Cave

Los Cinco Cenotes— Exploring Upstream Ox Bel Ha

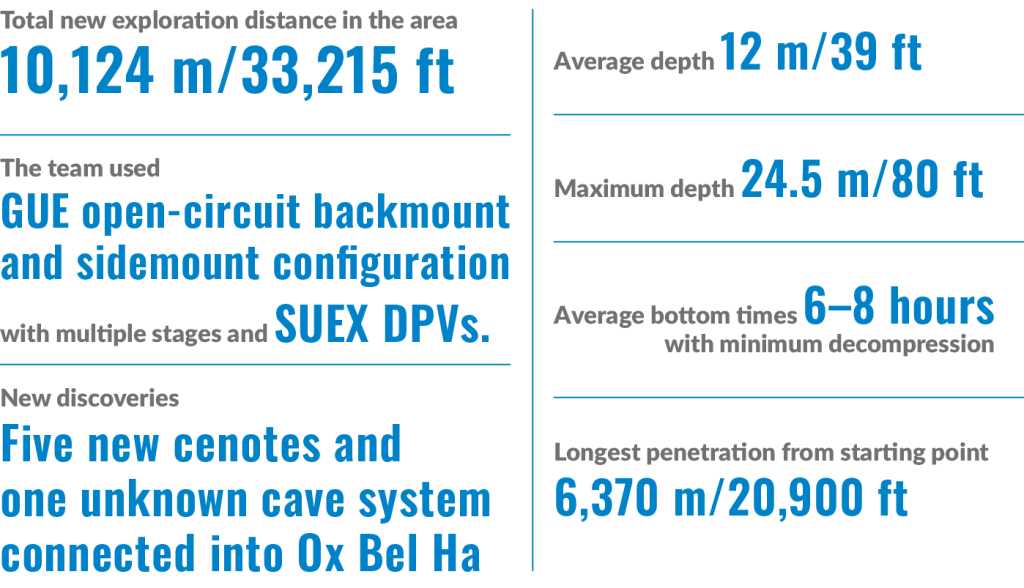

Emőke Wagner, Bjarne Knudsen, and László Cseh, continue on their chosen mission to explore, survey, and map as much of Riviera Maya’s underground waterways as humanly possible. Over the last year, the team has extended upstream Ox Bel Ha with 10.12 km/33,215 ft of new line and discovered five new cenotes. These were big dives! Bottom times averaged 6-8 hours, with avg. depths of 12 m/40 ft and a maximum penetration of 6.4 km/20.9k ft. Here is their report.

by Emőke Wagner, Bjarne Knudsen and László Cseh, aka Team BEL. Note that Bel also means “path” in Mayan. Images courtesy of BEL unless noted. Lead image: BEL diver, Emoke Wagner taking notes of possible future exploration lead. Photo by Tom St. George

Ox Bel Ha is one of the largest underwater cave systems in the world with many hundreds of kilometers of known passages and is located south of the town of Tulum in Quintana Roo, Mexico. The cave has been actively explored by cave divers for more than 25 years, but new discoveries are still made quite frequently, even today. A giant cave system like Ox Bel Ha often has a limited number of access points, and many corners of the cave can stay hidden even from trained eyes due to its complex tunnel characteristics. Tunnels exist both above and below the halocline level which further complicates exploration. The system is located in a coastal area and the underground tunnels exit in three different vents into the Caribbean Sea.

After a really diverse and successful exploration year, the BEL team moved on to other interesting areas of Ox Bel Ha late last summer. The objective was to resurvey existing lines upstream at slightly greater penetration distance than usual, northeast of the Gemini area. Our old survey data ended around 3.1 km/10,000 ft upstream from our starting cenote called Yax Chen. Additionally of course, we hoped to find undiscovered areas of the cave which could be pushed and explored.

