DCS

What is Undeserved in “Undeserved Decompression Sickness?”

Divers still seek comfort in the notion of the “underserved” hit to explain unexpected incidents of decompression sickness. “Hey, my computer said I was fine.” NOT. Here diving physiologist Dr. Neal Pollock exposes the fault in this notion. While decompression algorithms take into account the divers’ profiles, i.e., time and pressure, there are many factors that can potentially impact divers’ decompressions, as the author explains. Once divers’ reject the escapism that accompanies the ‘undeserved’ label, they can get on with the important business of diving and giving adequate consideration in their deco planning.

by Neal W. Pollock, PhD

Spoiler Alert: the most undeserved element in the title is the word “undeserved.”

Describing cases of decompression sickness as “undeserved” generally speaks more from an emotional perspective than a rational one. The driving factors are typically faith in imperfect tools and a desire (conscious or unconscious) to shift responsibility.

Decompression algorithms rely almost exclusively on pressure and time data to predict effects. Enticing pictures can be painted on the authority of any algorithm, but the reality is that all rely on limited input to interpret complex situations for people who are not uniform. Modern decompression models are important constructs that can help us to dive safely, but the products are rudimentary from a physiological perspective, without sufficient sophistication to deserve unquestioned trust.

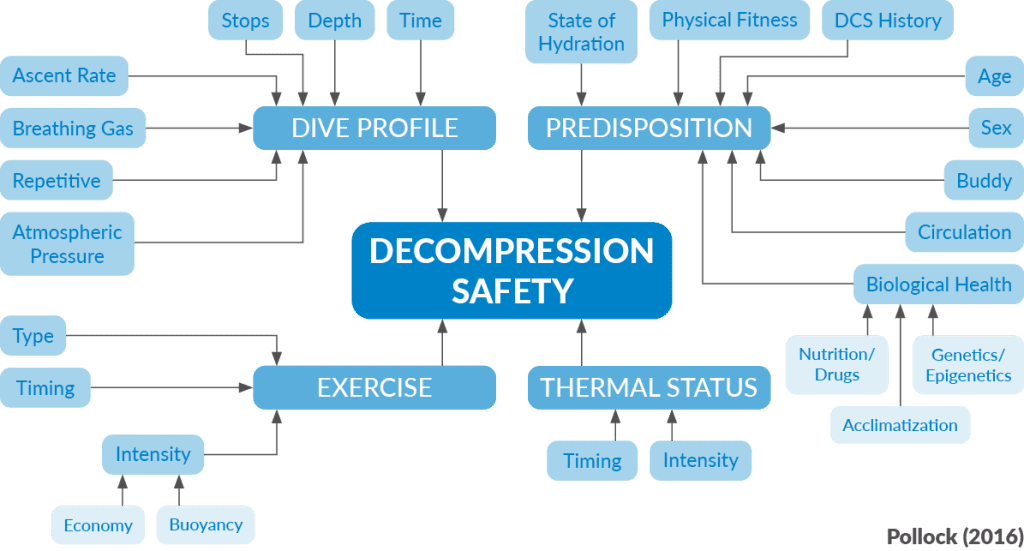

The dive profile is almost certainly the most important determinant of gas uptake and elimination, but the truth is that we do not yet have sufficient data to quantify the impact of many of the variables that can influence outcomes (Pollock 2016). Instead, algorithms rely on simple measures and mathematical bracketing with the hope of covering the contributing factors. The problem is not in doing this; the problem is in being surprised when the outcome is not what was expected.

Decompression Factors

Accepting that the dive profile is the most important determinant of decompression risk, there are additional factors that can also have dramatic effects. Exercise is one of these. Pre-dive exercise may have complicated effects on the subsequent diving exposure. Exercise during the descent and bottom phase will increase inert gas uptake and the resulting decompression stress. Mild exercise during the ascent and stop phase can promote inert gas elimination and decrease the resulting decompression stress, but excessive exercise can promote bubble formation and increase decompression stress. Post-dive exercise is likely to increase decompression stress in all cases. Practically, while the concepts are clear, the definition of meaningful thresholds for “mild” and “excessive” exercise is difficult at best, and quantifying real-time effects far exceeds current capabilities.

