Latest Features

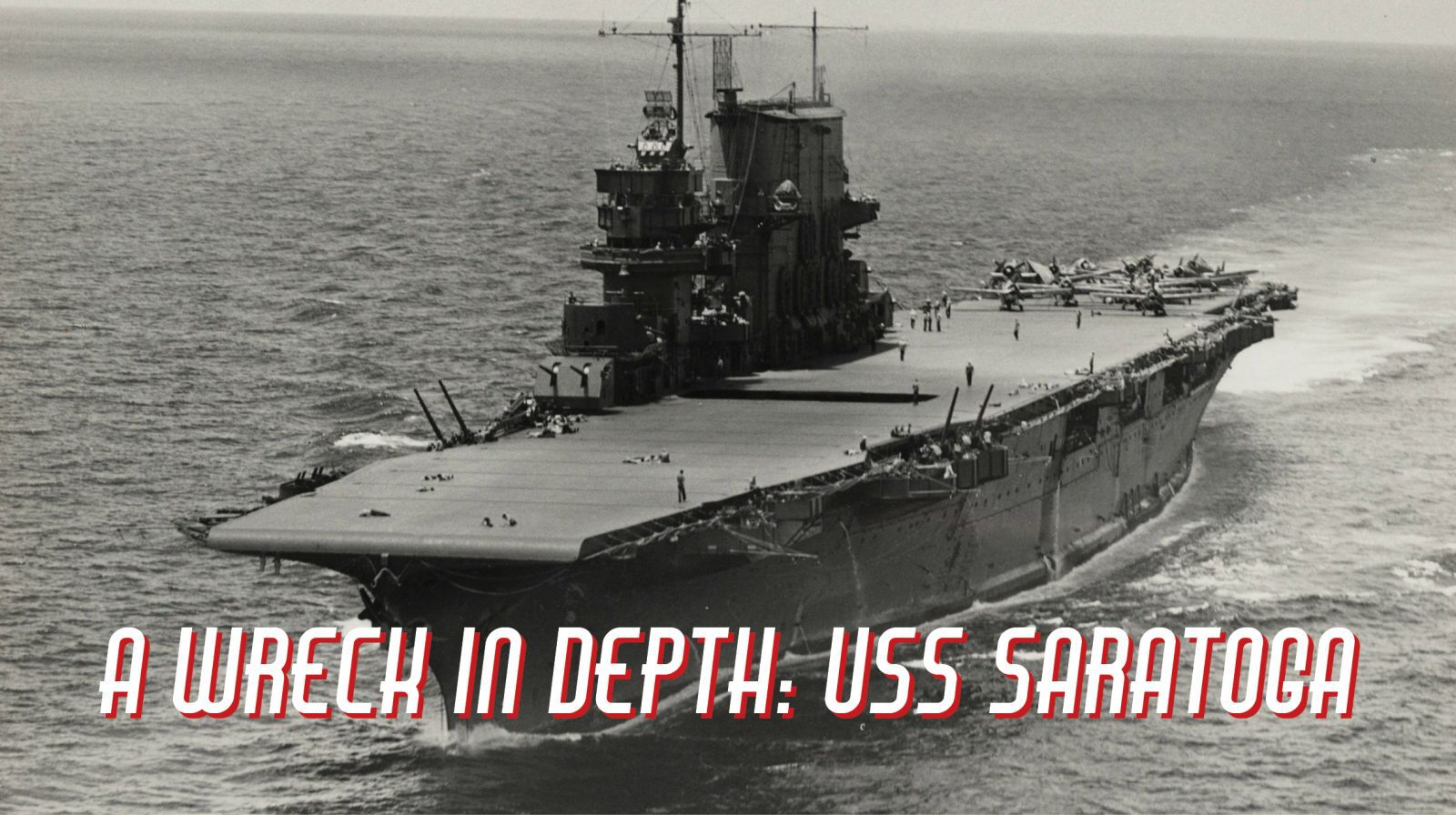

Wreck in Depth: USS Saratoga (CV-3)

The third installment of our historical wreck series brought to you by shipwreck diving travel specialists at Dirty Dozen Expeditions. Are you ready to make the jump?

