News

The Review: I Live Underwater by Max Gene Nohl

By Jeffrey Bozanic. Special thanks to the Wisconsin Historical Society for their help with images.

For decades, I have wondered who, exactly, Max Nohl was. All I knew about him was that he had done a dive to 128 m/420 ft using a helium/oxygen breathing gas mix in 1937 and lived to tell the tale. How did he accomplish that? What equipment did he use? What was his background? Did he accomplish anything else of note? Who, exactly, was Max Nohl?

When I was offered an opportunity to read a pre-publication release of a manuscript written by Nohl, I jumped at the chance. I did not know what to expect, but I did want to learn more about his record-setting 1937 dive. What I found were a bunch of surprises—as well as many intersections with my own diving career.

The first chapter details how Nohl drowned in Moose Lake, Wisconsin, when he was a young boy. I immediately flashed back to the stories that my mom would tell of me being recovered from the bottom of swimming pools and occasionally necessitating artificial respiration—sometimes not. There were community pools, relatives’ pools, and swim school pools. It seems that I had an affinity for the water and believed (incorrectly) that I knew how to swim. The difference is that I was not old enough to remember those events. Nohl was. One might think that would deter someone from entering deep water again—not Nohl.

One of my most memorable scuba dives was on the Empire Mica in 1988. Located south of Panama City Beach in the Florida panhandle, it was torpedoed by a German U-boat during WWII. Nohl was diving there in 1944, just two years after it sank. His description of thousands of barracuda evoked memories of the thick schools of fish I encountered on the wreck. And his recital of his decompression was almost eerie in its similarity to what happened to me during my decompression stop. Both of us found ourselves hurtling through the water just a few feet below the surface holding onto our safety lines after the anchor lines securing our respective vessels to the wreck parted while we were still in the water.

I could have been in a time machine. I dove in Wakulla Spring 35 years after Nohl did, yet his description of the water was just as apt for my dives. However, Nohl’s freedom to dive in Wakulla Spring contrasted with the constraints I had while diving in the same location. I was jealous reading about the broad range of his activities there and the unique dive support structures that he placed to further his goals.

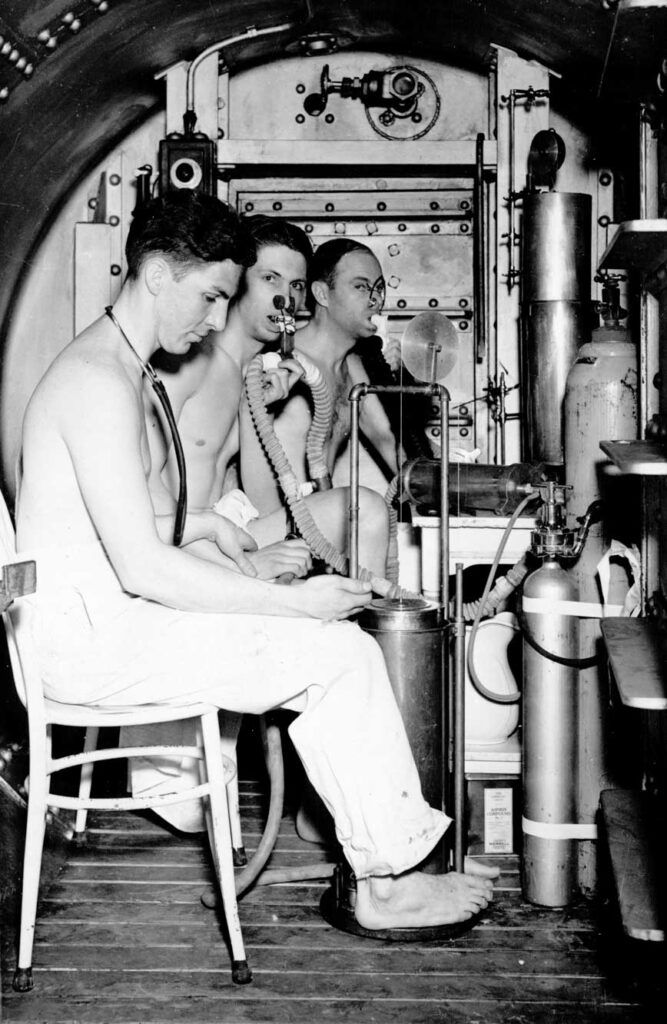

Inside the pressure chamber of the Milwaukee County Hospital, experimenting with helium. Dr. Edgar End at left, checking Nohl’s pulse. At right is John Craig. Photo courtesy of the Milwaukee Public Library.

The helmet used on Nohl’s first dive. Left to right: Max Nohl, Jack Browne, and Verne Netzow. Nohl wrote, “We later attempted to make this into a complete suit, patching together a pair of old overshoes and the rubber from several discarded inner tubes. Comparatively, a sieve is watertight.” Credit: Milwaukee Public Library.

Credit: Milwaukee Public Library

I am a co-inventor on several patents dealing with rebreathers; I have also written a textbook on the topic. I had no idea that Nohl designed and marketed a rebreather in the 1950s—nor did I know that his first patent, filed in 1939 when he was just 27, described a recirculating respirator that enabled him to descend to 420 ft in Lake Michigan. In addition to our similar interests, he also had problems equalizing on many of his dives, including his record-setting deep dive. I could completely see myself in his boots as he described the frustration and pain that he faced on some of his dives.