Thermal state is another potentially dramatic factor (Gerth et al. 2007). Being warm during the descent and bottom phase can substantially increase blood flow and delivery of inert gas to the periphery and increase the subsequent decompression stress. Being cool during the descent and bottom phase can decrease inert gas uptake and decrease the subsequent decompression stress. Being cool during the ascent and stop phase will inhibit inert gas elimination and increase the subsequent decompression stress. Being moderately warm during the ascent and stop phase can promote blood circulation to the periphery and increase inert gas elimination, but excessive heating of peripheral tissues in this same phase can promote bubble formation as heating decreases the solubility of inert gas, effectively increasing the decompression stress.

Again, as with exercise, it is extremely difficult to identify meaningful thresholds for thermal state at different points in a dive, and quantifying real-time effects is not within current capabilities. It is certainly clear that the ambient temperature measured by a dive computer can have little correlation to the thermal status of the diver, and any thought that this information informs decompression models in a meaningful way is misplaced.

The wild card of individual (“predisposition”) factors further highlights the challenges unmet in current decompression models. Not only are these parameters not measured, it is unclear how the information could practically guide the risk assessment at this time if available. While the importance of these factors is hard to assess, it is also noteworthy that some, most often dehydration, may be used as scapegoats to explain away decompression sickness (DCS).

A state of dehydration can adversely affect circulation, potentially impeding inert gas elimination, but this almost certainly has much less impact than the dive profile, exercise, or thermal state in many cases. The impact is also not as straightforward as making it a blame agent might imply. For example, if a state of dehydration impairs inert gas elimination during the ascent and stop phase to increase decompression stress, might it not also decrease inert gas uptake during the descent and bottom phase to reduce the decompression stress?

Sound levels of hydration are good for general health and probably for decompression safety, but a state of dehydration in no way guarantees an outcome of DCS, just like a good level of hydration in no way guarantees an outcome of no DCS. The blame directed to dehydration is probably related to the observation that DCS can be accompanied by clinically important fluid shifts. This, though, is more a consequence of the disease than a cause.

The rest of the predisposition factors offer similar challenges. Physical fitness appears to confer some protection against decompression stress, but the quantification of such effects is not yet possible. A history of DCS can go either way, with persons prioritizing blame shifting over understanding or behavioral changes having a higher risk of repeat events, and persons improving understanding and moderating risk factors having a lower risk of repeat events. Increasing age is a risk factor, but the partitioning of chronological vs physiological age still needs to be worked out, as does the interaction between age, physical fitness, and biological health.

Women might have a slightly higher physiological risk, particularly during the first half of their menstrual cycle, but this is likely largely (or more than) mitigated by sex-based differences in risk tolerance and practices. The norms and practices of a buddy can affect individual risk either positively or negatively. Circulation issues include state of hydration, the presence of a patent foramen ovale (PFO), and possibly old injury sites that disrupt circulatory pathways. The presence of a PFO is likely only able to become important in decompression stress if bubbles are present, which will depend on a host of other factors. Biological health elements are likely to offer interesting insights in the future, but the ability to assess and understand them exceeds current capabilities.

The major point here is that there are a lot of unknowns and half-knowns that make it important to not expect any decompression algorithm to describe truth. They offer a first order approximation of risk. They provide what might be reasonable guidance within a wide swath of possible error. Staying within guidelines does not guarantee safety. The goal should be to plan for the possibility of suboptimal elements, perhaps several of them, that could influence outcomes.

