Exploration

The Santa Barbara Helium Rush—The Legacy Of Dan Wilson’s 400-foot Gas Dive

Roughly 25-years before the emergence of tech diving, commercial divers were pushing the limits of “deep air” as offshore oil fields grew steadily deeper. That is, of course, until 1962 when 33-year old Santa Barbara abalone diver cum entrepreneur Danny Wilson made his 123m/400ft dive on heliox paving the way for the commercial mixed gas revolution. Professor Don Barthelmess reflects on Wilson’s Big Dive!

By Don Barthelmess

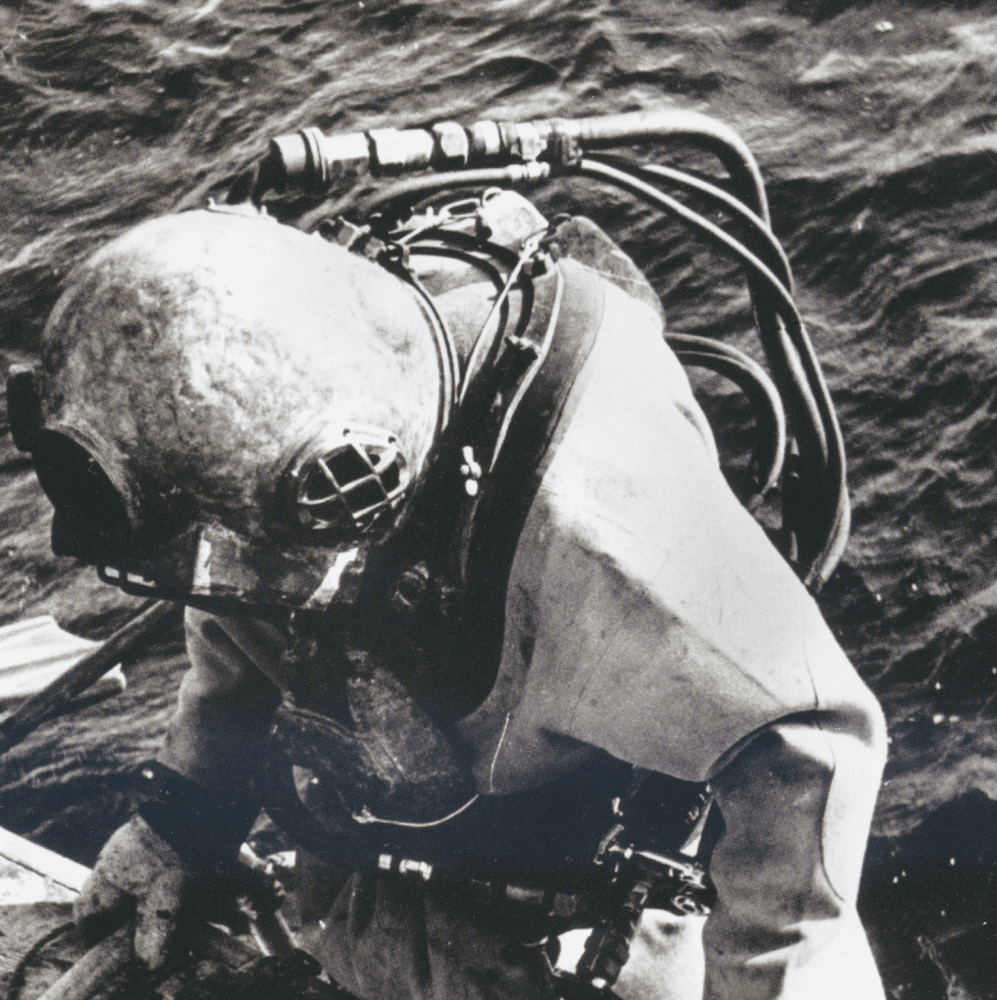

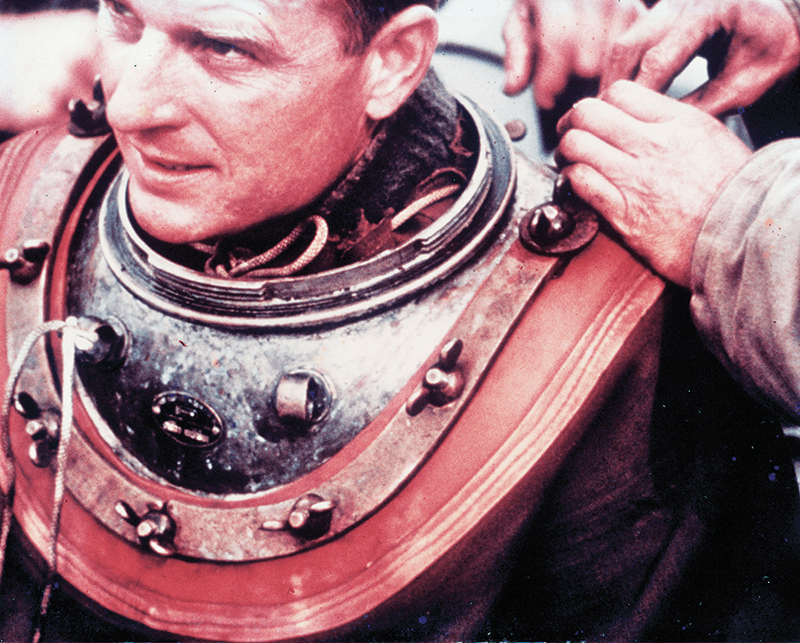

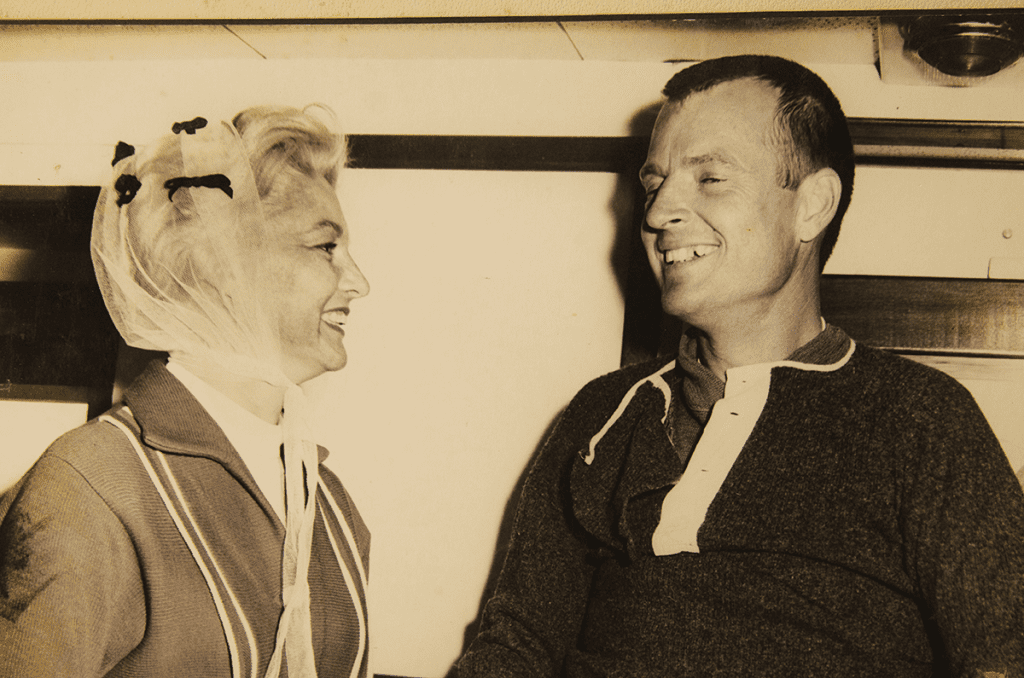

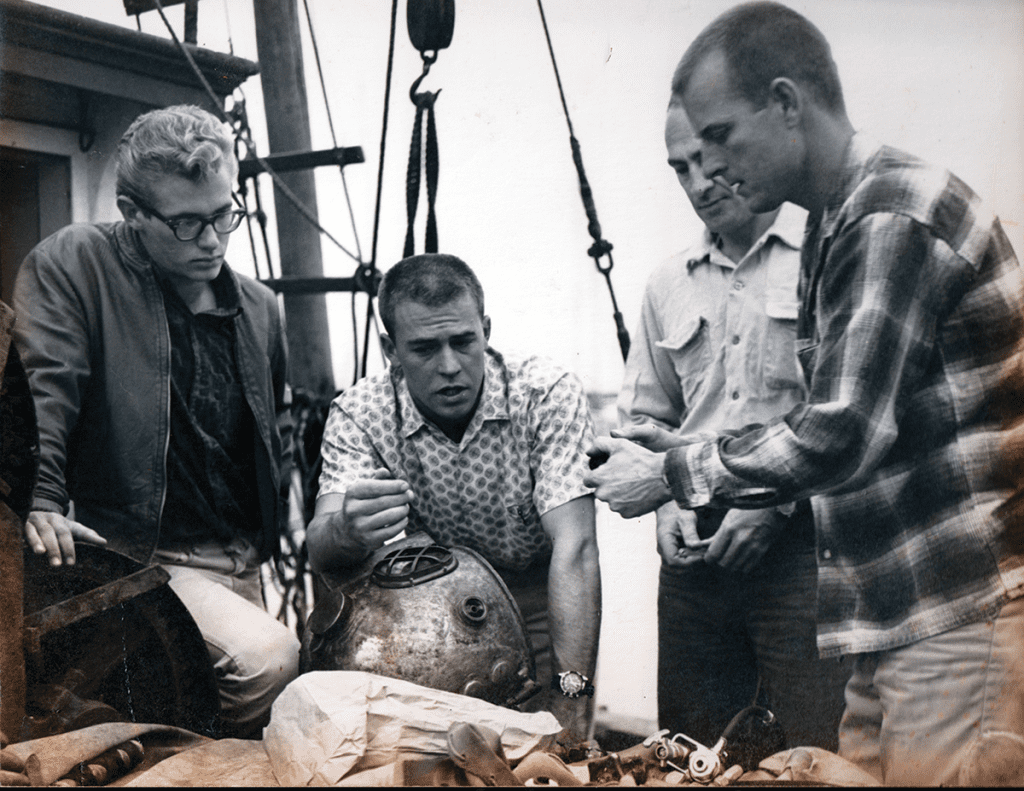

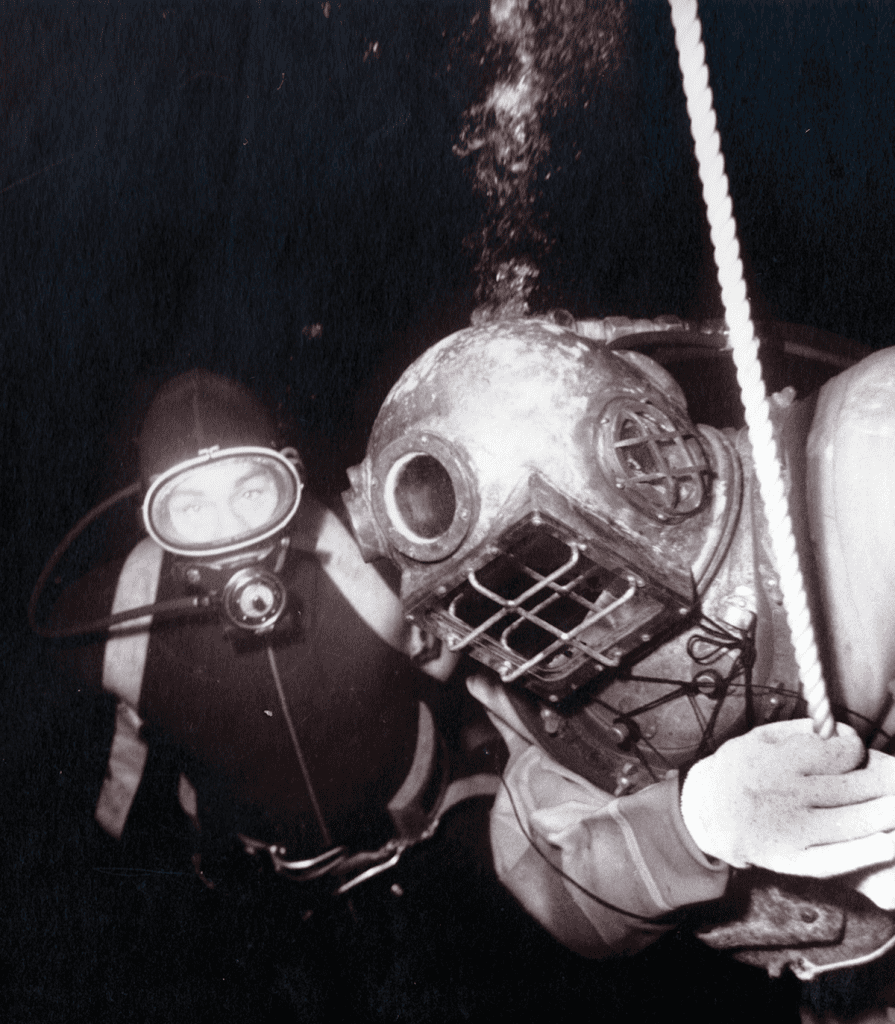

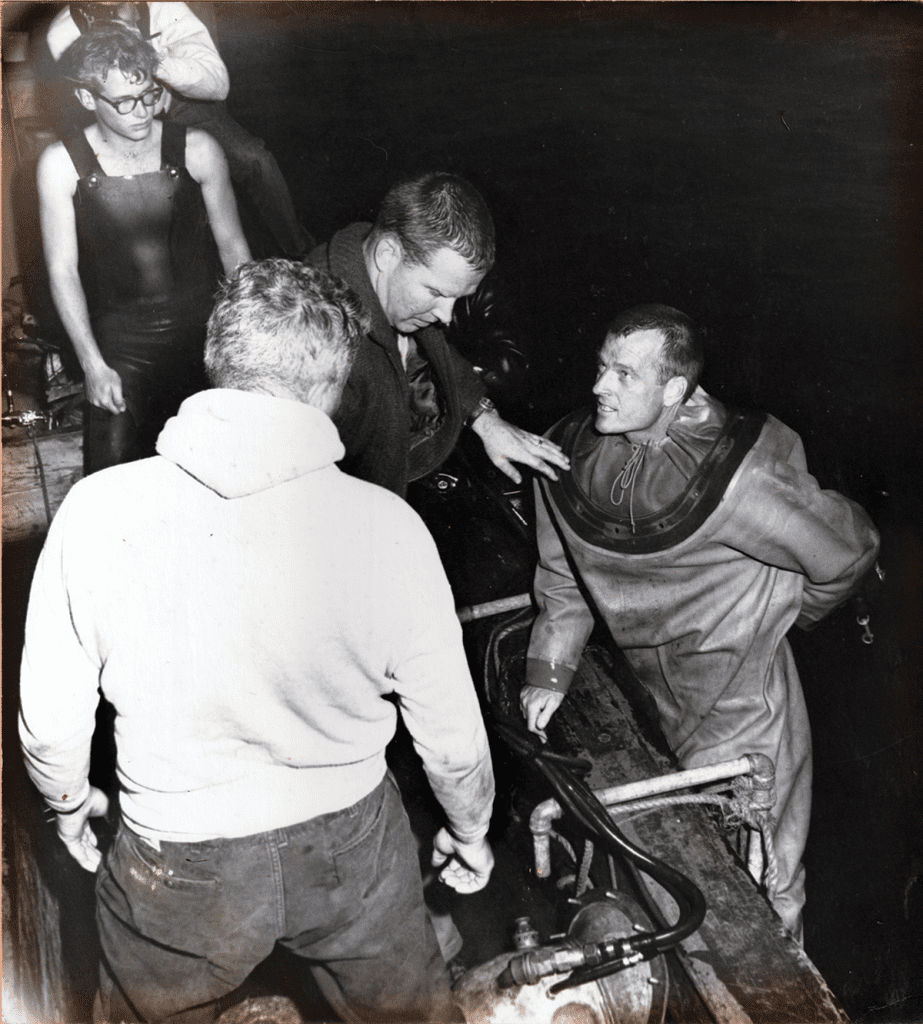

Header image: Wilson in the modified helmet prepares to make his historic dive, November 3, 1962. The scuba regulator first stage, clamped to the USN belly valve, is shown at his waist under his left arm.

The roots of commercial deep water diving technology are firmly embedded in Santa Barbara. This year marks the fiftieth anniversary [2012] of a significant, historic dive that revolutionized commercial diving and the expansion of offshore deep water oil exploration.

In 1962, 33-year old Santa Barbara commercial abalone diver Hugh “Danny” Wilson saw a need for the commercial use of mixed gas diving techniques in order to position himself for offshore petroleum exploration diving support. On November 3, 1962, he dived to over 123m/400 ft off the east end of Santa Cruz Island in the Santa Barbara Channel, using oxy-helium or heliox as a breathing gas.

