Community

The Mermaids of Weeki Wachee

InDepth editor Pat Jablonski takes us to see the longest running mermaid show on Earth that dates back to 1949, and discusses what it takes to be one of the park’s seventeen aquatic athletes. In addition to their shows, Weeki Wachee mermaids guard the site of deepest active cave exploration in North America.

By Pat Jablonski

All images by Nikki Webster, Brit on the Move, unless noted.

You could be forgiven for thinking how easy it must be, but if Linden Wolbert’s story about being a professional mermaid didn’t convince you that mermaids are aquatic athletes, you can’t be convinced. But never mind. As long as you enjoy the show, because after all, that’s what the mermaids want you to do. At Weeki Wachee, anyway.

Weeki Wachee Springs State Park, located near the west coast of north-central Florida, is a family-friendly water park that features—you guessed it—mermaids. Following its lock down during the pandemic, the park re-opened on Memorial Day. Since this issue of InDepth features mermaids, and since it’s a mere two hours south of High Springs (GUE’s home base), we sent a willing volunteer. Me.

So ordained by the Seminoles in Florida, Weeki Wachee means little spring or winding river, but the spring is anything but little. From its subterranean caverns, Weeki Wachee spews forth over 140 million gallons of clear, fresh, 23 °C/74 °F water daily. Divers have explored the springs to depths of 131 m/429 ft and surveyed more than 9.7 km/32000 ft, but the end has yet to be found. Are you curious yet?

First, you should know a little history about the mermaid show: A former navy man turned swim coach turned event promoter, Newt Perry, purchased Weeki Wachee Springs in 1949. At that time, it was full of trash and junk, all of which had to be cleared before he could fulfill his dream: producing an underwater mermaid show and sharing it with the public. He invented an underwater breathing apparatus—a free-flowing air hose supplying air from a compressor—and built an 18-seat theater. He would later build a 50-seater when viewing windows were added. He sought out pretty girls who could swim, and taught them to perform ballet moves underwater, and the mermaid shows of Florida were born.

In 1959, ABC TV bought the park and built the current theater that seats 400, but when Disney World opened just 161 km/100 miles to the east, yankee visitors flocked there. Weeki Wachee lost its tourist appeal, fell into disrepair, and changed hands several times, until the state of Florida purchased it and integrated it into the Florida Park Service. Florida probably got a heck of a deal. The mermaids became park rangers, and during the pandemic they spent a year practicing and choreographing routines.

Entrance fee for an all-day pass to all parts of the park is US$13 for adults, $8 for children aged six and above. Meandering toward the signs boasting the mermaid show, visitors will note how well-kept the grounds are. Once they arrive at the theater entrance, they will be greeted by a mermaid-out-of-water who is in charge of allowing patrons into one of the four half-hour shows every day, seven days a week.

The Show Must Go On

Waiting in line for the 1:30 show, “The Wonders of Weeki,” in which “the mermaids of Weeki Wachee showcase the history of the park and mermaid feats of yesteryear,” the greeter was Mermaid Brittany, who was happy to talk candidly about her experience as a Weeki Wachee mermaid. She’s an Ohio girl who loved the water, so she headed for Florida, where she settled and worked in a dive shop in Crystal River while becoming a master diver. When she saw a notice for mermaid tryouts, she applied, and out of 200 hopefuls, five were selected—Brittany among them. The tryout involved an endurance test, an underwater test with open eyes, and some ballet moves. Making the cut was only the first hurdle. Following her selection, she spent four-to-six months training before she was cleared to perform on the show. She’s been there three years now and wouldn’t change places with anyone on the planet.

In line were probably two or three hundred people. Outstanding among the excited patrons were some notable little girls wearing mermaid-themed clothing and clutching sequined mermaid dolls. Not a lot of boy children were to be seen, which brought to mind something Brittany said—men didn’t tend to apply when openings were available for princes. “They must not see it as manly,” she guessed. Could they be missing out?

After walking down the sloped steps of the newly refurbished, newly reopened, auditorium to get near the front and sitting down facing a curtained wall of glass in an air-conditioned auditorium, old videos of past mermaid shows played on multiple TV screens strategically placed around the room. The last of the videos were in color, and the montage ended with highlights from a 2012 Jimmy Buffet concert in the park.

