Latest Features

Learning from the Deep with Nuno Gomes

Explorer and author Andrea Murdock Alpini sits down with deep diving pioneer and cave explorer Nuno Gomes to discuss his approach to deep diving and what he has learned in the process.

by Andrea Murdock Alpini. Images courtesy of Nuno Gomes and the author.

If you love deep diving, you likely know some of its most legendary names—the “Lords of the Deep.” Their names will be forever engraved on the greatest milestones of deep diving.

Even with a buddy, there’s solitude in the deep. It’s similar to taking a walk alone—you can get lost in the depths of your mind. Walking alone is an important practice—one that I do before planning a deep dive or an exploration. On these solitary walks, I often reach the ultimate depths of my feelings.

The stars are brightest on the darkest nights; the draw of the unknown is strongest on the deepest dives. Even if you have logs full of experience diving wrecks and caves, everything changes when you find yourself in the deep—remarkably alone in the water, far from the surface, where the eyes of the cowries watchfully await your return.

Touching the bottom is a privilege reserved for a few. Amongst them, a name shines: Nuno Gomes.

I had the chance to meet him—a living Lord of the Deep. Last year, I was invited to speak at Boston Sea Rovers. I remember the moment I heard him call my name: “Hey, Andrea!” from down a corridor of the venue. I was surprised he recognized me in the middle of a crowd. We spent three days together, talking and exploring each other’s mind-worlds. Our chat ended with an open question: “How deep is deep?”

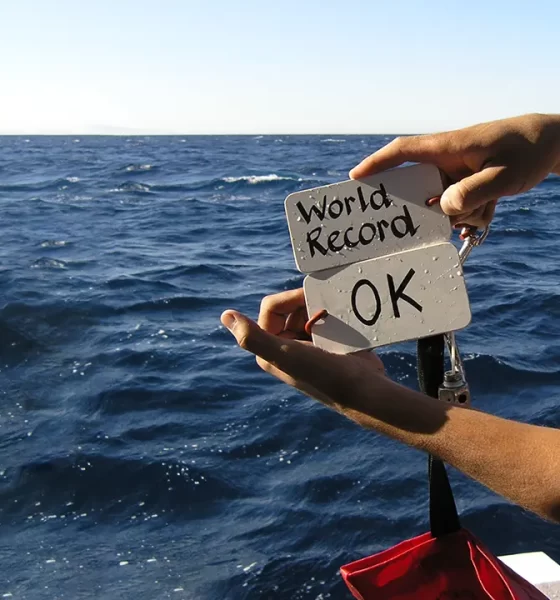

Nuno Gomes is a diving instructor with the Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques (CMAS). He is also a Professional Civil Engineer and a Commercial Diver. He is best known for his two world records in deep diving (independently verified and approved by Guinness World Records). He achieved his first depth record in 1996 at the Boesmansgat cave in South Africa at a depth of 283 m/927 ft.

Because the cave is located at an altitude of approximately 1,550 m/5,086 ft above sea level, the decompression schedule was equivalent to a sea-level dive to 339 m/1,112 ft. The total dive time was 12 hours and 15 minutes. He achieved yet another record in 2005 in Egypt, in the town of Dahab, in the Red Sea. The recorded depth—318.25 m/1,044 ft—excluded the rope stretch. The actual depth was somewhere between 321.81 and 323.28 m/1,056 and 1,061 ft. The total dive time was 12 hours and 20 minutes.

If you wish to dive into this story from the comfort of the shallows, grab a hot cup of coffee and settle in. If you want a taste of the intoxication of the deep, shake up a few martinis (and keep them coming). Please don’t hold your breath while reading.

Andrea: What was the dive that changed the way you saw scuba diving, Nuno?

Nuno: My first “open water” dive was done in a cave to a depth of 55 m/180 ft—it was great. I knew that diving was perfect for me.

“Deep” is a word with different meanings. What is “deep” to you?

Theoretically, any dive below 30 m/100 ft is deep. The maximum depth offered during training is 100 m/328 ft ( using trimix); below that, you are diving at your own peril. Below 240 m/800 ft, we enter the world of “Ultra Deep” diving. Only a few divers dive that deep. Once one goes below that depth, the diver impairment increases quite a bit—both physical and mental activities become more difficult.