By Martin Cridge

Header image courtesy of US Navy

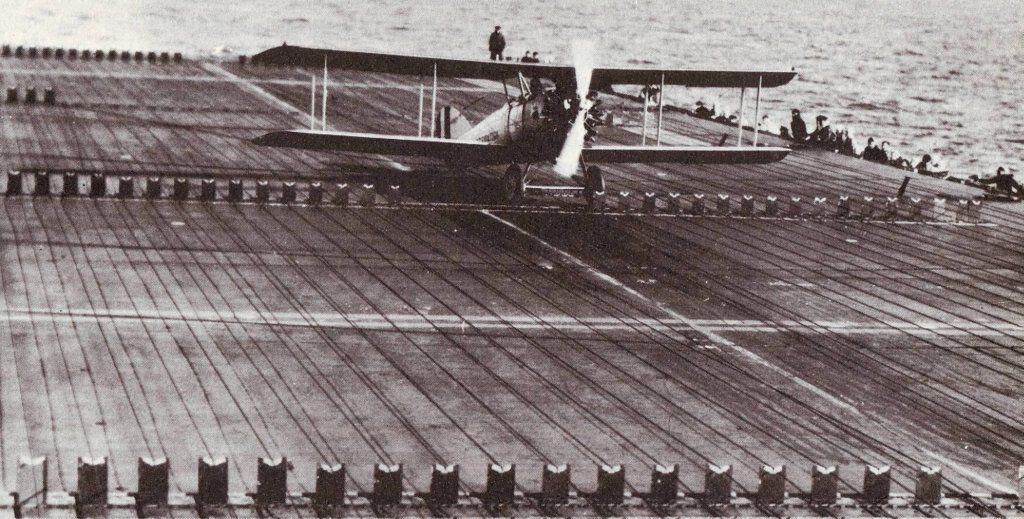

Marc Mitscher pulled the control stick of his aircraft to the side, bringing his plane around and lining up for the first ever aircraft landing on the USS Saratoga (CV-3). Stretched out below him was the 264 m/866 ft flight deck of the newly commissioned carrier.

