm.)

Whatever the presentation, the stimulus for those unworkable states happens when the demands of the situation/event exceed the diver’s capacity to cope. This can include the ability to solve problems in terms of equipment issues or skill, as well as ability to regulate response to stress.

For any diver, whether it’s gas supply, time to decompression, or stack capacity, the time available before an absolute need to surface is relevant. Where it is insufficient for the dive, then that could be a mismatch in readiness. In addition, with open circuit, there is a shorter supply, as well as more variability in how long that gas will last (due to SAC rate, and potential for this to change as a result of physical or psychological stress). This means a potential for uncertainty. Uncertainty is a major driver of stress and anxiety. Talking to the authors, it is clear that CCR not only extends the available time, it can also (given proper procedures and in combination with bailout option) potentially reduce uncertainty significantly.

It would be reasonable to argue that reduction of uncertainty, an increase in perceived agency (the ability to do something), can have a large impact on subjective stress-level.

Of course, this benefit could be eroded for divers new to CCR, as the task load involved in using new equipment and acquiring skill is likely to increase stress for a time. And there are other uncertainties introduced by CCR compared to OC. Some divers may feel more stressed by the potential for the known hazards than the limits of OC gas supply. This is where the sampling method is relevant, it would be interesting to notice whether relative abundance of time has such significant stress-lowering properties for all within a target population.

Other explanations could be posed. For example, a survey respondent who is diving in caves on a closed-circuit rebreather (particularly given that the authors selected for a subjective “elite”) is one who is highly trained and experienced in scuba diving. In conversation, we also discussed the fact that a CCR diver, due to the nature of the equipment and necessary training, would most likely have an advanced understanding of breathing and respiration in comparison to an open circuit diver. Moreover, they know that awareness and management of breathing rate is vital to a successful dive, if not survival itself. And when you regulate breathing, you also regulate emotions. So, one interesting factor here is the indirect contribution of this group’s skill in regulating both their physical and the psychological state.

DIVE DEEPER

BODI: Survey Results: The Future of Rebreathers in Scuba Diving

BODI: Expectations For Rebreather Forum 4 & A Glimpse Into The State of Rebreather Diving. The survey was conducted in March & April of 2023 among Rebreather Forum 4 attendees, presenters, exhibitors & sponsors.

InDEPTH: Cave Diving, Everything You Always Wanted To Know

Stratis Kas, a Greek-Italian professional diving instructor, photographer, film director, and author, has spent over a decade as an esteemed Advanced Cave instructor, leading expeditions to extreme locations worldwide. His impressive diving achievements have solidified his expertise in the field. In 2020, Kas published the influential book “Close Calls,” followed by his highly acclaimed second book, “CAVE DIVING: Everything You Always Wanted to Know,” released in 2023. Accessible on stratiskas.com, this comprehensive guide has become a go-to resource for cave diving enthusiasts. Kas’s directorial ventures include the documentary “Amphitrite” (2017), shortlisted for the “Short to the Point” Film Festival, and “Infinite Liquid” (2019), which explores Greece’s uncharted cave diving destinations and was selected for presentation at Tekdive USA. Kas’s expertise has led to invitations as a speaker at prestigious conferences, including Eurotek UK, Tekdive Europe and USA, Tec Expo, and Euditek. For more information about his work and publications, visit stratiskas.com.

Lionel Wolovitz grew up in South Africa where he developed his lifelong passion for the outdoors, fitness and adventure activities. He first qualified as an open water scuba diver in 2018 and is now a certified trimix open water, normoxic CCR and multistage, dpv and full cave diver. He lives in Gozo (Malta) and the UK and when not diving or freediving, he can be found running or mountain biking along the forest, hills or cliff top trails. He has a doctorate in electronic engineering and has worked for a range of hi-tech electronic product and software companies in leadership roles as Chief Technology Officer, driving technology strategy or managing large teams of engineers. He is a certified coffee nerd. He loves food, especially when Stratis cooks.

Laura Walton is a clinical psychologist and scuba diving instructor bringing together psychology and scuba diving to help people with their diving. She provides specialist psychological services for scuba divers and accessible courses. Laura has been guiding and teaching scuba diving in the UK since 2012, and is currently a PADI IDC Staff Instructor at The Fifth Point Diving Centre, Blyth, UK. Find her blog here: Fit To Dive Blog.