Community

Take Only Pictures, Leave At Most Bubbles? The Case for Wreck Preservation

Should artifacts be removed and recovered from shipwrecks, or should our underwater cultural heritage be left undisturbed? Regardless of what your choice is,, under which circumstances? These are the questions that Finnish CMAS instructor, and scientific diver Rupert Simon seeks to answer based on directives from UNESCO’s 2001 Convention along with several governments and training agencies.

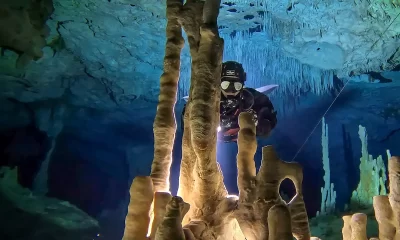

Text and photos by Rupert Simon unless noted. Header image: Anchor of Plussa in front of the maritime museum in Mariehamn, Åland, Finland.

“Underwater cultural heritage” means all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical, or archaeological character which have been partially or totally underwater, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years…” UNESCO 2001 Convention, Art. 1 para. 1(a)

Many years back, a fellow diver proudly showed me an amphorae (likely Roman) he had salvaged from a wreck in the Mediterranean Sea. Relatively recently, I watched a video in which a diver brings up an intact porthole from the bottom of the Baltic. Last December, I saw photos in a scuba blog that showed divers presenting their trophies—amongst them was a self-described “… avid collector of shipwreck artifacts.” These examples show that collecting artifacts from shipwrecks, which are de-facto archaeological sites of cultural heritage, is still common. I can’t help but wonder how the habit of collecting items from wrecks for personal benefit applies to the preservation goals taught throughout all main international scuba diving certification bodies.

As an example, Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) states on its webpage that, “Exploring, observing, and documenting the underwater environment is critical to protecting it from threats, deliberate or inadvertent, and thereby helping conserve our aquatic heritage for future generations.”

Also, the World Confederation of Underwater Activities (CMAS) demands, “Respect for Environment and Cultural Heritage,” and, “Commercial or personal interests do not justify negatively affecting the environment or the underwater cultural heritage sites.” Of course, the education and certification bodies are not responsible for the actions of the diver once certified—we are. When reminding treasure-hunters that we were asked not to touch anything while in training, a response like “There are so many and these few don’t really matter,” or “They’ve been there for such a long time, and no one really bothered to take care of them,” seems logical. However, this perception does not withstand the reality check described below. So, what’s the problem?

The Problem

Removing artefacts interferes with archaeological research

Archaeologists and other scientists study wreck sites to gain information about the lives of our ancestors. When we remove artefacts from their contexts, some information goes with them. But, even more information is lost without the context—the exact place where the item was in relation to other artefacts or the whole site. Therefore, archaeologists document their work meticulously. On top of that, the treasure hunter may have chosen the one item that carries critical information that leads to the identification, dating or historical context of the whole site.

A good example is the recent excavations on the Gribshunden wreck in Sweden. One of the first items recovered was the figurehead—”the monster”—which probably would be a tempting trophy. Leaving aside the cumbersome conservation required for such artifact, the identification of the wreck would have been much more difficult without it. Niklas Erikson explained the situation at the site in 2015 and, during the discussion, the experts were worried that even a careful scientific excavation using paint brushes to keep details intact would tamper with the find (see the documentary “The Ship That Changed the World,” 2021). How much worse is the impact on such a site when taking items from a wreck with a treasure hunter approach, without considering the impact on other artefacts? Divers randomly retrieving artefacts from sunken ships do interfere with the work of archaeologists, experts, and museums collecting information for the common good.

