Cave

The Apprenticeship: Cave Diving with Sheck Exley

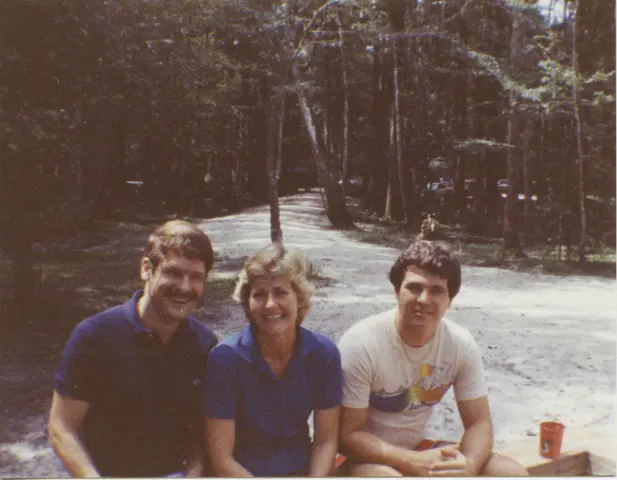

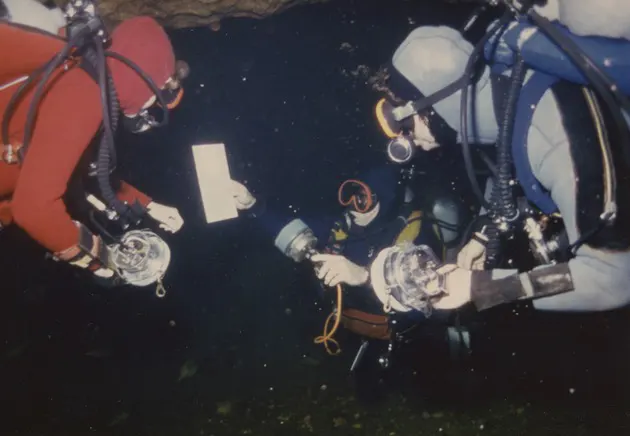

by Bill Stone. The story was first published in International Caver magazine in 1981. Images courtesy of Brian Udoff and Mary Ellen Eckhoff.

I lay back in my seat and relaxed as the 727 lifted out of Washington International. This trip had been three months in the making, and I relished the prospect of three days of training in a most arcane discipline. The subject was deep cave diving, and my instructor was widely regarded as one of the nation’s most experienced cave divers. I had read his publications and heard a grapevine tale or two around a campfire, but a personal acquaintance with one Sheck Exley Jr. was a yet-to-be realized experience. The trip had come about through a most unusual set of circumstances.

Bottoming Out Huautla

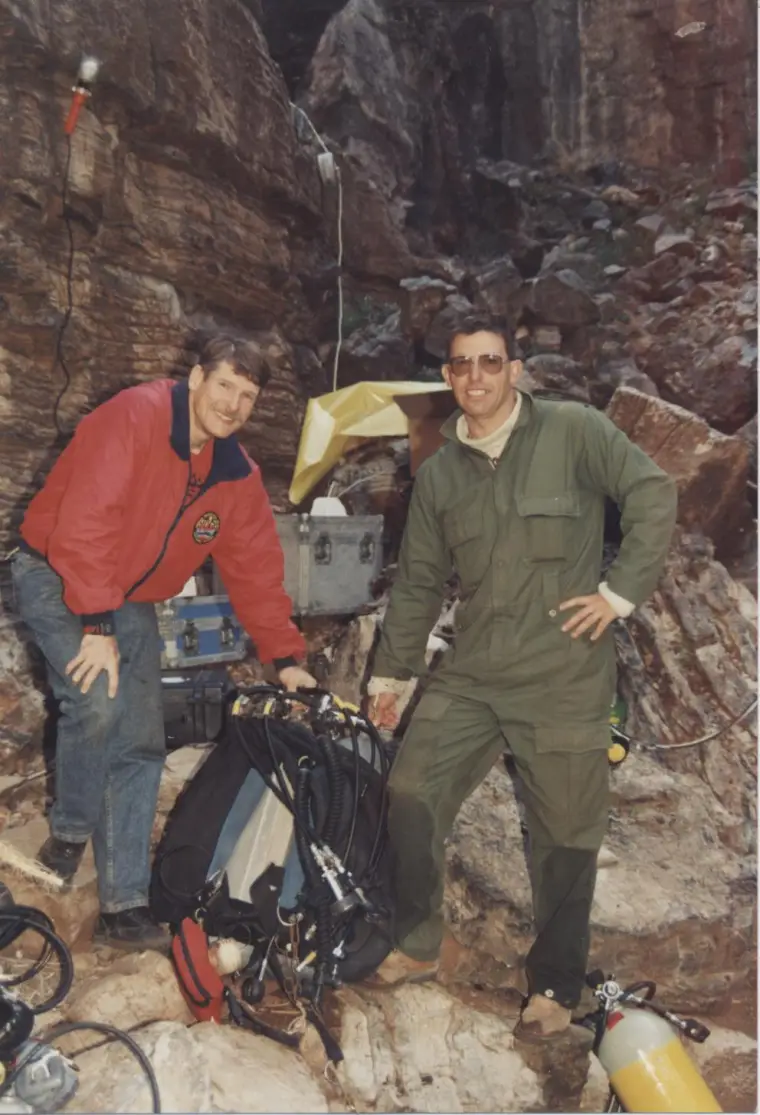

For some five years, the US Deep Caving Team—of which I was a member—had been working its way ever deeper into the Huautla Plateau in southern Mexico in an effort to “climb Everest in the other direction.” In other words, to ferret out a route to the bottom of what may be the world’s deepest natural abyss.

