Photography

From Diver to Filmmaker: Carolin Negrin’s Underwonder Odyssey

Cave instructor and author Stratis Kas illuminates the journey that led to Carolin Negrin’s film debut about Greek cave diving—the four-part documentary Underwonder.

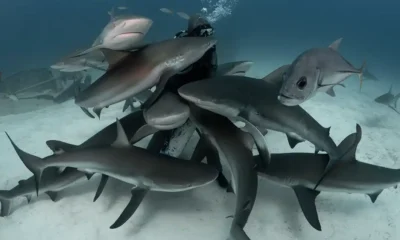

By Stratis Kas. Images courtesy of Carolin Negrin unless noted. Lede image: Vouliagmeni Cave, a new discovery. Photo by Carolin Negrin.

Crafting a good film is hard. Doing it underwater? Even harder. And I’m not just talking about the technical difficulties of underwater cinematography; I’m talking about the challenge of creating truly captivating content. This may sound strange when discussing filming in submerged caves which offer great potential for stunning visuals and so on. Filmmaking isn’t just about pretty shots. True filmmaking has to evoke emotions—often through the viewer’s connection with the characters. And that’s what makes Carolin Negrin’s first attempt as the sole underwater cinematographer (among other credits) for the upcoming documentary series Underwonder so special.

Carolin managed to translate the connection her team had on land into breathtaking (yes) but also meaningful filming. This may be one of the most special cave diving documentaries to date. The fact that it’s filmed in Greece—in some of my favorite caves, by one of my good friends—is just the cherry on top. Honestly, I approached it with huge doubt, because I know firsthand how complicated it is to create content in expedition filming.

Back in 2018, when I was set to speak at Eurotek—coinciding with the Thai rescue team’s debut on stage—I met Carolin, who had come to see the show. We chatted about our shared interests in photography, cameras, and underwater filming. At the time, I could foresee neither the bond that would develop between us nor her future in film making.

Fast forward to today, when Carolin has become more than just a friend; she’s been one of my cave diving companions across numerous expeditions worldwide. Her dedication proves that passion breeds excellence. I’m honored to feature much of her work in my latest book on cave diving, and I’m grateful to call her a true friend.

Despite our closeness, Carolin kept a surprising secret: she was working on a new documentary about Greek caves, a subject dear to me. This time, I refrained from assuming it would be like any other. Underwonder is a gem of a four-part documentary series that will captivate not only divers but also anyone fortunate enough to watch it.

In this interview, we delve into her debut documentary and her journey behind the lens; we explore the challenges, triumphs, and artistic vision that define her work. From the depths of underwater caves to the minutiae of visual storytelling, Carolin shares her insights into the intricate dance between creativity, safety, and the raw beauty of underwater caves.

Stratis Kas: Would you share the backstory behind the creation of Underwonder, your upcoming documentary?

Carolin Negrin: The story behind Underwonder is pretty interesting, especially with the hurdles of the pandemic. When diving got banned in Greece due to COVID-19, my team and I decided to make the most of our time. We started gathering data for Lake Vouliagmeni, a spot we loved diving in. One of my teammates, Andreas Kouris, who’s also a TV producer, suggested making a short video about the lake with the info we had. It was a great idea because it meant we could still dive.

We spent a lot of time underwater, capturing the cave’s beauty. Though we faced some challenges, like figuring out how to film the huge Vouliagmeni cave, we kept at it. As we saw the footage turning out well, we decided to turn it into a full documentary. With support from Cosmote, Greece’s incumbent telecommunications provider, our dream came true, and Underwonder was born.

Well, that’s a clever way to keep your passion alive. It sounds like you found a solution right when you needed it most. I can relate—I was in Greece around that time too, and I understand the frustration. Coincidentally, my new rebreather arrived just a day before the second lockdown started.

Quite a stroke of luck, wouldn’t you say?

Truly. So, what inspired your team to center your documentary around caves? And why these four caves in particular, given Greece’s wealth of options? It feels like there’s a deeper story behind the choice.

Absolutely; I’m all in on the idea that cave diving is the ultimate type of diving. Now, as for the rest of the crew, they split their love between other types of diving as well, but we definitely share a deep appreciation for exploring underwater caves.

Well, that’s precisely why they’re not joining us for this interview, right?

