Community

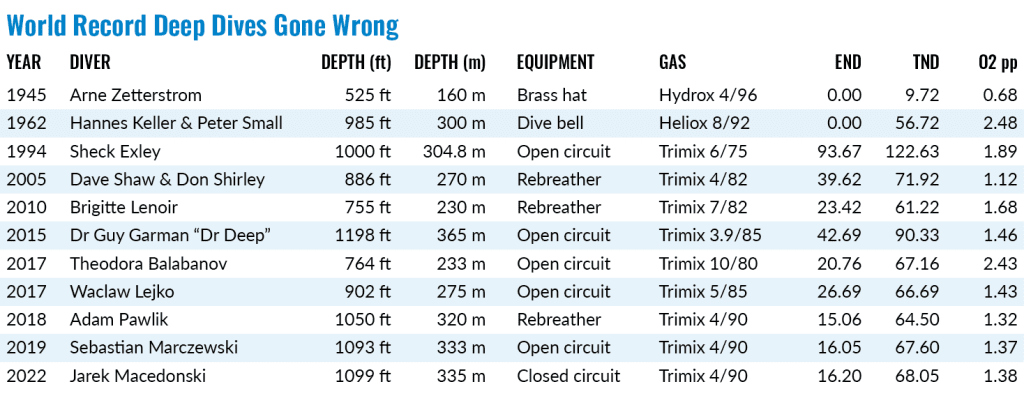

The Risk and Management of Record Chasing

The pursuit of deep diving records is an unsettling but accepted facet of tech diving culture. On the one hand, we are driven as a species by our genetic predisposition to “Go Where No One Has Gone Before.” Blame it on our DRD4-7R explorer gene! On the other, many question the value and legitimacy of conducting a high risk, touch-and-go line dive for recognition and bragging rights alone. Where and how do we reconcile the two? Here diving physiologist Neal Pollock seeks to answer those questions in a compelling, principled exposition that may help you to sharpen your beliefs.

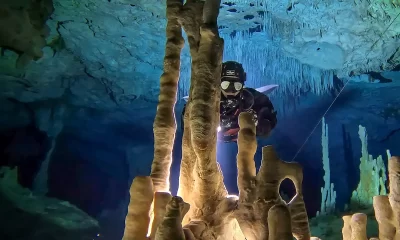

By Neal W. Pollock, PhD. Header image: Nuno Gomes getting ready to make his 2005 world record dive to 318.25m m/1039 ft in the Gulf of Aquaba.

Humans have probably been chasing records as long as we have existed. Og was almost certainly proud of discovering that two stones could be rubbed together to make fire, and it likely resulted in a solid community standing for at least a while. Tempting though it may be, we cannot blame our interest in records on the advent of the Internet or social media. The Guinness Book of World Records, a small example of documenting novelty, was first published in Great Britain in 1955. The Internet and social media, however, have made the striving for and tracking of new records more intense.

Record making is well established in diving as well as in most other communities. There are interminable lists of the first makers of equipment, the first to implement or explore, and the most extreme doers of deeds. History shows them to be pivotal, meaningful, or trivial as it unfolds. Keeping the record straight is important, but the decision as to why and whether to pursue records is worth debating.

I am a fan of documenting meaningful events, but I have concerns over an excessive focus on arbitrary milestones. When a community puts more weight on records than actual achievements, the drive can become pointless or problematic. The pointless includes many Guinness records, such as the most number of people brushing their teeth simultaneously and the largest rubber band ball.

While some in the diving community have pursued fairly pointless but low risk records, it is the problematic ones that are a much greater concern. Underwater activities involve greater risk than many other endeavors, relying on equipment, training, technique, and practice to produce an envelope in which reasonable levels of safety can be maintained. Pursuing records is generally about pushing boundaries, and when the boundaries are set by the interaction of physics and physiology, the erosion of safety buffers can produce serious risk. The pursuit of targets can overwhelm well-founded safety concerns and common sense.

“Record chasing can produce good outcomes, and some meaningful achievements, but when going forward is reliant on misplaced beliefs that personal motivation and superiority can overcome unforgiving limits, the outcome can be bad for both individual and community, even if considered successful.”

Record chasing can produce good outcomes, and some meaningful achievements, but when going forward is reliant on misplaced beliefs that personal motivation and superiority can overcome unforgiving limits, the outcome can be bad for both individual and community, even if considered successful.

