Conservation

Take Only Ghost Nets, Leave Only Karst, rrr Coral? And What About the Water?

Four leading conservationists discuss the state of aquatic conservation and what can be done.

THE TALKS—Round Table Rhetoric with Stratis Kas

? Predive Clicklist: The Ocean by Led Zeppelin ??

With Nathalie Lasselin, Tom Morris, Pascal van Erp and Tali Vardi. Lead image: Pascal Van Erp during net lifting operation at a fish farm. Photo by Cor Kuyvenhoven

Ready to dive into the sharp edge of environmental urgency?

This episode of THE TALKS goes beyond polite cleanups and inspiring Instagram posts. We’re talking about entire ecosystems—fresh water sources, coral reefs, cave systems—teetering on the brink. A single abandoned fishing net can create a domino effect of destruction, and “out of sight, out of mind” could doom species we barely know.

Our roundtable of explorers, marine biologists, and ghost net hunters reveals a world where technology collides with ecology and where red tape can stall real solutions. They’ve seen it all: sunken fish farms-turned biodiversity traps, pristine caves scarred with a scooter’s flick, and corals fighting to survive in warming seas.

This isn’t yet another environmental plea—it’s a wake-up call for divers, scientists, and communities. If we don’t act, we risk losing more than mere scenery. We risk losing the health of our planet and, ultimately, ourselves.

Welcome to a new frontier of responsibility and possibility.

This is THE TALKS Episode #8.

KAS: Today, I’m joined by a remarkable panel of experts, each with a front-row seat to the hidden realities beneath the surface. As the world’s environmental challenges escalate, conversations around conservation have never been more urgent. Divers and scientists alike are discovering how our impact on underwater ecosystems is far greater than we realize, and it’s time we address these issues more frequently and more openly.

Before we begin, let’s acknowledge that protecting our planet isn’t just a noble idea—it’s become an everyday necessity. The cost of inaction grows by the day. Our roundtable today aims to shine a light on the unseen struggles and overlooked victories that define aquatic conservation efforts worldwide.

With that in mind, I’d like to start with a direct question to our guests: What you see, we don’t see. As individuals deeply embedded in underwater ecosystems, what are you witnessing in our oceans, caves, and waterways that most divers—and even the broader public—remain blind to?

TOM: Cave diving has gotten really popular here in Florida. There are so many more divers than there used to be and a lot of instructors pushing people through courses. But I’m seeing far too much unnecessary damage in the caves. As a community, the Cave Diving Section has fallen down on the job of teaching new divers about cave conservation. I used to be the conservation chairman, and I realized the best place to instill a conservation ethic is during instruction. New divers really listen to their instructors. That’s the perfect time to teach them about proper skills, attitude, and what they can and can’t touch in a cave. For example, I was gearing up one day, and a new diver with a rebreather was about to go into a cave. I mentioned goethite, a mineral that forms in caves, and he said, “What’s goethite?” I couldn’t believe his instructor let him out of class without knowing what it was. Goethite is delicate and takes tens of thousands of years to form. If you don’t even know it’s there, how are you supposed to protect it?

But the biggest danger to our caves isn’t divers—it’s what’s happening above ground. Florida’s aquifer is one of the best in the world, but we’re over-pumping it. Most springs have lost about 20% of their flow since the 1980s, and nitrate pollution is everywhere. While nitrates don’t affect the caves directly, when the water comes out of the springs and hits sunlight, it grows nuisance algae. This is a landscape-level problem, and it’s going to take government action to fix it. But right now, the government here in Florida is falling down on the job.

TALI: With tropical coral reefs, which make up a big part of the recreational dive community’s experience, we’ve lost about 50% of them since the 1950s. That’s an entire ecosystem that’s been halved. The problem is that most recreational divers don’t see this loss. Tourists go to a dive shop in a beautiful location and are taken to reefs that still look good because the loss is so patchy. Some reefs remain healthy while others are completely degraded. So, for a recreational diver, it’s very hard to see the bigger picture on a regional scale, let alone the global scale. That’s where science plays a really useful role—to help paint those global pictures.

There’s also a time perspective to this. Every year, more divers are being trained, but coral reefs have been declining steadily—about 7% per decade in certain regions. That loss happens slowly over time: with big mass bleaching events along the way, but also due to inadequate environmental protections. A new diver might look at a reef and think, “Wow, this is incredible! I’m underwater, I’m breathing, I’m seeing these tropical fish!” But they have no way of knowing what that reef looked like 10 or 20 years ago.