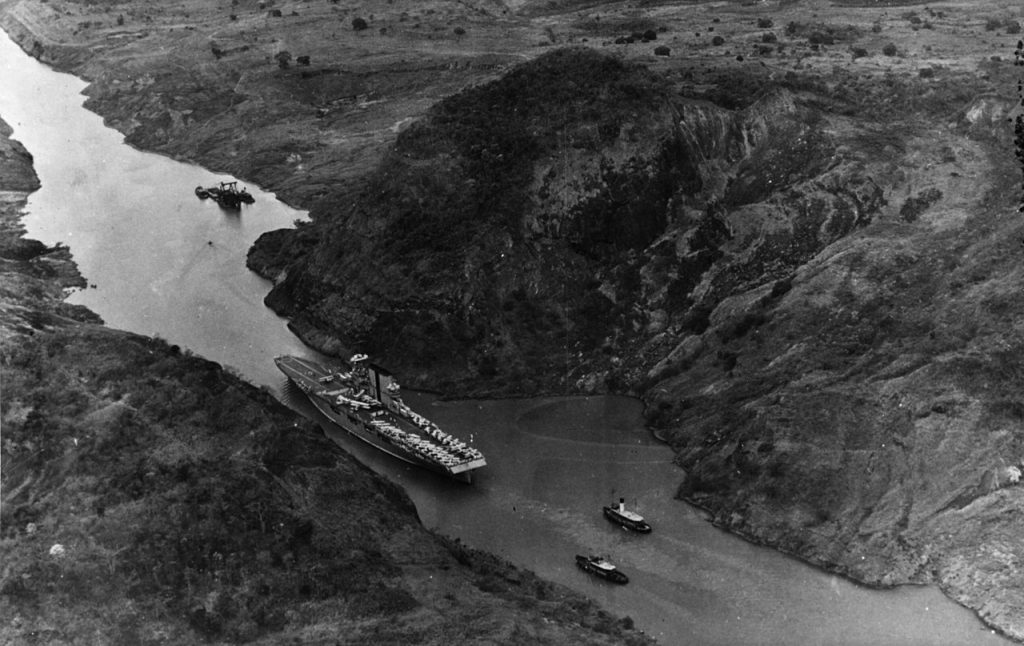

Mitscher would go on to lead the U.S. Fast Carrier Task Force during World War II on a number of daring missions including Operation Hailstone, the fast carrier attack on Truk Lagoon in February 1944. But in January 1928, he was concentrating on bringing his aircraft safely down onto the flight deck of Saratoga. After his successful landing, the rest of his air group followed, and Saratoga went on to conduct her first shakedown cruise before heading to the Pacific via the Panama Canal. Although she was originally designed to pass through the canal, Saratoga knocked down a number of lamp posts on her way through the locks due to the large overhang of her flight deck.

Saratoga would spend the rest of her career assigned to the Pacific Fleet, although she would occasionally take part in exercises or fleet reviews on the east coast during the interwar years.

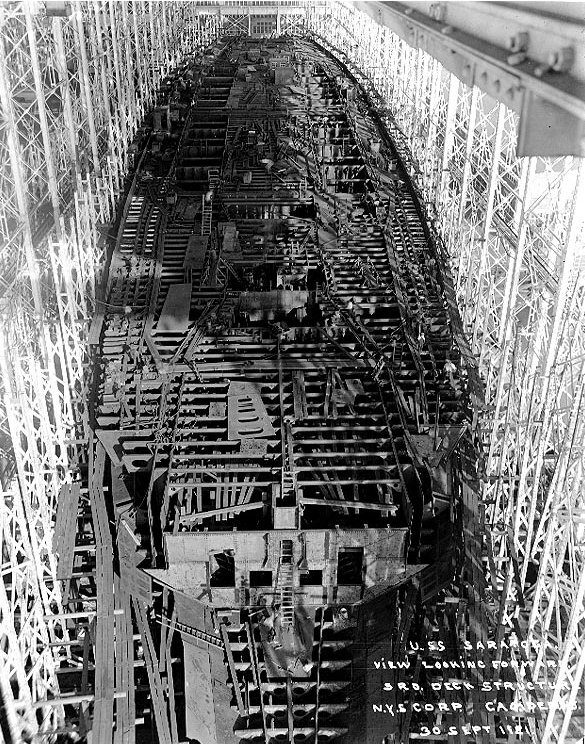

Saratoga was laid down at the Camden, New Jersey yard of the New York Shipbuilding Corporation in September 1920, originally as a Lexington class battlecruiser. In February 1922, the Allies adopted the Washington Naval Treaty, which aimed to prevent a post-World War I arms race. The treaty placed restrictions on the number, size, and armament of certain naval vessels as well as which types of new vessels could be built. As a result of the treaty’s restrictions, the Navy scrapped their plans to build six Lexington class battlecruisers. Part of the treaty, however, allowed two vessels that were already under construction to be converted into aircraft carriers.

So, on July 1, 1922, the Navy selected Saratoga and her sister Lexington to become the fleet’s first aircraft carriers. Japan followed suit and converted the battlecruiser Akagi and the battleship Kaga into aircraft carriers. Aircraft carriers weren’t exempt from the Washington Naval Treaty’s limits on the size and armaments of naval ships. Per the treaty, the vessels were limited to 36,000 tons maximum standard displacement, which included 3,000 tons for antiaircraft and torpedo defenses. This benchmark proved difficult to achieve, and both the Saratoga and Lexington exceeded their limit while the treaty was in force.

Saratoga became the Navy’s first purpose-built fleet carrier to be launched when she glided down the slipway into the Delaware river on April 7, 1925. She was commissioned for the first time at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on November 16, 1927, and sailed for the first time under the command of Captain Harry E. Yarnell. While the original role of aircraft carriers was perceived to be fleet reconnaissance, anti-submarine patrol, and spotting for the big guns of capital ships, the Navy spent the interwar period developing tactics and multi-mission capabilities of aircraft carriers through a number of fleet training exercises and war games.

