Cave

Tom Mount (1939-2022) Brought Considerable Depth and Experience to Technical Diving

Though most tech divers have heard of Tom Mount and the International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD), it’s likely only a few insiders know his back story and about the considerable depth and experience he brought to what would become known as technical diving. Here author and Asian tech pioneer, Simon Pridmore takes us on a deep dive into Mount’s many achievements. May he rest in peace.

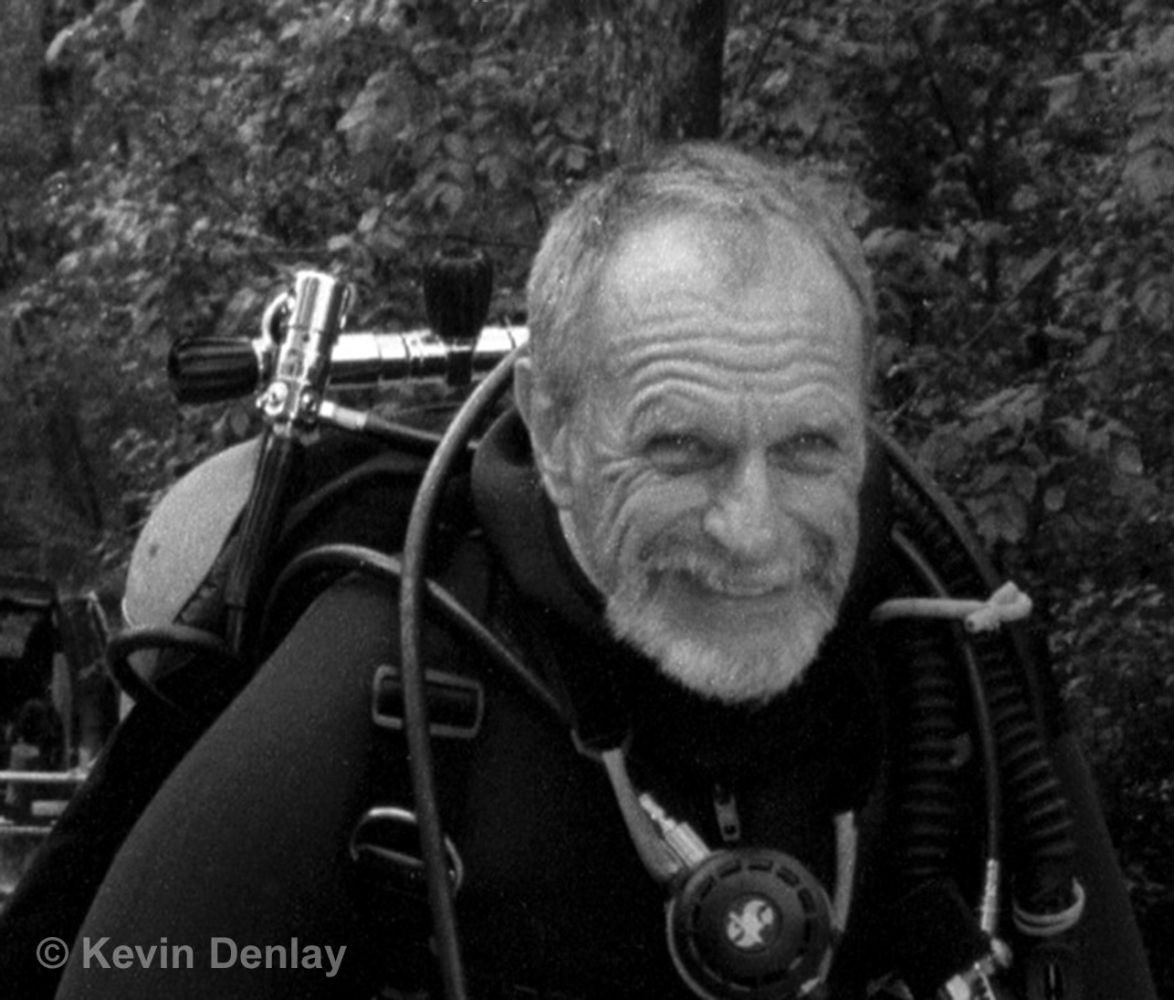

By Simon Pridmore. Header image, “The old warhorse —Tom Mount post-dive 1993 Ginnie Springs. Photo by Kevin Denlay