During a three-month expedition in the spring of 1980, we had the good fortune to link two components of that extensive subterranean network to form a system with 1,220 m/4,004 ft of vertical differential, establishing it as the world’s third-deepest hole. Upon returning to the States, a careful scrutiny of the computer-processed line map revealed that we could achieve a depth of 1,356 m/4,450 ft by connecting in another known, higher entrance which had already been explored to -30 m/-100 ft and was continuing down a geological lineament toward the lower caves. This connection, if achieved, would advance the complex into second place and leave a scant 52 m/170 ft separating it from the world’s deepest cave: the Reseau Jean Bernard in France, currently 1,410 m/4,625 ft deep.

The dilemma of attaining those extra 52m/170 ft diverted our attention to the idea of extending the bottom of the Huautla system. There we had encountered a massive clearwater “sump” where the subterranean canyon had completely filled with water due to a local geologic perch-ment, not unlike a sink drain trap. The logical next step was an attempt to traverse the flooded stretch to airspace beyond using scuba gear. Should such a gamble succeed—and there was no assurance that the “drain trap ” might not just be 122 m/400 ft deep and impassable—it would be possible to ditch tanks on the far side and carry on with the exploration to the resurgence: the site where the confluence of the stygian flow exits the base of the plateau, 427 m/1,400 ft lower. In fact, we had already launched one such attempt during the spring of 1979 using miniaturized lightweight equipment. That dive, although brief—a penetration of 40 m/130 ft to a depth of 8 m/25 ft—had earned us a strategic view of the watery chasm that stood beckoning before us… unexplored … and deep.

Cave diving, in itself, is a sport requiring much gadgetry, skill, and consummate level-headedness. When all the rules are observed, it constitutes a safe and thrilling tool for pushing back one of the most challenging frontiers of cave exploration.

Unfortunately, one of those rules calls for “avoiding deep diving in caves”—the very instrument by which one might pop through that mighty drain trap at -4,000 feet and into the galleries beyond. Deep diving’s coterie of evils ran the gamut from “the bends,” inert gas narcosis, and oxygen poisoning, to the most insidious and the subtle “deep water or depth blackout”—all of which, in some form or another, had contributed to the few fatalities among the experienced cave diving community.

Nonetheless, many extremely experienced divers were routinely making forays to depths in excess of 100 m/328 ft in totally submerged caves. They had developed special techniques to muster physiological and psychological tolerance to diving at depth on compressed air. It was this knowledge I had come to seek out.

Meeting a Master

The intercom sounded off abruptly: “We will be landing shortly in Jacksonville, Florida. Please fasten seatbelts.”

I staggered off from the baggage claim loaded down with four duffel bags of diving gear and stared impatiently into the crowd of suit-and-tie businessmen. One of them pensively observed my predicament for a moment then, with a smile, stepped forward and said, “Hello Bill. Need some help?”

I lifted my head incredulously—at first not penetrating the sartorial guise —and prepared to say, “No thanks, I’m waiting for Sheck Exley in some Army dungarees to take me into the swamp to dive flooded caves” But my oversight was quickly corrected, and the two of us made our way out into the front parking lot where Sheck’s VW van was baking in the hot Jax sun.

“We may have to move a few things here,” he said offhandedly, opening the side door.

Suddenly a regulator tumbled to the floor and a set of twin 104s shifted with a resonating clang. I glanced over his shoulder and suppressed my laughter. The inside looked just like the back of any pickup truck I had seen heading off for an extended caving expedition in southern Mexico—which is to say, crammed with a literal arsenal of technical equipment waiting to fall out the moment the door was opened. The striking difference in this particular case was that all of it—nearly every cubic foot, save enough to cram in a driver and passenger—was packed with apparatus indigenous to diving, and then some.

This is going to be a treat, I thought to myself as we sped down the interstate trading the latest exploration stories.

Sheck, being a prudent businessman, spends most of his time—when not cave diving, that is—as general manager of the family-owned Volkswagen dealership at the west end of town. It was from here that he had come to pick me up at the airport. Still having a few matters to attend to before careening off into the swamps for the holidays, he dropped me off at his house and bid me to make myself at home for a few hours.

There was nothing unusual about the place: the typical single story Jax ranch house nested in a sparse pine forest with soil so sandy the grass barely took hold. What did catch my attention was the two car garage.