Naval Aviation grew to become a key component of fleet battle tactics and was constantly developed to improve and project the fleet’s strike power over the horizon. Other scenarios were played out in exercises that developed the Navy’s ability to attack other aircraft carriers and shore bases, as well as to offer support for amphibious operations. In one fleet problem exercise in 1938, Saratoga successfully launched a surprise air attack on Hawaii in what was an almost identical scenario to the Japanese attack in December 1941.

The Aftermath of Pearl Harbor

At the start of the Pacific war, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Saratoga was in San Diego, having just completed a dry dock and maintenance period. After embarking her air group, she managed to get underway within 24 hours of the Japanese attack for her first mission of the war—carrying reinforcements for the U.S. garrison on Wake Island. Ultimately, the mission was cancelled before Saratoga could reach Wake, and the island fell into Japanese hands.

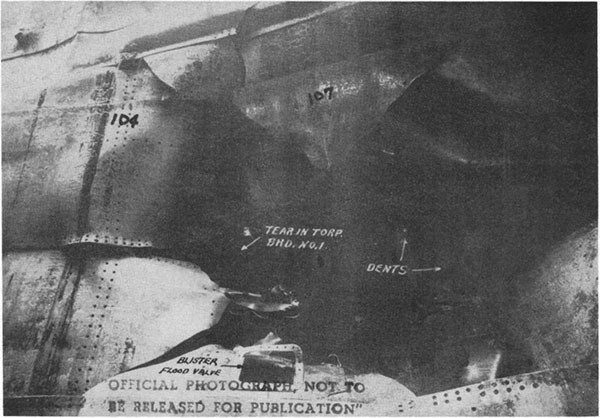

In January 1942, the Japanese submarine I-6 torpedoed Saratoga for the first time, forcing her to return to the west coast for repairs. Returning to the fleet just before the Battle of Midway, the fighting was finished by the time she reached Pearl Harbor where she loaded replacement aircraft for both the Hornet and Enterprise so that they could replace the planes they lost in the battle.

By August 7, 1942, Saratoga was in the Solomon Islands supporting the U.S. offensive on Guadalcanal. At the end of August, Saratoga was torpedoed for a second time, this time by submarine I-26. After repairs at Pearl Harbor, Saratoga returned to the South Pacific.

Saratoga spent most of 1943 operating from Nouméa in New Caledonia supporting operations in and around the Solomons. She was, for a while, the only operational U.S. carrier in the Pacific. In November, Saratoga supported the U.S. offensive in the Gilbert Islands and Nauru before heading back to the west coast for a much needed refit.

January 1944 saw Saratoga back in action, this time supporting operations in the Marshall Islands before joining the British Eastern Fleet, which was operating in the Indian Ocean. During operations with the British, Saratoga carried out a number of successful raids on both Sumatra and Java during April and May.

In June that year, the Saratoga was back in dry dock at the Bremerton yard in Washington, and when she emerged in September, she had a new, special role. Saratoga was chosen to develop night fighting tactics and to train pilots for night fighter operations.

In 1945, Saratoga returned to frontline duty, and in February was tasked to provide air cover for the amphibious landings on Iwo Jima. On February 21, she was hit by kamikaze planes and bombs in two separate attacks by the Japanese. Although the forward part of her flight deck was seriously damaged, she managed to recover her aircraft before retiring from the operation and returning to the U.S. for further repairs.

During the repairs, the Navy decided to convert Saratoga permanently into a training carrier. The aft aircraft elevator was welded in the up position and all its associated machinery was removed. A larger forward elevator was fitted and its operating machinery upgraded. Finally, parts of the hangar deck were converted into accommodations and classrooms. Saratoga spent the remaining months of the war as a training venue for pilots operating out of Pearl Harbor.

Once the Japanese had surrendered, Saratoga took part in Operation Magic Carpet, the repatriation of American servicemen. In the end, she took over 29,000 American servicemen home, more than any other ship. Since Mitscher’s first landing in January 1928, over 98,500 planes had touched down on Saratoga’s flight deck, setting a U.S. Navy record.