In January, when the news emerged of Tom Mount’s death, Facebook lit up with hundreds of messages from right across the acquaintance spectrum. Some were from close friends who had known Tom for many years; others were from people he had only met briefly or quite recently. Some comments even began with the words, “Although I never got to meet Tom…” and then went on to express their sadness at his passing.

Condolences poured in from all over the world, not only from Florida and elsewhere in the USA, but also from Central America, the UK, Europe, Southeast Asia, China, Australia, New Zealand, Micronesia, pretty much everywhere people scuba dive. Many were from countries Tom never visited, written in languages he didn’t speak.

He was 82 when he died. If in 1989, you told the then 50-year-old Tom Mount that his death would send a minor tremor right around the diving world, he would have been astonished. Up to that point, he had achieved a great deal, but he was little known outside America. Within a few years, his fame would be global.

How did this happen?

As is often the case, to understand why the path winds the way it does, you have to go back and follow it from the start.

Beginnings

Tom was born Warren Thomas Mount in 1939. He learned to box when he was nine years old and thus began a lifelong passion for martial arts, which would both keep him fit into his older years and provide much of the philosophy behind his approach to scuba diving.

The US Navy taught him to dive. He joined up in 1957 and became a Navy diver. He was also attached for a time to the Army Corps of Engineers and was primary author of the Army Corps of Engineers (Diving) Course Syllabus.

Rebreathers

The Navy used both open circuit and closed circuit apparatus. Navy divers were introduced to the aqualung by its co-creator Emile Gagnan in early 1949 and, during Tom’s time, the rebreather units they deployed included the Draeger LT Lund II and the Emerson – Lambertsen UBA.

In the 1990s and beyond, Tom would subsequently become a passionate advocate for the use of rebreathers in sport diving. Inventors and manufacturers would beat a path to his door, seeking his advice. Dive Rite’s Lamar Hires was one of the beneficiaries.

“We visited him in Miami and Jared and I went out on his boat. Tom and I took two units down to about 18m/60 f and tested them. I was new to rebreathers and needed his guidance on the design. He was very impressed with it but, more importantly, I got a one-on-one lesson about loop volume and trim. I remember watching Tom pull off weight because he was heavy and I proceeded to do the same thing. The discussions that followed helped shape the product.”

Mixed Gas

After leaving the Navy, Tom went to work as diving officer for Lockheed at Cape Kennedy (Canaveral), the base for NASA’s space program.

In 1967, he took up a position as director of the Scientific Diving Program (SDP) at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (RSMAS). The school’s website recounts how, under Tom’s direction:

“The SDP introduced mixed gas diving to RSMAS scientists.”

He ran the program from 1968 to 1976, when he left to spend two years with the YMCA as its national scuba programme training director.

During this time, however, Tom often had matters other than work on his mind.

Going Underground

Just before leaving the Navy, he discovered cave diving. His first introduction was at Zuber Sink, northwest of Ocala, Florida, later to be acquired by Hal Watts and renamed as Hal’s Forty Fathom Grotto. Watts and Tom first met around this time and were to stay firm friends to the end.

Tom referred to these early days in a 1995 aquaCORPS magazine interview.

“I started deep diving when I got out of the Navy in 1962 and I thought I was a real pioneer. I was shocked to find that people were (already) getting into the Andrea Doria and working at 250, 260 feet in caves.”

By 1963, both Watts and Tom were training cave divers and doing deep cave dives. Tom teamed up with Frank Martz to bottom out Zuber Sink at 240ft (hence “Forty Fathom”) and explore the hitherto unvisited depths of Lost Sink, later to become better known as Eagle’s Nest. In 1965, Tom and Martz set the world record for the deepest scuba dive on air with a descent to 110 m/360 ft, a record that stood until Watts and A.J. Muns dived to 120 m/390 ft two years later.

