Community

The Case for an Independent Investigation & Testing Laboratory

In the light of recent diving accidents, newly retired Scientific Director of the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) Dr. John Clarke, makes the case for an independent community-based accident investigation and equipment testing lab, similar to the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), to provide vital information back to the diving community can improve diving safety. As Clarke points out, “A diver’s death should mean something besides a medical examiner’s verdict of Cause of Death: drowning.” He is hoping to start a discussion. Please chime in!

by John R. Clarke Ph.D.

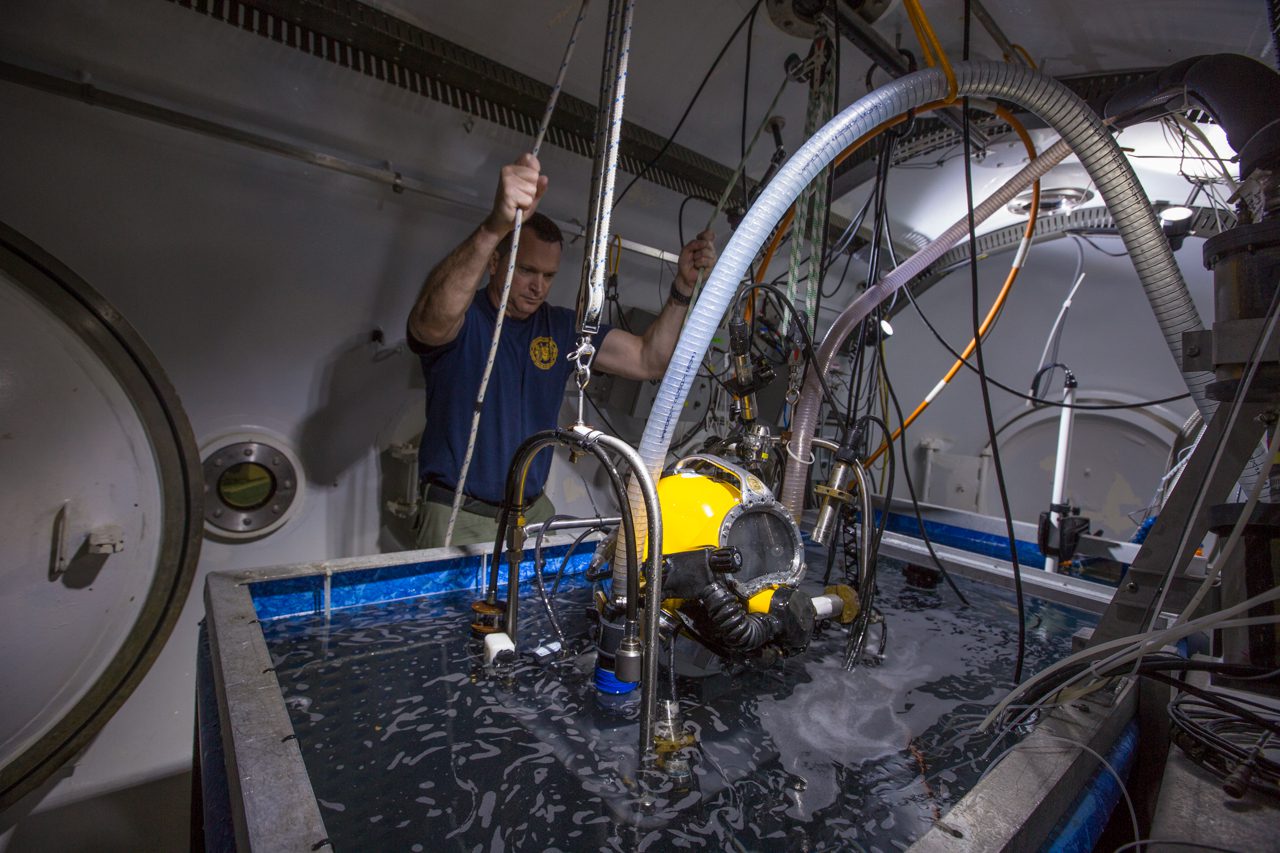

Header photo by Stephen Frink. Navy Experimental Dive Unit, Panama City, Florida.