That’s the concept of shifting baselines. Each new generation of divers only sees what’s left today, not what’s already been lost. It’s hard to communicate that without ruining someone’s excitement or love for diving. You don’t want to discourage them, but you also want them to understand that coral reefs are incredibly sensitive ecosystems. They’re not just beautiful—they support biodiversity, provide food, protect coastlines, and more.

The good news is that the newer generation of divers is showing a lot more interest in conservation, and even restoration. Dive shops and the tropical reef diving industry are starting to embrace this shift, but there’s still a long way to go. I really appreciate the question because it highlights just how much we see that others don’t. And that awareness is such an important first step.

NATHALIE: One thing that always crosses my mind is, What’s the most important element—the thing I can see, or the thing nobody can see? I’m talking about emerging contaminants, for example. Even though I do a lot of cave diving and other activities here in Montreal, I’m especially concerned about the source of our drinking water—our fresh water. There’s a lot happening with different kinds of pollution, from invasive species to emerging contaminants like pesticides, herbicides, and drugs. It’s hard to make people aware of the impact each dive can have, or what might be carried on our equipment from one body of water to another. That means every diver needs to be educated about the things we can’t see, even if we’re paying close attention.

On top of that, we need to figure out how to change our behavior to protect and preserve the environments where we dive. I’m sure, Tali, it’s the same in your area—thinking about what you put on your skin, for instance. Conservation goes far beyond just the cleanups we do. It’s relatively simple when the problem is visible, but it’s much harder when you can’t see it. That’s why taking good actions to lower our impact is so crucial.

PASCAL: As most of you probably know, our focus is water pollution, especially lost fishing gear. In many of my presentations, I point out that just because the public doesn’t see something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. For instance, I’ll show a sunrise or sunset over the ocean, and non-divers see a beautiful scene—everything looks perfect. But under the surface, there’s a lot going on. That’s what divers notice.

It’s fascinating that we’ll go to certain areas—even diving centers with instructors who’ve been there 25 years—and they don’t see the problem at all. I remember once in Malta, we told a diving center owner we were looking for lost fishing gear. He said, “Good luck. There’s no lost fishing gear here. Actually, now that you mention it, there’s no fish either.” So, we went diving with him, and on our very first dive we found hundreds of meters of lost long lines and gill nets in places he visits almost daily. It’s remarkable how many people miss it—maybe because they’re not looking, or they don’t recognize what they’re seeing. I’m not entirely sure why, but it’s interesting how many divers overlook these things. I hear it again and again from people’s stories.

KAS: Tom, can you share a defining moment in your career that profoundly shifted your understanding of how humans affect underwater ecosystems?

TOM: The first thing that comes to mind is a cave just 30 miles from my house called Devil’s Eye. It’s a world-class cave dive, and I mentioned goethite before, the mineral that forms different structures inside caves. By the way, it’s named after Goethe—the philosopher, scientist, writer. Before underwater scooters, you had to swim a long way against a strong current to reach some parts of the cave. In one passage, there are these goethite plates on the floor—each as big as a trash can lid—and they’re just beautiful, tilted at different angles. Once scooters came along, almost anyone could reach that spot. I remember taking a scooter back there and seeing several of those plates flipped upside down, ripped out of the floor. I imagine someone had a regulator dangling, and it snagged one of them, jerking it up. That really blew my mind.

I actually own a cave myself, and I’ve done a good job of limiting traffic. Beyond a certain level of traffic, damage becomes almost inevitable. So, I’m very careful about who I let in, and I’ve owned it for about 25 years now. By keeping the traffic low and being selective, it’s still in pristine condition. I’ve been cave diving for over 50 years, so I remember seeing many caves in absolutely pristine condition. Now, when I notice damage, it really disturbs me. New divers may not realize what it used to look like—that’s the shifting baseline phenomenon in action. It’s a real issue, both underwater and on the surface.

KAS: You’re lucky to have your own cave—I wish I could say the same. Thank you for preserving it. Biodiversity in caves isn’t a widely discussed topic. What’s your perspective on it?

TOM: The southeastern United States is the world’s biodiversity hotspot for crayfish, and 17 of those 65 species are troglobites—they live in caves. We’ve even spotted a couple more that we’re still trying to formally identify. Once you get into it, it becomes more and more fascinating. There are still plenty of mysteries in caves—the hydrology, the biology, the sedimentology, and so on.

KAS: Nathalie, let’s talk about diving as advocacy. Diving puts us on the front lines of environmental degradation. So why do you think technical divers, despite being so close to these vulnerable ecosystems, often show limited engagement in conservation efforts?