They were at the pinnacle of their sport. In 1966, Sheck Exley, a man who was later to become one of the deep cave diving elite himself, did his first cave dive. Writing in 1984 and harking back to his very early days, Exley wrote:

“Now, for better or for worse, my life was set. Sports heroes…were now replaced by Mount, Watts, Harper on the list of people I most admired. Hal Watts was the best deep cave diver, Tom Mount had the most cave dives and was the best published and John Harper was simply the best, period.”

Premonition

In the late 1960s, Lithuanian Dr. George Benjamin became fascinated by the Blue Holes of Andros in the Bahamas and started diving in them. Long on enthusiasm but short on experience, as he began to explore deeper, Benjamin decided he needed help and invited Tom to come over from Florida to join him. Tom recruited other top Florida cave divers to form a team to push the cave system deeper and further. These included Martz, Tom’s then wife Zidi Goldstein, Ike Ikehara, Jim Lockwood, Sharee Pepper, and Dick Williams.

In early 1971, Tom and Martz found a new tunnel with a restriction at 85 m/280 t. When the team returned in September of the same year, Martz was determined to try to go beyond the restriction. Benjamin was against the idea. He thought it was dangerous and conflicted with his plans. And he was paying the bills. Tom told Martz that the project was their priority, but Martz was insistent and eventually Tom persuaded Benjamin to allow the dive to go ahead.

It was a story Tom would often tell.

“Frank died on a dive in Benjamin’s Cave in Andros Blue Hole 4 in the Bahamas on September 4, 1971. Frank and Jim Lockwood were going to explore a passage Frank had found on our last trip there. Zidi and I were to add line in the other passage. Prior to the dive I had a premonition one of us would have an accident. Normally I listen to my intuition, but on this dive I did not. Frank and I had argued earlier…so I thought my bad feeling was over our disagreement.

But I did continue to have the feeling as the dive started. About 25 minutes into the dive, I felt someone had died. It was not Zidi or me, and as we exited we saw Jim. Jim and Frank had got into a bad silt out and Jim felt Frank had passed him, so expected to see him on the way out. Zidi went up to decompress and Jim and I doubled back to try and find Frank. We pushed our air to the maximum and returned to decompress on oxygen.”

To this day, Martz’s body has not been found.

The subsequent police investigation report quotes Tom as saying:

“Frank Martz was probably one of the best cave divers in the world…He was one of my best friends and one of the people you think it is impossible for them to die diving. He has done more to develop safe cave diving equipment than anyone and the cave diving world will miss him…”

Tom always cited Martz’s death as a turning point. You can just feel his disbelief in his police statement. Subsequently, he and others came up with a variety of wild theories to explain how Frank had died. The possibility that he had just got something wrong was too hard to process.

Like other technical diving pioneers, the experience of losing a close friend to the sport would act as a driving force.

In his book, Technical Diving from the Bottom Up, Kevin Gurr recalls:

“In the water, (Tom) was, and still is, a task master. I’d never heard anyone scream underwater before. You knew when you’d screwed up.”

That was Tom’s style. He could be absolutely terrifying; chewing you out in the darkness, half a mile into a cave, when you made a mistake. But behind the unintelligible bellowing was the message:

“My best friend, the best cave diver I knew, made a mistake and died in a cave. If it happened to him, it can happen to you and it will happen to you if you don’t focus constantly. Never again! Not on my watch!”

Education

A few years earlier, together with Watts and others, Tom had already been involved in measures to improve safety standards in cave diving. The increasing interest and participation in the sport in the 1960s had led to a number of diver deaths, which in turn led to bad press and political pressure on land owners to close off access to the caves; even threats to ban cave diving altogether.