With the recent loss of yet another loved, experienced, and competent rebreather diver, Fiona Sharp, MD, I would like to offer an idea whose time has perhaps come.

Until approximately ten years ago, the US Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) tested new underwater breathing apparatus (UBA) and investigated UBA-related diving accident cases. Those cases were either military, or forwarded by the U.S. Coast Guard and, sometimes, by Medical Examiners. As the number of civilian cases increased, the time burden on NEDU’s Test and Evaluation laboratory became so all-consuming, that NEDU restricted outside accident cases to those UBA of military interest. They also started charging the fair cost for outside examinations. Not surprisingly, accident cases reviewed by the Navy have since plummeted.

Rebreather diving is very much like flying a small airplane. It’s highly enjoyable, highly technical, and quite useful; but also expensive, and in certain circumstances, lethal.

An aviation accident is accompanied by a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation, which uses a recognized methodology that covers technical, human factors, environmental, social, and organizational factors. However, there is nothing similar for Scuba and rebreather diving accidents.

Most aviation accidents are pilot-induced, but not all. If there is an equipment or a procedural problem, the entire aviation community is alerted. Recently, after a wing fell off a Piper Arrow—in-flight!—just such an alarm went out.

Before I retired from NEDU, a couple of civilian accident cases came to me, which I forwarded to Gregg Stanton and Wakulla Diving, since government labs cannot compete with private industry. Gregg was doing some investigations but lacked an adequately-sized pressure chamber. Moreover, the business case for private accident testing laboratories is non-existent, and I don’t think existing civilian facilities can do what is needed in the long term.

A couple of months ago, I was contacted by a rebreather manufacturer to see if I could arrange Navy-approved laboratory testing of their new rebreather design. I put him in touch with Kirby Morgan Diving Systems’ Dive Labs, but the Dive Lab schedule is taken up with not only their own needs but also an overflow of military testing. Even NEDU can’t keep up with the military’s testing demand.

As a result, some manufacturers might not be able to properly test their rebreathers before going to market, or after making design changes. Arguably, that’s not a good thing. Also, if there is an accident that needs investigating, like Fiona Sharp’s, where would we find a neutral third party to look at the ‘system’ as well as technical equipment issues?

I think we can all agree that the case of underwater filmmaker and photographer, Wes Skiles, was tragic. Ultimately the jury decided that neither the equipment nor the manufacturer was at fault, but that sending the accident rig to Dive Rite for an initial evaluation was conflict of interest. That does not mean that things were done wrong. However, it does mean that extra care is required to ensure that things are not done wrong. In my opinion, it would have been far better to seal the UBA for immediate transport to a neutral investigation team.

Funding Options

An independent testing laboratory might initially be funded by manufacturers who want their equipment tested to Navy or CE standards. With proper protections in place, that laboratory could also conduct accident investigations. Rationally, it should use a recognized and standard methodology like the Human Factors Analysis Classification System (HFACS).

People buy time-shares in private jets to make them available when needed; a similar structure could be used to make testing equipment available on a “as-needed” basis. That way, when an accident case comes in, the laboratory would have the equipment and knowledge to conduct accident investigations pro-bono. Alternatively, taxes from scuba and rebreather sales, dive education, or dive resort diving fees, could perhaps sustain the facility. Of course, time and expertise could be purchased on a one-off, case-by-case basis.

I am firmly against having the parties in litigation pay a testing laboratory. Consider the history of tobacco companies paying scientists and their laboratories to test the safety of tobacco products. It’s a sad fact, but money talks, even to scientists.

Admittedly, I’m a scientist, not a businessman, but the more I watch beautiful people dying in the water, and after observing the sometimes shoddy investigations that follow, I recognize that, well, it just isn’t right. A diver’s death should mean something besides a medical examiner’s verdict of “Cause of death: drowning.”

Just imagine if the NTSB cited the cause of death for pilots and passengers as “Crashing.” There would be public outrage, and neither pilots nor aircraft manufacturers would learn anything from it. In fact, the NTSB used to do just that, and called it ‘pilot error.’ And then, they realized that by analyzing cockpit voice recorder data and flight data recorders, the ‘pilot error’ was, in fact, a convergence of multiple systems and human factors.