Impact on Other Divers

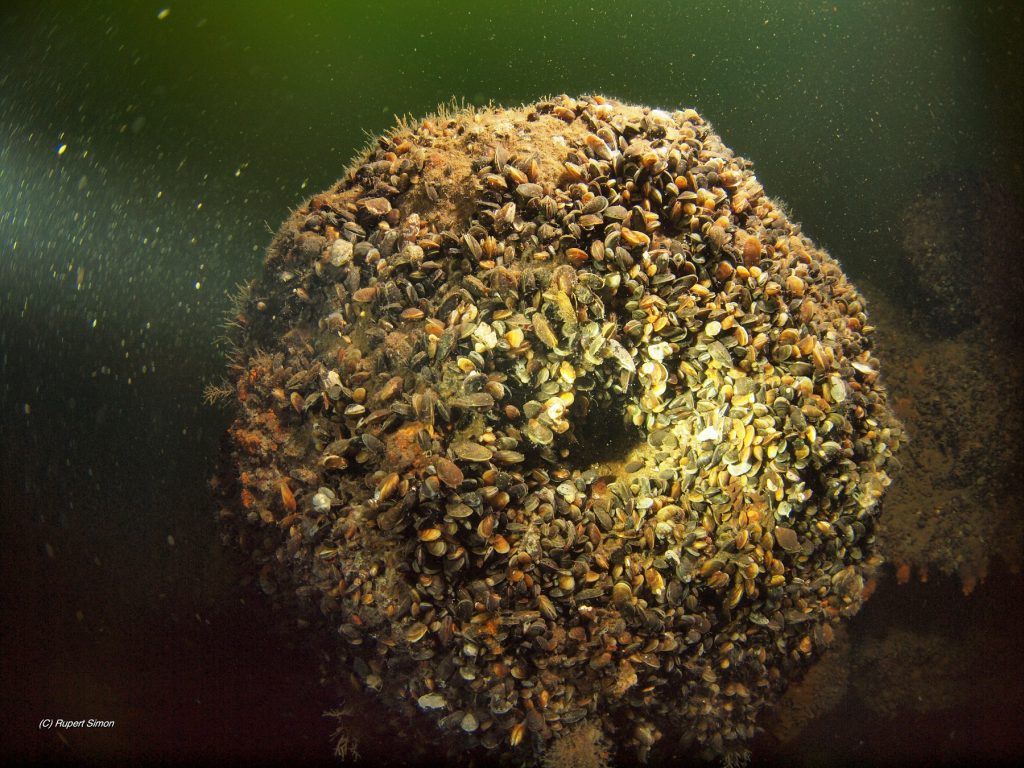

Other stakeholders include fellow wreck divers. For the diver, diving on wrecks is not necessarily connected to history. It can be driven by interest in aesthetic impression, fun, adventure, or the marine life that has taken up residence in the artificial reef. Many wreck divers simply partake just to enjoy the underwater world. As such, the age of the site is irrelevant.

I personally like to dive a site in Finland called “Stor Träskön tykkijolla.” The site contains a large piece from the side of a Russian two-deck line ship. Divers of our club—Nousu—reportedly saw two cannon barrels on the site. Despite many searches and to my great disappointment, I found only one. We all know that time changes everything, but consciously removing items from the seabed interferes with the experiences of other sport divers . Although I was informed that the missing gun barrel has been found, it lost its original historical value as it has been removed from its context without documentation. Why not leave things in place so we all can benefit from them?

UNESCO Underwater Heritage Convention

In its 31st session on the second November of 2001, the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation acknowledged “the importance of underwater cultural heritage as an integral part of the cultural heritage of humanity and a particularly important element in the history of peoples, nations, and their relations with each other concerning their common heritage.” They signed a document known as The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. The scope of the Convention protects all artefacts submerged underwater for 100 years or more. The Annex of the Convention contains ethical and scientific guidelines for activities within underwater cultural heritage sites. A detailed manual accompanies these documents.

Besides that, the sunken objects “may have a private or public owner, may be a marine peril—for navigation or for the environment—or deserve to be protected or managed for other reasons, for example as artificial reefs which became ecosystems, or marine gravesites transformed into venerated places,” Prof. Mariano J. Aznar of Spain writes in a special edition of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). ICOMOS is a non-governmental international organisation dedicated to the conservation of the world’s monuments and sites.

It follows that the introduced time limit of 100 years or older as criterion for protection is arbitrary. History is happening as we speak: Thus, a recently sunken item or ship can contain cultural heritage value. For example, remains of World War II mark history and should be considered and protected as heritage, too. Prominent examples for underwater heritage sites are Tirpitz in Lofoten, Norway; the HMS Royal Oak in Scapa Flow, Scotland; the MS Wilhelm Gustloff, MS Goya and SS Steuben in the Baltic Sea, Poland. All names represent tragic events and losses of human lives. Collecting items from wrecks is not just bad practice but illegal

The Finnish Example

In Finland, the Finnish Antiquities Act implementing the UNESCO Cultural World Heritage Convention protects ships or other artifacts that have sunk 100 years ago or more. The Finnish Heritage Agency and the Finnish Coast Guard work together to enforce the law. The authorities prevailed in a case involving the cargo vessel Vrouw Maria carrying goods ordered by Katharine the Great, Empress of Russia. In other cases, lawsuits are ongoing.

