Conservation

The Challenge for the Technical Diving Community? Connecting Divers With the Environment

By Alex Brylske, Ph.D. Header image: tech divers clearing ghost fishing nets courtesy of Ghost Diving International.

While tech diving has come a long way in terms of extending our underwater envelope, enabling tech divers to truly go where no one has gone before, environmental consultant and educator, Alex Brylske, Ph.D argues that as a community there is still room for significant improvement in connecting divers with the environment. In the process, he details the results and meaning of InDEPTH’s survey of Sustainability in the Scuba Diving Industry and offers suggestions for moving forward.

In the interest of full disclosure, I am not a technical diver. However, I do have great admiration for the contribution technical diving has made to recreational diving. The list of innovations from the tech world—and especially cave diving—adopted by those of us in the rec world is, indeed, impressive. That list includes contributions in the technology realm such as the buoyancy compensator, the alternate air source, the DSMB and enriched air. In the realm of practice, tech diving has contributed much to both gas management (“rule of thirds”) and enhanced decompression safety (deeper safety stops and improved decompression algorithms). Today, all forms of open circuit diving are safer because of the explorers who have dared to push the envelope while striving for ways to make the journey safer.

Yet, I believe there is one arena of the diving experience where there’s still room for significant improvement in both the tech and rec realm, and that’s connecting divers with the environment. It’s in everyone’s best interest, perhaps, to acknowledge that for most people, diving is not an objective unto itself, but rather the means to achieve an objective. And, regardless of the specifics of that objective, it always involves some form of interaction with the environment. Unfortunately, due to lack of knowledge, that interaction isn’t always as fulfilling as it could be. Yet, I’m convinced a prime reason why divers often fail to connect more closely with the environment isn’t a lack of desire but a lack of guidance. Quite honestly, most divers simply don’t know that much about the fascinating story passing before their eyes. As a result, a lot of recreational diving comes down to nothing but “bubble blowing” in a world with which the participant is largely clueless. How interesting can that be? So, there’s little wonder why we have long suffered with high drop-out rates and stagnant growth.

The facilitators of the diving experience are (or should be) the professionals who train and guide divers on their journey and, in fairness, some do an admirable job. But not all. The reason for this unfortunate situation should not be laid at the feet of dive professionals. They are only doing what they have been trained—or in this case not trained—to do. What’s more, this knowledge gap seems to be recognized within the diving community as seen from a recent survey conducted by InDepth’s survey partner Darcy Kieran, principal of Business of Diving Institute.

According to The Survey

The 118 survey respondents were split almost equally between scuba divers and dive professionals, with 40 percent of the participants from Europe and 33 percent from the USA. About 10 percent of the respondents had been certified for less than 5 years, 20 percent between 5 and 10 years ago, and 70 percent had been scuba diving for over 10 years. Because the survey participants were not randomly selected, generalizing the results beyond the population of respondents would be speculative. Still, the results are an interesting insight into the minds of those who were interested enough in this issue to respond. Here’s what the survey found.

First, asked how important it was to understand the aquatic environments and the ecology of the locations they dove, 87 percent of dive professionals and 80 percent of scuba divers judged this to be important or very important. This is hardly surprising, but the higher rating from professionals perhaps shows that the issue is more important to them than non-professionals because they perceive their livelihood depends on it. But an unexpected result was that only 60 percent of dive professionals considered the topic to be important to their scuba diving clients. This begs the question, is it possible that dive professionals underestimate their clients’ interest in the environment? If that’s so, then Houston, we have a problem.

Next, the survey asked divers how well they felt their training prepared them for understanding the ecology of the environments in which they were to dive. To that question, just 16 percent of dive professionals self-reported “well” or “very well,” in contrast to 23 percent of the scuba diver population with the same answer. A reasonable conclusion is most scuba divers, both pros and non-pros, believe the environment is a significantly important part of the diving experience, although they feel ill prepared in terms of their knowledge of it.

To me, the most curious result from this portion of the survey was that, while both scuba divers and dive professionals judged quite harshly how their scuba diving courses prepared them to understand the environment, both groups nonetheless appeared to believe their own knowledge was fairly good. Specifically, 78 percent of the dive professionals said their knowledge of the environment was good or better than good, while 70 percent of scuba divers said the same. Having been a diver for more than a half-century and marine scientist for half that, I find this astounding. No doubt some divers are “critter ID” experts; but the reality is that very few divers, and not that many more professionals, have a firm understanding of the functional ecology or relevant conservation issues vital to the habitats in which they dive. I suspect this finding may be an artifact of the self-selected audience who probably does have a higher-than-normal knowledge about environmental issues than the average diver or dive professional.

Following up on their level of knowledge, the survey also explored exactly where dive professionals got their environmental knowledge. Unsurprisingly, 65 percent listed “self-taught” as a major source of knowledge. Other sources reported included: 58 percent from books; 50 percent online content; 45 percent from fellow dive professionals; and 36 percent from the news.

In the realm of training, the survey found that just 16 percent of scuba divers said that their entry-level instructor was interested or very interested in the environment. (If that’s true, ouch!) This is hugely significant because it seems to indicate that while dive professionals believe understanding the environment is extremely important (83 percent), they do not apparently communicate this very well to their students. I believe this is not an indictment of dive professionals but rather the lack of emphasis on environmental education in entry-level diver training and the concomitant low priority it receives in the training of dive professionals.

The question was then asked, where would dive professionals like to get more knowledge of the environment? In reverse order the responses were: 14 percent from DEMA, 28 percent from their instructor trainer or course director, 37 from InDepth magazine/Scubanomics (such a high rating is probably because they were the sponsors of the survey). But overwhelmingly, a whopping 73 percent of professionals felt it was the job of their training agency. Fortunately, some training agencies have begun to up their game in this regard, but to what effect is yet unknown.

