Conservation

Restoring Coral Reefs In Bonaire

InDepth editor Amanda White ventures into the depths of coral restoration with Reef Renewals Foundation Bonaire (RRFB)’s Francesca Virdis. To date, the organization has replanted 25,000 corals and is now planning to scale up restoration efforts.

By Amanda White

Header photo by David J. Fishman of outplanted Staghorn corals.

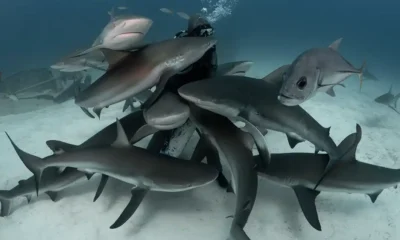

Coral colonies serve as the foundation of coral reef ecosystems, and their rapid decline could mean a loss of habitat for more than 25% of marine life that depends on them to survive. With coral bleaching and rising ocean temperatures becoming a headlining concern across the globe, what can be done to help save this critical ecosystem? Hope is not lost. We caught up with environmental scientist Francesca Virdis, the coordinator for Reef Renewal Foundation Bonaire, a non-profit organization that is growing and replanting corals around the island of Bonaire, to find out how they are working to save the reefs.

InDepth: What is Reef Renewal Foundation Bonaire (RRFB) doing to address the loss of coral reef habitat?

Francesca Virdis: We started in 2012. The first phase of the project was to collect coral samples from the reef from different strains, or genotypes, of two different coral species—staghorn and elkhorn corals. Once the most abundant coral species in the Caribbean region, their populations have now been reduced by over 90% and are currently listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List and in the Endangered Species Act. This is the most important reason why we chose to work on the restoration of the population of these two species. Furthermore, they are branching and fast-growing corals, so they are easy to propagate and can show visible results in a short time.

After the initial collection, we brought these 200 coral samples to the nursery, and from there on we started propagating thousands of corals every year.

What is the project’s ultimate goal?

The ultimate goal is to assist in the recovery of degraded coral reef areas using active coral restoration as a strategy to preserve and enhance the population of coral species.

It’s not just about placing more corals on the reefs to increase coral abundance but also about working in terms of diversity—adding different strains of coral colonies to the wild stocks. When we outplant corals back to the reef, we want to strategically promote genetic diversity. In fact, different coral strains have different strengths and different abilities. For example, some of them could better withstand diseases, be more heat tolerant, or grow faster.

Environmental conditions are changing, and they will change even more in the near future, so to give the reef a chance and increase its resilience, it’s critical to work on biodiversity.

How do these nurseries work?

Since 2012, RRFB has grown corals using a “tree” nursery design. It’s called that because the structure resembles an antenna or a Christmas tree. The nursery trees are made of PVC and fiberglass, anchored to the seafloor at a depth of 5-8 m/15-25 ft.

Each tree hosts between 100-160 corals of the same genotype. These are propagated from the same donor colonies that were collected originally in 2012 to populate the nursery. Corals hang on the trees and are suspended in mid-water. New fragments are cut from the growing colonies, using a technique known as “coral gardening,” creating new generations of corals. These corals are re-suspended back in the nursery, and the process begins again. Corals remain in the nurseries until they reach the proper size, and then RRFB selects them from the nurseries and outplants them onto the reef.

How many corals have you planted since 2012?

From the same parent colonies, we can produce thousands of corals every year. We have more than 110 trees underwater that hold a total of 13,000 corals that you can count at any given time in our nurseries. To date, we have outplanted back to the reef more than 25,000 corals.

When do you replant the corals outside of the nurseries?

Corals remain in the nurseries until they are reef-ready, meaning the overall health and size will give them a higher chance at survival when exposed to predators and other stressors outside of a nursery environment. Once ready, corals are selected from the nurseries to be outplanted onto restoration sites, which are degraded reef areas where these species of corals were in the past or are still present but in low density.

As a baseline, we use maps that show how the corals were distributed in Bonaire more than 30 years ago.

How does the replanting process work?

Based on the area size and bottom type, we choose the number of corals, strains, and outplanting techniques. RRFB uses different outplanting methods depending upon the substrate.

For hard rocky bottoms, we use marine epoxy to attach the corals directly to the substrate. When no hard substrate is available, we use elevated biodegradable bamboo structures that are built-in sand/rubble areas to provide a substrate to attach corals. Corals, which are tied to the structures using cable ties, eventually cover the entire structure and grow down toward the substrate.

How long does it take from the beginning of growing them to when they are replanted? What’s the timeline?

It depends on the coral species and the initial size of the fragments. On average it will take about 6 to 8 months max to get outplanted to the reef.

How do you manage to plant all of these?

With the help of many volunteer divers, tourists, residents, and local dive professionals who work for the four dive shops that are members of the Foundation and support this project. The Foundation at the moment has only two employees, therefore the dive shop support and the community involvement are extremely important for us.

How do you monitor the corals that you have replanted?