The dive became a catalyst for the worldwide expansion of commercial diving and equipment in deep water. It created what I refer to as “The Santa Barbara Helium Rush”. It also established Santa Barbara as the birthplace of deep water industrial diving and techniques. Numerous Santa Barbara area residents pioneered and contributed to this evolution of diving and the technology associated with it.

I first heard of Dan Wilson in 1979 as a young student of Commercial Diving and Underwater Technology at Florida Institute of Technology. I vividly remember the class, Mixed Gas Diving Techniques I, taught by ex-U.S. Navy diver Doug Soule and Master Chief Frank “Doc” Irwin. The very first classroom session focused on the history of gas diving. We learned about Wilson’s dive and the specifics of how he used established Navy procedures yet wisely abandoned using the awkward US Navy Mark V gas re-circulator helmet.

Chris Swann writes extensively of Wilson’s historic dive and these pioneering individuals in his seminal work published in 2007, The History of Oilfield Diving: An Industrial Adventure. Many of these men went on to become familiar historic icons and to develop our industry: names such as Bob Kirby, Bev Morgan, Lad Handelman, Whitey Stefens, Bob Christensen, Bob Ratcliffe, Murray Black, Woody Treen, the Benton Brothers (Bob and Ted), Hughey Hobbs, Bob Rude, Jerry Todd, and Walt Thompson—to name but a few.

Wilson made the dive to prove a point to oil companies drilling offshore in the Santa Barbara Channel in the 1950s and early 1960s. The oil companies needed deep water diving support for their exploratory operations beyond 92m/300 ft. Up until the 1960s, drilling took place in relatively shallow water. Petroleum geologists knew that vast reserves were beyond 92m/300 ft yet could not drill at those depths without diving support.

Although just a short distance from the coastline, operators soon found themselves in depths greater than 77m/250 ft, as the continental shelf lies very close to the Santa Barbara coastline. This was beyond the physiological range of air diving primarily due to oxygen toxicity and nitrogen narcosis, not to mention the long decompression times. [Ed.note: Commercial divers use diving helmets and surface supplied gas, which alters the risk profile of potential oxygen toxicity and narcosis somewhat, i.e., they would not drown in the event of a convulsion or loss of consciousness.]

Air Vs. Heliox

When breathed under pressure the nitrogen found in air is narcotic. Cousteau referred to this as “rapture of the deep.” In essence, it is similar to being intoxicated. Susceptibility to this effect varies among individual divers; however, most feel the effects beyond 30m/100 ft.

With requirements to dive beyond 61m/200 ft came the challenge of actually accomplishing work with a “narked” diver. Narcosis is a very real occupational hazard for a deep working diver. It is exacerbated by cold and physical work under water. Oilfield diving in deeper waters had a new challenge. The nitrogen had to be removed from the breathing mixture.

The dominant diving company in the area at that time was Associated Divers, an exclusive conglomerate of abalone and construction divers from Santa Barbara and Southern California. Since standard dress or heavy gear was the diving mode used, the narcotic effects of air limited the divers. Additionally, relatively short bottom times and the potential for acute central nervous system (CNS) oxygen toxicity further limited work in deep water.

Dan Wilson was a far-seeing individual who thought outside the box. Most importantly, he acted on his ideas. According to his son Dan, “Dad kept meticulous notes on his ideas and had a passion for science and technology throughout his life.”

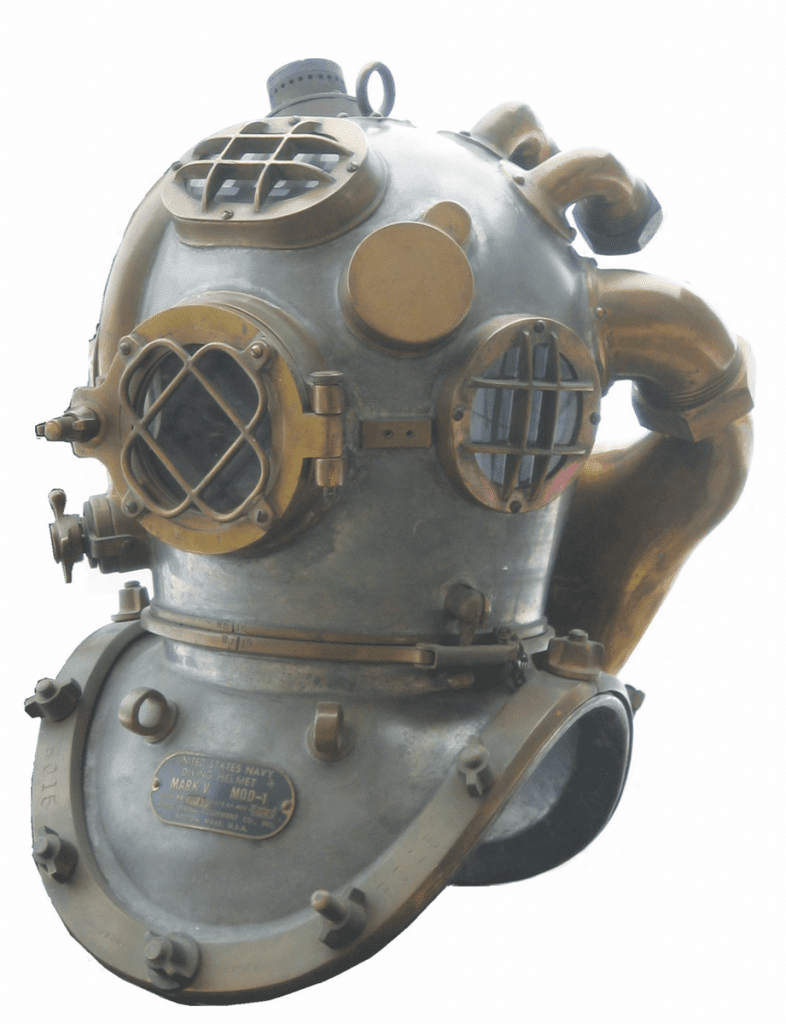

He received his diver training from legendary U.S. Navy Master Diver E.R. Cross at the Sparling School of Deep-Sea Diving. It was there that Wilson learned about the U.S. Navy’s use of helium for deep diving to overcome the narcotic effects of air. He was also aware of the trade-offs and risks associated with helium diving, including the cumbersome 250-pound/113 kg U.S. Navy Mark V helium gas re-circulator helmet.

The first to suggest the use of helium and oxygen as a breathing mixture for diving was American physicist and chemist Elihu Thomson in about 1919. Up until the 1960s, the U.S. Navy led the way in heliox diving techniques. Being an inert gas, helium does not act as an anesthetic when breathed under pressure.

The trade off of nitrogen for helium was not without other physiological and logistical consequences. Helium was expensive and had to be specially mixed with oxygen in the right proportions depending upon the depth. This was to avoid the onset of oxygen poisoning, which is not normally a risk for air diving shallower than 67m/218 ft [Ed.note: PO2 less than 1.6 atm. Note that helmeted divers have a slightly different risk profile than scuba divers).

Helium is a more diffusible gas in the diver’s tissues, as a result, in-water decompression required deeper and more specialized decompression techniques (Today that view is changing. See: Eliminating The Helium Penalty), including a surface decompression chamber. Furthermore, heliox mixtures quickly rob divers of heat through respiration, as it conducts heat some six times faster than air. Thermal protection was a concern, as divers quickly became cold just from breathing the gas at depth. Lastly, voice communication was awkward, as the speed of the helium molecules traveling across vocal cords made the diver’s voice sound like Donald Duck over the hardwired communication radio.

Until 1962, Wilson worked as a commercial abalone diver. However he had a burning financial desire to break into Santa Barbara oilfield diving, which was exclusively closed off to newcomers by Associated Divers who were considered the “King Kongs” of oilfield diving at the time. He wondered why Associated Divers did not use helium to access deeper depths, and though the company was aware of the Navy’s use of helium, they never implemented it in their work due to the logistics and expense.

Additionally, they were profiting quite nicely from their monopoly on deep air diving. According to fellow abalone diver Lad Handleman, who went on to co-found and serve as CEO of Oceaneering, Associated’s divers were capable of conducting working dives for up to 25-minute bottom times at 77 m/250 ft.

Wilson’s experience as an abalone diver combined with his training from E.R. Cross was a combination that positioned him and other Santa Barbara divers very uniquely. Abalone divers possessed three very important traits:

1. They were resourceful and understood diving, rigging, and marine equipment.

2. They were used to working long hours at sea in harsh conditions.

3. They understood that diving was just a means to get to a worksite and get a job done to turn a profit.

Wilson decided to carry out a demonstration dive using established U.S. Navy Diving procedures with oxy-helium to introduce mixed gas to the commercial world. He theorized that by doing a deep demonstration dive, he could convince oil companies that work could be done at deeper depths with longer bottom times to meet the needs of deepwater exploration.