NATHALIE: I think today’s technical divers are nothing like they were 10 or 20 years ago. A lot of them spend tons of time perfecting their trim and making sure their hoses are the right length—really focusing on technique and equipment. When we do cleanups, we often deal with zero visibility, and it’s solo diving, so I need divers with technical skills. Yet most of them, at first, aren’t interested because it doesn’t seem like it offers any personal reward. It doesn’t feel like an achievement, you know? They wonder, “What am I going to see? Is there a new wreck or something cool?” At first, it’s hard for them to see the appeal. But once they start doing cleanups—spending hours cutting away rubber, freeing tires, really using their buoyancy skills—they begin to understand the value and the enjoyment of that kind of dive. Environmental cleanups, taking samples, or even documenting an area’s changes makes divers feel part of a team or a larger project. Their mindset shifts from “I want to be an elite tech diver” to realizing, “I can use the skills I’ve worked so hard to develop for something meaningful—for the community.” It’s about showing them how their abilities can be used. Once they see that, it’s easier to find volunteers for cleanups or other commitments.

TOM: I’ve criticized some of the things cave divers do, but I also have to give them credit. We’ve had several cases where they really stepped up and helped conservation efforts. For instance, there was a plan to build a tank farm for storing petroleum products with multiple pipelines converging in a super sensitive area. Three separate streams go underground there, traveling something like 27 km/17 miles before resurfacing at a spring—an oil spill would’ve been a disaster. But a cave diver named Chris Brown took the lead and, in the end, they moved that tank farm somewhere else entirely. It was a big win for the environment.

Recently, our cave diving group has focused on a place called Alachua Sink, which the Cave Diving Section actually owns. A big housing development is planned in the valley upstream. The cave divers have done a great job of alerting county commissioners and everyone affected so we can get oversight and minimize environmental impact. That’s another example of cave divers stepping up in a conservation role.

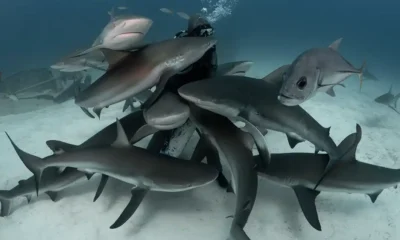

PASCAL: At Ghost Diving, we say technical diving is just the starting point for conservation diving. Anyone can pick up a piece of plastic or line, which is still helpful. But complicated projects, like lifting an entire fish farm or multiple tons of nets, require divers who are really drilled in multitasking—people who can function in zero visibility, remain safe, and still get the job done.

KAS: Let’s define the diver’s role. What unique responsibilities do divers have in conservation compared to people who work on land-based environmental issues? How does this direct interaction with aquatic ecosystems shape that responsibility?

TALI: Worldwide PADI has issued 29 million diver certifications since its inception, according to my colleagues at PADI. When it comes to my main focus—coral reefs and their restoration—these divers are vital advocates. Coral reefs protect coastal communities by reducing the energy of storm waves by up to 98%. These reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor but support and safeguard hundreds of millions of humans.You can’t conserve what you don’t know, and you can’t truly know an ecosystem unless you see it for yourself. Diving offers a window into an underwater world that’s incredibly important. It’s simply easier to convey the need for reef preservation to a diver who’s experienced it firsthand than to someone who’s never been underwater.

In the past, many divers only wanted to see pretty reefs, but as reef health has declined over the years, people have become more interested in fixing them—whether it’s in their own backyard or on a large scale like the Great Barrier Reef, where hundreds of millions of dollars are being invested in reef restoration and adaptation. My organization, the Coral Restoration Consortium, has been developing a collaboration with PADI Aware Reef-World (which manages the Green Fins program) to capture the spirit Nathalie mentioned: deepening how divers engage.

Divers are already advocates, but more of them want to take a direct, active role in restoration. We want to build on that enthusiasm and help dive operators develop reef restoration programs. This is a new kind of diving that’s emerging—tropical dives specifically aimed at restoring coral reefs. Our goal is to guide dive centers toward the most impactful methods so these restoration efforts achieve real, lasting results. Because restoration diving is active rather than observational—like learning a new dance instead of watching someone else perform—it feels good to take a physical step and truly connect with this magical ecosystem.

PASCAL: Mario Arena from SDSS has been searching for lost battle fleets in the central Mediterranean for over 20 years—things like WWII convoy ships sunk in battles such as the Battle of Pantelleria and the Battle of Convoys. He invited me to check out the nets getting in his way of identifying these shipwrecks. Of course, hearing “nets” got my attention! So we went out. People pay a lot of money to dive these historical wrecks—the WWII graves, ships from famous battles. Mario was so enthusiastic.

We went down to a shipwreck at about 60 m/200 ft, all on scooters. As soon as we descended, Mario zoomed off to explore the superstructure. Meanwhile, I spotted a huge tuna net right where our anchor dropped. I stayed put in about a 50 m2/538 ft2 area, working on that net. After half an hour, Mario came back looking for us. He was like, “What are you guys doing?” I said, “There’s a net here—it needs to come up.” So we started cutting it away.