Exactly! You and I share the love for cave diving! The idea was to select caves that would capture the general public’s interest. As Andreas, the documentary’s producer, pointed out, people who aren’t immersed in cave diving aren’t necessarily thrilled by the sight of rocks. While cave divers may revel in rock formations, the broader audience may not share the same enthusiasm. So, we needed an approach that would resonate with those outside the community: something that would make them see underwater caves as more than just geological formations.

Our goal was to create a connection between all Greeks and anyone fascinated by Greece, igniting their curiosity about underwater caves. Through extensive research, we realized that caves serve as repositories of history, offering insights into the ancient landscapes of Greece. They provide a window into the past, revealing how the land [we now recognize] appeared tens or even hundreds of thousand of years ago. So, we meticulously chose caves with geological significance—ones that could unveil Greece’s ancient narratives.

That’s why our selection included Vouliagmeni, Amphitrite in Antiparos, the Elephant Cave in Crete, Chania, and the remarkable caves of Diros in the Peloponnese. Each of these sites offers a glimpse into Greece’s rich geological and historical heritage, making them ideal subjects for exploration and storytelling in our documentary. We were lucky enough to have the ability to work with talented people that created 3D models of Greece’s past based on our research and findings.

Were there any new discoveries that emerged as a result of your exploration?

Without giving too much away, I can confidently say that our expedition yielded results not previously available to scientists. However, I’ll refrain from divulging too many details because I believe it’s best experienced firsthand by watching the documentary.

In research, sometimes the aim is to validate a hypothesis, while other times it’s about discovering the unexpected. Can you elaborate on your approach during the expedition?

At Vouliagmeni Cave, our initial goal was to substantiate a hypothesis —particularly concerning the cave’s deepest section. In the process, we unearthed data previously unknown to scientists via both imaging and other revelations, which I won’t spoil. Regarding Amphitrite Cave, we collaborated with Professor Manolis Vassilakis [Geology Dept. of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens] to date formations—a first for this site. However, in Diros and the Elephant Cave, our missions were mainly to verify existing scientific findings, offer images that spoke to those, and—like I mentioned before—recreate the past with 3D technology.

Your journey from casual diving to crafting a documentary seems to have evolved organically. How does it feel to see this transformation from a simple dive excursion to producing tangible results in the form of a film?

Honestly, it’s been surprising for us as well. We didn’t expect the unexpected things that happened during our journey. Seeing our project go beyond just diving and achieving something meaningful has been really amazing.

Indeed, this is the essence of scientific inquiry. Every project carries the potential for discovery or, conversely, the realization of no tangible outcomes. Even when faced with null results, it’s still a significant outcome, albeit a disappointing one.

That’s really important. Success sometimes makes us forget about failure, but failing is a big part of getting things done. It’s how we learn, change, and, finally, succeed. From success you get joy, but from failure you get lessons. Sometimes I can’t tell which is more important.

Absolutely, and that’s a significant aspect to consider. It’s not merely about failure; rather, it’s the level of satisfaction derived from obtaining results while investigating a hypothesis. Even if the outcome disproves the hypothesis, it’s still a successful scientific exploration. Yet, the impact on the general public may lack the dramatic appeal associated with affirming an hypothesis.

It’s not just about theories or results. It’s about how being there in person impacts you deeply. Take the Elephant Cave in Crete, for example. It’s named because they found elephant bones inside. Now, you might wonder, “Elephants in Greece? Especially in Crete?” These questions might not occur to you until you’re actually there, seeing the evidence yourself. Being in these places sparks curiosity and makes you ask questions. And what we’ve learned is that diving and science go hand in hand. Scientists often need divers to reach places they can’t reach on their own. So, when you’re diving just for fun and then realize how important your work is—whether you’re collecting samples or taking pictures—it’s really satisfying and honestly, quite surprising.

As the documentary’s underwater filmmaker, you face challenges reminiscent of an earlier era, where factors like light, camera type, and stability mattered more than they do today. Contrastingly, land-based filming benefits from modern technology’s safety net. How have recent advancements in underwater filmmaking technology changed the way you work?