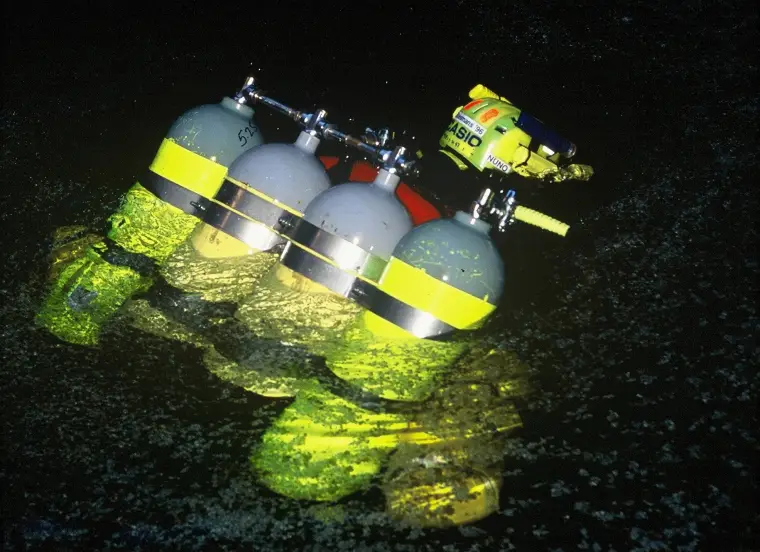

From the first glance it was obvious that it had not been employed for its intended use for quite some time. That was because it too was full of diving gear! Apparently an overspill from the van when the door was left open too long, I reckoned. In one corner, a bright orange torpedo projected from the pile. More specifically, it was a Farallon DPV-5: a high-powered, self-propelled, underwater scooter the likes of which Exley and his cronies —not all of whom were “Aw shucks, it weren’t nothin’” Southerners—used.

In truth, some of his buddies were expatriate yankees who had actually moved to the northern Florida swamp land to get in on the hot diving that was going on and had been using it to knock back the unknown frontier in Falmouth Springs to nearly a mile beyond the nearest airspace.

When you saw one of these ungainly contraptions in use, the first thing that came to mind was, “But that’s not the way they did it in Sea Hunt?” You actually straddled the bugger, hunkered down, and held on for dear life like you were riding a high performance motorcycle for the first time. Add to that all of the usual four sources of light, dual valve manifold double tanks—huge tanks filled beyond the manufacturer’s recommended service pressure so you could get a few thousand feet further without carrying extra cylinders—buoyancy compensators, line reels, and a Medusan array of hoses, pressure gages, and regulators…and you had a veritable apparition out of a James Bond movie…or the typical front-line Florida cave diver off on a serious “penetration dive.”

I was engrossed in studying this device when another VW van pulled into the driveway, and Sheck’s wife Karen—an attractive five-foot-seven brunette—stepped out and introduced herself. Following a few short formal exchanges, we got onto the inevitable subject of cave diving.

“Are you, ah … into this too?” I served the quintessential question.

“Well, used to be,” she explained. “I was into it quite a bit, really. Made it to 260 ft over in Numero Uno sink once, and helped on a number of surveying projects.”

She was candid with me about how, for her, things started stacking up. For example, with all the stage diving and longer and ever deeper dives, the chances for “buying it” due to some minor oversight or a strange variety of depth blackout—the likes of which did Bud Jenkins in at 79 m/260 ft in Numero Uno in 1974—made up her mind to take up something less stressful (like going to pet shows, as it turned out) and let Sheck pursue his obsession unhindered.

Preparing to Make the Jump

Four hours later, Sheck and I pulled into the head of Orange Grove sink—way out in the Peacock Slough swamp district of Suwannee County—and stepped out among the cypress trees, Spanish moss, and no see ‘ums in the failing light of dusk. Shortly, a battered white Dodge van rolled in behind us, trailing a swirling cloud of dust. Three college-age, lean, but sturdy men clad in shorts and tennis shoes climbed out and walked toward us.

“Well, how’s the fair-haired boy from Valdosta doing?” Sheck hailed.

“Been overworking Madison Blue,” the leader replied. “You finished that map yet?”

“Yeah, but you can’t see it,” Sheck fired back, and then burst into a hoarse laugh that came from down deep—the kind you can do only by inhaling.

That was one of Exley’s trademarks. And that was the way these two would normally greet each other: parlaying back and forth to see who pushed back the limits of what hole and subtly trying to pry loose that one morsel of information that would allow them to go back there and one-up the other.

The fair-haired boy from Georgia was Court Smith, a cave diver of some reputation in these parts. Court was also a man Exley had much respect for—and, in fact, dove with quite often when things required teaming up for a heavy duty push (like Madison Blue Springs).

Sheck drew a tube from the back of the van and rolled out its contents on the ground: the latest map of “Blue Springs, Madison,” as the label read. They always put the geographic connotation at the end, for it turned out that there were around twenty-odd “Blue Springs” in this neck of the north Florida bog and one had to keep track of them somehow.

