Exploration

SS RIGEL: THE CRYSTAL WRECK

Our young Italian explorer, Andrea Murdoch Alpini traveled to the Åland Islands, in the heart of the Baltic Sea to explore the remains of the Finnish cargo ship SS Rigel, which sank more than 100 years ago after being trapped in pack ice. Alpini offers up a Baltic elegy to the shipwreck’s icy remains. Here is his report.

Text and photos by Andrea Murdock Alpini. Translation from Italian by Cristian Pellegrini

I left Dalarö, Sweden, two days ago. I am now on my way to Mariehamn, the capital of the Åland Islands, in the heart of the Baltic Sea.

On the short two-hour drive from south of Stockholm to Kapellskär, where I embarked, I came across two elk, at least seven or eight deer, a beautiful red fox and several hares that approached right by my Wreck Van. When I arrived at Åland Islands, I wandered around all afternoon until late evening. Calm waters, swamps and coniferous forests that plunge into the sea make up the landscape of these picturesque lands.

It is said that love can be toxic. Sometimes the excessive presence of one partner can suffocate the other half of the couple. Every ship is bound to the surrounding sea, and the SS Rigel will forever be bound to the Baltic. The deadly embrace of the ice forced her to sink. Her hull will lie on the Swedish seabed, at least as long as the cold continues to preserve her and the winter currents aren’t too strong. Diving the wreck here by the 60º parallel was one of the most beautiful and meaningful experiences I have ever had.