Homing in on the preferred method for communicating environmental information, the survey found professionals preferred, in rank order, the following: 82 percent online courses, 82 percent webinars, and 57 percent books. In the digitally-intensive world of today preference for online methods is hardly surprising, but finding that more than half still listed books shows these tried-and-true instruments of knowledge are not yet dead.

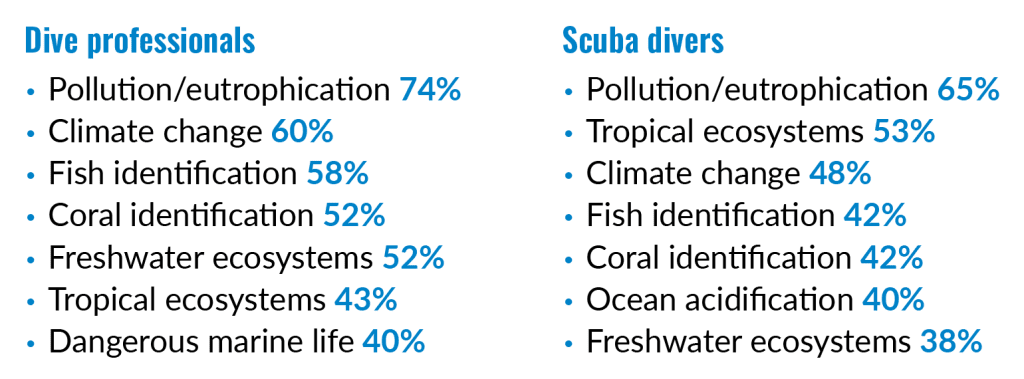

In order to address the apparent desire for more environmental education, the survey asked what topics dive professionals want to know more about and, in rank order, these turned out to be as follows (see below). Similarly, scuba divers ranked their list as well.

Aside from questions about environmental knowledge and whether it’s conveyed effectively, the survey also explored the respondent’s and the dive community’s commitment to environmental sustainability. Here, on a personal level, 82 percent of dive professionals claimed they were committed or very committed to environmental sustainability, with that figure dropping to 67 percent among scuba divers. Again, this higher ranking among dive professionals makes sense, as they likely perceive that what’s at stake for them isn’t just the environment but their livelihoods. But what is most interesting is that dive professionals believe that other sectors of the dive industry are far less committed than themselves.

Just 45 percent of dive professionals rated the dive business for which they work as committed or very committed, while rating their dive training agency as only 39 percent committed or very committed. Sadly, dive professionals had an even lower opinion of the dive industry as a whole, rating it as just 20 percent committed or very committed. It seems all sectors of the dive industry still have much work to do here.

How the Tech Community Can Help

The first step in the scientific method is observation. Clearly, as explorers to places where few others go, technical divers could play a vital role in furthering the knowledge of all aquatic environments simply by systematically documenting their experiences. Fortunately, this task is now being aided through technology by equipment manufacturers such as Paralenz®, making some in situ data collecting a function built into the video recording process. Data collection could be further enhanced by other small and inexpensive recording instruments easily attachable to the tech diver’s kit. Utilizing this passive technology, science could advance years based on the massive amount of data collected.

Still, while collecting data is a vital first step, archiving and disseminating that data is equally important. Here, partnerships such as that between GUE and Project Baseline, which was the organization’s first conservation initiative, serve as an outstanding example of how science and exploration can merge for the betterment of both.

Technical diving has also become a significant part of many scientific diving programs at universities and research centers around the world. Building on this relationship, avenues should be explored in how to translate cutting-edge science to the diving community and the public at large (such as the “twilight zone” research being done at the California Academy of Sciences. Furthermore, by encouraging the scientific diving community to create citizen science programs, data collection could be expanded exponentially, while at the same time increasing the environmental knowledge of divers.

To maximize impact, innovative educational programs could be created by partnering scientific experts with diver training agencies. However, rather than the typical “specialty course” approach, substantive environmental education should be fully integrated into both entry-level diver training curricula and the professional development process to address some of the issues identified in the survey.

Finally, one element which has not really made the transition from tech to rec is the “mission-oriented” nature of technical diving. The idea, as is common in tech diving where more time is spent planning a dive than executing it, is hardly standard practice in the recreational world. In fact, among recreational divers “good dive planning” means, at best, conducting a thorough pre-dive check and hoping that what actually happens under water is what was planned for. But this is understandable because, after all, the goal of recreational diving is to have fun, not accomplish a mission.

However, by developing robust citizen science programs and protocols for data collection, both the safety and quality of experience for recreational divers could be greatly enhanced through shifting the emphasis of a dive from purely leisure to a mission-oriented task. Thus, the invaluable contribution technical diving has made to recreational diving in terms of safety can be emulated once again by improving the knowledge and appreciation of aquatic environments essential to conserving the resources that give meaning to what we do as divers. But, we must act now; time is running out.

Dive Deeper:

Business of Diving Institute: Sustainable Tourism survey

Dr. Alex Brylske is the founder and president of Ocean Education International, LLC, a consulting firm specializing in marine environmental education. He collaborates with companies and NGOs around the world in creating innovative programs dedicated to coral reef conservation, citizen science and sustainable tourism https://www.oceaneducationinternational.com practice. He is a recipient of NOAA’s Walter B. Jones Memorial Excellence Award for Ocean and Coastal Resource Management and was the 2012 DAN/Rolex Diver of the Year. His new book, Beneath the Blue Planet, will be released in the Fall 2022.