Sheck slowly drew his index finger along one set of parallel lines and tapped the spot where the solid lines changed to dashes and abruptly stopped.

“We ran into a fairly nasty breakdown here on the last trip, but the flow is still good,” he said.

“How many stages?” Court queried.

“Four…and we finned it too!” Exley chuckled.

In the parlance of Florida cave divers, a “four stage” dive meant that to reach the penetration limit—1,463 m/4,800 ft from the nearest airspace in this case(!)—four sets of tanks had to be strategically pre-set far within the cave during several “pre-push” dives. Often, they used those bright orange torpedoes to assist in staging tanks. But, in this case, 300 m/1,000 ft back in Blue Springs, Madison, there happened to be a constriction called ” Rocky Horror” where you had to turn sideways and squeak through a passage so tight that grooves had been worn into the wall marking the passage of the few divers that had been beyond it. As it turned out, it had a bend in it which made it impossible to push their scooters through, so they had “finned it” from there to 4,800 ft in, and then back out, all the while picking up and ditching stage bottles.

Only one third of the air in each stage tank was used on the way in before it was exchanged for the next one. The “1/3 Rule,” as every cave diver that survived their first fifty dives has emblazoned on their heart in letters of gold, is the primary rule for air consumption planning on a cave dive. Only one third of the starting tank pressure is used for the push. The remaining 2/3 is to come out on, theoretically leaving a sufficient safety margin to get you out should trouble arise.

And trouble could come at any moment in a plethora of forms: A zero-visibility silt-out could occur by simply passing too close to a fine mud floor with your flapping fins, and you would have to grope your way out along the guideline blind. Then there was always the rare possibility that both of your buddy’s dual independent regulators would fizzle, and you would have to buddy-breathe out on your 2/3 tank of air—always a stressful procedure with the clock ticking down the seconds at every breath. It was based on the latter consideration that Exley devised the thirds rule back in 1968.

By the year 1980, that rule was well established as one of the basic tenets of safe cave diving. Every push diver from Valdosta to Jacksonville out there on Friday night hunkered down on his screaming orange torpedo was casually and methodically monitoring that Medusan array of hoses and gauges that would safely get him to his fourth stage bottle and on to the limit of exploration, all so he could sublimely one-up Exley, or Smith, or Dr. John Zumrick, or any of those hot divers in that small fraternity at the top.

Secretly, however, what every one of them was praying for was what the Australian cave divers had found out in a vast salt scrub wasteland in central Australia known as the Nullarbor Plain. Out in that treeless, sun-parched skillet—accessible only by a 12-hour stint of four-wheel driving—the Aussies had “scooped” the world’s longest underwater penetration in Cocklebiddy Cave: more than 2 km/6,651 ft from the nearest airspace, and still going when they were forced to turn around. What Cocklebiddy had going for it was depth—specifically, the lack of it. Most of the dive profile was spent in water only 5 m/15 ft deep. At that depth, your air lasts practically forever, and no decompression whatsoever is required.

Not so in Florida. The biggest, the clearest, and most challenging springs in Florida all went deep, some of them pushing towards -110 m/-360 ft… and still going down! Operating at those depths, there was no way you could even hope to challenge the Cocklebiddy length record.

So why dive deep?

Any caver that has stuck with his sport through thick and thin ultimately comes to realize that the all-encompassing lure of cave exploration (the “primal drive,” as it were) was not about one-upping your friends, or wowing other cavers around the world with your exploits of the longest, the deepest, or whatever—although those can certainly be fun at times, too!

The real lure was that indescribable bliss of being where no one had ever been before—indeed, where no one might ever go again—that brought it all together year after year. Cavers, in their somewhat eccentric elocution, had even synthesized a name for the distilled essence of that virgin exploration experience: “The Booty.” And cave divers, just like their landlocked comrades, “Went for the booty,” indeed, with a passion bordering on obsession. This was basically how deep diving became not just a useful skill to the hottest Florida divers, but an absolutely essential tool to reach the best booty!