One of the chief challenges in diving is that the interaction of physics and physiology creates difficult-to-define limits. There are differences in tolerance between individuals and often between exposures. Different breathing gas mixtures can alter narcotic potential, respiratory gas density, decompression stress, and susceptibility to oxygen toxicity and high pressure nervous syndrome, among other concerns. Differences in workload, stress, physical fitness, and physical skill can also alter the response to other more fixed stressors. Practically, the interactions between the host of factors is complex and can make the element of chance more important than people would like to admit. A scary reality of many boundary-pushing events is the fact that getting away with something once, or even multiple times, does not necessarily make it safe, and almost certainly not safe for all.

Records achieved with a large helping of good luck still count, but they can be extremely troubling if others are encouraged to try to surpass them. Not only can tolerance and good fortune differ, the lessons learned in building to “record” performance may not be appreciated by those who follow, potentially magnifying the risks.

Care is warranted to decide on what “records” are truly worth pursuing and what should be left alone. A simple practical test is whether an activity serves any purpose beyond the record attempt. If there is no other benefit or purpose, the value in it may not be sufficient to continue, especially when the associated risks may be high.

Record attempts are sometimes pursued by relative newcomers to a field. It is unclear how much of this is due to simple enthusiasm or a desire to stand out, but all such efforts are best met with counsel before encouragement. The field needs leaders, and the next generation of leaders, but this requires keeping those with potential both healthy and engaged. This may come down to mindset—finding what is most important and appropriate to pursue as part of personal growth.

Leaders who want to establish themselves are best served by ensuring that they have the best understanding, skill, and experience within the realm of what they will need to do rather than pushing the envelope for increased fame. Chasing records by sacrificing safety margins and/or ignoring compromised states of affairs is not compatible with accepted best practice. Those looking up to leaders for inspiration may not fully appreciate the issues and concerns, but the best leaders will be conscious of the total impact their efforts can have on others.

Bragging about exceptional or record exploits is problematic in that it can encourage others who may be inadequately prepared to follow suit. It may be a hard reality for the keen, hungry, and superbly confident instructor to accept, but they can provide a much better service to their students by encouraging them to stay within the accepted realm of operational safety. This is often most effectively demonstrated through example. The goal should be to promote a long and healthy diving life, effectively achieved by solid training and an instilled appreciation for the value of robust safety buffers and a constant revisiting of “what if” preparation.

We should recognize the meaningful efforts in the community, but without losing sight of the implications of such endeavors. Promotion of a positive safety culture requires questioning whether things should be done, and how things that should be done can be done with appropriate safety margins. If meaningful efforts result in record achievements they should be applauded, but always with an appropriate framing of any associated value, limitations, hazards, and implications.

Reporting the exceptional is important, but a high priority should also be put on recognizing activities and efforts that are unexceptional in outcome due to appropriate preparation and execution within safe boundaries. Efforts to improve training, awareness, and operational safety must always be promoted. Safety programming is challenging since, when it is effective…, nothing happens. Ongoing commitment is required to ensure that it continues to be effective.

I would posit that the best record attempts are those pursued without fanfare, moving quietly from concept through to safe workup stages and then safe completion. The reporting of record efforts should always consider the value and relevance of the activity. Achievements that violate the criteria for safe performance should be neither encouraged nor glorified.

We live in a time when the pursuit and promotion of records can be expected to continue, but appropriate framing can help to ensure that the community benefits from a sustained focus on safety and thoughtfulness.

See Companion Story: I Trained “Doc Deep” by Jon Kieren

Dive Deeper

InDEPTH: Fact or Fiction? Revisiting Guinness World Record Deepest Scuba Dive by Michael Menduno

InDEPTH: Karen van den Oever Continues to Push the Depth at Bushmansgat: Her New Record—246m by Nuno Gomes

InDEPTH: South African Cave Diver Karen van den Oever Sets New Women’s Deep Cave Diving Record by Nuno Gomes

InDEPTH: Opinion: Don’t Break That Record by Dimitris Fifis

InDEPTH: Diving Beyond 250 Meters: The Deepest Cave Dives Today Compared to the Nineties by Michael Menduno and Nuno Gomes

InDEPTH: Extending The Envelope Revisited: The 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives by Michael Menduno

InDEPTH: High Pressure Problems on Über-Deep Dives: Dealing with HPNS by Reilly Fogarty

Neal Pollock holds a Research Chair in Hyperbaric and Diving Medicine and is an Associate Professor in Kinesiology at Université Laval in Québec, Canada. He was previously Research Director at Divers Alert Network (DAN) in Durham, North Carolina. His academic training is in zoology, exercise physiology, and environmental physiology. His research interests focus on human health and safety in extreme environments.