Conservation

The UB-88 Cleanup Project

US affiliate Ghost Diving USA reports on their successful removal of 900 kg/2000 lbs. of ghost nets from the WWI German submarine, the UB88 lying at a depth of 58m/190 ft near San Pedro, California. President Jim Babor and marketing manager Gözde Akbayir share the details of this challenging, historical 2024 project that involved research, photogrammetry, and some formidable ghost diving! Thank you GUE volunteers!

by Jim Babor and Gözde Akbayir. Images courtesy of Ghost Diving USA.

The UB-88, a World War I German Type UB III submarine, rests quietly on the ocean floor off the California coast, bearing witness to over a century of history. Surrendered to the United States on November 26, 1918, the submarine traveled across the Atlantic and through the Panama Canal before being intentionally sunk during naval exercises on January 3, 1921. Today, it lies approximately 12 km/7.5 miles south of San Pedro, California, at a depth of about 58 m/190 feet. As the only known German U-boat on the U.S. West Coast, the UB-88 serves as both a historical wreck and an artificial reef.

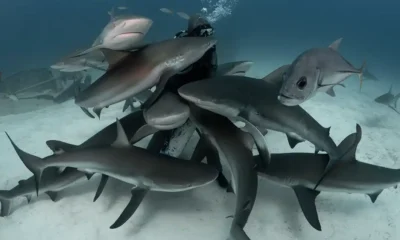

In 2024, this remarkable wreck became the focus of a major environmental cleanup effort aimed at removing ghost fishing nets, which endangered marine species and obscured the site. Over five intensive days in December 2024, Ghost Diving USA volunteers worked to restore this underwater landmark, remove hazardous material, and promote marine conservation.

The groundwork for the UB-88 cleanup project started months earlier, in January 2024, with a series of survey dives that laid the foundation. These dives were crucial for assessing the wreck’s condition and understanding the extent of the ghost net problem. During the first dive on January 24, the team captured thousands of images to document the site in detail and to begin the process of making a photogrammetry model of the wreck.

Further dives in February and April built on this work, refining the data and completing a thorough visual survey. Divers carefully mapped the wreck, noting how nets were tangled within its structure and buried in the surrounding sand. These efforts provided the team with a clear understanding of the challenges ahead and formed the basis for planning the December cleanup operation.

Planning and preparations

Preparation for the UB-88 cleanup project took months of planning and logistical coordination. With the operation scheduled for December 16-20, securing the necessary resources and assembling a capable team was a top priority. Two vessels, the Giant Stride and the Bottom Scratcher, captained by Jim Simmerman and Kevin Bell, respectively, were secured to serve as the project’s base of operations.

Funding and support came from a diverse group of sponsors and collaborators, including Healthy Seas and Hyundai Motor America. Healthy Seas, a foundation dedicated to addressing the issue of marine litter, particularly fishing nets, works to promote healthier seas and repurpose waste into innovative products through collaboration with partners. Hyundai Motor America’s involvement as a main sponsor underscored their commitment to environmental sustainability and marine conservation. Their contributions, along with numerous grants and private donations, made this cleanup project possible.

Building the right team was just as important as securing resources. A dedicated 12-person dive team was assembled, including technical open-circuit and JJ–CCR rebreather divers, along with five safety divers. They were supported by a nine-member surface team that handled essential logistics. Jamie Mitchell from Zen Dive Co. ensured a steady supply of tanks and gas, while the surface operations ran smoothly thanks to a collective effort from everyone involved.

As part of the preparation, the photogrammetry model created earlier in the year played a crucial role. It was used to produce a 3D-printed model of the site and the wreck, which helped the team plan every aspect of the cleanup. The model was also utilized during briefings to visualize the wreck’s structure and the placement of ghost nets. Beyond its practical use, the model serves as a powerful outreach tool, bringing the underwater world of UB-88 to life for a wider audience.

With the logistics in place, a strong team ready, and a clear action plan, the stage was set for the UB-88 cleanup operation.

Staging and documentation

The operation kicked off early on December 16, with the team setting off on a 90-minute journey to the UB-88 wreck site. Ghost Diving USA CEO and President Jim Babor led a detailed briefing to outline the day’s objectives. To help orient team members less familiar with the site, the 3D-printed model created from earlier photogrammetry work played a pivotal role in pre-dive briefings. The focus for Day 1 was twofold: staging equipment for the upcoming net removal dives and initiating a substrate study, led by Norbert Lee, to evaluate the ecological impact of ghost nets on the wreck.