When we surfaced, he told us, “You guys are nuts! You see a net and stop everything? Do you realize how much history is down there? This is a huge wreck—I had so much to show you!” He’s Italian, so of course it was a bit dramatic in a funny way. But I explained we had a goal: remove the net. Everyone has their own priorities.

It made me think, “Yeah, maybe I should have taken one dive just to look around and appreciate the wreck.” There’s amazing history down there. Next time, maybe I’ll do a sightseeing pass before cutting out nets!

TOM: Tali, it’s great to hear about divers getting involved in coral restoration and how you’re bringing dive boat operators on board. When you first start diving, you focus on survival and gear. But once you’re comfortable, you want something more—like photography. In caves, some divers get into biology and run long-term surveys, making real contributions without being formal scientists.

TALI: Some divers just want to see how deep they can go, and that’s their only focus. We want to help channel that enthusiasm into something meaningful. After all, if people crave new achievements, why not guide them toward conservation? Even a simple certificate after each dive could keep them motivated.

NATHALIE: Many technical divers love feeling part of a team—that sense of belonging is really strong. So whenever we plan a cleanup or project, we focus on making them feel they’re part of something special. It’s also a great way to encourage local diving. As long as weather permits, they can dive nearby and practice their skills without traveling far. They learn to multitask and discover new kinds of dives—like cutting submerged trees in the Manicouagan Reservoir. It’s a unique way to do something meaningful together.

PASCAL: Technical divers really crave belonging, and we use that to our advantage. Ghost Diving has become a brand people want to be part of; we’re in 16 countries now without ever recruiting anyone.

That’s great for growing awareness, but there’s a downside too. When you’re on limited time underwater, it can feel like a gold rush. You focus so hard on the task, you risk forgetting safety. That’s why we train our teams to watch out for each other. I fall into that trap myself—when I’m close to freeing a net, I might think, “I can push five more minutes…maybe ten?” Then I see my teammates asking if I’m sure. We all need to remember not to let the job become dangerous.

KAS: Tom, in your experience as a biologist and cave diver, how should divers handle the ethical challenges of exploring sensitive or uncharted ecosystems? Should stricter codes of conduct be introduced to protect these areas?

TOM: My top priority is never damaging the cave. If exploring deeper requires extra tanks that might harm the environment, I’ll stop rather than risk scarring it. I believe conservation ethics should be ingrained during cave diving classes. Students look up to their instructors, so teaching safety, exploration, and conservation together is crucial. To protect sensitive caves, divers need three things: knowledge of how the cave works, the skills to avoid harming it, and the right attitude toward conservation. Missing any one of those will eventually lead to damage.

KAS: These days, we have gear that allows deeper, longer, and more precise dives. How do you see these advancements being used for conservation instead of just exploration?

NATHALIE: I believe all these new tools—including something as simple as modern dive computers that track decompression more accurately—can make a real difference, especially when you’re working alone in zero visibility. Yet it’s funny how the actual cleanup work still relies on very basic tools—things like a knife or a lift bag, which have existed forever. These are the main implements we use to remove debris or take samples.

There’s also a regulatory side to consider. In some places, you can’t perform certain tasks or use specific tools unless you’re a certified scientific or commercial diver. Even if it might be safer or more efficient to use battery-powered cutting tools, as technical divers we might be restricted by liability and legal requirements. So we end up sticking to simpler gear, like using a standard commercial diver’s knife to cut tires. That’s just the reality of the legislation in some areas.

KAS: I hadn’t realized how legislation could limit you from using certain tools, especially if they make the job easier or safer. Hopefully, regulations will evolve so that divers can leverage the latest technology to better protect our underwater environments.

PASCAL: In our case, using rebreathers at depth actually helps reduce helium costs. This means we can stretch our budget further and put our funding and donations to better use. So in a roundabout way, rebreathers do support conservation by keeping project expenses manageable.

TOM: It’s interesting how certain technologies can be a double-edged sword when it comes to cave conservation. Take underwater scooters, for instance. In high-outflow caves, before scooters became popular, divers had to pull themselves along the walls or crawl on the bottom—what we called “groveling.” In caves with sandy bottoms, that damage would heal quickly in the current, but in rockier areas, it could scar the cave. Now, with scooters, divers can zip through without touching anything—provided they have the skill and the right attitude. Otherwise, they risk doing more harm than good.