Helmet Modifications

For helium mixed gas diving, the U.S. Navy had modified their Mark V air helmet into a bulky 250-pound-or-more apparatus. A recirculating canister, using a venturi principle, was incorporated to save on the expense of helium, rather than waste each breath by exhaling it back into the water.

[Ed.note: The gas was ‘scrubbed’ in the helmet to remove the CO2 and recirculated.]

The huge helmet needed to be lifted by a padeye on the top of the helmet in order to dress a diver. The helmet had been used successfully in 1939 during the salvage of the submarine USS Squalus off New Hampshire. The Navy Mark V helium recirculator helmet was largely viewed as impractical for use in commercial work. It was a challenge that Wilson had to overcome.

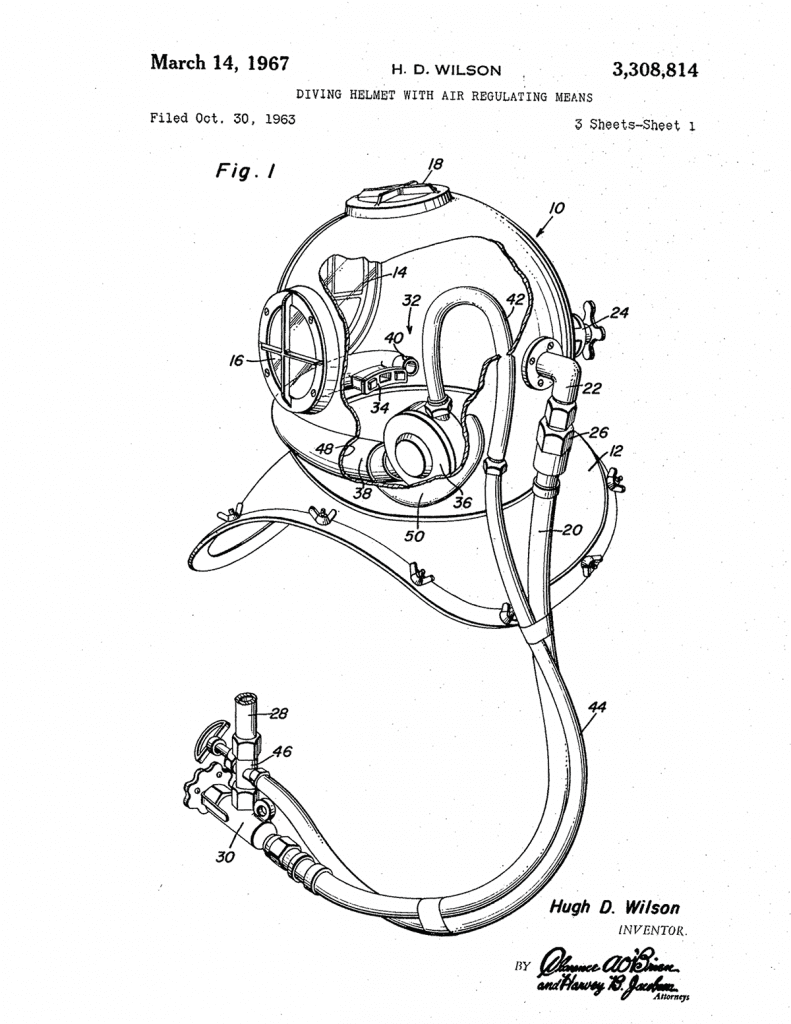

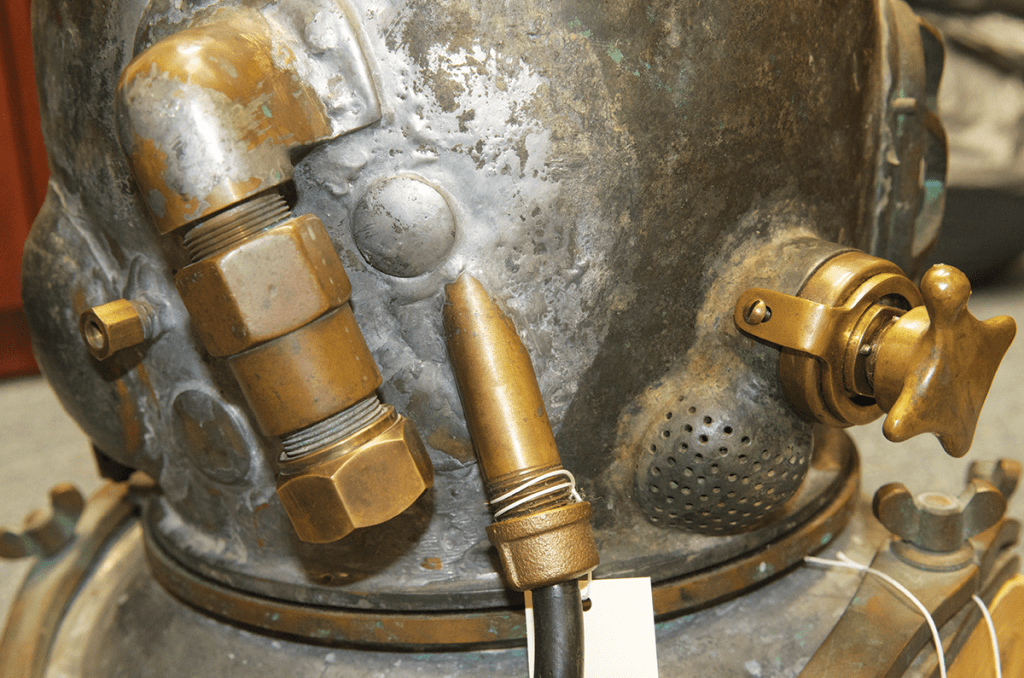

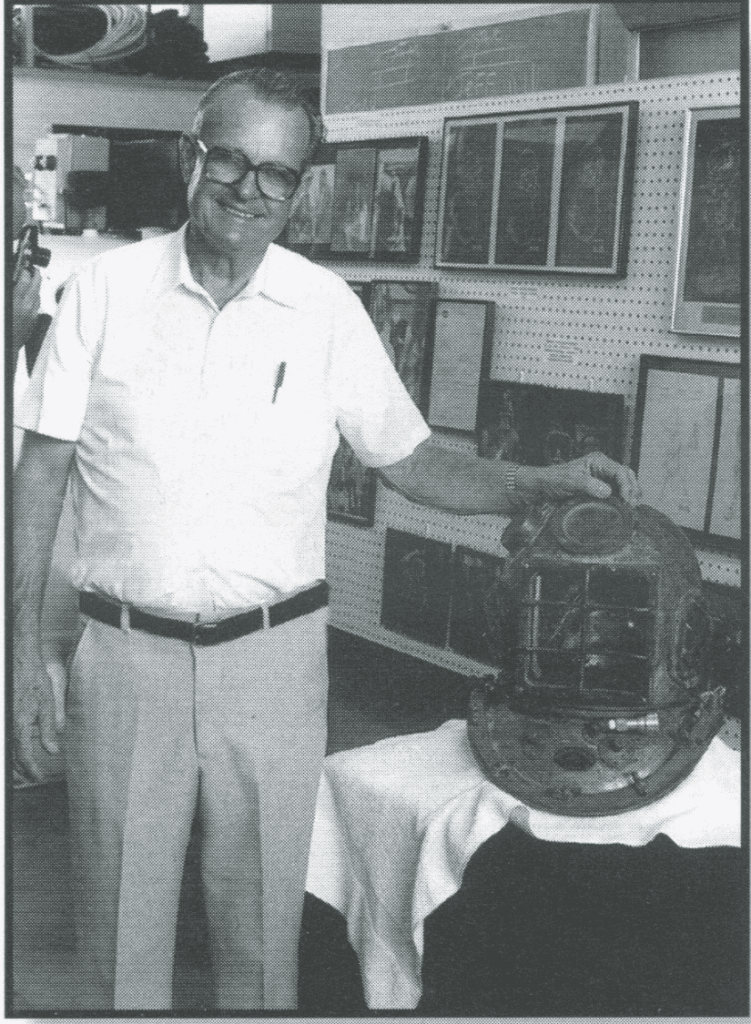

Thinking outside the box, Wilson modified his open circuit, air free-flow abalone helmet into an open circuit demand/free flow system fed with oxy-helium for the demonstration dive. [Ed.note: Rather than free-flowing into the helmet, Wilson added a second stage demand valve in the helmet to conserve gas.] This concept became the forerunner to the open circuit demand/free flow helmets used today. Wilson later filed for patent no. 3,308,814 for the modification on October 30, 1963.