During their 35-minute bottom time, the divers captured critical baseline photographs to document the wreck’s pre-cleanup condition. Divers used a custom hang bar for secure decompression stops in the open water of the busy shipping channel.

Full-scale net removal

Day 2 kicked off with the team diving into full-scale net removal. To avoid overcrowding in the tight underwater space, the teams worked in shifts.

Team 1 started by carefully moving fragile marine life, like Metridiums, out of the work area. They then attached lift bags to sections of the nets to prepare for removal. Team 2 focused on clearing the nets from the port and starboard sides, with David making a special effort to free fish and crabs trapped in the debris. Team 3 worked on cutting the lower sections of the net.

The highlight of the day was successfully removing a 225 kg/500 Ib section of fishing net. The Giant Stride, serving as a chase boat, recovered the net once it surfaced, while safety divers helped keep everything running smoothly underwater by checking on the working divers at their 21 m/70 ft and 6 m/20 ft decompression stops and taking extra equipment from the working divers as needed. This marked the first big milestone of the cleanup, with the team’s coordination and teamwork really standing out.

Record-breaking haul

The team faced one of their toughest challenges on Day 3: removing the largest entangled net on the UB-88 and clearing the torpedo tube.

During their dives, the teams tackled a massive 680 kg/1,500 Ib fishing net—marking the largest single haul in the team’s history. The size and weight of the net turned this achievement into a true test of teamwork. To coordinate this day of diving the first team descended to stage final lift bags on the massive amount of net. Thirty minutes later the cutting team, which consisted of Karim, Curtis, and Jim descended and started cutting for their planned bottom time of 35 minutes.

Despite the effort and complexity, the results were worth it. By the end of the day, the wreck was completely free of ghost nets. The remaining net now lay on the sand, beneath the stern of the wreck.

Remaining hazards

Day 4 shifted the focus from large-scale net removal to addressing remaining hazards and documenting the environmental impact. Some nets still posed a risk due to their buoyancy in the sand, creating potential entanglement hazards for marine life. The divers carefully gathered these remnants into one area and secured them with lift bags for easier removal later. The teams also secured sections of net rope cinches to bundle large sections, attaching lift bags with the plan to return on the final day and cut as much net free as possible.

One major challenge the team faced was from steel cables tangled within the nets, but they made steady progress in preparing the site. Meanwhile, Norbert and the science team continued documenting the wreck, photographing both the untouched and damaged parts.

Wrapping up

On the final day of operations, the team focused on trying to cut the net that had been prepared the day before and leaving some extra time to wrap up tasks to leave the site in a safe, prepared state. They cleared the wreck of tools and equipment and prepared any remaining nets for later removal. The steel cinch cables proved problematic in making progress with the nets that remained, and no net was recovered that final day. Despite this, by the end of the day, the wreck was fully cleared, environmental documentation was completed, and all salvageable nets were handed over to a local partner for recycling.

Achievements

Over five days and 15 dives, the UB-88 cleanup project removed around 900 kg/2,000 Ib of ghost nets. The operation cleared the wreck, but it also kicked off a long-term scientific study to better understand the effects of nets on underwater habitats. A large portion of the recovered debris was sent to a facility for recycling, supporting efforts to create sustainable solutions to marine pollution.

This project highlighted the power of collaboration among various stakeholders, including divers, surface crew, media, and sponsors. Looking ahead, the team plans to return with specialized tools to tackle the steel cables and finish removing the remaining nets. The first phase of the UB-88 cleanup project has made significant progress in marine conservation, showing the positive impact of teamwork in preserving both historical artifacts and marine ecosystems. While there is still much work to be done, this effort serves as a valuable example for future conservation initiatives.

FACT FILE // SCIENTIFIC STUDY

By Norbert Lee

Abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), also known as ghost nets, can cause significant harm to marine environments. These nets result in unintentional fishing (when marine life becomes trapped), ingestion of microplastics by wildlife, smothering of benthic organisms, and surface damage from the nets moving in the water. In Southern California, where Ghost Diving USA operates, strong tidal currents contribute to the movement of ghost nets, which scrape against shipwrecks and ocean floors, causing further ecological harm and disrupting the habitat of benthic communities.

The UB-88 Cleanup Project aimed to evaluate the impact of removing ghost nets and whether doing so could help restore habitats by allowing new life to settle on surfaces previously affected by the nets. The goal was to see if removing the nets from the torpedo tube and other areas would support ecological recovery by creating space for marine life to return.