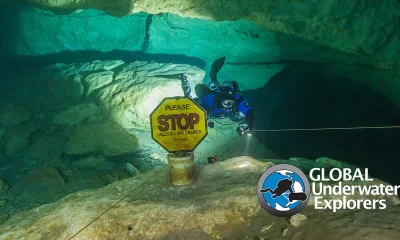

Since the majority of the tunnels were huge, the team has used mainly Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) open-circuit backmount configuration. The first smaller breakthrough for the team happened quite early in the project, during a survey about 3.6 km/11,800 ft upstream. A very defined but big tunnel was discovered which kept heading further north for another 300 m/90 ft straight. After this, unfortunately, the new tunnel bumped into old existing line, but at least it created a really convenient bypass for the team for future work toward the southwest. Shortly after additional recon and survey, the end of the old southwest tunnel seemed to end in front of a densely decorated row of columns. The team carefully navigated the space between the cave formations and, after two narrow turns, the cave seemingly opened up. There was not much flow present, and tannic water got stuck on the ceiling, but still the size of the cave gave hope for more exploration.

As more dives followed and we kept pushing forward, we laid 1,275 m/4,200 ft of new line there. The beginning of this section surprisingly consisted of white colored limestone walls, and the first 200 m/660 ft were very well defined. After this, the cave started to spread downstream in multiple directions. One side tunnel traveled for another 250 m/820 ft below the halocline, into the saltwater. Here the cave is very beautiful with lots of stalactites and stalagmites covering the ceiling and walls. Sadly, this part of the cave descended deeper; flow completely stopped and ended in tiny saltwater passages hitting 23.5 m/77 ft of depth.

The southeast off-branching of the new mainline there looked more promising as it stayed in the freshwater part of the system with slightly more flow. Smaller, siltier sections followed until the cave opened up again, but hit a massive collapse. There were signs on our survey from before that this might happen, but since there was an old line existing on the opposite side of the collapse, it gave us hope to push through openings between the rubbles. Unfortunately, this never happened, so we wrapped up remaining leads and returned to more re-survey of old lines to the northeast as the original plan suggested.

A Breakthrough

After a decent amount of survey dives, our major breakthrough in this project happened. The start of it, however, did not look so promising. Even if surveying through massive freshwater tunnels with flow, it is not a bad idea to keep smaller side possibilities in mind, often hidden under ledges, closer to the bottom of the main tunnels out to the side. Following this technique, about 4.8 km/15,700 ft upstream from our starting point, the cave seemed to open up to the east. “Open up” might be an overstatement, since the new corner was borderline backmount-sized, but the flow made it worthwhile to travel ahead. Finally, after 150 m/490 ft of new line, the cave really opened up, and we popped into a massive freshwater room with dark decorations and gray-colored sediment hills. Even though this immediately gave reason for celebration, it was nice to swim around more and really make sure that a huge tunnel like that contained no line. To our surprise it looked like we were the first ones there.

Every time a potentially good discovery like this happens, one side of the explorer is very excited about how much cave we potentially could find while pushing on while the other side realizes the distance and the difficulty of our new, smaller, tunnel to get there. We decided the best option would be to return and try to find a better route to the same big room, while traveling through the small section one more time and following the flow going through this huge room downstream. That should lead us toward old lines and, hopefully, from there the travel would be easier. At a penetration distance of nearly 5 km/16,400 ft we wanted to use the simplest and shortest path, especially if we needed to come back frequently to explore the new area. To our luck, on the next dive we managed to connect back very easily and quickly into an old line nearby, which greatly simplified things for us going forward.

The goal for the team after this was obvious, we were ready to push the newly discovered room further upstream to the northeast. This first dive went really well, the cave maintained its characteristics and was big and easy enough to follow the way of the water. We observed some leads on the sides, mainly to the east, but they were not a priority at that point. The main tunnel went for another 300 m/1,000 ft and,in some corners, had unexpectedly high flow levels for Mexican caves in this region. Then, strangely, where the cave looked the biggest, the flow just dropped, and all the edges of the decorated walls closed in.

To the east there was a quite big sediment hill with a narrower tunnel behind it and plenty of percolation from the ceiling. Since we had gas left, we decided to check the lead but, after two turns, there was a very silty major restriction ahead of us, but seemingly there was ongoing cave behind it. Out of curiosity, we pushed through and, except for the expected zero visibility, navigating the restriction went well. On the other side, we had time for a few more tie-offs with our reel and, by the time we had to call the dive, it really looked like the cave would continue. The flow was still present, and the cave became slightly bigger again.

Although we managed to pass by our initial small section, our next dive meant that we then had the above-mentioned restriction at a penetration distance of 5.1 km/16700 ft to deal with. Navigating it was manageable, but if the cave was going to go further on the other side, coming back with more equipment for future dives would make our dives much more difficult if there was no way around this. Logically, the next dives were spent checking other leads nearby; maybe at least one of them would go around our restriction, but sadly it was not the case. We had to prepare for this new challenge.