PASCAL: Right. In our work, scooters have essentially become standard equipment. Efficiency is the biggest reason: If I’m diving deep, I don’t want to spend forever swimming to the site. I’d rather get there quickly, do what I need to do, and head back. Sometimes we also use scooters to drag nets behind us, especially if we can’t safely shoot them to the surface—like under busy ferry lines, where we had to tow everything to the shore before lifting it out.

KAS: Tali, when reefs face bleaching or extreme weather, how can dive operators adapt to minimize damage while still running a business?

TALI: I’d first note that some dive operators are already adapting. For instance, in Thailand, certain reefs are closed off when a mass bleaching event is predicted. We’re pretty good at forecasting bleaching now—NOAA Coral Reef Watch models are incredibly accurate. So, if you know a bleaching event is imminent, one way to help corals is to reduce diver traffic, especially newer divers who may kick up sand or inadvertently damage fragile areas. This step is small, but potentially quite impactful.

The challenge is making such closures more systematic. The predictions we have right now often cover a broad area—say, a 20-km/12-mile region. Meanwhile, individual dive operators work at a smaller scale, so they might not know which specific reef will be hardest hit. That’s where we need more precise, localized climate and oceanographic models—something that typically requires funding and expertise most dive shops don’t have.

We can also think creatively. If a dive operator knows a bleaching event is on the horizon, maybe instead of visiting a vulnerable reef, they can offer an alternative experience—working in a coral nursery, exploring a seagrass bed in search of turtles, or something else that’s less risky. That way, they’re not harming the reef, but they’re also still giving guests a memorable activity.

KAS: That makes perfect sense. But what about formalizing this approach? Should there be some kind of official initiative or part of standard diving training that emphasizes responsible tourism—maybe even mandatory courses?

TALI: I agree there’s room for that. So many courses already exist for advanced certifications, but they vary in relevance. Integrating sustainability and conservation best practices as a required module—both in theory and in practical skills—would be hugely beneficial. It would teach new divers from the start how their actions affect the reef and how they can minimize their impact, or even participate in restoration. That could really help change the industry culture and better protect these ecosystems we all value so much.

Having an obligatory conservation module for Dive Masters—teaching them how to select sites based on bleaching forecasts—would be a simple, meaningful step. NOAA’s global bleaching predictions [Coral Reef Watch] are user-friendly. If Dive Masters considered them, it could help reduce stress on reefs at critical times. Of course, coral bleaching has many factors, but raising awareness at the Dive Master level could make a difference. Also, Dive Masters in general deserve a shout-out. They have the deepest daily knowledge of local reefs and serve as incredible advocates for coral conservation.

KAS: Let’s talk about redefining adventure in technical diving. How can we keep the thrill of exploration while emphasizing protection rather than just discovery?

PASCAL: For me, the work we do still has a lot of exploration and adventure—mainly because pollution can be found everywhere. We also seek out “eye-catching” projects in fascinating places: spots where no one would normally dive. For instance, in Greece we’re dealing with “ghost farms,” abandoned fish farms left submerged or partially active. These sites often attract marine life due to the leftover feed, so they’re full of biodiversity, especially around the seagrass meadows. Yet most divers never go there, so even though it’s polluted, exploring it feels thrilling. My “adventure heart” starts racing when I’m scouting these areas, discovering creatures and environments I’ve never seen before.

TOM: This reminds me of a personal project. Just a few miles from my house, there’s a place called Alachua Sink—a huge marsh that drains into a sinkhole. A biologist friend told me it was crystal clear, which was a bit of an exaggeration, but we went anyway. The sinkhole is about 20 m/65 ft across and was loaded with alligators—maybe 30 of them, around six feet long. The three of us spent an hour and a half watching them, making sure none were massive. Then we dove in.

Office secretaries came out to see if we’d get eaten, but the gators weren’t interested. We did see their tracks—footprints and tail drags—down at 20 m/65 ft. It got me thinking about how many gators enter these caves and never find their way out, kind of like untrained divers. I’ve started recording how deep they go. Right now, my record is 44 m/145 ft—there’s a skeleton down there in a spot where it definitely didn’t just drift. This is a little “adventure meets science” project for me—pure exploration coupled with data-gathering, and another way to stay curious and connected to the environment.

TALI: This might sound like a nerdy question, but it could be really useful for the article—either for Pascal or anyone who knows. We see this issue in reef restoration, too: If a restoration project fails, people sometimes just abandon it. That’s something we stress a lot right now as we lay out guidelines for starting a restoration program. You have to remove any physical structure you put in the water if the project is abandoned. You’d think there would be some permitting agency to prevent fish farms from being abandoned—someone who’d say, “You can’t just leave everything behind in the ocean. You must remove the structures.” But is that not the case? Or do the laws exist, yet people abandon fish farms anyway?

