Conservation

Preserving Florida’s Springs: The Bottled Spring Water Problem

There’s no doubt that Florida’s Springs are imperiled. Most are flowing 30% to 50% less now than their historical average and are suffering from eutrophication. However, as veteran hydrologist Dr. Todd Kincaid explains, the problem is not spring water bottlers like Nestlé, in fact they could be allies in the fight to preserve the springs.

By Dr. Todd Kincaid

Header photo by Florida DEP of Wakulla Springs in April 2008.

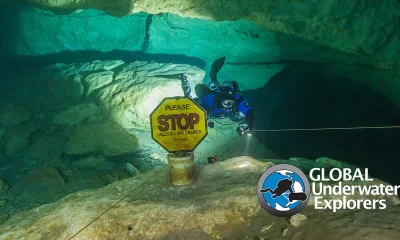

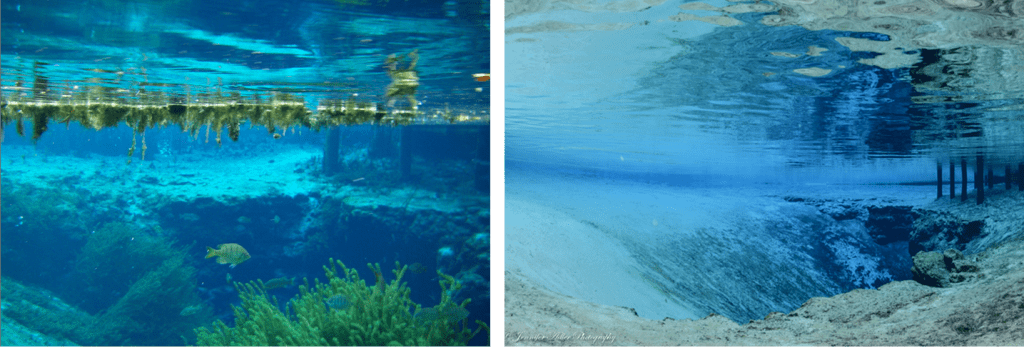

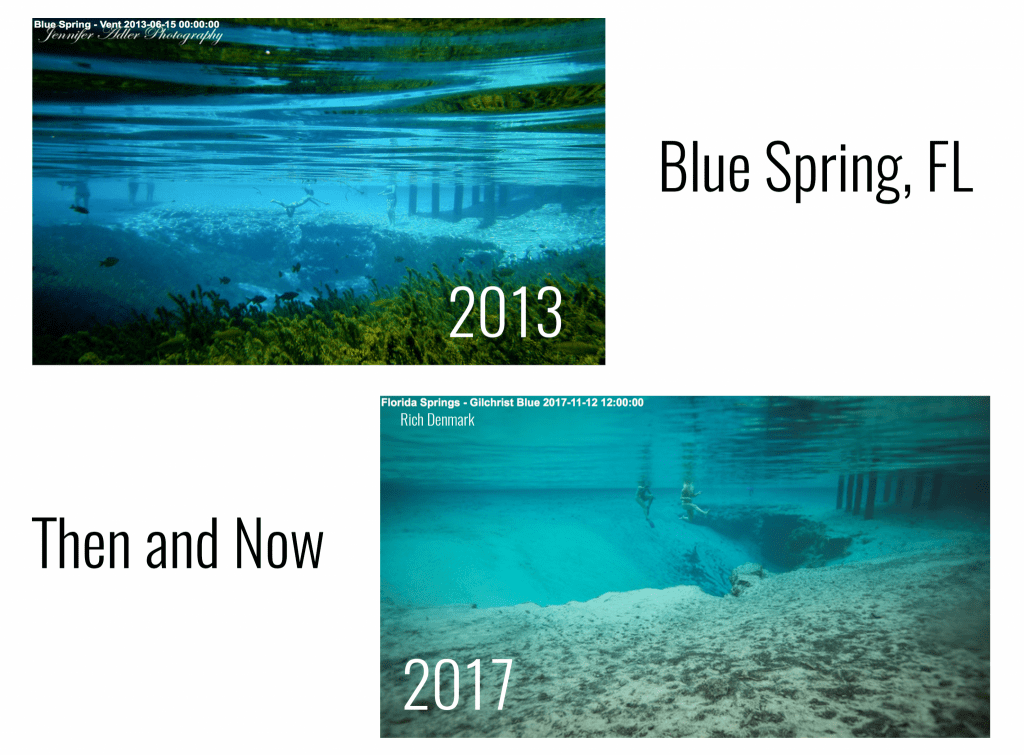

Florida’s Springs are imperiled. Most are flowing 30% to 50% less now than their historical average. Some don’t flow at all except after big storms or abnormally wet periods. Nearly all have become overwhelmed with algae and bacteria (eutrophied) due to excessive nutrient pollution. The causes are straightforward and increasingly hard to ignore: groundwater over pumping, the overuse of fertilizers by agribusiness and homeowners, and insufficiently treated wastewater. Solutions exist, can be widely implemented, and would significantly improve spring water flows and spring water quality, but they require major investments and diversions from status quo: caps on groundwater extractions, tiered fees for groundwater usage applied to all users, tiered taxation on fertilizer usage, advanced wastewater treatment, transition away from septic systems, etc.

Existing policies have failed to even bend the steep downward trajectory of Florida’s springs. “Minimum Flows and Levels” (MFLs) appear to protect spring flows but, in reality, they open the door to continued declines while people argue over the difference between natural and human causes. “Best Management Practices” (BMPs) pretend to reduce nutrient loading, yet are not only unproven and unenforceable, but not even conceptually capable of the needed nutrient reductions. Even as more and more attention and resources are directed at the condition of Florida’s springs, most continue to degrade: less and less flow, more and more nitrate and algae.

In the face of these declines, it’s easy to become disheartened and jaded. It’s even easier to become focused on reactionary measures aimed at what we don’t want and be rooted more in emotion than in facts. This is, I believe, epitomized by the highly publicized reactions to a permit renewal application filed with the Suwannee River Water Management District (SRWMD) by the Seven Springs Water Company for a bottled spring water plant down the road from Ginnie Springs.

The application requests that the SRWMD renew a standing permit that was first issued in the 1980s for the extraction of 5 million gallons per day (MGD) of groundwater from the Floridan aquifer to support spring water bottling. This same permit was voluntarily reduced to 1.1 MGD by the property owners to prevent the possibility that it could be incorporated into one of the many groundwater pipeline schemes that are persistently proposed to transport water from relatively rural north Florida to the substantially more populous cities in central and south Florida. Through the years, several different companies have leased the property and had access to the water, one of which was the Coca-Cola Company, and the most recent being Nestlé.