Long Distance Logistics

Assuming the cave would continue after the major restriction, we knew we needed to prepare for it accordingly. There are a multitude of variables to consider on dives like this, since the cave can be considered shallow (average depths ended up being around 12 m/39 ft), but there would be: long range travel (amount and type of scooters, batteries), long bottom times, CNS, more stage bottles, navigating the restrictions with more equipment, delays, failures, and fatigue. We will talk in more detail about these challenges in another article soon.

Figuring out all the logistics and trying to prepare as well as we could for the following dives, we attempted to push the cave past the restriction. Navigating the narrow part was very difficult, even though we left all the scooters behind. The cave stayed small and took a lot of hidden/awkward turns, often going through old collapses. The rock was very porous and soft and we had to be efficient with survey and line work to maximize visibility due to percolation from the ceiling. To our dismay, after 100 m/330 ft, we faced another major restriction. Luckily, this one was solid rock unlike the previous one, but it was even smaller in size. After this squeeze, the cave really opened up, it looked similar to the tunnel before the first restriction both in size and features.

We followed its defined nature for another 250 m/820 ft, and suddenly the tunnel arrived at another massive room. There was a bit of flow, but again the tannic water was also visible on the ceiling, so we realized this could be another swampy-like area hidden from the old mainline. We chose a direction (south) and pushed as long as we had line. The cave just stayed huge and traveled in and out from halocline while seemingly offering a lot of leads along the way. We tied our last line down after another 250 m/820 ft, penetrating to 5.7 km/ 18,700 ft from our starting point. Again, we left the dive very happy, but also slightly concerned about how to proceed. To our luck, on the long way home while navigating our silty restriction, it looked like there could be a slightly bigger corner available for us on the west wall.

All of us agreed that we would like to keep exploring, despite the challenge, and we should try again to make our challenging sections as comfortable as we could, since it looked like we could be busy in this area for quite some time. Identifying the west wall for the restriction seemed like a good starting point. We had to move the line. The problem was that with the conditions in the cave there, we only had seconds available to modify anything. Luckily, we succeeded, and this side of the restriction proved to be better for transporting more gear.

The next dives after this focused on the early leads on the other side of both restrictions, since we still hoped that there could be a separate tunnel existing nearby which avoided all these complications. On one of these dives, to our surprise, we bumped into an old line. Pushing the end led us to the discovery of the first new cenote we found in this section, named Cenote Ciego. Surveying the rest of the existing line revealed that unfortunately we could not use this path in the future as it did not connect into Ox Bel Ha anywhere else except on our line, which is past the restrictions. This little, unknown, system is now part of the Ox Bel Ha cave system thanks to our efforts. It seemed like we would really need to use the lines we had established before to explore the rest of the cave in the future.

Five Cenotes and 10.1 km of New Passageways

Initially, it sounds quite discouraging to travel regularly beyond 5.5 km/18,000 ft with two major restrictions at 5.1 k /16,700 ft, utilizing backmounted doubles, four stage cylinders, and two DPVs per diver, but the more we had to deal with all this, the easier it got. The first push dives went really well. The goal was to travel southeast first, and check where the water flows.

On the first dive, we discovered three additional cenotes, named: Turtleshell, Sunhole and Silty. It looked like all of them were circling around one major collapse, also visible from the satellite pictures. The furthest southeast corner of this part of the cave had organic sediment and contained the biggest collapse. For a while, we squeezed through between the rubble following the water, but at 5.9 km/19,300 ft, it looked like there would be no way onward. Later, pushing the cave to the northwest-northeast proved to be challenging in a different way: the cave kept going longer, but it looked like the only opportunity to continue would be if we committed to the saltwater section. The freshwater did not want to go toward the northeast, which is very strange since the flow initially in this section came from that direction. Not to mention historic sections of Ox Bel Ha (Esmeralda region) are relatively close, so we all thought there would be another connection there waiting for us. Realizing this wouldn’t happen, we focused our efforts on the deeper saltwater section.

