Cave

To Wes: A Tenacious Advocate Committed to Protecting Florida’s Springs

By Todd Kincaid. Header image: Down the river from Ginnie Springs, the pure spring water collides with the tannic-stained surface water of the Santa FeRiver. Photo by Wes Skiles. This photo appeared in the National Geographic story, “Unlocking the Labyrinth of North Florida Springs,” published in March 1999,

I’ve been humbled several times in my life. I like to think I’ve learned and grown from each one of them. One of those times was in March 2007. Wes and I were both working as consultants to Coca Cola to develop a computer model of groundwater flow to the springs on the western Santa Fe River. We were both partners in small companies that we’d started to pursue our passions for springs and caves and karst.

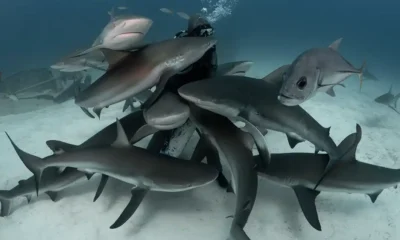

Wes and his team had, by then, been working for at least 20 years on physical measurement of spring flows, cave passages, and groundwater flow paths across much of North Central Florida. In the tiny world of Florida hydrogeology, they were the go-to resource for work on the springs. At the time, Wes was better known to most for his underwater cave filming and photography, which by then had included the documentary film: Water’s Journey, The Hidden Rivers of Florida, which is, in my opinion, still the best depiction of cave diving and groundwater flow to springs that has ever been made.

My team and I were comparative Johnny-come-latelys. We’d started our company in 1999 intent on building better computer models of groundwater (and contaminant) flow to springs. I was confident—some might say cocky—in my knowledge of groundwater flow across the Santa Fe River area having studied the area intently for several years, both as a hydrogeologist and as a cave diver. Besides, I was part of a team of young, enthusiastic, and wicked smart hydrogeologic modelers.

Protecting Ginnie Springs

Coca Cola had hired both of our teams to help them devise a plan to protect the quantity and quality of groundwater flow to Ginnie Springs, and in so doing the source of water for their bottling operation in High Springs Florida. I’d organized a field trip to the Santa Fe River for our collective technical staff as well as key Coca Cola personnel to demonstrate why our team needed to focus on the entire basin (~1,930 km2 or 750 mi2) as opposed to just the area around the water bottling plant and Ginnie spring. The reason being that in order to achieve their goal, Coca Cola would have to succeed in a sociopolitical effort to change the way groundwater was managed in at least the Santa Fe River basin, and to do that, they’d need to address big picture problems and concepts.

Pete Butt, Wes’s business partner, and I were leading the trip. We had gathered at a picnic table behind the dive shop at Ginnie Springs to go over our agenda with the group and to get some thoughts on flow patterns and key sites from Wes. Wes started out in an unassuming but direct manner that I would come to know as his style. He rolled out a ragged set of 1:24,000 scale topographic maps that spanned most, if not all, of the western Santa Fe River basin (perhaps as many as 15 maps, each measuring about 58 cm or 23 in on each side). These mapshad been taped together and annotated with notes and lines and numbers penned over what must have been years or even decades. Wes had recorded on those maps every foot of underwater cave passage that he’d explored and mapped along with arrows pointing out the direction of flow and notes about the water clarity and velocity as well as sediment conditions that he had observed. Countless lines marking passages in tens of caves, most of which I didn’t even know existed, much less had been explored and mapped. I’d never seen Wes’s map before, nor anything like it, and a few things were immediately apparent.

One, that here was a guy who had not only expectedly and immeasurably exceeded my level of experience in cave exploration but also, more significantly, far exceeded my dedication to documenting what he’d seen and learned. Two, that despite never being trained as a hydrogeologist, he’d clearly developed a more detailed understanding of groundwater flow through the basin than I had or any hydrogeologist I’d ever met. And three, that something must have gone terribly wrong in my profession for a map like this to exist but not even to be known or much less published and used as the guide that it so clearly should be.

It was a watershed moment for me. I saw before me a map that I’d hoped to make myself but that already existed. I remembered the times when Wes had come into our hydrogeology classrooms at the University of Florida to show videos of the caves that I took for granted but never spoke of in school; of the days when professional hydrogeologists came to those same classes from the various resource management agencies and told us that caves didn’t exist or were irrelevant in the practice of groundwater science, that professionals studied wells but amateurs studied springs, and that Wes must surely have fabricated his cave videos – Hollywood style.

In later years, Wes told me of the repeated trips he’d made to those agencies, with his maps and videos in hand, trying to show people where the water came from, where it was being contaminated, and where it needed to be protected. To the discredit of my profession, he also told me of being dismissed for not being educated enough to understand hydrogeology. I’m sure it made him mad but just as sure that it made him laugh, and to be able to laugh in the face of adversity is a truly admirable quality.