In response, the USA’s first cave diving organization, The National Association of Cave Divers (NACD) was established to offer courses and certification in cavern and cave diving with the goal of improving safety. Those who assembled in Gainesville, Florida, on May 21, 1969, to sign the articles of incorporation were Tom Mount, Hal Watts, Dale Malloy, David Desautels, Lawrence Briel, Ronald Wahl, James Sweeney, and Gilbert Milner.

Tom was NACD training director and, after Martz’s death, wrote The Cave Diving Manual (1972), one of the first US cave diver textbooks (the very first was Exley’s Dixie Cavern Kings Cave Diving Manual (1969). Subsequently, Tom was lead author on Safe Cave Diving (1973), to which Exley also contributed.

In terms of his speaking voice, Tom was far from a perfect communicator, especially if you were not a native English speaker, his drawl and soft speaking voice making it difficult to pick up what he was saying.

Fortunately, over the years, he wrote it all down. The cave manuals were followed by Practical Diving: A Complete Manual for Compressed Air Divers (1975), written with Ikehara and published by the University of Miami.

Many more books would follow.

Survival

Survival was a common theme in his teaching and writing. He would frequently tell the story of an air sharing exit when he and a fellow diver both ran out of air a long way before the end of the cave, yet kept pushing on, finning regularly, not panicking, knowing that it was the only way they could survive. Two mantras that his students would hear time and again were:

“Only you can breathe for you, only you can swim for you, only you can think for you”

“Survival is making the choice to continue and not quitting regardless of the odds.”

One DEMA Show, Tom was receiving an award in front of a large crowd and, in the front row, he spotted Don Shirley, one of South Africa’s top cave divers. Calling him up on stage, Tom told the story of how Shirley had survived an eight-hour ascent from a deep cave while suffering from devastating, crippling decompression sickness. Pointing to Shirley, Tom announced:

“This is the guy who deserves an award. He is a true hero. He survived when it would have been easier not to.”

Mindfulness

Mindfulness, a concept borrowed from his martial arts training and his PhD studies, was another standout feature of Tom’s training technique. In his description of the circumstances leading up to Martz’s death (above), he talks about premonition and intuition. Tom saw developing awareness of these phenomena, and listening to your feelings as important components of a survival mentality. The course materials he developed also included advice for divers of the value of pre-dive visualisation and post-dive reflection.

Nowadays, technical diver training has come to accommodate all these aspects, but when Tom first introduced them they were radical and innovative. Divers being divers, they generated a certain amount of cynicism and Tom was dubbed Obi-Wan Kenobi (although not within earshot). During a course, divers would dread the meditation session at the end of a long day of caves and classes. The urge to fall asleep was almost impossible to resist. Nobody wanted to be the first to shatter the peace with a loud snore!

Tom saw introducing mindfulness to extreme scuba divers as one of the most significant elements of his legacy. In his TekDive USA 2016 speaker biography he wrote:

“…our primary strengths lie in the ability to use intuition and our use of Chi. (I consider) three elements of Survival and Existence to be the key to life.”

Turning Point

During the 1980s, Tom wrote travel guides, took underwater photographs, and submitted articles for dive magazines. Together with Patti Schaeffer, who was to become his wife and business partner for the next two decades, he even published A Guide to Underwater Modeling (1983).

Tom’s author biography in this book gives a good idea of the scope of what he was doing around this period. He was running International Diving and Marine Consulting out of his Miami Shores home and was Marketing VP at Teach Tour Dive. He was also heavily involved with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – the maritime equivalent of National Air And Space Administration (NASA) – as an aquanaut, a saturation diver and a contributor to both the NOAA Diving Manual and the NOAA diving programs, for which he received an award.

His life was about to undergo a radical change. When NOAA Deputy Diving Coordinator Dick Rutkowski retired in 1985, he formed the International Association of Nitrox Divers (IAND) and began to teach sport divers how to blend and use nitrox, which, up to that time, had been used extensively by the scientific and military diving communities, but ignored by the sport diving world. Rutkowski also linked up with Ed Betts in New York to start American Nitrox Divers Incorporated (ANDI).