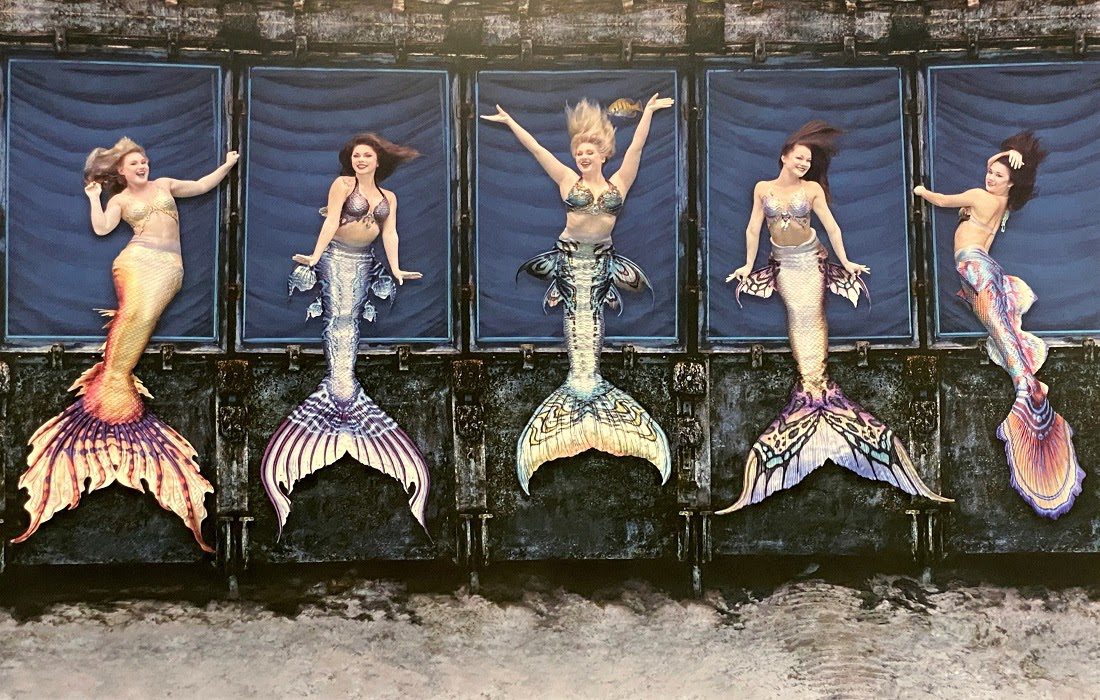

The theater darkened, and a porthole at the top of the stage opened up. A mistress of ceremonies popped her head out and let the audience know that they were in for a treat, that they were welcome to take photos—but warned against using a flash—and encouraged applause and cheering, as the mermaids could hear and would respond to encouragement. She called out, “Enjoy the Show,” closed the porthole, and disappeared, only to reappear as the curtain rose underwater flanked by two bejeweled mermaids. These three young women hovered in a perfect line underwater, smiling and waving as the story began.

Aquatic Athletes

There is no doubt that the glamorous mermaids are graceful aquatic athletes. They smile as they swim—dolphin style—and mouth the dialogue that is synced with the show so perfectly that the younger members of the audience could believe they’re speaking. Their need to take breaths is not nearly as obvious as one would think. They make it look that easy—which is their job, after all—but a dropped hose or hair entanglement in the hose can create problems—problems they solve with hardly a pause in the action. A fun fact: the mermaids at Weeki Wachee don’t actually breathe as a diver would from a regulator. Indeed, the air is forced into their lungs through the hose, one with a toggle that they control. They have to keep their lungs half-full in order to maintain neutral buoyancy. Also, when they are hovering in place—as they do, a lot—they are fighting a current, so they have to stay in a perfect line (think a line of chorus girls), as well as at the same depth. It’s synchronized swimming taken to a whole new level.

The shows are thirty minutes, in which time several costume changes take place, all underwater, out of view of the audience. Can you imagine changing from one elaborate costume to another underwater? Holy cow.

After the show, there is an opportunity for patrons to meet a mermaid and have photos taken with her as she sits upon her throne. This is one more obvious bit of proof that park visitors are in a state park rather than a for-profit entertainment venue: Take as many photos as you like, with each member of the family. Little girls beamed to be standing proudly next to a real, live mermaid as their parents and grandparents snapped away—all free of charge.

Sometimes the mermaids have to fend off the occasional inappropriate comment, but the hardest thing for Brittany was learning to not react to the terrible burning sensation of water up her nose. Think about it.

Becoming a mermaid at Weeki Wachee is not a career move for most. There are currently seventeen mermaids performing, and reportedly they are as “close as sisters.” When one leaves—as one did recently, for law school—they cheer her on. Some of the former mermaids—the “sirens”—return for reunion shows.

The New York Times ran an extensive piece about Weeki Wachee before Covid, back in 2013, “The Last Mermaid Show,” written by Virginia Sole-Smith. Virginia might be surprised to discover the renewed interest in mermaiding—it’s even a verb now.

Come on down and see for yourself.

Dive Deeper:

InDepth: Exploration of Weeki Wachee 2019-20: The Search for The Source Continues by Charlie Roberson

Alert Diver: “Where Mermaids Fear to Tread” by Michael Menduno

Pat Jablonski heads up the copy edit team for InDepth. She is a blogger, a writer of stories, a retired tutor, English writing teacher, and therapist. She’s a friend, a wife, a proud mother and grandmother. She is also a native of Florida, having spent most of her life in Palm Beach County. She has a B.A. in English from FAU in Boca Raton and an M.S.W. from Barry University in Miami. She learned to swim in the ocean, but she doesn’t dive.