As a result of technical advancements made during the war, the Saratoga had become obsolete, and she was selected to take part in Operation Crossroads, the first atomic tests at Bikini. She departed from the U.S. mainland for the last time on May 1, 1946, sailing out under the Golden Gate bridge from San Francisco for her date with destiny at Bikini Atoll.

For test Able, Saratoga was deliberately positioned some distance from the planned zero point so that she could be used later in test Baker. After the Able test she suffered some minor damage, mainly from fires on her teak-covered flight deck, but these were soon extinguished.

Some of her crew even moved back onboard the ship for a couple of weeks while preparations for the Baker test were made. Despite being placed in the expected fatal zone for the Baker blast, some of these crew members left their kits and personal belongings onboard, believing the Saratoga wouldn’t sink.

But she did.

Diving One of the Largest Shipwrecks in the World

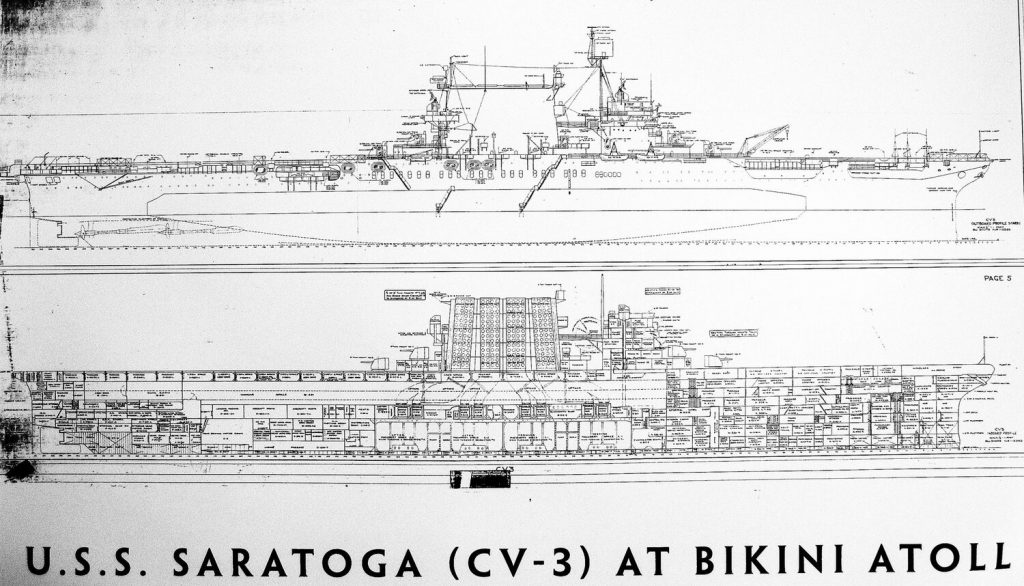

As built, Saratoga‘s official standard displacement was 36,000 tons (43,055 tons full load), and she was 270 m/888 ft long. Modifications to the vessel in 1945 increased her full load displacement to 49,552 tons and her overall length to 277 m/909 ft, making her one of the largest diveable shipwrecks in the world.

The Saratoga now sits upright in 51 m/167 ft of water with the top of her superstructure reaching 18 m/60 ft and the flight deck averaging 27 m/90 ft.

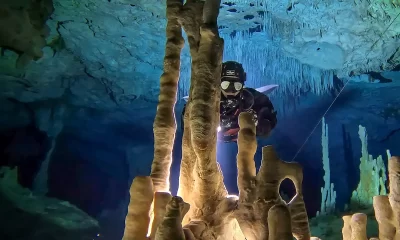

First dives on the Saratoga are truly awe-inspiring. This is a big wreck, and just orienting yourself can take a number of dives.

The effects of two atomic explosions, war damage, and general deterioration from over seventy years of resting on the lagoon bottom are now starting to show, with parts of her superstructure, hull, and flight deck collapsing in recent years. None of this, however, diminishes the impressive nature of this wreck.