New camera technology means we don’t need as many lights underwater. Cameras with high ISO sensors can film well even in low light. This has been particularly beneficial in illuminating vast spaces like those found in Vouliagmeni cave where working with older sensors, for example, would have been insufficient. Also new, stronger, and more affordable lights became available and that has elevated our ability to work underwater. But at the end of the day, it is not about technology. [Learning] underwater photography and videography is like re-learning everything from the beginning. The basis of photography, the light, has its own new rules underwater; as you yourself very well know.

Can you outline the primary challenges you faced as a filmmaker in each of the caves featured in the documentary?

Filming in Vouliagmeni cave posed some big challenges due to its huge chambers, which made it hard to light up the whole area and show its size properly. Even with extra lights and help from other divers, capturing the cave’s grandeur was tough. Plus, entering the cave at 36 m/118 ft depth meant we had to spend a lot of time decompressing after each dive, which added to the logistical issues and limited our time filming.

Filming in Amphitrite cave, on the other hand, was a bit easier. It’s not as deep, and the chamber size is more manageable, so lighting it up was simpler. Also, the cave’s bright formations helped brighten the space. But because the cave opens to the sea, we had to deal with unpredictable weather, which limited our diving time during our week-long shoot. Still, once inside, Amphitrite was great for filming with its beautiful formations and easy layout making it enjoyable to work in.

The Elephant Cave in Crete had its advantages for filming, too. Its shallow depth and air pockets created interesting reflections. But during filming, two of our team members were unavailable for a while, leaving just Giorgos and Andreas to handle lights and modeling. With limited manpower, we had to get creative, using steady lights and clever positioning to make up for it. Despite the cave’s good conditions for photography and filming, dealing with logistical issues was tough. We’re all passionate about cave diving, but sometimes other commitments get in the way, causing unexpected challenges during shoots.

Okay, but some of these challenges seem more related to the production organization rather than inherent cave specifications.

Definitely. Where the cave is and what it’s like can make things tricky. For example, Vouliagmeni Cave in Athens is easy to get to, but it’s super deep, so not everyone can dive there. The location and how the cave is set up really affect what challenges we face as photographers and filmmakers.

Then there’s Diros. Getting permission to dive there was tough since diving is not allowed in the caves. We got the permit, but we could only do two short dives. Plus, one of our cameras had some issues, so we had to film with just one. We had to be spot-on with everything because we had no room for mistakes. But even with all that, Diros is incredible, and we managed to get enough footage for a full episode. And I can tell you, because of the restrictions on diving and filming in Diros caves, the footage you are going to see is unique.

courtesy of Cosmote TV.

Great! How did your team come together?

The first member I met from the team was Andreas Kouris. Our paths in diving were similar until I decided to become an instructor, which he found a bit crazy. Luckily, he was just as dedicated as me when it came to tech, cave, and CCR diving. I encouraged him to try cave diving, and he influenced me to switch to rebreathers. Then, we met George Vandoros, the team’s only dedicated professional. He introduced us to cave diving and CCRs, and we’ve been diving with him for a while. Through George, we met Vasilis Zografos and Antonis Krentz while diving at Vouliagmeni Lake, and we naturally formed a team. It wasn’t a decision; it just happened when we found people with the same passion, mindset, and training. I don’t think the term “friends” really applies to members of a cave diving team. We might not hang out together socially, but our bond is unique. How many of your friends have you thought about saving in a life-threatening situation? I’ve thought about that for each one of them.

Let’s talk about teamwork. How did you manage to cultivate effective collaboration and communication in such a demanding and specialized environment, especially considering your role as the newcomer leading a team with prior experience? It seems you were tasked with multiple roles—from actor to filmmaker. How did you navigate these diverse responsibilities while ensuring seamless coordination with the rest of the team?

The big challenge with this project was doing a lot of different jobs. I had to work with the production team, do all the filming underwater—which means directing, operating the camera, and more—and also be a cave diver. Every single one is a difficult task on its own. It was like juggling a lot of balls at once. The director had a vision, but it didn’t always match up with what’s practical for underwater filming or cave diving. So, I had to make that vision happen while always keeping in mind the safety of the team and the challenges of each environment. Briefing the team would always take place on land because communicating underwater is practically impossible at that level. I would give them detailed instructions before the dive, but most of the time, we had to change plans on the spot because not everything was predictable. I can tell you rebreathers help a lot with that because you can communicate some basic words. Except for me! Apparently, I talk like a duck in the loop, so no one can understand me… I can hear myself on every video, but no one from the team would understand me underwater. That remains one of the mysteries of nature.