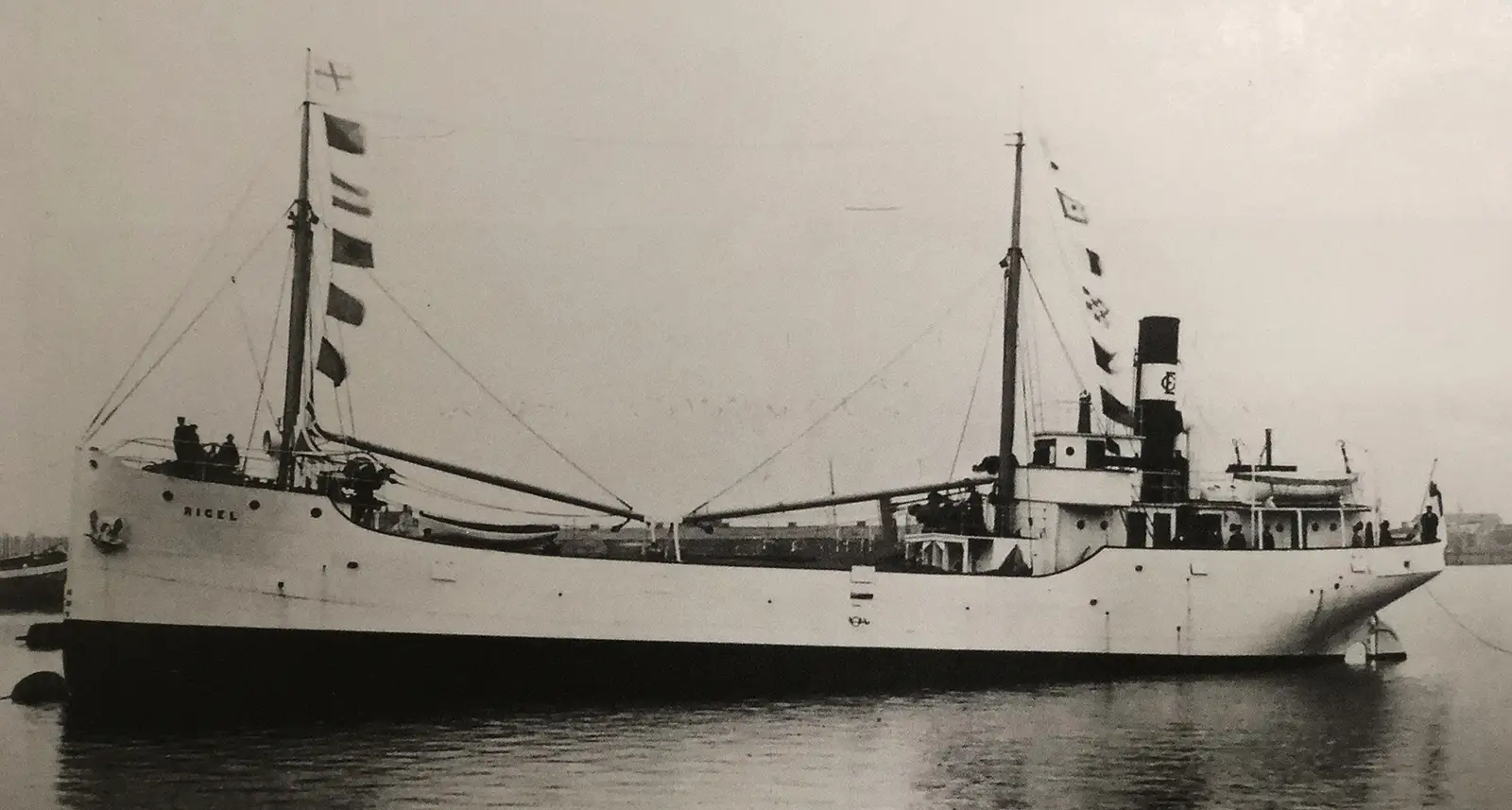

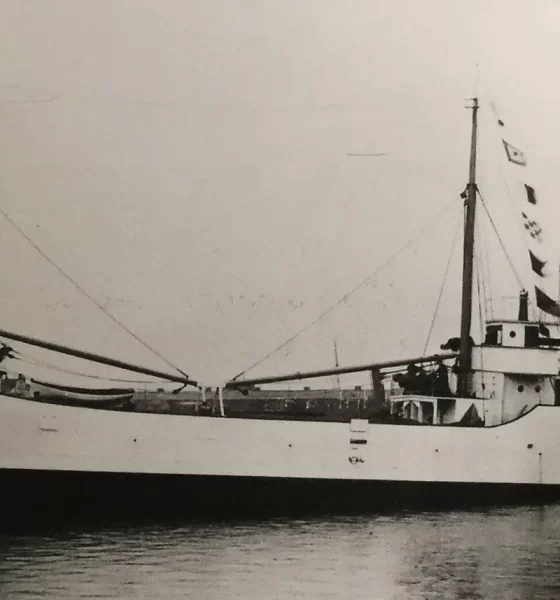

The SS Rigel wreck is located about thirty miles from Mariehamn. The ship was built in 1920 at the Finnish shipyards in Helsingfors, near Helsinki, for the Åland tycoon Gustav Erikson, owner of the largest fleet at the time. The ship was launched the same year by the Sandvikens Skeppsdocka och Mekaniska Verkstad shipyards, but her life afloat was short-lived. She would sink just three years after her launch.

The year 1923 will be remembered for the first 24-Hours Le Mans Grand Prix, but also for the first Time magazine cover. The magazine’s cover would feature many iconic world events, including the sinking of the beautiful liner Andrea Doria, three decades later (1956) off Nantucket. The crew of the Murtaja icebreaker will remember the winter of 1923 as one of the coldest ever. The ice was thick and solid.

Weeks and months passed, but the grip of the frost did not loosen. The SS Rigel remained captive for some time, then on 7 March 1923 the ice finally tightened its embrace around the ship’s hull, which succumbed to its oppressive, elemental force and transformed her from ship to wreck.

The final descent to the sea bed must not have been sudden, as today the SS Rigel lies in perfect navigation trim on the bottom of the Baltic Sea. Having set sail from the Swedish capital bound for Turku (Finland), after being loaded with general cargo, she was destined to never reach her destination port. The crew abandoned ship before the deck was completely crushed by frost. Everyone was rescued by the Swedish icebreaker Murtaja, which brought the crew back to Stockholm.

In Search of the Rigel

Our navigation aboard the Silverplein, Ville Lundqvist’s beautiful diving boat, proceeds at a speed of eight knots. We are about two miles East/North-East of Tjärvens Fyr, the exact place where the SS Rigel sank. The time has come to switch on the depth sounder and probe the seabed. After a few rounds of inspection, the color scale finally changes, and the frequencies on the monitor indicate the presence of a wreck. We launched the shot line with abundant line.

As I descend and look at the line in front of me, I feel the water particularly cold: 2º Celsius (35°F). It’s not just my feeling. Actually, currents from the North are bringing even colder water into the Baltic Sea. I planned to reach a depth of around 55 m/180 ft to come across the wreck. I am already at over 50 meters, and here the ghostly darkness that engulfs everything still does not even let me glimpse the dark black mass of the wreck… I am about two meters from the bottom, and still no trace of the ship.

My task of securing the line to the wreck is designed to make the descent easier for the divers who will come after me, and it is beginning to get interesting. Small stones made spherical by age-old currents are rolling along the seabed from the force of the current. Then, with my left hand holding the line, my eyes scan and find nothing until suddenly a gloomy mass towers above me: it’s the Rigel!

From below, the scene looks sinister. The current is strong, but I am still protected by the hull, and I am curious as to what challenges will be waiting for me on the other side. I secure the line to the wreck at the bridge, switch the lights on, and position them toward the wreck. I begin exploration knowing that the rest of the divers will arrive soon.

Initially, I am overcome by the current. The ship is only 44 m/144 ft long and almost 8 m/26 ft wide, and has a draught of 3.5 m/11 ft. Here, in the middle of the Baltic Sea, darkness envelops everything like cosmic nothingness. I find myself in a dimension that is both tactile and ethereal at the same time. The ship is in perfect condition, everything onboard is as it was the day it sank.