The Spanish Example

Spain’s interest in protecting the remains of its medieval and early modern fleet vessels has significantly increased during the last few decades. Spain has pursued—and won— several litigation cases in national and international courts. These cases indicate that underwater objects are rarely abandoned, but rather lost and still legally owned. Removing items from such sites cannot be considered salvage but theft. The main uncertainties around remains of Spanish warships may be in cases where the vessel sank in waters no longer under Spain’s jurisdiction. When Colombia became independent, it inherited the Spanish belongings in its territory. Does this apply to the San José, nicknamed the Holy Grail of Shipwrecks, which sank in now-Colombian waters? Is the wreck and treasure of the San José the property of Spain or Columbia? Does this really matter today? The ship sank more than 100 years ago and could as such be considered part of the world’s cultural heritage. It would be perhaps the best option that Spain and Colombia join forces and make the find available to the broad public using proper scientific approaches. The Convention suggests so.

The Example of the United Kingdom

David Cleasby, a British maritime archaeologist, told me a story of a modern anchor found by a diver near the historical wreck of the HMS Pomone, a 38-gun Frigate built in 1805 and lost in 1811 in Alum Bay, Isle of Wight. According to the Guidance from 2012—updated in 2018—by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency, part of the Marine Management Organisation, “If you intend to recover wreck material you may require a licence from the appropriate authority.” Lifting a heavy item with a crane close to an archaeological site disturbs the sediment, potentially affecting the nearby site. And, under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 it is “an offence to demolish, destroy, alter or repair…without scheduled monument consent…a maritime monument.”

It would be prudent first to apply for permission to assure that the site is correctly defined and not damaged. According to the Wreck and Salvage Law, every item retrieved must be reported to the “Receiver of Wreck.” This organisation deals with modern and historical “lost and found” items such as anchors, port holes, and coins. The legal practice assumes that every item has an owner and reporting enables the organisation to return the item to the owner and assess whether the item is historically important.

Hence, the Receiver investigates ownership of wreck items. When the item is returned to its legitimate owner, the finder is entitled to a reward. Unclaimed wreck items belong, after a year of waiting, to the Crown. The Receiver decides on behalf of the Crown whether the finder may keep the item or turn it over to the Royal authorities. So, in the UK, when you pick up an item and keep it without reporting your findings, you have stolen it from the Queen.

The Sustainable Future Of Wreck Diving

Is there a place for citizen science? In the preamble of the convention, the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization expresses its believe that (emphasis added) “cooperation among States, international organizations, scientific institutions, professional organizations, archaeologists, divers, other interested parties, and the public at large is essential for the protection of underwater cultural heritage.” Asking professionals to work together with amateurs and the public at large is simple citizen science. While this approach has century-old roots, it continues to gain traction in modern society. Can this approach be used for archaeology?