The First Dive

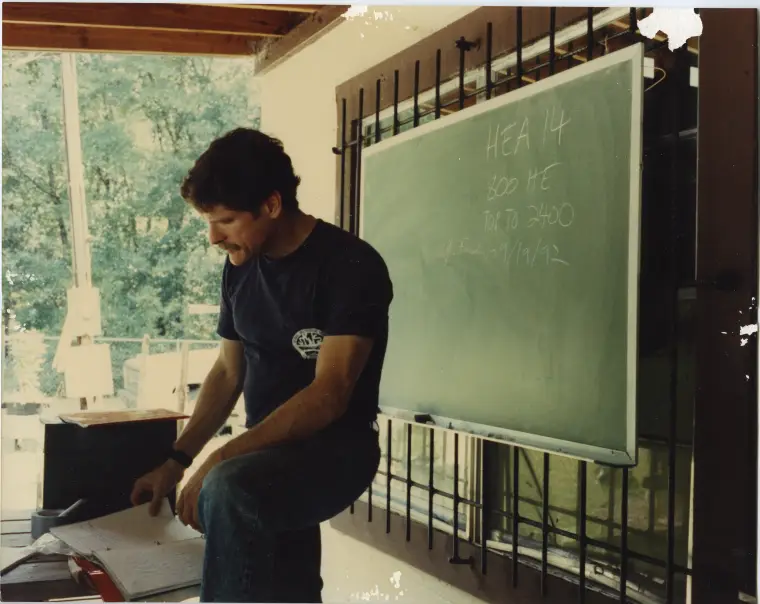

I staggered from the van with 64 kg/140 pounds of steel, hoses, gadgets, and gauges and made my way down the path to where Sheck and Lamar English were floating in the limpid waters of Orange Grove Sink. Sheck briefed us on the dive profile: basically a “bounce” dive to 40 m/130 ft to get used to those huge overblown 104s. Floating there in a triad in the crisp moonlit night, we commenced the usual pre-dive checkdown of equipment. Exley would start off:

“Three sources of light?” Each of us would flash our waterproof dive lights to assure they were functioning.

“Check.”

“Starting pressure? ”

“3600,” “2500,”, Lamar and I each called out in succession.

“Turn around?”

“2400.” “1800.”

“Correct,” came the reply. “Spare regulator functioning?”

We each presented our second independent regulator and depressed the purge button, whereupon a gust of high pressure spray issued forth as the water was blown from the mouthpiece. “Check.” And so it went.

With the guideline tied off, we punched the deflate button on the buoyancy control packs and slowly sank below that mirrored interface separating here from there. The sensate dichotomy was stunning. One moment you were floating in a great fermenting circular sump out in that god-forsaken north Florida swamp, with dodder vines and Spanish moss hanging pendulously overhead, and the next you were free falling—arms and legs stretched out in a tracking position like three slow-motion skydivers—into that great black gulf below.

About that time, Exley reached down to a long plastic cylinder riding at waist level and twisted a rotating switch. Instantly, the place lit up like Three Rivers Stadium for a Steelers night game. High-powered primary lights—using either sealed beam aircraft landing lights or movie projector bulbs—were another of those useful and innovative items that had been incorporated into the Florida cave diver’s endless cachet of gadgets. In the big deep springs with clear water, you could beam 300 ft down those yawning corridors with one of those lights.

There, in the less grandiose entrance chamber of Orange Grove Sink, it brilliantly illuminated every seam, crack, hole, and eroded block of white limestone with crystalline clarity. At 24 m/80 ft, we were still free falling 30 inches from the nearest wall, floor, or ceiling and headed for an oblique hole in the jumbled breakdown floor. Single file, Lamar in the lead with the spool, we wormed through the stacked slabs and emerged into a steeply sloping fissure.

At 40m/130 ft, Exley pointed the way and drew his hands together indicating things got tight beyond there. He then flashed the thumb signal for heading up. Following a brief diversion in a side passage, Lamar reached the one-third limit on air and called the dive. A well-equipped diver with large enough tanks could follow that particular gallery some 1,981 m/6,500 ft to emerge in a remote sinkhole entrance of the extensive Peacock Springs cave system. Exley, Court Smith, and four others had spent some five years mapping the complex’s 6.7 km/22,000 ft of passage: the world’s longest known underwater cave.

At 9 m/30 ft, we calculated our required decompression schedule and began that uniquely boring experience whereby you try to hold your elevation precisely at the prescribed coordinates for the compulsory period while attempting to amuse yourself with whatever happens to be close at hand: small fish that swim up to your mask, knowing full well you aren’t about to leave your grim post to chase them; or, more likely, the sight of Exley, hands clasped like some pious saint in silent prayer, floating there—right on the money—and not touching a damned thing! All the while, he is sympathetically watching as I cling to the wall for dear life at 3m/10 ft so that I don’t bob to the surface or sink back into the depths and violate those sacred decompression schedules. The Navy says you have to be right on the money.

More than that, though, it is that face behind the mask that rivets my attention. It is not the visage of the “aw shucks, ain’t nothin’ serious, hoarse, inhale-laughing pre-dive Exley…but more the incarnation of the solemn grand master, carefully scrutinizing the progress of a promising, but floundering, pupil. Precision buoyancy control, as was being demonstrated before me, was the first plateau in my tutelage. I had much to learn.

Narked at Mount Sink

Just twelve hours later, we were back in freefall—this time in Mount Sink, some thirty miles up the road—with six of us making that “power dive” into the depths. Mount Sink, unlike Orange Grove, had an air of evil permeating its tannic-stained bowels. From where the guideline was tied off at 3m/10 ft, the floor simply dropped out into this massive canyon and was never seen again until the needle on my depth gauge crept past 46 m/150 ft. To add to its malevolent ambience, the visibility was reduced to a scant 5m/15 ft by a heavy concentration of tannic acid and particulate matter which had drained in from the surrounding bog.

It was there, at 49 m/160 ft, that I first met that fuzzy threshold—that edge of the envelope—where things started slowing down around you and the exhaust bubbles from your regulator crash off in undying echoes through your numbed synapses.