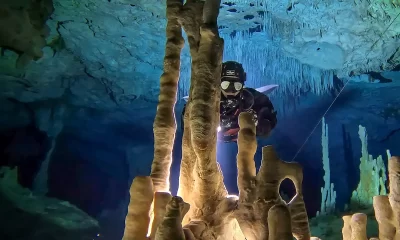

What is the essence of solo cave diving?

Solo diving is diving alone in a cave or in any other environment. There is a saying: “Dive alone, die alone.” Solo diving is not recommended but, when doing “Ultra Deep” dives, it [solo diving] is probably safer due to your inability to save your buddy at that great depth.

Who is (or was) the greatest cave diver of all time, in your opinion?

I think Sheck Exley was the best cave diver ever. He did some monster dives, all on open circuit—and many of his dives were world records.

Would you say that he was your scuba diving role model?

The late Sheck Exley was definitely my role model.

Sheck was not a big talker; he was a doer. He was a clever, unassuming man who got along with his fellow team divers. Obviously, his physiology was exceptional because he had a high resistance to nitrogen narcosis and oxygen toxicity. His adaptation to HPNS was possibly lower than expected; this may have been what led to his demise.

Have you ever exchanged information and feelings with other deep divers?

No, not really. I did however learn quite a bit from diving with Sheck Exley.

Sheck’s dive plans were simple, but he dove his plan. On one dive, I was his sole deep diving support diver at 90 m/300 ft, on air. Other support divers assisted from 60 m/200 ft and shallower.

Speaking of planning, can you describe how you plan a deep dive?

Speaking of planning, can you describe how you plan a deep dive?

First, I analyze the conditions at the site and how they vary from day to day. I determine, “What is the target?” and try to figure out what is needed to do the dive in terms of equipment, gases, team, and safety measures.

I also have to pick a suitable time of the year to do the dive—the time with the best conditions. I do build-up dives at the site before executing the dive.

Afterward, I analyze the problems I encountered and come up with possible solutions for future dives.

Describe your feelings at the bottom of a deep scuba dive.

It depends very much on the gases used, the depth, and the site conditions.

I have done many deep air dives to 100 m/330 ft; it is difficult to perform at that depth, especially if there is any work involved. Using trimix makes it a lot easier, but—obviously—the dive plan can be more complex, and the decompression would be longer. Below 240 m/800 ft, I have experienced additional diver impairment—a “narcotic effect”—no matter the gas blend, even with a small percentage of nitrogen.

Describe your feelings at the bottom of a deep scuba dive.

It depends very much on the gases used, the depth, and the site conditions.

I have done many deep air dives to 100 m/330 ft; it is difficult to perform at that depth, especially if there is any work involved. Using trimix makes it a lot easier, but—obviously—the dive plan can be more complex, and the decompression would be longer. Below 240 m/800 ft, I have experienced additional diver impairment—a “narcotic effect”—no matter the gas blend, even with a small percentage of nitrogen.

What is your worst nightmare underwater? What about your best-ever moment underwater?

What is your worst nightmare underwater? What about your best-ever moment underwater?

My worst nightmare is to have more problems than I can deal with and solve—this means that you could die. Since I am still alive, this has not yet happened, but I have been close. One example was when my main regulator stopped working at a depth of 271 m/890 ft.

Probably my best moment underwater was when I first saw and touched a coelacanth fish, at a depth of 115 – 120 m/377 – 393 ft, off the coast of South Africa.

How do you imagine the future of deep diving with rebreathers?

A lot of divers are using rebreathers and doing some very deep dives. It is easier to plan a dive with a rebreather and the logistics are far less [extensive]. It makes it almost too easy, but there are more potential failure points. If nothing goes wrong, it is great—but it is often very difficult to even know that you have a problem. Gas density is always a problem—especially when diving “Ultra Deep.”

As one goes deeper, the gas becomes denser, and it becomes more difficult to vent the lungs. Not being able to vent your lungs properly increases the percentage of CO2. There is a direct relationship between gas density and “narcosis” or overall diver impairment.