PASCAL: It seems like a straightforward question with a simple answer: “Of course you can’t abandon your fish farm.” In many Western European countries—like the Netherlands, the UK, or Germany—you’d face severe penalties. You might even go to jail, and you’d still have to pay the cleanup costs. But not in Greece. Don’t ask me why, but there are all these overlapping laws and property rights that let owners leave things behind if it’s on their land. Nobody can legally touch it without their permission, no matter how much it’s leaking into the environment. It’s a complicated subject that even our organization’s lawyers are struggling with. “Ghost farms” are a real problem here.

A recent example: There was an abandoned fish farm on the Western mainland of Greece that had become a complete eyesore—rings, pipes, nets strewn everywhere. The beach couldn’t be used, and the pollution was awful. The owner didn’t care. Nobody could reach him, and no one could legally force him to remove the debris. We finally raised donations and sponsors, went in, and cleaned it up. Then, a couple of weeks later, the police called us, saying the owner claimed we had stolen his fish farm.

TOM: Here in the US, some caves have been blocked off by authorities or landowners when divers died in them. For instance, at Morrison Springs there was a big room with a deep crack at the bottom; after a few drownings, the Sheriff’s Department used dynamite to seal the entrance so divers couldn’t get back there. We know of other “killer caves” that were blasted or filled with rubble to prevent further accidents. In Florida’s past, farmers also treated sinkholes like convenient dumpsters, tossing in old fences, 55-gallon pesticide drums, and other trash. We still find a lot of that debris in sinkholes, but luckily people are becoming more educated, so it doesn’t happen as often.

KAS: Nathalie, a direct message to the industry: dive boat operators, cave property or environment owners, training agencies, and divers themselves. What would you say about everyone’s collective role in protecting the environment?

NATHALIE: As divers—especially technical divers—we’re privileged witnesses to more than 70% of the planet, yet we’re such a small percentage of the world’s population. Because we can enter these environments, the least we can do is care for them. Even if we’re not responsible for past pollution or the mistakes of fishermen or industry, we do have the power to be part of the solution. And it doesn’t have to be heavy or difficult—it can be fun. Beyond just enjoying the view and taking pictures, we can act as real sentinels, helping and protecting these places.

TOM: Speaking of taking pictures, that’s a big part of it—bringing the beauty back to the surface. When I worked with Wes [Skiles] on documentary films about cave diving, we always wove in a conservation message. He called it “edutainment,” educating and entertaining at the same time. It feels good to include that message in everything we share.

PASCAL: In our work removing lost fishing gear from the oceans, we say that if we don’t bring back photos or videos, it’s like it never happened. Yes, we’re making a localized difference, but there’s so much lost gear out there, and more is added every year. Our bigger mission is raising awareness, so we document everything—no dive without a scooter, and no dive without a GoPro.

KAS: I wholeheartedly agree. Exploration or conservation work isn’t complete unless it’s shared. Even if you’re just making a small difference, showing those results can spark momentum and inspire more people. Thanks to modern technology, it doesn’t take much time or money, and it doesn’t add much task-loading. Sharing is essential to making any effort truly impactful.

Tali, coral reefs are often described as “noisy” ecosystems, yet we’re silencing them through damage. What would you say to divers about their role in either muting or amplifying these underwater voices?

TALI: I think you have to be careful with the “noise analogy.” Sometimes even on a nearly dead reef, you’ll still hear snapping shrimp in the rocks, munching on microalgae or turf algae. So I see your question as more metaphorical. For reefs, I focus on the bleaching aspect: You have these vivid, unbelievable colors everywhere, and then it all goes white.

To any diver who loves coral reefs, I’d say: Use that passion to show the world how valuable and fragile they are—especially as they face the looming threat of climate change. Climate change is a silent killer of reefs. Yes, you can see anchor damage or fishing gear damage, but carbon emissions—mostly from developed countries like mine—are heating the oceans on a global scale. Reefs are on a razor-thin threshold; we’ve already passed the 1.5° C/37.4 °F warming mark, which puts reefs in real jeopardy of permanent collapse. Right now, we’re trying to preserve coral genetics so we can rebuild reefs in the future—if the ocean ever stabilizes or cools a bit. That’s the reality of where reefs stand today, and I think it’s crucial for every diver interested in coral ecosystems to grasp just how serious the situation is.

TOM: Is there any evidence that coral reefs are shifting northward or into cooler waters?

TALI: There is some evidence of poleward movement, but it’s incremental. When corals move north, they run into new issues: increased turbidity, changes in sunlight, and differences in the lunar and solar cycles that affect reproduction. Nothing about these shifts should make us feel okay about what’s happening in the tropics—the pace of warming is too fast. It’s why our restoration community, including my group, is increasingly focused on things like cryopreserving coral genetic material. We never thought we’d have to do it so soon, but we want to protect as much genetic diversity as possible for a future where oceans might be more stable.