Background of the net in question

During the UB-88 cleanup, the team focused on a ghost net located on the submarine’s aft torpedo tube. This net, suspended by a float, was frequently moved by currents, causing abrasion on the tube’s surface. This presented a valuable opportunity to compare affected areas with those not impacted by the nets, offering insights into how ghost nets damage surfaces and whether removal could encourage recovery.

Methods

The UB-88 Cleanup Project aimed to monitor changes at the wreck site while minimizing disturbance. Before removing the ghost nets, the team marked their original positions. A visible line was then installed across the torpedo tube to serve as a reference, with stations set at intervals using numbered markers, or “cookies.” The team set up five stations in areas impacted by the ghost nets and five in unaffected areas.

To track changes, the team used 0.5 x 0.5-meter photo quadrats to capture images of invertebrates and assess the coverage of colonial invertebrates in each area. These images were critical in documenting the condition of the site before and after net removal.

Discussion

While the study provided valuable insights, it was limited by the small area affected by the nets, as well as the challenges of working at a depth of nearly 61 m/200 ft . To better understand the long-term effects, the team plans to return periodically, if funding allows, to continue monitoring changes. This ongoing research could form the foundation for a more extensive marine conservation project, providing important data on how ecosystems recover after ghost net removal and informing future efforts to clear marine debris.

References

– Gilman, Eric, et al. “Introduction to the marine policy special issue on abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear: Causes, magnitude, impacts, mitigation methods and priorities for monitoring and evidence-informed management.” Marine Policy, vol. 155, Sept. 2023, p. 105738, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105738.

– Macfadyen, Graeme, Huntington, Tim, and Cappell, Rod. (2009). Abandoned, Lost or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear. UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies. 185.

FACT FILE // HISTORY OF UB-88

UB-88, a German submarine from World War I, was built in 1917 and commissioned in 1918. Armed with torpedo tubes and a deck gun, she was designed for stealth and assigned to the I U-Flotille Flandern based in Zeebrugge, Belgium. During her active service, UB-88 sank several Allied vessels, including the British steamer Princess Maud and the Swedish Dora. Despite facing intense counterattacks, UB-88 successfully completed her missions.

After Germany’s surrender in 1918, UB-88 was handed over to the U.S. as part of a Victory Bond drive and to study German submarine technology. She toured U.S. ports to promote war bonds before being decommissioned in 1920 and scuttled in 1921.

Rediscovered in 2003 near Long Beach, California, UB-88’s wreck has since become an important historical and archaeological site, offering insights into World War I submarine warfare.

FACT FILE // TEAM MEMBERS

Angie Biggs, Curtis Wolfslau, Daniel Pio, David Watson, Jamie Mitchell, Jim Babor, Juan Torres, Jung-han Hseih, Karim Hamza, Katie McWilliams, Kian Farin, Laurie Dickson, Mark Self, Michael Gasbarro, Nir Maimon, Norbert Lee, Rene Tetter, Shane McWilliams, Symeon Delikaris Manias, Tianyi Lu, Yury Velikanau & Katie Papac

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Restoring Marine Life: The UB-88 Project Tackles Ghost Nets on a Historic World War I U-Boat

InDEPTH: Resurrecting a Ghost: The Launch of Ghost Diving USA by Katie McWilliams

InDEPTH: Ghost Diving the Paddleship Patris By Symeon Manias and Curtis Wolfslau.

Alert Diver: Ghost Fishing by Michael Menduno

Jim Babor is a classical musician and has been a member of the Los Angeles Philharmonic since 1993. Jim is also a professor at the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music. He is also an accomplished technical and cave diver and holds certifications from GUE for cave, technical, and rebreather diving.

As for Ghost Diving, Jim has been very generous in donating his time since 2012. He is the current CEO of Ghost Diving USA and has helped propel the organization into one of the most active chapters in the world, as well as aided in the establishment of Ghost Diving USA, an official 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation, to further the cleanup of coastline around the USA.

Gözde Akbayir is the Media & Marketing Manager for Ghost Diving USA and the Marketing Coordinator for GUE. With over 15 years of experience managing a dive center, travel agency, and marketing initiatives, she brings her extensive expertise and love for the ocean to her work. Certified as a trimix instructor, and CCR and cave diver, Gözde specializes in digital marketing, community management, and content creation within recreational and technical diving. She holds degrees in management and finance, which complement her professional focus. Originally from Türkiye and now residing in Malta with her family, Gözde draws constant inspiration from the sea. Through her roles with Ghost Diving USA and GUE, she is dedicated to supporting marine conservation efforts and amplifying awareness of environmental initiatives.