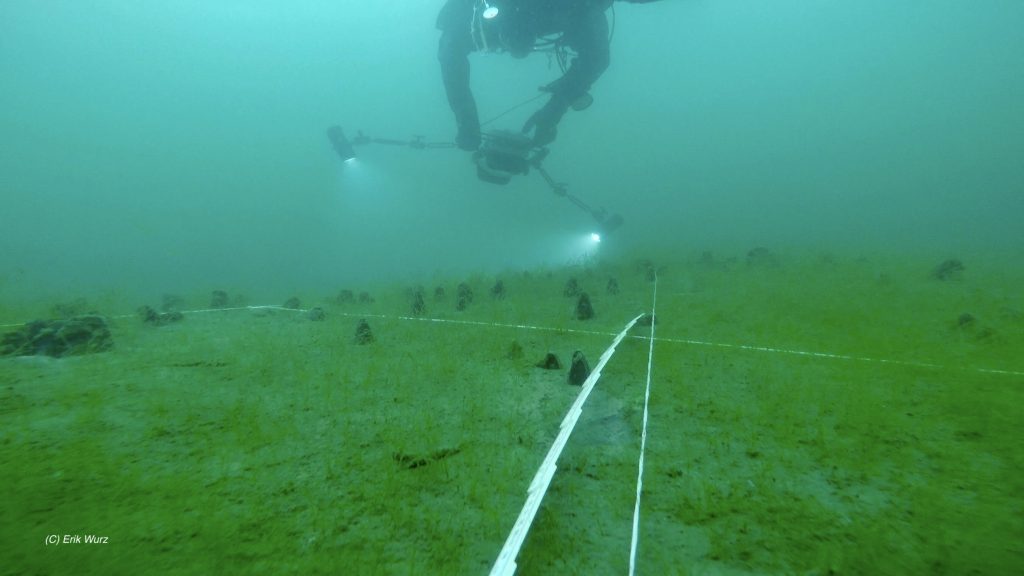

The Finnish Society for Marine Archaeology (Suomen Meriarkeologinen Seura or MAS) was founded in 1995 and promotes marine archaeological research, education, and hobby activities in Finland. MAS initiates and coordinates marine archaeological research, training, and seminars. For example, it has jointly organised the 7th International Congress of Maritime Archaeology (IKUWA7) to be held on June 6-10, 2022 in Helsinki with Helsinki University and the Finnish Heritage Agency. One of its flagships is the initiative Porkkala Wreck Park featuring dozens of 16th to 19th century historic wreck sites. The objectives are documentation, identification, and preservation of the underwater cultural heritage. Dive clubs are invited to “adopt a wreck” for monitoring of the status and maintenance of anchored mooring buoys. This collaboration of professional and amateur organisations can very well be seen as an example project where citizens are involved in science under the guidance of professionals and experts in the field.

The Baltic Sea Heritage Rescue Project

The German Baltic Sea Nature & Heritage Protection Association documents the condition of wrecks found in the sea, accounts for existing human remains, and notes the dangers to which the wrecks are potentially exposed. These threats are usually associated with illegal trawling, which can destroy wreck sites. Hence, removing ghost nets is the first step to approaching a new site. The work is carried out by volunteers.

Project Baseline

This initiative of the Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) intends to mobilise divers to engage as citizens and record changes in the world’s underwater environments. The website hosts dozens of local projects. Any diver can engage with scientific, conservation, and government entities to advance the restoration and protection of natural and cultural treasures. Although it mainly concerns marine biology and ecology projects, it may serve as an example of wreck monitoring and data communication with interested parties.

Badewanne

In the Gulf of Finland, nicknamed “Badewanne“ by the German Navy during WWII, a group of volunteer divers finds, documents, and identifies lost, forgotten, and found wrecks. The group uses scientific methods such as measuring the dimensions of the wrecked ship, photographing, videoing, and modelling using photogrammetry for documentation. The group collaborates closely with archaeologists and the Finnish Heritage Agency and produced the documentary, “Nazi Sunken Sub/U-745 Verschollen.”

Heritage Malta

The Maltese Government recognised the impact of diving tourism on its underwater cultural heritage items. It tasked its agency Heritage Malta to form a unit dedicated to Underwater Cultural Heritage. The organisation identified several sites that “may be accessed by divers in a controlled and managed manner.” It finds further that “the creation of new sites that can be visited by divers and through virtual reality will give added value to the diving tourism package.” With this protective management approach, Malta hopes to attract even more deep-water wreck diving tourism in the future and become a “market leader.”

Conclusion

By photographing and sharing the deep throughout the last century, ocean explorers Jacques Cousteau and Hans Hass provoked the development of diving tourism. The number of divers has grown exponentially since the 1970s, and experts estimate that seven million people actively practice scuba diving. [Ed.note—for a detailed study see: What is the size of the scuba diving industry?] About 2,000 divers visit the wreck of the cargo ship Thistlegorm, discovered by Cousteau in the early 1950s, each month. These estimates indicate the pressure that divers place upon cultural heritage resources, and the need for resource management. More importantly, we can make a difference by adopting the three golden rules:

“Take only photos, leave only (at most) bubbles, touch only your own equipment.”

Collaborations in projects mentioned above such as the EU wreck park, adopt a wreck, or Baseline, can increase the meaningfulness of our hobby to help us get more out of our dives. Keep diving safe, but keep it sustainable for your diving environments. If you are ready, look at the references of the previous section and engage!

Rupert Simon started his diving career in Belgium in 2003 under CMAS guidance and now teaches under the same flag. He completed technical diving training under CMAS, NAUI, TDI, and GUE standards. He chairs the Scientific Committee of the Finnish Divers Federation and coordinates their dive training. He is also a member of the Finnish Maritime Archaeological Society (MAS), contributes to preservation and marine archaeological work and manages the EU wreck park in Porkkala, Kirkkonummi, Finland. As a scientific diver, he’s focused on moving towards a sustainable future.