Having written the first nitrox diver training manual and workbook in 1989, the following year, Rutkowski sold IAND to Tom, although he remained on the Board of Directors.

In the USA in the late 1980s, the activities of various groups of divers who were involved in diving beyond the conventional limits began to gain more prominence. The groups started to coalesce and exchange ideas. Nitrox was part of this conversation, along with deep wreck diving, cave diving, diving on helium-based gases, oxygen decompression, and using rebreathers. A wave was building.

Michael Menduno’s aquaCORPS Journal was the first magazine to focus entirely on what was going on in “beyond-limits” scuba diving and was highly influential in bringing the tribes together. In the January 1991 issue of aquaCORPS, Menduno trialed the phrase “technical diving” as a catch-all term for these activities.

He wasn’t the only one to find this an apt description. Tom took note and added the word “Technical” to the name of his newly acquired training agency, so it became IANTD.

Just as in the late 1960s, when there had been no training agency offering formal education and certification for people who wanted to dive in caves, similarly, when the 90s began, no organisation existed that offered the same for aspiring technical divers. As with cave diving, from a safety and liability point of view, there was an obvious need.

If you had wanted to design an individual to start such an organisation, you couldn’t have done much better than Tom Mount. If he hadn’t existed, someone would have had to invent him. He had a background in building diver training agencies and writing textbooks, he had been diving with rebreathers since the 1950s, deep diving since the 1960s, and working with mixed gas since the 1970s. He also had prestige and status among extreme scuba divers – in 1995, aquaCORPS dubbed him a “gray-beard” of cave diving. (Tom was 56! Already an ancient seer from Menduno’s comparatively youthful perspective.)

Not only could Tom ride this wave, he could get ahead of it and be one of the leaders of the new movement. He added new members to his Board of Directors who would fill in some of the gaps in his skillset and access. IANTD may have been a band in which he could play all the instruments, but he was not a natural lead singer.

The two people he chose fit the bill perfectly: The first, Bret Gilliam, was someone Tom had known since his Andros days. Gilliam was a serial successful entrepreneur with a wide network of contacts, a gift for marketing, and a deep diver who had just set a new world record for deep air diving. Gilliam thought:

“Tom was one of the most skilled divers I had ever met, and we had so much in common.”

In 1992, Gilliam would publish a book called Deep Diving through Ken Loyst at Watersport Publishing and he and Tom would team up to write Mixed Gas Diving for Loyst the following year. These were the first technical diving textbooks, and both became worldwide bestsellers.

The second recruit was Capt. Billy Deans, who had developed mixed gas diving procedures in Key West, Florida, and had been introducing deep wreck divers in the US Northeast to his systems.

Gilliam and Deans were both charismatic figures with front-of-house personalities, big reputations, and connections to parts of the technical diving world beyond the Florida caves – just what Tom needed.

His next task was to develop standards, procedures, and teaching materials for a mixed gas and planned decompression diving training program that could both stand on its own and bolt on to the existing sport diving education pyramid. Tom was in familiar territory. After all, he had already authored training programs for groups as varied as Navy and Army divers, scientists, cave divers and the YMCA.

The entry point was the nitrox diver course, introducing divers to gases other than air. The next step was planned decompression dives; then dives using multiple gas mixes. With each subsequent level dives became deeper and longer.

The top step on the pyramid was trimix diving; that is, diving with a helium-based bottom gas, a travel / first decompression gas and a final oxygen rich decompression gas. This course would certify sport divers to explore depths to 300ft. As Tom told Menduno in his 1995 aquaCORPS interview, it was not something they entered into lightly.

“We had a lot of concerns about trimix when we got started. In fact, Billy [Deans] and I, and a bunch of other people, talked about it for two years. “Do we really want to take the responsibility of certifying somebody as a trimix diver?” There was a lot of trimix teaching going on, but no one had actually said, “You are a certified trimix diver.”