My perspective on this issue is a product of 30 years of work on karst hydrogeology in Florida, more specifically from my work for Coca-Cola on mapping groundwater flow paths. Specifically, we mapped the pathways to the springs on the western Santa Fe River, including Ginnie Springs, and identified the threats to the quality and quantity of flow to the springs. Even more, my perspective reflects the evolution of my understanding of what it’s going to take to sustainably manage groundwater (synonymous with spring flow) in Florida.

The problems facing Florida’s springs are not technical and not a consequence of any one particular use or user. The real problems are instead failures of the established policies to take the necessary steps to put concrete limits on groundwater consumption and pollution. If we are to achieve sustainable spring flows, limits on groundwater consumption must be established and enforced and, in reality, must be lower than current levels.

From a quantity perspective, who gets the water is irrelevant. All that matters is how much is taken. At present, not only is too much being taken, but there are no established limits. Conservation measures enacted by one user simply opens the door for new or larger allocations to other users. This is accomplished when users of the water claim a “beneficial use”. So, while we can and should be proud of those engaged in conservation, the reality is that spring flows will continue to decline.

If we are to restore and preserve spring water quality, nutrient pollution, specifically the input of nitrate and phosphorous into Florida’s groundwater that stimulate the explosive algae growth in Florida’s springs, rivers, lakes, and estuaries that nobody wants, must be dramatically reduced from current levels. Some experts state that nutrient discharge levels will need to be cut across the board by 70% or more in order to meet water quality targets for Florida’s natural waters. That would mean 70% less nutrient loading from agriculture, 70% less nutrient loading from households, and 70% less nutrient loading from wastewater treatment and disposal.

At present, and for the foreseeable future, there is insufficient political will to achieve any of these needed changes given resistance from corporate and special interests. Year after year, proposed legislation calling for the types of sweeping changes needed fails to receive sufficient public support for passage. While the political efforts that would result in real and positive change continue to fail due to lack of support, the public’s attention focuses on perceived impacts from individual users without regard to the actual impacts those users and uses have on the springs.

Bottled spring water is only one example. Though the entire industry uses only around 1/100th of 1% of the groundwater extracted from the Floridan aquifer and produces absolutely none of the toxic nutrient loading that is killing the springs, it holds a disproportionate grip on the public’s attention to usage, impacts, and solutions. If tomorrow the entire bottled water industry in Florida were to shut down, there would be effectively zero improvement at the springs in terms of either flows or quality. The little amount of water gained would very likely be quickly and quietly allocated to other users.