And that little voice in the back of my head was saying, What… is … going … on …. here?

Then suddenly, no worse than if Lucifer himself had appeared before me, a cold bolt of blue lightning ran down my spine and that little voice exploded:

I am 160 ft down in this freaking black sump and NARKED!

Then another voice cut in and said, “Keep cool. You are in control. Keep cool!” Meanwhile, that FACE (and those clasped hands in solemn prayer) floated in front of me, not touching a wall, a guideline, or anything, but nonetheless right there on the money: watching, making mental observations of my pathetic condition.

And then those hands rose towards me, pointed the way in, and gestured, “A little further, come.” I checked my pressure gauge—still plenty of air left—and followed cautiously along, my right hand forming an OK signal with the guideline—the only safe route out of this place—firmly entrapped between my thumb and forefinger.

We went only 3m/10 ft deeper, although 61m/200 ft further in, before bottoming out. Following decompression, we lumbered up the path— good 91m/300 yards through the forest this time—with gear clanging and feet dragging.

It was while driving to the next “lesson” that Exley—now known as Smilin’ Sheck—imparted some wisdom on deep diving. Being “narked“ was diver jargon for that impairing (and sometimes terrifying) intoxication that comes about from breathing compressed air at extreme depth. More specifically, it was from breathing the inert portion of the gas—nitrogen— which led to the syndrome of nitrogen narcosis, more popularly known as “rapture of the deep!”

As it turns out, rapture of the deep is more than just a simple physiological reaction to breathing nitrogen at depth. It is a complex function of depth and bio-feedback that can either be fueled or dampened depending on the mental state of the individual. “Physiologically,” Sheck said, “narcosis is not time-dependent. The minute you reach 200 ft, you are as narked as you are going to get at 200 ft.”

But several factors can influence how narked you feel. The dive environment—be it warm and alluring, like a sunny day in the Bahamas, or dark and threatening, like the tannic-stained depths of Mount Sink—is one important factor. “For some unexplained reason,” Sheck went on, “we have found that a diver at 300 ft in a cave will suffer more from narcosis than a diver at around 400 ft doing wall dives in the Bahamas.”

Perhaps that was due to the psychological pressure on the cave diver. Wherever they were, they knew they couldn’t “punch out”—hit the buoyancy control button that would send them rocketing to the surface if something went wrong. No, the only exit for the cave diver was out: back along that thin guideline stretching off into the murk.

The real danger of narcosis, in either environment, was that it brought your consciousness ever closer to the edge of that invisible failure envelope known as panic.

Once you reach that threshold, the heart begins to pound as the adrenaline roars through your system—just when you don’t need it!

Respiration picks up dramatically.

Vision narrows.

In a state of panic, novice cave divers have been known to drown only 15m/50 ft from a sunlit entrance, paralyzed with fear from a zero-visibility silt-out. They just sat there until they ran out of air.

You could do that at 61m/200 ft, too; but, at that depth, an insidious secondary factor creeps in. As you near the panic threshold, the respiration rate increases and breaths become short, allowing carbon dioxide levels in the lungs to reach dangerous proportions. At some ill-defined concentration, the mind just goes blank, and (worst case scenario) you would float there, staring at the wall, until your tank ran out of air.

This “depth blackout,” as the divers referred to it, was the ultimate fate awaiting the individual who let themself become entrapped in that spiralling cascade of stress at depth. The truly bad thing about depth blackout, however, was that it could sneak up on even the best diver—one not likely to panic from narcosis—if he happened to be swimming too hard for some reason (working against a strong current, for instance) and worked up a heavy respiration.

“Psychologically, you build a tolerance to narcosis by becoming intimately familiar with your equipment and surroundings—essentially adapting out of the possibility of panic—and by working up to depth in a series of graded increments,” Sheck relayed.”Physiologically, you can surmount depth blackout by avoiding excessive exertion at depth and by taking long, complete breaths to reduce carbon dioxide retention.” The rules of the game were, by then, becoming clear to me.

A Car? What the…

I took long, complete breaths. I had started that breathing drill even before we had finished finning across the verdant duckweed slick capping Dumaflage Sink—one of Florida’s deepest open water sinkholes. [Ed. note: The sink was purchased by Hal Watts and renamed “Forty Fathom Grotto.”] Had it been dry, and in Mexico, the locals would have referred to it as a “Sotano,” a great, truncated, conical shaft belling out into the stygian miasma.

Once we crossed that dividing boundary between air and water and began descending the fixed line, we might as well have been in outer space. Even with 24m/80 ft visibility, there are no walls: only a bluish mist which swallows even those potent aircraft landing light beams.

It’s like flying in formation in a blue fog. And, all the while, that needle on my wrist keeps spiralling clockwise… 120..140..160..180!

That crashing echo of bubbles escaping from the regulator is back in my ears. My mind is buzzing like the tail end of one of those rowdy weekend beer calls back in college. At that point, a car suddenly appears a few feet below me, rising up fast.

A car! What the .. ?

Hit the buoyancy control, says the little voice.