Wilson knew that a successful demonstration dive would bring a competitive advantage over the domineering and elite Associated Divers. He was determined that an abalone diver could indeed break into this deep water market.

Wilson had the Santa Barbara Radiator Shop complete the modifications to his Japanese abalone helmet. They soldered a convex recess and an additional fitting on the left rear side of his helmet to accept one of the newly introduced single-hose, second stage regulators inside the hat. A Sportsways Hydronaut single-hose SCUBA regulator allowed breathing the heliox mixture on demand.

He mounted the first stage regulator to the standard Navy Mark V air control belly valve and fed it with a mixture of oxygen and helium stored in surface high-pressure cylinders. This provided a constant over-bottom pressure of 125 pounds per square inch (psi) or 8.6 bar, to the second stage demand mouthpiece, negating the need to “track” the diver with a topside regulator. The open-circuit demand/free-flow concept and design were both simple and effective, just what was needed for the rigors of commercial diving.

Bev Morgan was later hired by Wilson to build lightweight masks prior to his partnership with Bob Kirby [Bev Morgan went on to become the CEO of Kirby Morgan, which makes commercial diving gear]. He chuckled as he reflected on he and Ramsay Parks, returning to Santa Barbara after an abalone trip, seeing Wilson at a restaurant sometime prior to his record dive. At the time, Wilson was in the midst of working on his helmet modifications.

“We saw Danny’s station wagon in the parking lot and in the back he had his square ported abalone helmet and a bunch of scuba regulators. Ramsay and I looked at it and saw the modification bubble and figured out what he was up to. We had heard some harbor rumors that he was going to do some kind of gas dive. We went in and sat down at his table. It was like old-home week as we chatted,” Morgan said. “I decided to play a joke on him and told him that Ramsay and I were working on a helmet for gas diving using scuba regulators. His face became pale and he said ‘I gotta go!’ He ran out and came back in and that’s when I laughed and told him he should cover up his gear. On our way out, we saw that he had put a blanket over it all.”

The Big Dive

Loaded with flasks of oxy-helium, the 55-foot vessel Rio Janeiro left Santa Barbara early in the morning of November 3, 1962. Wilson used a small crew of divers and hands to assist and witness his attempt to prove a point. His tender was Jerry Ruse, who had worked with Wilson diving for abalone.

Wilson’s crew consisted of his eventual business partner, Ken Elmes, owner of the Santa Barbara harbor fuel dock, local fisherman Glenn Miller to skipper the boat, cave diver Jim Houtz, a photographer from Brooks Institute of Photography, and Ruse. He also had several safety divers using scuba to monitor him on his in-water decompression stops.

Also on board were Reggie Richardson, Warren Whitney, and Wilson’s wife Dorothy, who worked with Wilson at his abalone shop as an up-trimmer.

Wilson did not publicize the dive in order to avoid drawing attention from competing local divers. When they later heard of the dive, it was thought to be ludicrous, as he did not use a deck decompression chamber and worked from a boat that was nothing more than a fishing vessel.

Ruse, like Wilson, was an abalone diver. Wilson referred to the stocky former Marine as “Super Muscles.” Ruse told how the safety divers surveyed the area for current and sharks after dropping anchor. The water was green and murky but calm enough to conduct the dive.

Wilson made the dive using a standard U.S. Navy Mark V canvas dress mated to his newly modified Japanese abalone helmet. He used breastplate weights, as he did diving abalone. He wore brass weighted Navy shoes, and the standard Navy belly valve modified with the Sportsways first stage regulator connected to his gas supply.

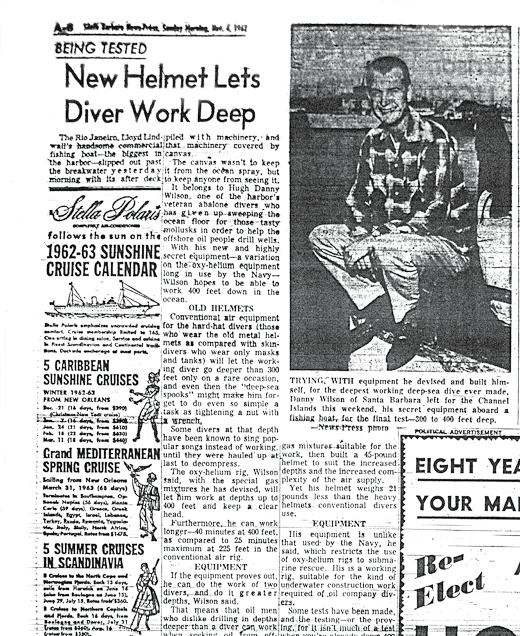

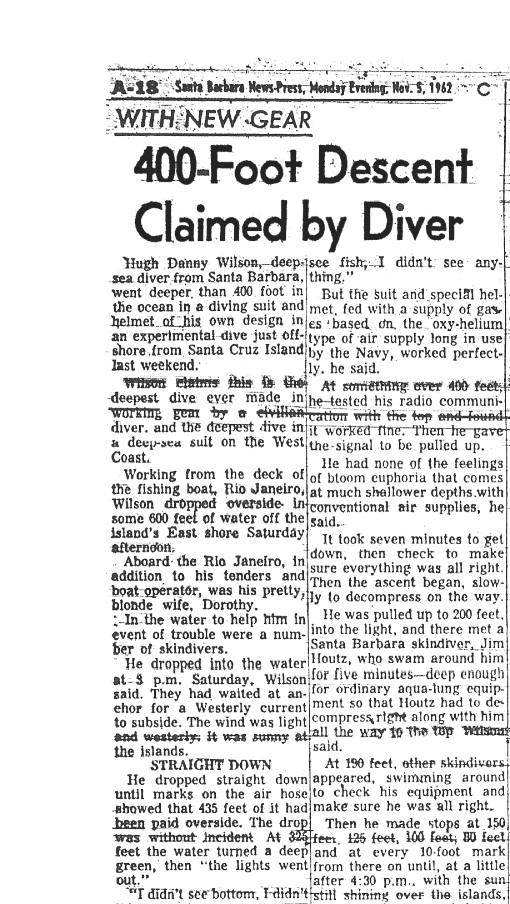

The Santa Barbara News-Press ran several articles on Wilson’s secret experimental dives off the southside of Santa Cruz Island. “On Wednesday (Oct. 31, 1962) Wilson took the Rio Janeiro to sea, anchored at 24m/80 ft, and went down the first time. On Thursday, he anchored farther out and dove to 61m/200 feet. Yesterday (Nov. 3, 1962) the Rio Janeiro left for the Channel Islands seeking a quiet place with a depth of 300 to 400 feet (92-123m) for the last and final ‘test’ of this new equipment” (Santa Barbara News-Press, 1962, A-6).

Wilson indeed dove to 123 m/400 ft, as was reported November 5, 1962, by the Santa Barbara News-Press. “He dropped straight down until the marks on the air hose showed that 435 feet of it had been paid over-side. The drop was without incident.” According to Wilson, “I didn’t see bottom, I didn’t see fish, I didn’t see anything.”

He made the dive using 80% helium, 20% oxygen for descent, and a bottom mix of 90% helium and 10% oxygen. He decompressed according to the U.S. Navy’s Helium-Oxygen Tables (See Dive Deeper below) for a 126m/410 ft completing all in-water decompression, and shifting to 100% oxygen at 15 m/50 ft.

Wilson left the surface at 3 p.m. and was back on the ladder at 4:30 p.m. During the decompression stops, Ruse recalled that the rigging on his breastplate weights almost slipped off. The safety divers quickly reattached the weights using some small fishing line, preventing a catastrophic “blow-up” in heavy gear that almost certainly would have resulted in explosive decompression sickness. He also mentioned that Wilson was constantly concerned with sharks in the area from his many encounters with them while abalone diving.

The first decompression stop on the Navy’s tables was at 52 m/170 ft for seven minutes. The second stop was at 37 m/120 ft for two minutes. The remaining stops were in 3 m/10 ft increments, and of several minutes in duration. At 15 m/50 ft Wilson was shifted to oxygen, the last water stop being at 12 m/40 ft.