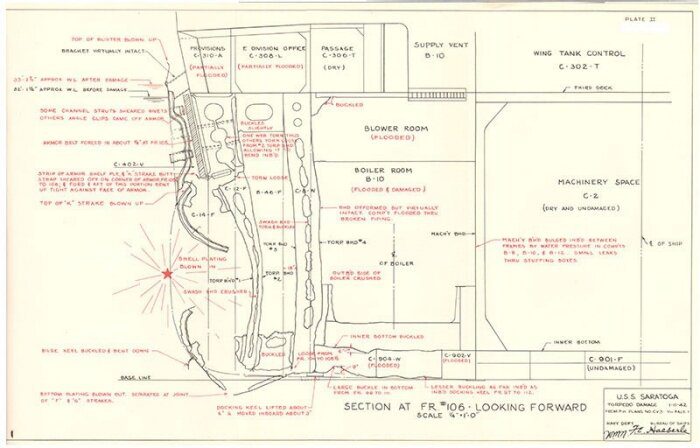

After the Baker bomb exploded underneath LSM-60, the Saratoga was hit by a number of massive tidal waves which lifted the mighty vessel and smashed into her sides, causing serious damage to her side plating. Two million tons of coral, sand, and water were thrown up into the air by the explosion, which then came crashing down onto the flight deck.

Saratoga was built with an unarmored flight deck. This maximized hangar space and was more easily repaired but was obviously not as strong as an armored deck. Although original reports by Navy divers after Saratoga sank said that the flight deck was largely intact, it was seriously dished from the aft elevator to the stern over the hangar deck area. It’s likely that it was seriously damaged and would have been unusable had the ship not sank. Now, large parts have collapsed onto the hangar deck below.

A number of planes and various pieces of military equipment were staged on the flight deck for the Baker test. The planes were all swept off the deck during the test, and the remains of some of them are now scattered around the Saratoga on the seabed, some still in surprisingly good condition. Planes were also stowed on the hangar deck, although these are now mostly inaccessible due to the collapse of the flight deck over the hangar. It’s still possible to see into the cockpits of some of them, but these planes are now, sadly, in poor condition.

Some of Saratoga’s main ship armaments were removed prior to Operation Crossroads, but a representative number were left onboard, including 2x twin 38 caliber 5″ dual purpose gun mounts, a number of single 5″ dual purpose gun mounts on the sponsons down each side of the ship, along with an array of 40mm Bofor and 20mm Oerlikon guns.