Hit the …

Crash. I land on it with a dull thud.

“Whuh?”

“Ah… Make a little note here, will you?” the voice says.

“‘Reaction time slowed at depth.’”

We continue on, leaving the rusting spectre on the floor. At 206 ft, Sheck motions to me to head up. We have met the prescribed graded increment in depth. I depress the inflator button—negating the descent momentum—and we slowly fin back to the shotline.

“Smoothly—no heavy exertion,” says the voice. All the while, I am consciously following that breathing drill.

At 40 ft, things are back to normal: as clear as if we had never made that intoxicating plunge. We decompress while swimming around the sinkhole at the prescribed depth coordinates.

What? You don’t have to cling to the wall for dear life?

That was news to me. It proved considerably easier to maintain a specific depth in motion than while floating free. “Turns out it’s better to keep things moving,” Sheck said when we surfaced. Although he didn’t say it at the time, that was the latest recommendation from the horse’s mouth himself: Dr. John Zumrick, a Commander atf the Navy’s Experimental Diving Unit, with whom Sheck dived often.

And the cars? Well, the sinkhole happened to be fairly close to a back country dirt road, and the locals made a habit of pushing their junkers into the hole.

“How did you feel?” Sheck queried.

“Pretty good, all things considered,” I responded.

“Good, we’ll do Eagles Nest tomorrow then,” he said, nodding to himself.

For some reason, I had received the impression that we wouldn’t be diving all that deep in Eagles Nest Sink—just another proficiency run.

The Edge of the Black Hole

The following afternoon we made our way out into the savanna grass and stunted cypress swamp north of Cedar Key. We stopped near a large circular pool all but hidden in the grass.

“This looks like gator country!” I exclaimed.

“It is.” Sheck replied. “We came out of here after decompression one night and ran into a four-footer. But don’t you worry none.”

“How’s that?”

“They take one look at you in that rig and they’ll run for dear life! Ha…Ha,” he chuckled.

All the while this had been going on, he was filling a net bag with paperback books and tubes of squeeze-type food. Next to this, he placed a green cylinder marked “Oxygen.” About this time, it dawned on me that this was not going to be an ordinary dive.

“Oxygen for decompression?” Bill Oigarden, one of the others in our party, queried.

“Ah, yep,” said Smilin’ Sheck, whereupon he outlined the planned dive profile. “Well, we’re only going to 100 ft.

Oigarden ended with, “Y’all have fun !”

Lost Sink, as the place is sometimes (and more accurately) referred to, was the drain plug for a large section of the Cedar Key swamp. In times of bad weather, the rain would leach out all sorts of evil things from the bog and carry them down to this pool where they would descend to some unspecified level before coming into equilibrium with the back pressure from the clear spring water. On this particular day, the place was in grand form with that amber-colored tannic rot reducing visibility to less than five feet.

Ben Johnson, Sheck, and I paddled out through the soup to where a dead cypress tree lay angling down into the murk. After stowing the oxygen tank at 6m/20 ft, we clicked on the dive lights and made our way down the fixed guideline. Within a few feet, it was totally black; the brilliant afternoon sunlight had been blotted out in the ochre broth.

At 50 ft, the basin funnels into a small vertical tube, much like an hourglass. In succession, we pull into a straight-up position, dump the air in our buoyancy packs, and drop like firemen to a boulder pile 50 ft below. At 130 ft, we break through the tannic cloud and into a vast chamber. The beams on those big lights now come into full play, searing across the aqueous void. We have 200 ft vis!

I can barely break my attention from the view. It is riveting, like something out of a caver’s wildest dream: Huge, booming borehole—a tremendous gallery—arching down, down, down. And right in the middle of this surreal picture, as if suspended in midair by invisible threads, two tiny figures are playing laser-white beams back and forth across the gulf. I punch the buoyancy pack control and lift off into the void, following along at roof level.

Slowly, the steep boulder pile begins to level out. The floor is now carpeted with a velvet layer of silt and some occasional fallen blocks. I glance at my depth gauge and find the needle creeping past 220 ft. The air pressure gauge reads less than one sixth down. All systems go.

I catch up with the others at 232 ft. Sheck flashes the thumbs up signal: dive called. He had started off with a lower tank pressure and was now at his cutout point. We have also reached the desired depth.

As I turn around, there is a strange, disorienting feeling.

Something is gravely wrong.

Only now do I become aware that I failed to hit the inflator on the buoyancy pack after meeting up with the others.

“Reaction time slowed at depth.”

Since they were at a lower level, I had been in a slow descent pattern. That momentum unchecked, I had spiralled down towards the floor, close enough for my fin to waft up a dense cloud of silt.

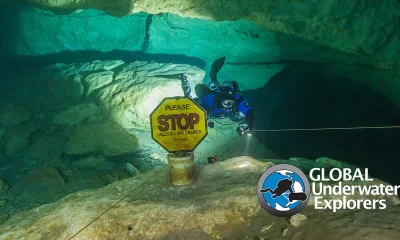

The fixed line—the only safe way out of this hole—is instantly obscured. Despite the fact that the passage is over 40 ft high, and the silt cloud only 10 ft, it somehow does not occur to me to “punch out” and regain my senses in the clear fluid at roof level.