TOM: Are corals suitable for cryopreservation?

TALI: Yes, there’s been a lot of progress. We can cryopreserve coral sperm pretty easily, and we’ve shown proof of concept by fertilizing eggs of multiple species. It’s still a specialized and somewhat costly technology, but we’re trying to “democratize” it—at least enough to store coral genetics safely.

TOM: As you mentioned earlier, so much of the underwater world is out of sight, out of mind—this isn’t just true for oceans but also for freshwater habitats. Here in North America, the creatures hit hardest by extinction are gastropods like mussels and snails. Their die-off rates are way higher than any other group of animals. We barely notice because it’s happening underwater, where most people never look.

KAS: Here’s the big question for everyone: What is the cost of our inaction?

NATHALIE: For me, focusing on freshwater, the cost of inaction is our own health. If our drinking water sources become more polluted because of the way we produce food, or how we treat waste, that directly impacts our well-being. We can’t just “save the planet” as a vague concept, but we can make sure our communities stay healthier by preserving the water sources around us. It’s not always straightforward. For instance, cleaning up debris in the St. Lawrence River requires permits so we don’t harm endangered native mussels or disturb delicate ecosystems already at risk from invasive species. The complexity of these environments keeps growing. But we can’t simply wait and see. We need to involve more people and show them it can be fun and fulfilling to make a difference regularly, not just once a year.

TOM: Globally, I’m worried about climate change—especially coral reefs. Locally, in Florida, over-pumping our aquifers is a major concern. When a spring stops flowing, the water in the cave stagnates, and oxygen levels can drop too low for cave life to survive. We’ve seen mass die-offs. Pollution is another wildcard: The data is mixed, but nitrates from agriculture can hurt cave organisms. I admit to being a bit pessimistic, but maybe that pessimism can spur action.

TALI: We’re already seeing the cost of inaction on coral reefs. About 50% of reefs are gone, and entire island cultures are threatened as sea level rise forces relocations. For many Pacific communities, corals are the source of life, tied to their origin stories. Meanwhile, reefs protect coastlines and support a quarter of all marine biodiversity. The losses are incalculable.

On the bright side, the coral restoration field is growing rapidly. We just held a conference with nearly a thousand attendees, filled with energy and innovation. But climate change looms over it all—if global temperatures keep rising, we’re racing to preserve genetic material through cryopreservation so that, if things stabilize, we can potentially reintroduce corals in the future. There’s a huge global effort here, but we need more movement on carbon emissions to make a real difference.

PASCAL: With lost fishing gear, inaction leads to a vicious cycle: Nets keep catching marine life, which then attracts scavengers and more animals, causing ongoing destruction of habitats and further decline in fish stocks. Over time, these nets degrade into microplastics, poisoning our own food chain. We also face tricky situations: Sometimes ropes left on the seabed develop coral colonies or serve as anchor points for shark egg capsules. In those cases, removing everything could do more harm than good. So we have to balance cleanup with an understanding of each site’s ecology.

KAS: Thank you all for sharing these final thoughts. It’s clear the cost of doing nothing is enormous—whether it’s drinking water contamination, cave life die-offs, coral reef collapse, or persistent ghost nets in our oceans. Yet each of you is showing that action, however complex and challenging, is still possible and worthwhile. May your stories motivate divers and non-divers alike to join in and help protect our precious underwater worlds.

Nathalie Lasselin

Underwater Cinematographer, Explorer, and Environmental Advocate

Nathalie Lasselin, a distinguished Canadian underwater cinematographer, explorer and environmental advocate, is renowned for her expertise in capturing breathtaking underwater visuals in some of the most demanding and harsh environments. Her portfolio includes a diverse array of underwater projects, spanning documentaries, expeditions, and scientific research. Fueled by an unwavering passion for the underwater realm, Lasselin has undertaken exploration and documentation endeavors across a spectrum of ecosystems, from the Arctic to underwater caves and shipwrecks in dark deep waters. Her collaborative efforts with scientists, researchers, and filmmakers serve as a powerful means to spotlight environmental concerns and advance the cause of ocean conservation. Kids 8 years old study her in their school book in Quebec. She was the first to dive and film several places including deep wreck in the St Lawrence river in Canada, caves in China, the 4th biggest crater lake and dove 70 kms in the river in Montreal to raise awareness towards out drinking water source. She is an inductee of the WDHOF ( Women Divers hall of Fame) the Explorers club, the RCGS (Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