Amfitriti, Antiparos, Underwonder documentary backstage

That’s an interesting approach! Can you explain how you determine your goals for each dive, and how you prioritize them?

We had a rule: only three tasks per dive. More than that was just too much. Since I was the only one handling the camera, I had to make sure to capture the whole story from different angles. That meant I had to keep moving to get close-ups, wide shots, and different views. Getting all these shots meant redoing some parts, making each dive more complicated. In deep dives like in Vouliagmeni, making it out safely from depths like 130 m/427 ft inside the cave was the most important thing. Filming was really very low on my priority list.

Obviously an ideal thing to do is recruit support divers—people who often accompany filmmakers to assist them throughout the dive. We’ve employed this strategy in previous projects, ensuring there’s always someone alongside the filmmaker for support.

That sounds ideal. Unfortunately, it’s not always feasible, especially at significant depths.

How did you manage the contrasting pace of underwater filmmaking, which often requires swift action due to limited time and technical constraints, with the slower pace typical of above-water production?

Okay, so there are two aspects to this. Firstly, as a technical diver, planning is essential. You have to consider every detail, from gas supplies to camera batteries, and create a thorough plan that covers all contingencies. This part came naturally to me because it’s integral to technical diving.

However, the real challenge lies in understanding that you often have only one chance to get the shot. For example, when we dived to 130 m[/427 ft] or explored specific areas in Diros, there was no room for error. We had just one dive, one opportunity to capture what we needed.

I’ll share a story from my days as a professional photographer. In wedding photography, you also have just one chance to capture those precious moments. There’s no room for mistakes. This experience taught me the importance of being quick on your feet, both physically and mentally, and finding solutions to any challenges that arise. It’s all about capturing those fleeting moments perfectly because there are no retakes. I did it for two years, and let’s just say it aged me a bit. It’s an experience I’m glad to leave behind, but I’m also appreciative of that very important skill for underwater photography and cinematography.

Can you share any hidden details that viewers might not see, especially during just a simple view of the documentary?

Absolutely. Teamwork behind the scenes is essential but often goes unnoticed. In the documentary, you see us diving deep into Vouliagmeni cave, but what you don’t see is the extensive support team behind it all. And there are divers like Said ElSoueidi and Ioannnis Dalmiras who are not mentioned a lot, but have both modeled for me for countless hours to get some of the results you see on film.

Behind the scenes of the 130 m deep dive in Vouliagmeni Lake, additional divers like Nikos Pitaras, Ioannis Moraitis, Haris Christidis, Antonis Iordanoglou, Panos Vranas, and Ioannis Tzavelakos provided crucial support. They helped carry tanks in and out of the water and ensured surface support and safety. Their assistance allowed us to focus on diving and filming, making the experience relaxed despite the challenges.

During the six-hour dive, the support team ensured that we had everything we needed; they even managed the logistics of multiple tanks required for decompression. Their assistance was instrumental, enabling us to continue filming seamlessly throughout the dive. The poignant moment captured in the documentary, where George and Andreas congratulate each other upon completing the decompression, encapsulates the culmination of our remarkable journey made possible by the unwavering support of our team.

Diving support is critical not only for safety but also for comfort in this case.

Yes, indeed. The corrosive nature of the water in Vouliagmeni Cave necessitates that tanks cannot be left there. Therefore, everything had to be placed and removed on the same day of the dive. Without support, it would have been impossible to accomplish this.

Carolin, with your extensive experience as a deep diver, a rebreather diver, and now also as a filmmaker, what aspects of the caves featured in the documentary do you find most captivating? I’m particularly interested in the sensations you experience.

It’s fascinating how I am drawn to the darkness and tranquility within the cave. Balancing my personal inclination towards darkness with the audience’s expectation for well-lit footage presented a unique challenge. While I love the immersive experience of darkness, [the] production [team] often preferred well-illuminated scenes to grasp every detail. Striking a balance between conveying the cave’s atmosphere authentically and meeting production expectations was quite a task.

A darker and more dramatic aesthetic could indeed describe your signature style, setting your work apart. Is it a unique approach that reflects your personal connection to the environment ?