The cloud is mesmerizing.

I try to signal Exley that I have lost the line, but use the wrong signal. | They interpret it to read that I am having a great time… And they signal back that they, too, are having a great time!

I can feel myself sliding towards the accretion disk at the edge of that psychological black hole called panic. By this time, Sheck has become aware that I am having some trouble. A hand drifts towards me, its open palm saying, “Come.” I grasp hold and we begin swimming. I am consciously aware that my heartbeat is picking up fast. The bubbles are crashing off in endless echoes, amplified tenfold like the resonant throbbing of a locomotive engine driving straight down every synapse in your being.

It is nearly impossible to concentrate. All visionary input is coming from the end of a long tunnel, the focal point of which is Exley’s hand, guiding the way out.

All at once, just as if someone had snapped their fingers, the tunnel vision is gone and the guideline is in my hand. The depth gauge registers slightly over 190 ft, barely 40 ft above where “something” had gone amiss. I reflexively check my air gauge then look towards Sheck—that mask and folded hands in solemn prayer, ever-floating in front of me—and signal, “I’m OK. You watch me?” He flashes the OK sign, following it with a thumbs up gesture.

We lift back into the tannic cloud and up through the hourglass. At 40 ft, we each pull out a set of “exceptional exposure” decompression tables and work through the numbers. It is going to be a long one. Now I know why we brought the paperback books.

By the time we hit the 10 ft stage, we have been underwater—and underground—over an hour and still have thirty minutes to go. Sheck opens the valve on the oxygen tank and passes the mouthpiece over to me. “Try this,” he pencils on his dive slate.

Pure oxygen, it turns out, greatly decreases the time a diver must spend decompressing, since it allows the dissolved nitrogen gas—the part that forms the bubbles which cause “the bends”—to be expelled twice as efficiently as when breathing compressed air. It has an odd metallic taste to it, and a thick texture, as if one were breathing some light liquid.

I begin reading a two-bit novel that Sheck has passed around along with the tube food. Not quite Saturday afternoon football, but it certainly beats staring at the rotting log I am straddling.

Soon enough, we punched out into the boiling afternoon air, none the worse for wear. Well, physically anyway. I could not help thinking about that blind corner at 71m/232 ft. I had come straight to the edge of the big gulp itself—would have stumbled into it were it not for the staying hand of my ever-watchful guide.

And it had come on so damn subtly.

I then had an intimate appreciation of the horror that must have enveloped John Shepard and Mike Trent, two inexperienced deep divers who had gone down that same booming borehole just two years ago, as they slid helplessly past those icy jaws. They had reached a point barely 100 ft further down the tunnel—at 260 ft—before going blank and staring at the wall until their tanks ran dry. Exley was eventually called in to make the recovery and, in fact, had given both of them their final lift out. The assist was, unfortunately, twelve hours too late.

Downright Religious

We optioned for a shallow dive the following day: a 884m/2,900 ft through-trip between two of the Peacock Springs entrances at a maximum depth of 18m/60 ft. The dive was thoroughly enjoyable, made all the more so by the opportunity to dive with Mary Ellen Eckhoff, Florida’s leading female cave diver. She was the one of that small fraternity that had actually packed their bags and moved to north Florida for the hot diving, and she was one hardcore lady.

Before I knew it, the dive was over and we were rushing to catch my plane. The situation was complicated somewhat in that the dive had required a small amount of decompression, and the manual recommended a 24-hour layover before flying. Since that was not possible, we drove down the interstate toward Jacksonville, me with the oxygen cylinder on my lap, breathing out of the regulator to reduce my residual nitrogen level. Several of the old folks we passed found the episode quite amusing.

As the plane sliced northward through the clouded sky, I knew that I had to go back there again soon. There was so much to learn yet.

Far from giving up after the Eagle’s Nest incident, I came to realize what the trip was actually all about: to scope out the edge of the envelope under controlled conditions and to begin to stretch it. Perhaps after a few years, I would understand it. I could certainly see its fascination. But what escaped me was what it felt like to finally reach that understanding.

While boarding the plane, I had finally popped the question: “Surely, you must feel something while deep diving, don’t you?”

“Why sure,” Sheck replied. “Sometimes it can be downright religious.”

“How’s that?” I queried.

“When you get real deep, you start to hear organ music,” he said, and suddenly burst into that hoarse, inhaling, strictly Exley laugh.

Return to the Sheck story package, “Revisiting the Legacy of Sheck Exley.“

DIVE DEEPER

InDepth: Remembering Dr. John Zumrick by Bill Stone

InDEPTH: Stoned: The Adventures of Wes Skiles and the US Deep Caving Team by Bill Stone

William C. “Bill” Stone, PhD, P.E. is the CEO of Stone Aerospace, Inc. and Sunfish, Inc., both based in Del Valle, TX. He is an internationally acclaimed cave explorer and the president of the United States Deep Caving Team.