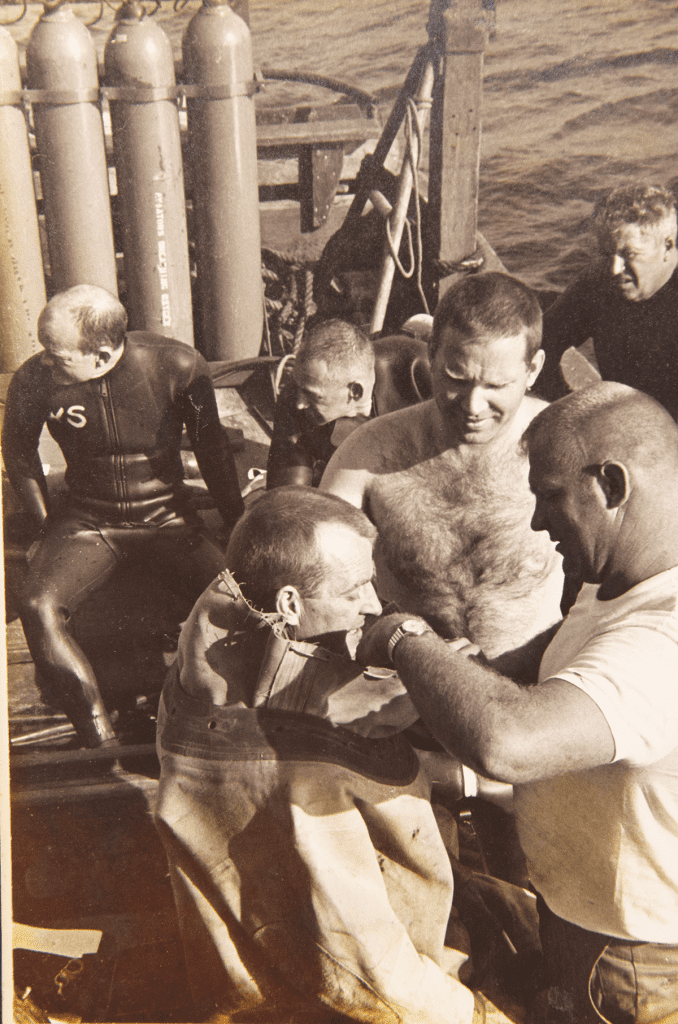

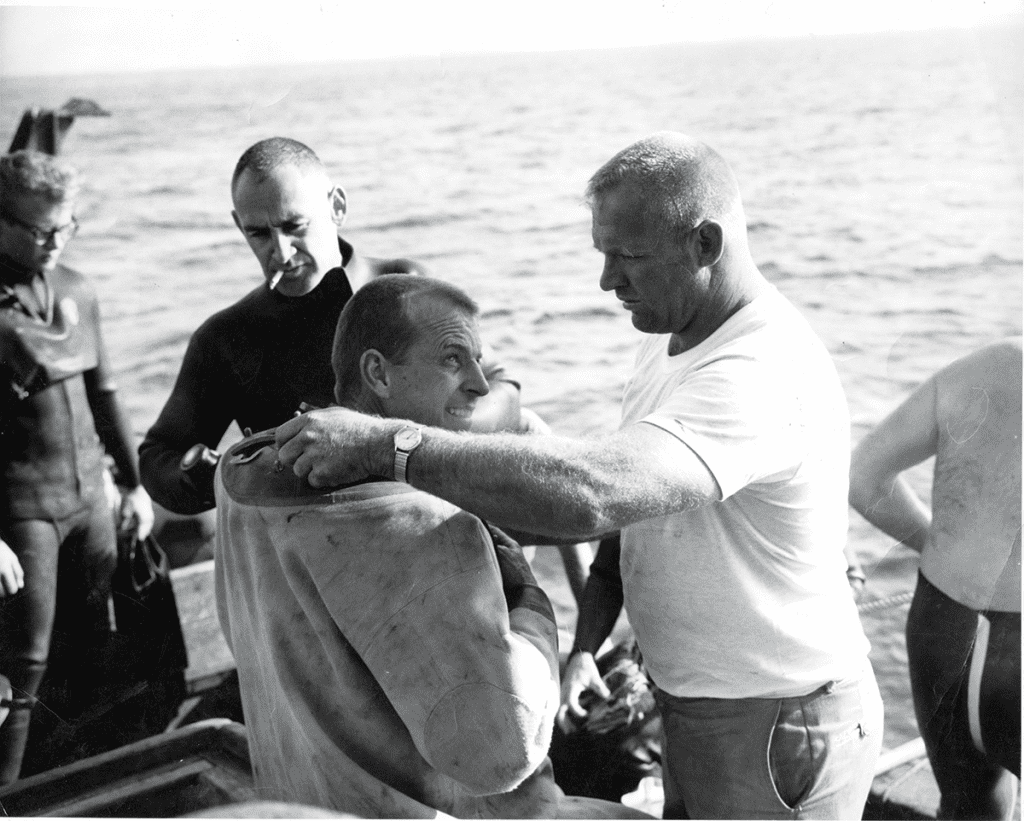

Once back on the surface, the helmet could not be disconnected from the breastplate. The leather gasket had swollen with water from the 200 psi plus ambient pressure. This swollen gasket wedged the helmet’s interrupted threads to the breastplate. The tenders had to unbolt Wilson’s breastplate and helmet from the suit.

When asked about Dorothy’s demeanor during the risky dive, Ruse responded: “She was pretty calm during the dive and rightly a bit nervous. When we could not get the helmet off she became quite upset though.”

Ruse and Houtz removed the wing nuts and brales from the dress and breastplate and lifted the entire assembly from the dress as one piece. A published photo from just after the dive shows Wilson standing on the dive ladder of the Rio Janiero after the helmet was removed, as was customary for abalone heavy gear divers.

By today’s commercial standards for gas diving, the dive was conducted haphazardly from nothing more than a 55-foot fishing vessel. He took minimal mitigation measures to offset the risks. There was no deck decompression chamber and Wilson shifted to in-water oxygen at 15 m/50 ft (PO2=2.5 atm)per the U.S. Navy protocol at the time. This was of great concern to Wilson, as he knew the hazards of acute central nervous system oxygen toxicity from his training at Sparling.

The dive was also made without the use of a pneumo-fathometer or kluge. According to Ruse, “ We had no way of knowing his exact depth as we had no kluge, but I personally taped up his hose and it was beyond 450 feet. We measured it afterwards out on the breakwater.”

Back in the Santa Barbara Harbor, word soon spread of Wilson’s dive using oxy-helium in order to break the lock on oilfield diving held by Associated Divers. Bob Kirby reflected on the attitude of Associated Diver’s Bob Rude toward helium diving: “We will come and recover Danny’s body from the bottom after he kills himself.” This of course only made Wilson even more determined to succeed in bringing mixed gas diving to the oil companies.

According to Ruse, Wilson had promised the oil companies that he could conduct dives with 60-minute bottom times and a clear head, versus the 25-minutes on air in a narcosis-induced stupor offered by Associated Divers.

The Birth Of Deep Water Commercial Diving

The historical significance of Dan Wilson’s 123 m/400 ft dive in November of 1962 is understated by comparison with Hannes Keller’s 306 m/1000 ft bell dive a month later. Keller’s dive ended in tragedy, while Wilson’s dive inspired the expansion of several industries resulting in a significant and lasting economic impact.

After the 123 m/400 ft dive, Santa Barbara diving pioneer Bob Christensen recalled, “He was almost immediately given a contract, trained a few divers rather rudimentarily and began using mixed gas.” Just over a month later, Wilson’s success with this demonstration dive using helium landed him a work order to put helium equipment onboard the Cuss I (Continental Union Shell and Superior) drillship working for Phillips Petroleum off Santa Barbara.

Thus came about the entrance of oxy-helium diving into the commercial diving arena, followed by the formation of General Offshore Divers, made up of Hugh “Dan” Wilson, Ken Elmes, and local abalone divers Lad Handelman and Whitey Stefens to do the gas work. Later, they were joined by Reggie Richardson as an additional investor.

Stefens, like Wilson, was an abalone diver who had also trained at E.R. Cross’s Sparling School of Deep Sea Diving and was familiar with the complexity and benefits of using mixed gas. “With a helium diver, you could talk to him and change his plan on the bottom. With an air diver at 250 feet, it’s very difficult, unless he’s very proficient,” Stefens explained.

“Danny taught us all how to go down and come up, and Whitey and I showed him how to get the work done,” recalled Handelman at Wilson’s memorial service in 2007. Reflecting on both Wilson and Stefens, Handelman said, “Each one of those guys had major ideas on how to do things, which forged a successful combination. I learned from both of them.”