Conservative Settings

Divers often address the recognized shortcomings of dive-computer-based decompression models by altering conservative settings and/or practice. Those who feel they are bends-resistant may push the limits; those who prefer greater peace of mind may add buffers. One of the additional challenges is that not all practices put forward to enhance conservatism will actually act in that way. The best example of this is probably deep stops. The concept of stopping deep to minimize bubble formation was enticing, but flawed. Stopping too deep will certainly minimize the possibility of bubble formation at that point, but at a point when it would never reasonably be expected for bubble formation to occur. The problem is that the time at the deep stop depth allows any tissue that is not fully saturated to take up more inert gas. The additional uptake creates increased decompression stress as the diver ascends. The concept was well intended, but the impact was counterproductive.

One of the conservative settings that is intuitively simple is gradient factors. The M-value describes a theoretical limit of supersaturation that a tissue can tolerate before problematic levels of decompression stress develop. This limit is another first order approximation of risk, with no guarantees of safety if staying within the limit. Gradient factors (GF) simply tailor limits to a different percentage of the M-value. GFs are typically presented as two values, GFlow and GFhigh, presented as GFlow/GFhigh. Those who believe in deep stops may choose a GFlow less than or equal to 20%. Those who do not believe in deep stops will likely choose a GFlow equal to or greater than 30%. Those who feel confident in their overall ability to tolerate decompression stress might choose a GFhigh in the 85% range. Those who want to add more buffers to protect against unknowns and surprises might choose a GFhigh less than or equal to 70%.

Determining whether a case of DCS should be considered “deserved” or “undeserved” is problematic when prescribed limits are based on incomplete data and when they can be altered by a variety of settings. The argument, “My computer said it was okay!” holds little if any weight. A better approach is to focus on the fundamentals. The first fundamental is to consider when DCS is a possibility. As a rough rule of thumb, any dive within the traditional recreational range (40 m/132 ft) that is approaching half the US Navy no-decompression limit carries a non-zero risk of DCS. Similarly, pretty much any dive deeper than the traditional range carries a non-zero risk. “Non-zero risk” repudiates the claim of “undeserved.”

Once the possibility of DCS has been accepted, the most productive deliberation includes an honest assessment of all of the risk factors that may have contributed to the outcome. While trying to pin the blame on one modifiable risk factor can be comforting, it probably does much less to ensure future safety. There are many effects that cannot yet be quantified, but the risk potential can be recognized. Focusing on any one variable can discourage a more honest appraisal of the possibilities.

Assessing the Risk

DCS symptoms may develop due to frank violations of accepted practice, but many cases are shrouded in ambiguity. An honest and objective assessment will almost certainly improve understanding and future outcomes more than claiming an “undeserved hit” will. It is unlikely that any two exposures will truly be identical, either for two divers sharing one dive or one diver repeating a given dive. Subtle differences can accumulate to have a meaningful impact. These differences coexist with the probabilistic nature of decompression stress, effectively that a safe outcome experienced once or several times may not guarantee the same for all future exposures.

Once all reasonable contributing factors have been considered, some room should be left for doubt. Appreciating the knowns, the unknowns, and the complexity of interactions can promote thoughtful practice without frustration. Practices can be optimized without guarantees. The first step is getting rid of the escapism that accompanies the “undeserved” label.

DIVE DEEPER

Gerth WA, Ruterbusch VL, Long ET. The influence of thermal exposure on diver susceptibility to decompression sickness. NEDU Report TR 06-07. November, 2007; 70 pp.

Pollock NW. Factors in decompression stress. In: Pollock NW, Sellers SH, Godfrey JM, eds. Rebreathers and Scientific Diving. Proceedings of NPS/NOAA/DAN/AAUS Workshop. Wrigley Marine Science Center, Catalina Island, CA; 2016; 145-56.

InDEPTH: In Hot Water: Do Active Heating Systems Increase The Risk of DCI? by Reilly Fogarty

Neal Pollock holds a Research Chair in Hyperbaric and Diving Medicine and is an Associate Professor in Kinesiology at Université Laval in Québec, Canada. He was previously Research Director at Divers Alert Network (DAN) in Durham, North Carolina. His academic training is in zoology, exercise physiology, and environmental physiology. His research interests focus on human health and safety in extreme environments.