Remember, there was no insurance for this stuff in those days; it didn’t exist. Eventually, we went ahead and developed training programs and standards.”

One of Deans’ early trimix students in the precertification days was author, journalist, and pioneer deep wreck diver Cathie Cush. She remembers that she was one of a select few.

“Billy Deans said that only about 20 divers did his trimix program in 1991, and he had another 20 at a single program in New Jersey in spring of 1992. Of course we wanted to go deeper, stay longer, be safer… And we knew we were pushing it with deep air. We just had to figure out how to do mix in scuba tanks instead of with hoses.”

The technical training pyramid Tom designed became the template that every major sport diver training organisation would follow as they all eventually developed their own technical diving programs.

Magic Beans

Although the word had been in the company name from the beginning, IAND / IANTD had not been very international in its early years. In 1991, that was all about to change.

Word spread beyond US shores that Tom and Co. had the magic beans, and people from all over the world climbed up the beanstalk to Florida. The English speakers came first; the Brits in the vanguard, followed by the Australians. As Kevin Gurr remembers, when he, Richard Bull and Rob Palmer arrived to learn the secrets of mixed gas diving:

“You were taught in Tom’s house and often ended up sleeping with one or two Rottweilers after a long day’s diving. The only text was Dick Rutkowski’s Nitrox Diver; everything else you learned by example… On land the lectures often took the form of open discussion because we were all learning.”

The Brits were planning to start their own pan-European technical diving agency, but in the end Gurr became the first overseas IANTD licensee. Others were to follow: today there are 23 international IANTD licensees covering the entire globe. In the field of scuba diving, this was a groundbreaking business model.

It was also a pain in the neck. From running a small local company, Tom suddenly found himself at the head of a global empire, fighting fires on four continents, trying to maintain quality control among those who came and signed a contract that empowered them to rule their own faraway IANTD kingdom in his name.

Some were worthy acolytes: others proved not to be as reliable as hoped. Selecting the right individuals was very difficult. After all, how can you assess a person’s character and potential on the basis of a relatively brief acquaintance and when you know nothing about them beyond what they have told you themselves? In those days, you couldn’t just Google someone.

Tom decided to judge people by what he could see for himself – how they dived, how they dealt with the cave, and how they understood his ethos. You would not graduate and become part of the IANTD system until you had been “Mounted”, as some called it. Tom would organise huge international gatherings in Lake City, roping in trusted cave instructors, like Larry Green and John Orlowski, to help run the training.

Mostly this technique was successful. Sometimes it wasn’t. Some of the folks who came and took away the magic beans had personal agendas and had to be disciplined, although this was often hard to do at a distance, even with online communications in a flattening world. The mountain is high and the king is far away, as the Chinese say.

The arrival of the Internet meant Tom didn’t have to fly off to other parts of the USA or foreign lands to respond to criticism, deliver rebukes or demand change; he could fly off the handle on an email or in a chat room instead. He never pulled a punch, and some of his exchanges were legendary in their fury. People who had only met polite, smiling, soft spoken Tom in his land-based life were surprised. Anyone who had ever been on the receiving end of Tom’s reaction when they did something wrong in a cave was not surprised at all.

While Tom was teaching disciples, building a network, fighting online battles, wrestling technical diving into manageable shape, and making sure his training programs had legal footing, he had a solid team behind him in the office, led by Patti, son David, and Don Townsend.

By 1995, Menduno, writing in aquaCORPS, summed up the state of play thus:

“It wasn’t too long ago that technical diving was regarded as the lunatic fringe of sport diving… “You’re going to do what?”

Enter Tom Mount. In less that five years, the 56 year-old former U.S. Navy diver… and one of the graybeards of the NACD… has built the world’s largest technical diving agency, pulling together the lion’s share of the “big names’ in more than a dozen countries under the IANTD banner. Considering the egos involved – no small feat indeed.

Under Mount’s leadership, IANTD has created a structured series of technical diving courses and training standards, has nailed down an insurance program providing coverage at depth and spun off at least one other agency.”