Links

Aqua Sub terra Explorations:www.aquasubterra.org

Personal website: https://aquanath.com/

Tom Morris

Underwater Explorer, Filmmaker, Author, and Advocate

Tom Morris is an ecologist with degrees in Wildlife Biology and Botany. He grew up swimming and diving in Florida’s springs since about 1960, and has witnessed the general decline in their health. His cave diving hobby blended nicely with his biological career, and he considers himself lucky to have been able to explore and study what were the almost entirely undescribed groundwater ecosystems in Florida and, to a lesser degree, Mexico. Tom has a background in water resource studies, having worked at Florida’s St. John’s River Water Management District and the Center for Wetlands Research at the University of Florida. He worked for several decades at Karst Environmental Services, a small company specializing in groundwater and biological resource studies. In the early 80’s Tom started diving with Wes Skiles and they became lifelong diving partners.Tom got to join Wes on his filmmaking career, and helped film many documentaries, including an IMAX film and National Geographic and NOVA specials, involving springs and caves in several countries, which always emphasized the protection of natural resources. Karst Environmental Resources has recently shut down, but Tom continues his studies of Florida’s groundwater ecosystems, focusing on its rich troglobitic fauna.

Pascal van Erp

Founder & Chairman Ghost Diving

With a deep passion for marine conservation, Pascal has become a leading figure in the fight against marine pollution, particularly in addressing the global issue of “ghost fishing.” As a CCR/technical diver specialized in marine pollution, Pascal has been at the forefront of underwater clean-up efforts since 2007, dedicating his diving skills exclusively to protecting the environment. In 2012, Pascal founded Ghost Diving, a globally recognized organization that encourages divers to actively participate in underwater clean-up efforts while prioritizing safety. His team-oriented and standardized approach to conservation diving has significantly influenced the sector, making him a respected name in the field. Pascal’s expertise and dedication have led him to spearhead numerous research and clean-up projects targeting lost fishing gear across the world’s oceans. As a result, he is frequently invited to share his insights as an expert in various international forums and public discussions.

Organsation:

https://www.facebook.com/ghostdiving

https://www.linkedin.com/company/ghostdiving

https://www.instagram.com/ghostdivingorg

https://www.threads.net/@ghostdivingorg

https://www.youtube.com/@ghostdivingorg

Personal:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/pascalvanerp

https://www.instagram.com/suberp

https://www.facebook.com/suberp

https://www.threads.net/@suberp

Dr. Tali Vardi

Executive Director of the Coral Restoration Consortium (CRC)

Dr. Tali Vardi is the Executive Director of the Coral Restoration Consortium (CRC), a global community of practice. Since 2017 the CRC has been connecting coral reef restoration practitioners, scientists, and managers to provide best practice guidelines, host the Reef Futures symposium, and foster regional collaboration. Tali brings 25 years of experience and has authored over 20 publications in the fields of habitat restoration, coral reef ecology and intervention science, as well as international policy, advocacy, and community building. Tali co-chairs the International Coral Reef Initiative’s ad hoc committee on Reef Restoration, is the Chair of the International Coral Reef Society’s Chapter on Restoration, and serves on the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Coral R&D Accelerator Platform. She has been at the center of the coral restoration movement for over a decade, co-founding the CRC during her 11 years as a coral scientist at NOAA. She earned her PhD from Scripps Institution of Oceanography and her Bachelor’s and Master’s Degrees from the University of Pennsylvania. Tali started her career in New York City -working with the Parks Departments’ Natural Resources Group in wetland and forest restoration and grant writing. Tali is a mom, swimmer, Rescue Diver, big laugher, and has recently started learning how to harmonize Bluegrass music.

LINKS

https://www.linkedin.com/company/coral-restoration-consortium/

Stratis Kas, a Greek-Italian professional diving instructor, photographer, film director, and author, has spent over a decade as an esteemed Advanced Cave instructor, leading expeditions to extreme locations worldwide. His impressive diving achievements have solidified his expertise in the field. In 2020, Kas published the influential book Close Calls, followed by his highly acclaimed second book, CAVE DIVING: Everything You Always Wanted to Know, released in 2023. Accessible on stratiskas.com, this comprehensive guide has become a go-to resource for cave diving enthusiasts. Kas’s directorial ventures include the documentary “Amphitrite” (2017), shortlisted for the Short to the Point Film Festival, and “Infinite Liquid” (2019), which explores Greece’s uncharted cave diving destinations and was selected for presentation at TEKDive USA. Kas’s expertise has led to invitations as a speaker at prestigious conferences including Eurotek UK, TEKDive Europe and USA, Tec Expo, and Euditek. For more information about his work and publications, visit stratiskas.com.