Definitely. I’m sorry for the fellow photographers. I’m not a fan of cave photos you see from places like Mexico, where everything is brightly lit, showing every single detail.They don’t capture the real experience of being a cave diver. We don’t have tons of lights illuminating everything. Instead, our dives are mostly in the dark, with just our dive lights cutting through it.

I get why people want to see all the details in cave photos, but for me, it’s more about conveying the true feeling of cave diving. So, in the documentary, you’ll see some parts with lots of lights—that’s what the production team wanted. But when you see darker scenes, with just a bit of backlighting, that’s my touch.

Looking back on your experience filming this documentary, what changes would you make if you could start the project again today? Would you approach it differently?

I would definitely ask for more time. The challenge with photography or videography is that you always have this feeling that things could be slightly different. From my experience, I’ve noticed that each time I revisit a cave, my results improve. If I film over one day, the result is ok. On the second day, it’s even better, and by the third day, it’s really good. So, what I really need is time. It’s funny when I realize that this is what matters most in tech diving too.

Do you think that sometimes the initial experience can’t be replicated, and it’s essential to build up to better results over time?

In underwater photography, spontaneity doesn’t really work. Especially when we’re talking about achieving specific goals. Planning is key.

So, stepping back a bit, you’ve been diving for fun and for exploration. Now, you’re diving for filming, and each experience is quite distinct. Could you explain to us the main differences you’ve observed among these three experiences?

When I go diving, whether it’s in a cave or open water, I usually have a series of things I plan to do. But when I’m working on a project, there is a “shopping list,” which isn’t just mine—it’s given to me by a director or production team. Diving as a hobby is different from diving for work. It changes from something I do for fun to something that demands specific results. This change adds stress and takes away some of the fun of diving.

How do you approach balancing results and safety in underwater productions? Do you sometimes need to veto certain elements or propose alternatives to ensure safety while still achieving the desired impact for viewers?

Because our director Kostas Karydas wasn’t familiar with caves or cave diving, he gave me ideas and images to produce, leaving the execution to me. I had to decide everything from location to lighting, divers’ roles, and even simulate challenging conditions like poor visibility. I had to improvise solutions, since no one else from the filming crew understood what was needed.

Got it. Sometimes, in filmmaking, we need to recreate visuals in a controlled, safe manner. As long as we’re not deceiving the audience, it’s acceptable. Using some specific visuals to enhance the narrative or poetic aspects of the film.

In this documentary, we embarked on an expedition with a specific goal. For experienced cave divers, the process of preparation, diving day, and results would be familiar. However, since the documentary is not just for cave diving enthusiasts, we needed to make it accessible to those unfamiliar with the sport. We included visuals to help viewers understand what we were doing underwater. For instance, although we didn’t encounter zero visibility in Vouliagmeni Cave, we filmed a scenario to illustrate the potential dangers of cave diving to those who may not be aware of them.

Did you encounter any challenges in preserving and respecting the natural environment of the caves? Were there instances where you had to restrict your actions or alter your plans to avoid endangering the environment?

Our priority has always been to ensure the preservation of the cave environment during our dives. We’ve been mindful not to cause any harm. However, there was a challenging moment when a researcher from the university we were collaborating with asked us to collect samples from Amphitrite cave. One sample had to be from the deeper section, while the other required breaking a part of the cave formation. It sparked lengthy discussions among us. While we understood the scientific necessity for such actions, it was difficult for us ethically. Despite the discomfort, we proceeded cautiously, ensuring that we captured the necessary footage meticulously. It was a tense moment, as we knew we only had one opportunity to get it right without causing further harm to the cave.

You’ve been cave diving not only in Greece but around the world, for which I think I deserve at least a 50% motivator credit for that. But that’s another story! When comparing Greece’s underwater cave systems to those in other parts of the world, what unique geological or general aspects stand out to you as particularly captivating for divers and filmmakers? Do you find Greece as a destination enticing, or are there specific caves that you find especially intriguing?

You get 50% of the credit, and Said ElSoueidi, who moved to Mexico, gets the other 50%! Well, the thing about Greece is that it’s packed with caves, lots of them. But they’re not all the same. You can dive in Vouliagmeni near Athens, then hop over to Sinji Cave just two hours away, and it’s a whole different world. Take a boat trip for three or four hours, and you’re at Amphitrite, yet another unique cave with its own set of formations. So, I just mentioned a warm, huge cave; a cold, narrow spring; and a sea cave full of decorations.