If, on the other hand, the roughly 400 bottles of water needed to produce a single bottle of milk were put to better use, say returned to the springs, and the associated nutrient loading to groundwater due the fertilizers used to grow the feed, were thereby eliminated, there would be a near immediate improvement in both flow and quality of water at the springs. Milk production uses far more water and produces drastically more nutrient pollution than the production of water. The water saved by eliminating milk production would, therefore, take longer to re-allocate to new users and eliminate a huge portion of the nutrient pollution that is killing the springs as well.

Far more water is used for that purpose, and much more nutrient pollution is caused.

Eliminating the production of milk, for example, would also require more time to re-allocate to new users and would eliminate a substantial portion of the nutrient pollution that is killing the springs.

Nearly every drop of water extracted from the Floridan aquifer and not returned reduces spring flows by an equal amount. Certainly from the entirety of the state north of Orlando and Tampa, and regardless of what it’s used for, from water from household taps, watering lawns and golf courses, car washes, crop irrigation, production of milk, soda, energy drinks, and bottled water. Similarly, all the nutrient loading to groundwater west of central Orlando and Gainesville and south of Tallahassee flows to the springs and contributes to the explosive algae infestations, which no one wants to see become normal.

The problems plaguing Florida’s springs stem from these realities, regardless of whether the springs are enshrined as State Parks or privately owned. Florida’s springs need allies not rhetoric—allies who help to build the public support necessary to achieve the only actions that will restore and preserve spring flows and spring water quality: caps on groundwater consumption and dramatic reductions in nutrient loading.

Regardless of corporate culture, spring water bottlers’ economic self-interest is directly aligned with springs protection. Spring water cannot be treated and cannot be captured if there are no more springs. Spring water bottlers, therefore, rely on access to sustainable, high-quality spring water. It then follows that they, along with other like-minded entities, can be strong allies for springs protection. It’s time for Floridians to stop focusing on rhetoric that fails to yield even as little as a diminished rate of springs degradation. It’s time to start working toward real solutions anchored in the realities of water and nutrient budgets. The bottled water industry is not sucking Florida dry, but denial and political inaction are.

As an organization focused on sustaining the environmental quality and required to support healthy underwater ecosystems, our task must be to confront environmental problems from a perspective grounded in the realities of what will be needed to achieve our goal. We must work for what we know we want rather than against what we think we don’t want. And to be successful, we’re going to need as many allies as we can muster.

At Project Baseline, we should and will seek to engage with the people and organizations who share our goals, even if doing so is not palatable to some of our fellow conservationists. We should work with those entities and use our voices, our votes, and our wallets to foster the policies and the actions that are needed to restore and preserve the type of underwater world we want to dive in, be awed by, and pass along to the next generation of underwater explorers.

Dive Deeper:

Project Baseline is a nonprofit organization that leverages their unique capacity to see how rapidly the underwater world is changing to advance restoration and protection efforts in the local environments we explore and love. Since 2009, Project Baseline has been systematically documenting changes in the underwater world to facilitate scientific studies and establish protection for these critical underwater environments.

Learn more about Project Baseline

View their online database

Get involved

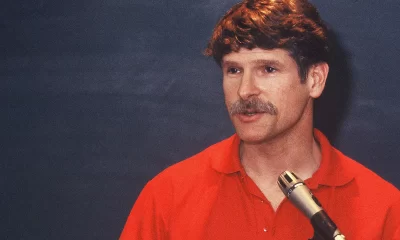

Todd is a groundwater scientist, underwater explorer, and advocate for science-based conservation of water resources and aquatic environments. He holds BS, MS, and Ph.D. degrees in geology and hydrogeology, and is the founder of GeoHydros, a consulting firm specializing in the development of computer models that simulate groundwater flow through complex hydrogeologic environments. He has been an avid scuba diver since 1980, having explored, mapped, and documented caves, reefs, and wrecks across much of the world. Todd was instrumental in the founding of Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) in 1999 and served on its Board of Directors and as its Associate Director from its inception to 2018. Within the scientific and diving communities, Todd advanced the use of volunteer technical divers and the data they can collect in endeavors aimed at understanding, restoring, and protecting underwater environments and water resources. He started Project Baseline with GUE in 2009 and has been the organization’s Executive Director from its beginning. More on Todd at: LinkedIn and ResearchGate