I was surprised to hear of the close friendship and business relationship that he had with Jack Browne. Browne and Nohl began Diving Equipment & Supply Company (DESCO) together. DESCO went on to become one of the largest equipment suppliers in the world for commercial divers. It was also curious to learn of his association with John Craig, another diving legend of whom I have read. (I read Craig’s book, Danger is My Business, dozens of years ago.)

Well beyond my experience, though, was his recounting of his participation in early research work in decompression sickness and saturation diving experiments. In addition, he designed and built a neutrally buoyant diving bell at about the same time that Barton and Beebe built and dove their bell off Bermuda to a depth of over 0.8 km/0.5 mi. Nohl was truly an amazing man and dive pioneer in many areas.

Unfortunately, Nohl was tragically killed along with his wife in a fatal car accident 1960. He had submitted the manuscript for this book to a literary agent a few weeks before his unfortunate accident and, since that time, it has been preserved in the Milwaukee Public Library’s (MPL) Local History Manuscript Collections (LHMC). Nohl’s manuscript will be published in May 2025 by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. All I can say is “Thank you!” for making this story available to us!

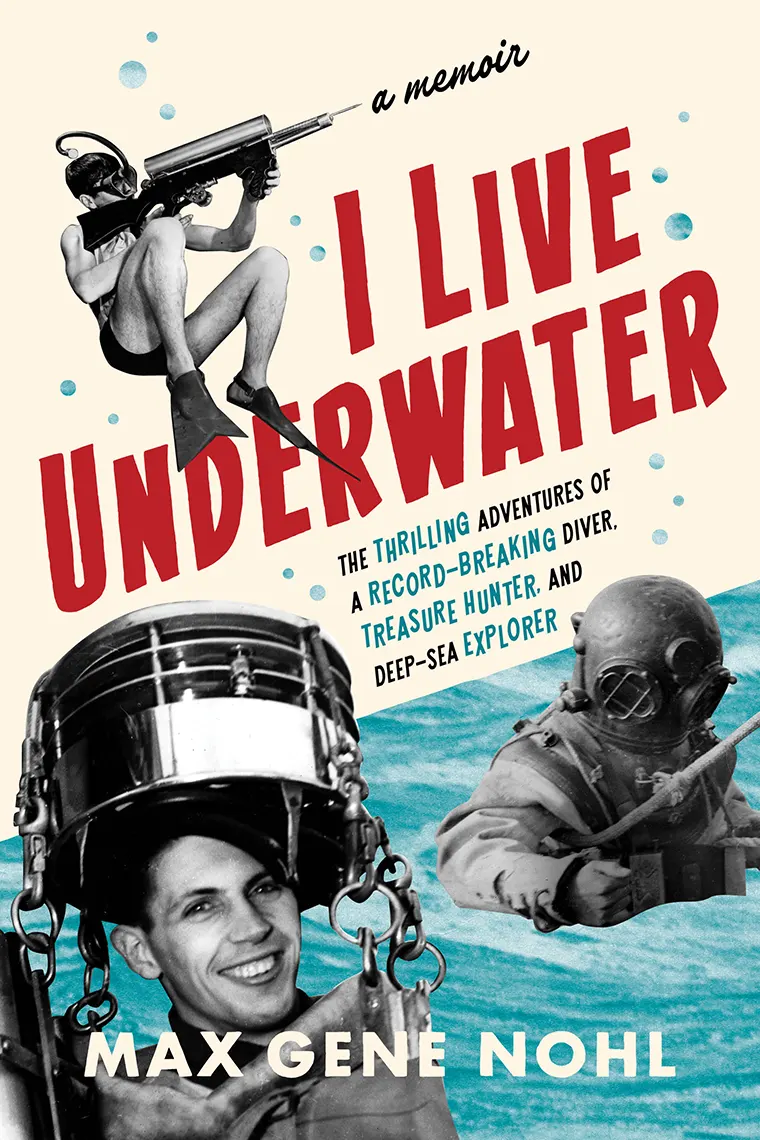

I Live Underwater: The Thrilling Adventures of a Record-Breaking Diver, Treasure Hunter, and Deep-Sea Explorer

Written by Max Gene Nohl

Paperback: $30.00 | 408 pages, 6 x 9 | ISBN: 978-1-9766-0028-9

E-Book: $15.99 | ISBN: 978-1-9766-0029-6

Publication Date: May 20, 2025

I Live Underwater is available from booksellers everywhere or at shop.wisconsinhistory.org. The book is also available as an e-book from all major e-book outlets.

DIVE DEEPER

USPO: Max Nohl Suit Patent #2,324,716

Wisconsinology: Max Nohl and the Underwater Necropolis

Wisconsin Historical Society: Max Nohl Underwater Films

Jeffrey Bozanic is a technical diving instructor and research scientist. Based in southern California, Jeff provides consulting and training services in the diving market. Specializing in rebreather use, he is probably best known for his seminal textbook on the topic, Mastering Rebreathers, and his work as senior Technical Editor for the 6th Edition of the NOAA Diving Manual. He has been honored with the NAUI Lifetime Achievement Award, DAN/Rolex Diver of the Year, AAUS Conrad Limbaugh Award for Scientific Diving Leadership, and the AUAS NOGI (Sports/Education). Contact: [email protected]