Up Close and Personal

The bridge stands on the first deck above. I approach it cautiously, as I don’t want to lose reference with my line. Today, unfortunately, the strobe light is not working correctly, even though during the pre-dive check on the surface, it appeared to be functioning correctly.

Meanwhile, on the Rigel, the command area is impressive. The wheelhouse is imposing with its compass and binnacle. The boat’s wheel is as big as the full span of two arms of a man of yesteryear. It would have taken big hands but, above all, strong fingers to hold the tiller of the SS Rigel. A wooden case that retains its shape and suggests a cozy, domestic space is still in place. Much of its wood is surrendering to the force of the sea, while a few planks resist. I extend my camera arms to give light to this space that lives in the abyss.

In stark contrast to the surroundings, the wood looks warm, the grain can still be appreciated, and here and there shreds of iron color the planks (?) with rust. The stern is nearby. Casting the light to my right I see it, with its winches and bollards. Obviously, I am drawn to it, but first I want to finish exploring the command area and the deck below. As I move to starboard, I am exposed again to the cold current, which initially makes me fin in vain, before I better understand how to tame it. The visibility is stunning, despite the pitch-black around me.

Arriving at the starboard, I am struck by the telegraph machine: it is perfect, beautiful, an icon of the early 20th Century. A few feet away is the mouthpiece, a tube whose end has the negative shape of the human mouth. By clasping its bite between one’s lips, the tube would carry the voice to the ship’s engine room, where the outstretched alert ears of the engineer officer would receive the commands given from above. The overview of these elements would be worth the dive, yet the best is yet to come..

I am alone on the wreck and have almost forgotten about space and time. This worn-out ship seems immortal. Only the sound of my breathing, which I feel deep in my chest and which makes my ribcage vibrate, brings my attention back to real life. Down here I am certain I have found my Baltic Elegy. A wreck with a bare history has gifted me with the deepest and most vital breath that these icy waters hold.

The deck is almost unrecognizable, the ship’s vitality here seems to disappear, highlighting the marks that glaciation has left on it. Like a jellyfish tentacle on living flesh, the ice has left its eternal scratch on the dead metal sheets of the once vital SS Rigel.

Baltic Elegy

I fin until I reach the foredeck, then I feel an inner unease. Although I would like to see the sea-cutter, I feel I have strayed too far from the heart of the wreck. Both my stage cylinders and the wide-open camera arms have made it more difficult for me to overcome the currents, which has tended to push me back. I return to the stanchion on the ship’s side and head towards the quarterdeck.

A navigation light with thick concave and convex glasses appears from out of the darkness. Shortly after that comes another one, then another. Could it be that I have reached the lights room? It has always been my dream to find a place full of lanterns on board a ship.

A smashed door lies hunched over itself. The brass handle and lock are still tightly screwed to their wood. A glare of light reflected from one of my lights shifts my attention towards the interior, and there it is, the bosun’s room!

On the shelves, all lanterns are in place. Placid, mute, they have stopped spreading safety with their own brilliant light. I count one, two, three, four, five lanterns. I think it would be perfect to name this room the Hall of Mirrors, as if we were in Versailles.

Who turned off the sun? The walls seem to disappear, and I indulge in a midsummer dream. And so, in the long frosty night enveloping this crystal wreck, blades of light appear, tearing through the darkness. Diving the SS Rigel wreck represented for me a true inner experience, staged on this relatively small ship. There I found what I really was looking for from the Baltic Sea. A shrill seagull echoes in the distance. I climb aboard the Silverplein, and shortly afterwards a mustached seal appears through the waves.

DIVE DEEPER

Wrecksite.eu: Rigel SS (1920~1920)

YouTube: WRECK DIVING – SS RIGEL – ÅLAND by Dennis Olsen

Facebook: S/S Rigel by Baltic Underwater Explorers (BUE)

Other stories by the prolific Andrea Alpini Murdock:

InDEPTH: The Aftermath Of Love: Don Shirley and Dave Shaw

InDEPTH: Finessing the Grande Dame of the Abyss

InDEPTH: I See A Darkness: A Descent Into Germany’s Felicitas Mine

InDEPTH: Stefano Carletti: The Man Who Immortalized The Wreck of the Andrea Doria

InDEPTH:My Love Affair with the MV Viminale, the Italian Titanic

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and PSAI technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor based in Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming, and writing. He holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. Andrea is also the founder of PHY Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching open circuit scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophy of wreck and cave diving. He published his first book, Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti (2018) and his next, IMMERSIONI SELVAGGE, was published in the fall of 2022. Recently he published a new wreck-historical book: ANDREA DORIA: UN LEMBO DI PATRIA (2023).