This “spun off” agency was Technical Diving International (TDI), established in 1994 by Bret Gilliam and Mitch Skaggs. It too would come to span the world.

Acceptance

Industry acceptance of technical diving—something Tom and others had fought hard for—was cemented in the late 1990s, when the mass-market training agencies expanded their range to include nitrox and technical diving, but this victory brought its own challenges. IANTD, TDI and ANDI no longer held a monopoly. Nevertheless, the IANTD empire continued to grow, especially overseas. In the beginning, of course, the USA had been the most successful office in terms of certification numbers. A few years later, it was Central Europe. Then it was Korea. The fulcrum of scuba diving was moving east and the licensee business model meant that IANTD was there already. Another consequence of the expansion was that Tom started travelling further afield to run courses in places such as Pattaya, Thailand and Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

Deans eventually hung up his fins, and US Navy Commander Joe Dituri came on board as a director. In 1998, Tom published the Technical Diving Encyclopaedia, which would become the seminal text for a new generation of advanced divers, just as Mixed Gas Diving had been for their predecessors.

In 2000, the Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences honored Tom with a NOGI award for Sports Education. Movie director and fellow NOGI awardee James Cameron described getting a NOGI as “the underwater equivalent of winning an Oscar except a lot harder!”

In 2005, after a hectic 15 years at the helm of IANTD, retirement seemed to be in the cards, as the company was sold, only for the deal to fall through in traumatic fashion. Dituri, the international licensees and old friends kept the wagon rolling and Tom eventually returned to pick up the reins. It was not until 2015, when Luis Augusto Pedro came on board as COO, that Tom could move out of the front line and spend more time with wife Gexa.

Nevertheless, he remained CEO and figurehead, he was still often spotted wading into the ocean with a new rebreather model on his back and he was still writing until well into his seventies.”The titles of the Tao of Survival Underwater (2008) and the Tao of Cave Diving Survival (2016) show how, over 50 years, the times might have changed, but the basic themes and messages remained the same.

By now, he could genuinely enjoy being a “gray-beard,” accepting further awards and speaking invitations and, as his Facebook page shows, attending events and meetings and befriending yet another crop of technical divers – the only difference being that this new generation demanded selfies.

Tom Mount RIP.

Sources

Tom was never one to blow his own trumpet. He did not write an autobiography, rarely agreed to interviews and, when asked to supply an author or speaker biography, usually did no more than list his awards and accomplishments. This piece has been compiled from a host of sources, including personal memories, recollections of conversations with Tom over the years, input from some of Tom’s friends and colleagues, and details of Tom’s life and opinions gleaned from books and the few interviews he did give.

DIVE DEEPER:

Facebook: Tom Mount

Wikipedia: Tom Mount

IANTD: Training with Tom Mount Classes (Wayback Machine 1997)

PSAI: Tom Mount and PSAI

aquaCORPS: You’ve Come A Long Way Baby: Tom Mount Talks Tech by Michael Menduno (1995)

Divernet: The Technical Diving Revolution – part 1 by Michael Menduno (2019)

Divernet: THE TECHNICAL DIVING REVOLUTION – PART 2 by Michael Menduno (2019)

Amazon.com: Deep Diving: An Advanced Guide to Physiology, Procedures and Systems, by Bret Gilliam, Robert Von Maier, John Crea

Amazon.com: Mixed Gas Diving: The Ultimate Challenge for Technical Diving by Tom Mount, Bret Gilliam et al

Amazon.com: Technical Diving from the Bottom Up, by Kevin Gurr

Simon Pridmore was a pioneer of technical diving in Asia. Today, he is one of diving’s most prolific writers, with a five volume Scuba series, several guides for travelling divers, a biography and even a couple of divers’ cookbooks to his name. He is currently working on a new book called Technically Speaking, a collection of talks about technical diving, including the history of tech, what went before, how it came about and why things developed the way they did. Learn more about Simon and his books on his website or via his Scuba Conversational newsletter.