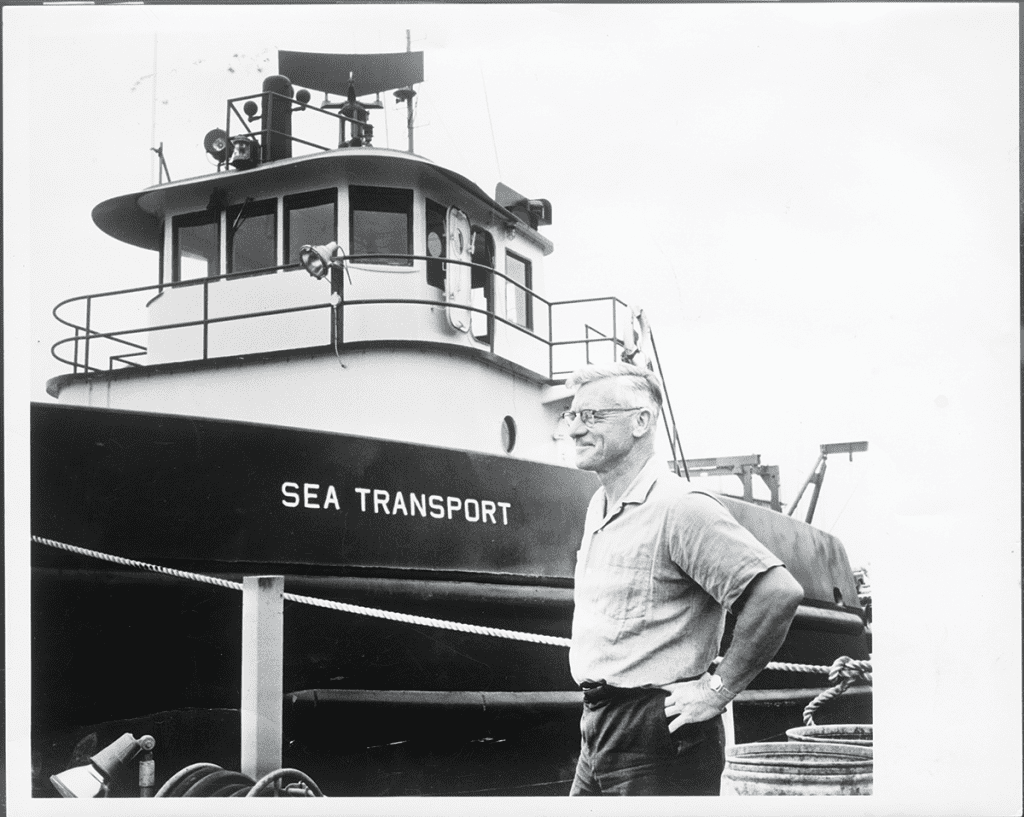

As Stefens explained about the company, “Kenny Elmes was our partner. He owned the fuel dock in Santa Barbara Harbor as well as General Offshore Transport, which was a fleet of vessels. Laddie and I each put in $10,000. Kenny put in $10,000, and then he had to put Danny’s $10,000 in, because,” he added with a chuckle, “Danny didn’t have it.” “He lived fast and whatever he made, he spent. But he made a fortune.” According to Handelman, “Kenny was the father of the whole thing. He was the brains behind the whole operation and had good business sense.”

With the introduction of mixed gas diving into the private sector, Associated Divers was rendered obsolete for deep water diving. The David of diving had slain Goliath, as the eventual demise of Associated Divers had begun. Although Associated Divers hired Bob Kirby to design and develop a competing gas re-circulating helmet, they had essentially “missed the boat.”

Many of the experienced divers with Associated Divers left to venture out on their own into helium diving to compete with Wilson. Murray Black and Woody Treen were among the Associated Divers who quickly made the transition into gas diving. Wilson and General Offshore recognized that helium had trade-offs with air diving. They also knew that their competitive advantage would not last long.

Both Stefens and Handelman later went on to become icons in the formation of several commercial diving companies over the years. They still reside in Santa Barbara and remain close friends. The success of General Offshore Divers in introducing helium for deep diving in the expanding local commercial diving industry soon saw them garnering nearly 60% of the work in the Santa Barbara Channel, all previously belonging to Associated Divers.

General Offshore began to experiment with adding nitrogen to the oxy-helium mix (i.e., Trimix) to combat the chilling effects of helium, as well as the voice changes that occurred. All of this required new and experimental decompression procedures which Wilson, Stefens, and Handelman developed and tested in a recompression chamber at Wilson’s abalone shop on Gutierrez Street in Santa Barbara.

By 1963, Wilson and General Offshore divers had successfully completed in excess of 300 dives using either oxy-helium or trimix as a breathing gas. They had logged more bottom time in the 77 m/250 ft range than had the U.S. Navy, including the salvage of the USS Squalus. (Journal of Diving History, Spring 2008 volume 16 issue 2 number 55,13). A shift in deep diving had begun from the U.S. Navy to the private sector commercial industry.

Just a year later, in November 1963, General Offshore began negotiations with General Precision Equipment and Union Carbide to sell the company. Free from the depth working constraints of narcosis, more productive and complicated work could ensue with oxy-helium as a breathing gas. Gas diving did, however, present even more challenges due to the cold and harsh elements of deep water. The divers needed protection.

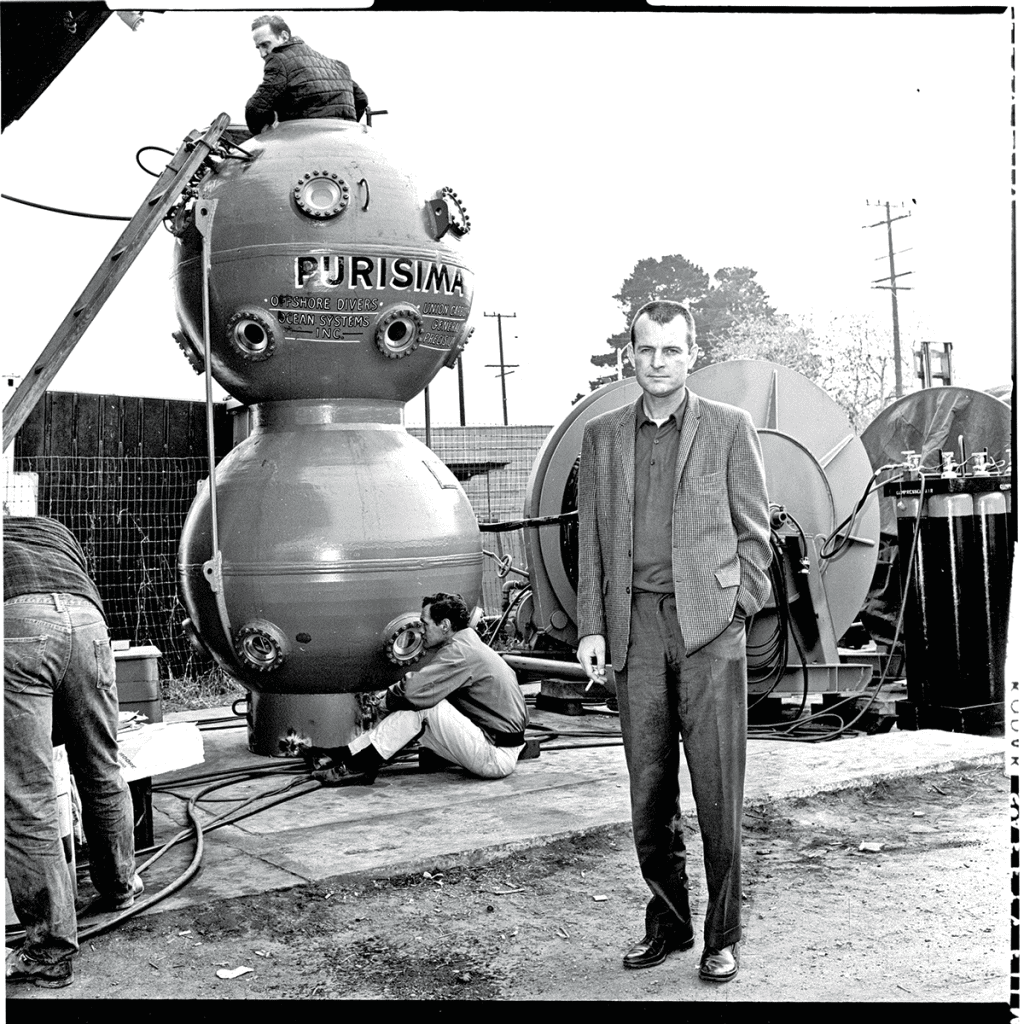

Wilson had previously conceived the design of a dual sphere diving bell, which could handle the pressure at 306 m/1000 ft, while abalone diving off Purisima Point in Santa Barbara County. The bell would protect the diver from the elements and allow oilfield engineers to observe dives at depth in the dry upper sphere, under one atmosphere of pressure. Additionally, the divers could complete the long hours of decompression in the comfort of the dry lower sphere of the bell.