Before we plant, we do a photomosaic of the reef area we want to restore. Photogrammetry allows us to compare how the site looked before and after our work. Then, using image analysis, we can pull out different metrics to evaluate the performance of different strains that have been planted. We do in-water surveys as well to monitor survival and evaluate potential stressors such as diseases, predation, etc. We come back to the restoration sites and monitor their development on a yearly basis.

What are the major threats facing the coral reefs in Bonaire?

I would say one of the major threats is water quality. We do have a sewer system, but only the buildings in town and within 100 m/328 ft from shore are connected to it. The rest of the buildings have very old septic tanks, which often leak. Untreated water means more nutrients flowing to the ocean, which leads not only to more algae growing on the reef but also the presence of more bacteria and viruses, which potentially can lead to more diseases. Furthermore, in town, there is an increased number of moored boats, which are not required to have their wastewater treated. Because Bonaire is located outside of the hurricane belt, many boats visit us for several months a year and their wastewater gets discharged straight to the ocean.

Another factor that is affecting the water quality is sedimentation. Bonaire is a dry island with free-roaming goats eating the vegetation; this negatively affects the retainment of sediment. When it rains, a large amount of sediment gets washed away into the sea, contaminating the water and suffocating the corals. In addition, we are witnessing unsustainable coastal development. Often, because of the lack of regulation and enforcement, we have buildings too close to the ocean or artificial beaches with imported sand. If not properly handled, the majority of the sand gets blown into the ocean during or right after the construction process.

Are the corals you are replanting more likely to survive the water quality?

Reducing stressors is definitely paramount for the success of the project. The Bonaire National Marine Park, together with the government and stakeholders, is working toward improving water quality on the island, educating tourists, and protecting the reefs. We have been successful in the majority of our restoration sites. However, having a long-term water quality monitoring program could help us to better understand why corals are affected more in some areas than in others. Our outplanted corals are also used as bio-indicators of environmental conditions. A lower survival rate after outplanting can help draw attention and actions to preserve degraded reef areas.

Do you think it’s possible to restore coral reefs on a large scale?

Although it’s crucial to protect what we have by reducing the stressors that are affecting the reefs, restoring coral populations is a tool to buy time, and it’s faster than what people imagine. It depends on the coral species, but some of them are fast-growing, and we have been able to repopulate several sites, some as large as 3000 m2 /32292 ft2in just a couple of years, by outplanting no more than 2500 corals. In Bonaire, we are currently working on a “midscale” but we are looking forward to improving our efficiency and expanding in the future.

Bonaire Reef Renewal partners with Project Baseline, how does that fit with your mission?

The idea behind the Project Baseline partnership is to promote coral reef awareness and to show people that a positive change is possible. Sadly, most of the Project Baseline projects are currently showing negative trends, which reflects the reality of nature preservation around the world. Through our project, we want to give a message of hope and show people that something can actually be done. Often when witnessing nature degradation, we feel powerless and don’t know what to do. With our work, we want to empower people and show what each of us can do to make a change.

What are your future plans?

We want to scale-up the restoration effort in Bonaire and support other locations to help them to develop successful restoration projects.

We recently started working on three additional boulder coral species—star corals in this case. We have been working on a new nursery design that is able to host these species of corals because they grow in a completely different way than the branching corals we currently work with. We recently obtained the permit to set up the nursery and, within the next two years, we are planning to produce at least 6,000 corals per year of these massive corals.

We have also recently established a new partnership that allows us to bring an innovative restoration technique, known as larval propagation, to Bonaire. This technique is based on collecting reproductive material during coral spawning, fertilizing the eggs on land, and outplanting recently settled larvae back to the reef. The larval propagation technique uses the corals’ sexual reproduction as restoration method, and, more importantly, gives us the ability to dramatically scale up the number of coral outplants, work with numerous coral species and morphologies, and increase the genetic diversity of corals on reefs.

How can people get involved?

The dive shops that are supporting the foundation are responsible for the training of our volunteers, who are tourists or resident divers. Sometimes people are not interested in volunteering, but they still want to learn about it and support the project, so part of the class fee goes to the foundation as a donation. With the help from our supporting dive shops, so far we have trained more than 1,000 people as coral restoration divers.

Non-divers can also show their support by donating. One of the options is to purchase material from our online wish list and bring it with them when they visit Bonaire. Most of the material is affordable, but it is expensive for us to have it shipped. We invite everybody planning to visit Bonaire to check the wish list on our website.

Dive Deeper:

Diving In Bonaire by Manuel Bustelo

Nourishing My Inner Tekkie at Bonaire Tek by Michael Menduno

Amanda White is an editor for InDepth. Her main passion in life is protecting the environment. Whether that means working to minimize her own footprint or working on a broader scale to protect wildlife, the oceans, and other bodies of water. She received her GUE Recreational Level 1 certificate in November 2016 and is ecstatic to begin her scuba diving journey. Amanda was a volunteer for Project Baseline for over a year as the communications lead during Baseline Explorer missions. Now she manages communication between Project Baseline and the public and works as the content and marketing manager for GUE. Amanda holds a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism, with an emphasis in Strategic Communications from the University of Nevada, Reno.