Probably the last thing that could have made this project more difficult would have been to increase the depth of the dives. Greater depths could potentially require some decompression obligation from us; we knew there would be less gas available to explore, and caves in this region rarely continue from the deeper layers. Despite all this, there was not much else left for us to do there, other than to descend deeper and see what happened there.

Before our eyes, one of the nicest and biggest saltwater tunnels we had seen so far appeared. With the distance and depth (around 24 m/78 ft), we quickly realized swimming there with our reels would not make much sense. So we had to develop good and efficient techniques laying line on the trigger and the same for surveying. This allowed us to maximize exploration time, consume less gas, and look calmly around the cave. Luckily, the conditions were very good in this deep section, and the tunnels stayed big until the end. It really looked like northwest would be the best path to take and, surprisingly, after a 210-m/690-ft huge, well-defined, straight passage, the cave ended in another collapse.

It seemed like we needed to drop scooters and try to climb over the hill and check the two last possible leads. However, unfortunately, none of them continued. This dive was special also, because we managed to reach a penetration distance of 6,370 m/20,900 ft. This distance could likely be the longest underwater travel on an exploration dive in Mexico. After wrapping up some final leads in the area, this section totaled a network of 6,145 m/20,160 ft of new line.

Finally, this August (2023) we managed to focus our efforts on all the remaining leads to the northeast of the Gemini area, close to our initial start at 3.1 km/10,000 ft from last year. Since many of the leads were less promising and smaller, the team switched to GUE open-circuit sidemount configuration. Surprisingly, some leads on the east side of the cave opened up nicely, going through silty, tannic and collapsed areas.

Conditions were overall bad, but still the last month’s effort added a few more kilometers of new cave to the project, totaling 10.1 km/33,200 ft of new tunnels being discovered. On one of the last dives in the area, following an old lead led us to the discovery of one more cenote we named Cenote Luise. The cenote had crystal clear water and was big, but flowing water stopped there, and it looked like there was no way forward on the other side of the sinkhole.

We would like to thank our supporters for the help we received for this project: Halcyon Dive Systems and Dr. Mario Valotta for equipment, Cuzel filling station for bottles and standard gasses and Derek Zhi with Felix Rodriguez for pictures and video. BEL team cave divers: Emőke Wagner, Bjarne Knudsen and Laszlo Cseh.

Data

DIVE DEEPER

YouTube: Thrilling Cave Diving Adventure | Ox Bel Ha Mexico Vlog by Bjarne Knudsen, Emőke Wagner and László Cseh, aka Team BEL.

InDEPTH: In The Line of Duty: Surveying 12.7 km of New Cave Passage by Bjarne Knudsen, Emőke Wagner and László Cseh, aka Team BEL.

InDEPTH: Laying Line in Ox Bel Ha by Bjarne Knudsen, Emőke Wagner and László Cseh, aka Team BEL.

The BEL exploration team was formed in 2019 and their main focus is to further extend the the Ox Bel Ha cave system, one of the largest cave system in Mexico. The name BEL represent the team members first initials, and “Bel” in Mayan translates to “path.”

Emőke Wagner is originally from Hungary and began diving at a young age. She has been an active instructor since 2014. After a couple of years spent traveling around the globe, she moved to Mexico in 2017. While living in Mexico, cave diving became her real passion, and she began exploring more of the local cave systems. Since 2016, Emőke has been working as a full-time GUE instructor instructor and is currently teaching the cave, foundational, and recreational curriculum. She is the youngest female instructor and youngest explorer in GUE.

László Cseh is from Hungary and has always been fascinated with the underwater world. He became a recreational diving instructor in 2012 and began teaching and traveling. After becoming a GUE instructor in 2016, he moved to Mexico to look for new diving challenges. Local cave exploration possibilities helped him achieve his GUE Cave instructor certification. Laszlo is teaching Cave 1 and Cave 2, as well as the GUE Cave Sidemount level.

Bjarne Knudsen began diving in 1993, taking his first tech classes in 1997 and his first GUE Cave and Tech classes in 1999, so has been part of the GUE community since the early days. In the early 2000s, he spent some years in Florida, where he was a part of the WKPP. During this time, he also pushed Sheck Exley’s end of line in the Cathedral Cave system with Todd Leonard (and lots of support from friends). Bjarne is currently on a slow world cruise with his wife on their sailboat. For the last few years, they’ve been a little stuck in Mexico and the surrounding countries, which offer so much nice diving.