That’s the fascinating thing about Greece. Most of the caves are made of limestone, but each one is totally different from the next. Unlike other popular “cave destinations,” where you’ll find more of the same, Greece packs in a diverse range of caves all within close reach of each other.

Honestly, I have something to say about Greek caves. Cave diving isn’t well developed here. While the caves themselves are accessible, getting to them isn’t straightforward.

But it’s mostly a logistical issue because the caves aren’t near Athens. They’re mostly in the rest of the country, where logistical support is scarce and often highly seasonal.

Exactly, there’s no support. Cave diving in Greece isn’t easy.

Alright, as someone who knows the ins and outs of diving and filmmaking in Greece, what advice would you give to cave divers looking to explore the caves here?

Okay, let’s break it down. In places like Mexico or France, diving into caves is like a walk in the park. You find a dive center, they sort you out with all you need, and off you go. Simple. But in Greece, it’s a bit of a different story. Here, you’ve got to know the right people who know their way around the caves. It’s not as straightforward. Greece might be modern in many ways, but when it comes to cave diving, it’s a bit like going on an expedition to a remote place like Madagascar. You need someone with the inside scoop to make it happen.

Okay, do you think this also means it’s hard to rent equipment?

You can rent equipment, but you have to know who to ask. You need someone to guide you, show you where to go, and tell you who to talk to. It’s all about getting support and help with the logistics. That’s the challenge. You can’t just go online, find all the info, rent your tanks, and start cave diving.

Let’s talk about the film. What sets Underwonder apart from other cave or underwater documentaries you’ve watched?

Our director wanted something more dramatic, adding suspense to show the danger of cave diving. And yes, it’s true, cave diving is risky. But we wanted to present it calmly, objectively. The truth is, we train a lot to minimize the risk. We never feel like we’re going to die when we go cave diving. We enter the cave with a clear understanding of what we need to do to stay safe. So, we approach the activity calmly, knowing we’re prepared for the task at hand.

So, you’re suggesting that Underwonder takes a more objective approach to these environments, steering away from the typical dramatic portrayal of cave diving as an extremely perilous sport, right?

The thing is, it’s super risky, which is why we’re doing everything possible to cut down on the danger. We’re trying to highlight in the documentary that if you’re ready and well-trained, and you make smart choices, you’ll likely come out okay, even in tough situations. And that’s not just about cave diving; it applies to life in general. That’s the message we’re aiming to get across.

When watching the film, viewers might wonder about the group of people featured. In the first episode, it’s not very clear if they’re friends, occasional diving companions, or have deeper connections. It’s left ambiguous. However, one thing that stands out is that, aside from perhaps George, they don’t fit the stereotypical image of adventurers. They seem quite ordinary. Was this intentional? Did it happen naturally?

If you attend a tech diving conference, you’ll see that most participants, especially those into cave diving, are typically over 40 and have average builds. Being fit is important, but extreme fitness isn’t necessary. What sets them apart isn’t their appearance, but their mindset and knowledge. Economic status also plays a role because these activities require significant funds, especially if you’re into underwater filmmaking. So, it’s not by chance that the people in the documentary look ordinary; they’re representative of the tech and cave diving community.

Absolutely. There’s a famous quote from Richard Harris about being the last picked for sports teams but the first called for the Thai rescue. It makes you think, doesn’t it? Perhaps introverted individuals tend to develop these special skills quietly, making their abilities less obvious to those around them. What do you think?

Definitely. Cave diving attracts a unique type of person. It’s different from regular diving. To be a cave diver, you need specific traits. I’m not sure if being introverted is one of them, but now that I think about it, most of the passionate cave divers I know are introverts. What I can say for certain is that we enjoy solitude. We prefer quiet and don’t always feel the need to talk. We believe in solving problems on our own. So, yes, we’re a unique bunch. I don’t think everyone can become a cave diver. It’s not like regular training or effort can guarantee safety in cave diving. It’s a challenging pursuit, and not everyone is cut out for it.

Alright, let’s wrap up with some ending statements. Simple answers.