A Committed Advocate

It is within and amongst the springs, places that have been described as pools of liquid light, that he carved out a life, made a home, and inspired countless people around the world. Wes was a truly committed advocate for springs protection. Not the type of advocate who prattles on emotionally with what he described as misguided animosity about things they’re unwilling to truly understand. Instead, he was the type of advocate who brings to the table a lifetime of intimate knowledge that stems from an insatiable curiosity and a tenacious quest for answers. He understood springs for what they truly are, spiritual places of extraordinary beauty to be sure, but also keystones to the fabric of Florida’s water supply. Features that must be preserved if the aquifer, on which so many people and industries and ecosystems depend, is to remain intact, functional, and sustaining. In his uniquely engaging way, Wes spoke of Florida’s springs’ importance to all who were smart enough to listen.

Despite being ignored for so many years, Wes accepted every opportunity to engage with politicians and decision makers about the need for springs protection and to teach people of all ages and pedigrees about Florida’s springs and the caves from which their waters flow. Jim Stevenson, who served as Chief Naturalist of Florida’s State Parks for 20 years, appointed Wes to the first Florida Springs Task Force in 1999 where he served tirelessly to say what needed to be said, as Jim puts it, “despite political sensitivities” that muzzled most other voices. He spoke truth to power seemingly without regard for consequences.

I am fortunate to have known and worked with Wes and am sure that like many others will always wish that there could have been more time. Wes helped me from the beginning of my career when so many suggested that I was wasting my time in the caves. While the professionals spoke to me from the comfort of their offices about slow and ancient groundwater impervious to depletion or degradation, Wes invited me to join him to actually see and measure the flows for ourselves.

An Inconvenient Truth

On a scorching Florida day, in advance of a two-day thunderstorm, together with friends and neighbors constituting his tribe, we dragged scuba tanks and dyes and special gasses and hundreds of feet of tubing deep into the woods above Ichetucknee Springs to inject our tracers into the veins of Florida’s blood supply. Several days later, after leaving the comfort of our soaking wet tents every 30-60 minutes to collect samples from the springs, we had hard data that speaks to Florida’s very own inconvenient truth – that groundwater flow is fast and that the quantity and quality of Florida’s water is very highly dependent on what Floridians are doing at the land surface. It’s a truth that Wes and his team proved time and time again through their work as hydrologists, despite their lack of formal education. If the saying common in engineering is true that one test is worth 1,000 expert opinions—then Wes and his team have surely contributed more to our understanding of Florida’s groundwater than many 1000s of experts.

Wes never stopped scheming about the next opportunity to show people the truth. In one of my last conversations with him, he told me about how frustrated he was with his work on the Water’s Journey series, particularly the last installments where he felt restrained in his ability to call attention to what he believed to be the culprits of Florida’s deteriorating springs. He also told me of his plan to get funding for a new series about the springs in which he could tell the story that he wanted to tell the way he wanted to tell it. Despite his many successes, I don’t think he was ever satisfied enough to rest on his laurels. He was forever exploring and pushing for the next adventure. If only there could have been more time.

I’m sure Wes would be flattered to see his name adorn the entrance sign to Peacock Springs State Park. I’m equally certain though that he’d be less than happy with the current state of Florida’s springs, including his namesake. So, if we really wanted to honor Wes, we would let Florida’s officials know that a spring bearing Wes Stiles’s name should be clean and flowing strong and a symbol for what other springs in Florida once were and could be again.

So, here’s to Wes! He is missed and he will forever remain an inspiration to anyone with a bit of adventure in their hearts – to keep diving, keep trying, keep laughing.

To explore more stories, documentaries, videos and articles by and about Wes Skiles click here: Celebrating Wes Skiles

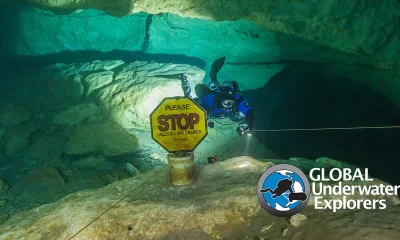

Todd is a groundwater scientist, underwater explorer, and advocate for science-based conservation of water resources and aquatic environments. He holds BS, MS, and Ph.D. degrees in geology and hydrogeology, and is the founder of GeoHydros, a consulting firm specializing in the development of computer models that simulate complex hydrogeologic environments. He has been an avid scuba diver since 1980 having explored, mapped, and documented caves, reefs, and wrecks across much of the world. He helped start the diving organization Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) in 1999 and served on its Board of Directors and as its Associate Director from its inception to 2018. He started Project Baseline with GUE in 2009 and has been the organization’s Executive Director from its beginning.