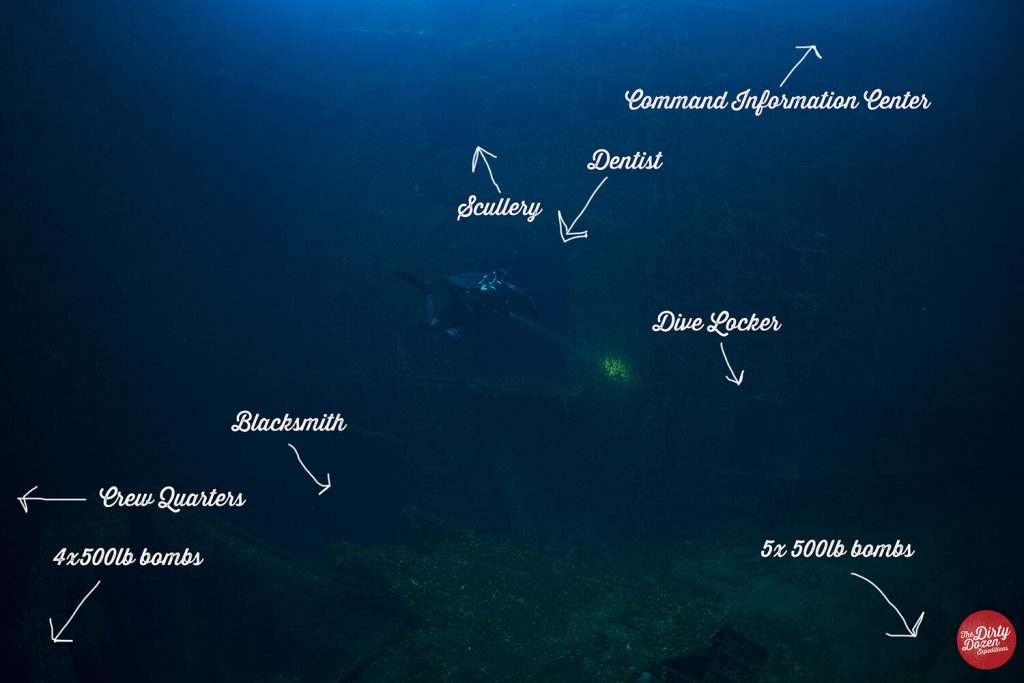

Lots of munitions were also onboard when the Saratoga was sunk. These include 159 kg/350 lb and 227 kg/500 lb bombs, air drop torpedoes, rockets, 5” gun cartridges, and depth charges, all of which can still be found scattered in and around the wreck today.

Forward of the forward aircraft elevator, the flight deck is still largely intact apart from a small area towards the bow. This is one of the areas where Saratoga was hit when she was off Iwo Jima—in February 1945—and was hastily repaired. Now the damaged area allows access to the bow area under the flight deck, including the emergency radio room—with all of its vacuum tubes and dials—and the lamp locker with some lamps still in place.

Inside the Saratoga

The interior of the Saratoga is vast, and probably no more than 10% of the ship has been properly explored since her sinking. The Saratoga was heavily compartmentalized, and the majority of her watertight doors and hatches were closed when she sank, hindering today’s explorations. Most of the penetrations go forward from the forward elevator shaft at various levels.

In some areas, permanent lines have been laid, but care is still needed, as a fine silt is present that is easily stirred up within most parts of the vessel. Needless to say, excellent buoyancy skills are a must to avoid silt outs, and divers need to be constantly aware of their surroundings. Divers with the necessary skills and experience who do venture inside are richly rewarded with a number of unique sights. A maze of passageways lead off in all directions to storerooms, workshops, galleys, pantries, mess decks, accommodation decks, and bathrooms.

You can visit the Command Information Center, the nerve center of the ship when it was operating at war. The cabins and bathrooms used by Admirals and Captains are nearby. Divers can visit the ready room where pilots were briefed on their upcoming missions, and the machine shops packed with lathes, grinding wheels, bench drills, and metal- and wood-working tools. Probably the most impressive area, however—especially for those not suffering from dental-phobia—is the dentist’s surgery and sickbay. Three dentist chairs sit in the surgery, complete with dental drills, instruments, and rinse bowls. Everything is almost perfectly preserved, and if it weren’t for the fine layer of silt covering everything, the room would look like it was just waiting to receive its next patient.

Elsewhere on the ship, countless artifacts lay scattered around, including plates, bowls, jugs, Coca Cola, bottles, and other debris, much of which has laid untouched since 1946. In store rooms, shelves full of spare parts are still crammed with items including gauges, thermometers, valves, and fittings.

Two of the more interesting and unique items for divers to see are the U.S. Navy Mark V diving helmets and standard dress drysuits. The US Navy Mark V diving helmet is one of the most well known diving helmets in the world. First introduced in 1916, it was used until 1984 and can still be purchased new today.

All too soon, however, it is time to head back to the surface. Instead of planes, divers can see reef sharks and eagle rays cruising up and down the flight deck and turtles munching on the coral and algae. Large shoals of jacks, trevally, and rainbow runners will swim around divers as they head back up the mooring line to the surface. While divers complete their deco, they will peer out into the blue to see if the tiger sharks will turn up, and often they do. If they are really lucky, some mantas may cruise by, or even the odd whale shark or tiger shark.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: A Wreck In Depth: The IJN Nagato, Bikini Atoll by Martin Cridge

InDEPTH: Wreck In Depth: Prinz Eugen by Martin Cridge

InDEPTH: In Memoriam: Martin Cridge by Aron Arngrimsson and Steve Jones

Capt. Martin Cridge—Without Martin The Dirty Dozen Expeditions wouldn’t exist. A few years back, Aron and Martin spent a full year diving together in Truk Lagoon. One evening, after a day of demanding dives, they sat, had a beer, and came up with their ideal CCR wreck dive itinerary.

The first ever Dirty Dozen trip was the result of that beer and the rest is history. Martin has lived in Truk for eight years with his family and works as the skipper of our expedition vessel in Truk and Bikini.