Is cave diving the safest type of diving?

It can be.

Cave diving—it’s a team sport?

Well, there is cave diving and there is cave diving for exploration. So, cave diving is a team sport. Cave diving for exploration, sometimes it has to be a very lonely sport.

What circumstances would lead you to choose to stop cave diving?

I made a decision long ago regarding my tech diving and cave diving. Each year, I aim to either learn something new or refresh my existing skills through a course, and also teach someone else. This constant learning keeps my skills sharp and evolving. If I ever decide to stop training, that’s when I’ll stop cave diving. It would mean I no longer feel safe.

That’s intriguing. When it comes to safety, what percentage of a cave diver’s annual diving activities do you believe should involve cave diving?

I’d recommend a cave dive at least once a month to maintain your skills. Beyond a month, your skills might start to decline. Just doing routine [open water] dives, even if it’s once or twice a month, won’t keep your skills sharp. You need to challenge yourself every few months, doing things your body and mind might have forgotten. That’s why I prioritize taking courses; it keeps my skills at their peak. If you’re not an instructor, find ways to hone your skills. It’s not about how often you dive, but what you do during those dives. For example, if you’re planning a 10-day cave diving expedition after six months of no diving, at least one of those days should focus on reacquainting yourself with cave diving techniques.

Refreshing indeed. It’s been a pleasure. As we wrap up, let’s look ahead. What’s next for you, Carolin, and your team from Underwonder? What future projects are on the horizon, and what can we expect from you in the near future?

Right now, my focus is on continuing my training with various equipment and exploring different environments. Over the last couple of years, I’ve been cave diving in various locations worldwide. Furthermore, I’m training with new rebreathers and other equipment suitable for various environments. It’s essential to have the right tools for each task. I want to travel more, explore different types of caves, and train alongside experienced cave divers and instructors. It’s all about broadening my horizons and gaining more experience. In terms of cinematography, I’m collaborating with many talented individuals I’ve met through the documentary on various projects, such as music videos or short films. It’s an exciting and creative new realm for me, and I’m eager to see where it leads.

Don’t forget to catch the documentary Underwonder to dive deeper into the captivating underwater world of Greek Caves. Follow the links below:

Underwonder Links

Underwonder social media:

https://www.facebook.com/underwonderdoc

https://www.instagram.com/underwonder_doc

https://www.tiktok.com/@underwonder_doc

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Cave Diving, Everything You Always Wanted To Know by Stratis Kas

InDEPTH: It’s About Time—The Advantages of Rebreathers in Caves by Stratis Kas

InDEPTH: The What, Which, and Why of Sidemount by Stratis Kas

Carolin Negrin is a highly skilled Tech, Cave, and CCR Instructor, as well as an underwater Photographer and Cinematographer. As a PSAI (Professional Scuba Association International) Instructor from 2021, she specializes in advanced diving techniques like CCR and deco diving; she also teaches courses such as Advanced Nitrox and Technical Sidemount. Carolin is also certified by RAID (Rebreather Association of International Divers) as a Full Cave and Deco 40 Instructor. Additionally, Carolin is a PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) instructor, teaching a range of diving specialties including CCR diving, deep diving, and underwater photography. Her first documentary, Underwonder, showcases her expertise in underwater cinematography and exploration of underwater caves.

Stratis Kas, a Greek-Italian professional diving instructor, photographer, film director, and author, has spent over a decade as an esteemed Advanced Cave instructor, leading expeditions to extreme locations worldwide. His impressive diving achievements have solidified his expertise in the field. In 2020, Kas published the influential book “Close Calls,” followed by his highly acclaimed second book, “CAVE DIVING: Everything You Always Wanted to Know,” released in 2023. Accessible on stratiskas.com, this comprehensive guide has become a go-to resource for cave diving enthusiasts. Kas’s directorial ventures include the documentary “Amphitrite” (2017), shortlisted for the “Short to the Point” Film Festival, and “Infinite Liquid” (2019), which explores Greece’s uncharted cave diving destinations and was selected for presentation at Tekdive USA. Kas’s expertise has led to invitations as a speaker at prestigious conferences, including Eurotek UK, Tekdive Europe and USA, Tec Expo, and Euditek. For more information about his work and publications, visit stratiskas.com.