The Purisima Lock-Out Bell

In 1964, Wilson and General Offshore built and launched Purisima, the world’s first commercial lockout bell, in Santa Barbara Harbor. While the concept of Purisima was advantageous, its initial use revealed many flaws and challenges that needed to be addressed. The bell was unstable in the water column, requiring the addition of a third sphere for buoyancy to keep it vertical. This made launch and recovery difficult in any kind of sea condition.

In addition, the diver hatch was undersized and a diver using heavy-gear could not exit very easily. Wilson hired divers Bev Morgan, Bob Ratcliffe, and Bob Christensen amongst others, and tasked them with building modified abalone masks for use with Aquala drysuits in Purisima bell lockout dives. This began the development of workable lightweight diving gear.

Later in 1964, General Offshore Divers finalized their sale to Union Carbide, Inc., and Oceans Systems, Inc. was formed, with Wilson and Stefens running operations as part owners. Purisima became a test chamber for experimental dives at Union Carbide’s research facility. The foundation of Ocean Systems, Inc. brought the world’s first industrial diving company into being.

Lad Handelman opted out in order to venture on his own, forming California Divers (Cal Dive) in 1965, with an office on Santa Barbara’s Stearns Wharf. California Divers was formed by brothers Lad and Gene Handelman along with fellow abalone and General Offshore divers Bob Ratcliffe and Kevin Lengyel.

Ratcliffe ultimately became Cal Dive’s equipment designer. He later designed and built a successful new fiberglass lightweight helmet called the “Rat Hat.” Cal Dive eventually merged with Phil Nuytten’s Can Dive and Worldwide Divers of Morgan City, Louisiana to form Oceaneering International, the world’s largest diving company at that time. Ratcliffe’s Rat Hat later became a standard helmet used by Oceaneering divers.

A Commercial Diving Pioneer

Deepwater offshore oil exploration was at a tipping point in the early 1960s. Wilson’s dive and his introduction of oxy-helium diving was the first domino to fall. While others were certainly aware of using mixed gas for deep diving, Wilson, Handelman, Stefens, and Elmes, along with the newly formed General Offshore Divers, were the first to act and put it to use for commercial purposes.

The result of this domino effect was significant. Competing local companies quickly emerged to use helium for deep diving. Newer equipment was developed to conduct deep diving operations, such as mixed-gas manifolds, diving bells, and lightweight swim-gear for exit out of bells. A massive worldwide labor demand was created to support all of the new offshore exploration that could now take place. Many of the copper-collar abalone divers soon became white-collar businessmen. A spirit of entrepreneurism emerged from the kelp beds of Santa Barbara that spread internationally in a new market-driven underwater economy.

Santa Barbara diving historian Chris Swann summarized Wilson’s legacy: “Dan Wilson saw an opportunity out here. He opened the door. He found a reasonable and practical way to dive with helium, and that was the beginning of the use of helium in the commercial diving world. He also took the next step, which was to develop the world’s first commercial lockout bell. You could say that someone else would have done both of those things. Quite true, but he was the first.”

To say that Dan Wilson was a pioneering force in commercial diving would indeed be an understatement. Wilson went on to start Subsea International in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico. Helium diving expanded globally in the U.K. North Sea and other international areas to support offshore oil development.

In 1968, he and others helped form the Marine Diving Technology Program at Santa Barbara City College. It was the first publicly funded commercial diving program to train marine technicians to support the explosive labor demand created by “The Santa Barbara Helium Rush”. He influenced and inspired many to follow his creativity, taking big risks with potential for big rewards.

Wilson retired from diving before the age of 50 to sail the world with his beloved wife, Dorothy. He died in 2007 at age 78 after a lengthy illness. Wilson and the diving pioneers of Santa Barbara paved the road for those of us who followed years behind them. Equally as important, they researched and developed techniques and equipment to improve safety and advance the industry of commercial diving.

Reprinted from The Journal of Diving History Fall 2012 Vol. 20, Issue 4, #73

Dive Deeper:

US Navy Experimental Diving Unit: HeO2 Decompression Tables (September, 1950)

US Navy Experimental Diving Unit: Computing Helium-Oxygen Decompression Tables (September, 1950)

aquaCORPS 1994 tek.Conference Talk: “The Early Days of Helium Diving” Dan Wilson and Lad Handelman discuss their company’s transition to helium diving at the 1994 tek.Conference.

aquaCORPS # 5 BENT (1993) Making The Grade: Interview With Commercial Mixed Gas Pioneer Lad Handelman

References

Davis, S. H. (1935). Deep Diving and Submarine Operations (9th ed.). Cwmbran, Gwent, UK: Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd.

Kirby, B. (2002). Hard Hat Divers Wear Dresses. Los Olivos, CA: Olive Press Publications.

Kirby, B. & Leaney, L. (1999, Summer). Development of the Kirby Helium Re-circulator Helmet. Historical Diver, (20), 17-25.

Kirby, B. Morgan, B. & Leaney, L. (2002, Summer). A History of Kirby Morgan Diving Equipment. Historical Diver, 10(3), 26-39.

Lundy, A. L. (1997). The California Abalone Industry: A Pictorial History (1st ed.). Flagstaff, AZ: Best Publishing.

NAVY Dept. (1958). U.S. Navy Diving Manual. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Parker, T. R. (1997). 20,000 Jobs under the sea- a history of diving and subsea engineering. Palos Verdes Peninsula, CA: Sub-Sea Archives.

Santa Barbara News Press (1962, November 5). 400 Foot De-scent Claimed by Diver. Santa Barbara News Press, A-18.

Santa Barbara News Press (1962, November, 4). New Helmet Lets Diver Work Deep. Santa Barbara News Press, A-6.

Santa Barbara News Press (2007, September 2007). Obituaries: Wilson, Hugh “Dan”- Commercial Diving Pioneer. Santa Barbara News Press,

Swann, C. (2008, Spring). The Development of Commercial Helium Diving. Historical Diver, (55), 9-17

Swann, C. (2007). The History of Oilfield Diving: An Industrial Adventure. Santa Barbara, CA: Oceanaut Press.

Tillman, T. (2002, Fall). The Keller Dive Reviewed. Historical Diver, 10(4), 34.

Zinkowski, N. B. (1971). Commercial Oilfield Diving (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MD: Cornell Maritime Press, Inc.

Don Barthelmess has been involved in professional diving for over forty years as a diver and educator. He helped launch, develop and advance many marine careers. He began working in commercial diving as a diver, submarine pilot and ROV technician for International Underwater Contractors, Inc. Don served as General Manager of their Pacific division in Ventura, CA. In 1982, he set a depth record diving to 1,972 fsw operating an atmospheric diving system in the Gulf of Mexico. A tenured Professor for thirty years at Santa Barbara City College, he trained divers in the renowned Marine Technology Program. Don shaped attitudes, sharing his philosophy of safety and teamwork through hands-on training in realistic experiences.

A contributor and reviewer for the NOAA Diving and Commercial Diver Training Manuals, Don built upon a trainee’s foundation of SCUBA while introducing advanced modes of diving to match specific underwater tasks. He holds degrees from Florida Institute of Technology in Underwater Technology and California State University in Occupational Studies. His graduate degree is in Educational Technology from Pepperdine University. Don was recognized as Santa Barbara City College’s 29thFaculty Lecturer, the College’s highest honor. He was selected as the 2020 NOGI recipient in Sports & Education by the Academy of Underwater Arts & Sciences (AUAS).

An avid volunteer, he served for twenty-five years with The Association of Commercial Diving Educators co-authoring the American National Training Standard for Commercial Divers. As President of the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum and past President of the Historical Diving Society USA, he embraces the past to guide our future.

Be a Part of Diving History!

The Historical Diving Society USA is a non-profit organization dedicated to serving the dive community by:

• Researching, archiving and promoting great moments in dive history.

• Honoring the contributions of underwater pioneers.

• Facilitating access to the rich history of diving on various platforms.

• Enhancing awareness of and appreciation for underwater exploration.

To access our treasure trove of dive history and become a member, visit us at: www.HDS.org. We are also on Facebook: Historical Diving Society USA