The Navy considers both aviation and military diving to be a high-risk activity, and it goes to great lengths to manage those risks, usually with great success. Rebreather divers and training organizations also go to great lengths to manage risks. However, what seems to be lacking from some water fatality investigations, are the “lessons learned.”

Dissemination

What good is knowledge gained from an accident investigation if it isn’t disseminated to the diving community at large?

NEDU diving accident investigation reports are rarely released to the public. One exception is the report on the death of cave diver Richard Mork in September 2008. It was released to the world by Mork’s widow.

NEDU’s video deposition during the Wes Skiles fatality trial was also released through Courtroom View Network. Unfortunately, the testimony was not particularly revealing since the UBA components evaluated by NEDU were so fragmentary.

To help prevent future diver fatalities, the publication of investigation results is essential. Arguably, that would be a more difficult task for an investigating agency that receives its funding from equipment manufacturers. Impunity from adverse action for their reports is precisely why the NTSB is so effective in improving aviation safety; they are not beholden to aircraft manufacturers or pilot unions.

Since the threat of litigation has a stifling effect on dive accident reporting, will legislation protecting an independent investigation be required? That is something to consider. Hopefully, Giugi Carminati and David Concannon, or other attorneys, could contribute to this discussion.

The Complete Package

The UK’s Gareth Lock, founder of the The Human Diver, does a superb job of explaining the human factors side of risk management, but who does the equipment investigations, and how do they join up? In my opinion, we’re missing a critical factor in the risk avoidance equation.

I do not consider the court of public opinion via Facebook and rebreather forums to be the best we can do in terms of preventing future accidents. What do we divers learn from the deaths of Wes Skiles and Fiona Sharp? Until we recognize that we are all fallible and that those same issues can apply to us all, irrespective of experience and position, then diving safety is not likely to be improved.

Perhaps it’s time to restart this conversation.

Editor’s Note:

Beginning in June 1993 with aquaCORPS #6 Computing (my old magazine from the 1990s), we added a new section called “Incident Reports,” in response to the spate of tech diving deaths in the summer and Fall of 1992. It soon became the best read section of the magazine. In it, we reported on fatalities and serious injuries that occurred in between publishing issues. I personally did much of the reporting. I would call the people involved after the news of an incident surfaced and write a non-judgemental report sans names stating what was believed to have happened, so that we could all learn from incident and hopefully improve diving safety. In total we reported 45 incidents between late 1992 to 1Q 1996, when aquaCORPS closed its doors.

Sadly, today, of course, this kind of reporting is almost impossible in most cases for fear of legal action—almost no one is willing to talk. However, even after legal cases are settled or dismissed, seldom is the relevant information forthcoming, i.e. what happened. As John points out in his post, we the diving community are the losers. However, I also recognize, that sometimes, the families don’t want information released. I respect that. I hope that you will share your thoughts regarding John’s ideas. Thank you.

DIVE DEEPER

Alert Diver: A Profile of NEDU: Deep In The Science of Diving, Alert Diver Q3 Summer 2016

Divers Alert Network: Rebreather Forum 3 Proceedings

-“Rebreather Accident Investigation,” by David G. Concannon, pg 128

-“Post-Incident Investigations Of Rebreathers For Underwater Diving,” by Oskar Frånberg, Mårten Silvanius, pg.230

John Clarke, also known as John R. Clarke, Ph.D., is a Navy diving researcher in physiology and physical science. Clarke was an early graduate of the Navy’s Scientist in the Sea Program. During his forty-year Navy career, he conducted physiological research on numerous experimental saturation dives. Two dives were to a pressure equivalent to 1500 fsw. For twenty-eight years he was the Scientific Director of the Navy Experimental Diving Unit in Panama City, FL. Although recently retired, Clarke still works for NEDU as a Scientist Emeritus and contractor, when he isn’t writing about diving, aviation, and space. He has authored a technothriller-science fiction series called the Jason Parker Trilogy available at Amazon and Barnes & Noble. His websites are www.johnclarkeonline.com and www.jasonparkertrilogy.com.