There is no question that deep diving is hazardous. Lots of divers die trying to dive deep. A lot of divers are becoming blasé about what deep diving is—mainly because it has become easier to go deep, especially when using rebreathers. In commercial diving, dives below 50 m/165 ft are handled completely differently, and the safety measures increase dramatically: such as the need to have a decompression chamber on site. They know what they are doing—they’ve experienced fatalities.

Looking back to the past, what have your mistakes taught you?

I have been lucky to have survived all of my mistakes. I have learned that all diving equipment fails. It is essential to have redundancy for all the equipment, including buoyancy compensators. When I was stuck in the mud at the bottom of Boesmansgat, one full wing could not lift me out of the mud: Inflating the second wing is what saved me.

What was it like diving Boesmansgat?

I have done hundreds of dives in that cave. One needs to respect that cave: It is big and very deep. I have always enjoyed diving there, but the cave is waiting for you to make a mistake. Not many people dive there, but three divers have died there—one of them was Dave Shaw.

What is the limit for you? How deep is too deep?

What is the limit for you? How deep is too deep?

Depth limits are variable: It all depends on the environmental conditions on the day as well as my physical and mental condition on that particular day.

When did you start thinking about setting a record in scuba diving?

I never thought about records—I just kept on diving a bit deeper and, one day, I had a record.

Were there any medical professionals involved in your world records process? Did they help plan the dives or comment on your approach?

No medical researchers were directly involved in my world records—except, in the determination of my condition after dives, DAN was invaluable. I have been part of some research projects in conjunction with DAN regarding micro bubbles following deep dives. I’m also involved in a preliminary study for the determination of the toxicity of oxygen, nitrogen and helium.

Would you attempt more records in the future?

Anything is possible—I am in good shape. But I don’t have anything concrete in the back of my mind right now.

How has your knowledge of oxygen narcosis changed how you plan your dives?

All gases are narcotic to a greater or lesser extent. In the case of oxygen, there is not much that you can do about it—it is necessary for survival. Some deep divers use very high partial pressures of oxygen. Hannes Keller used a partial pressure of oxygen of 2.48 for his 300 m/984 ft dive—successfully. Not many divers can cope with that. Extended times exposed to oxygen during decompression are also a problem; again, some divers can cope better than others.

Do you consider nitrogen to pose the greatest risk, or have you encountered any other bad gases you meet along your path?

All gases have problems—probably, carbon dioxide is the king of bad gases. It is approximately 13 times more narcotic than nitrogen. Another light gas that divers are looking at to replace helium is hydrogen. The only problem is that it is explosive when exposed to percentages of oxygen above 4%.

What kind of scuba books did you read to learn what you know about this discipline?

There are quite a few scientific papers available. Also, I read many books, including the US Navy Diving Manual and Professor Albert Bühlmann’s books on decompression, which were invaluable. I was fortunate enough to personally meet him. We met at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, and we talked about using or not using nitrogen in deep diving. He did not see any reason for using any nitrogen. We also talked about how saturation and desaturation rates are inversely proportional to the square root of the atomic mass. This property relates to how quickly the effects of a specific gas will be felt by the diver. Helium will saturate and desaturate 2.65 times faster than nitrogen: √28/√4=2.65

What can a tech diver learn from your experience?

Experience is very important, but one can also learn a lot by reading about the experiences of others—mostly from books. It is important to try and learn from other divers’ mistakes: It is safer than learning from your own mistakes.

The best way is to learn from past mistakes that you have survived—but it’s even better to learn from the mistakes of others.

Twenty years ago, I was an architecture student at University in Milan, Italy. I remember the day I read my first American book about theories of modern architecture. It was an epiphany for me. The book was Learning from Las Vegas by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour.

Venturi was a brilliant architect who studied with Louis I. Kahn—one of the biggest names in contemporary architecture. The young Robert Venturi used to say, “I stumbled into Coca-Cola cans, and my master Khan was stumbling into Egyptians’ antiquity.”

What does this mean? Everyone seems to stumble into their own milestones.

Reading old and dusty scuba diving books is a way to find your own path, but how can we design a new era of scuba diving? This is the question.

We have just one option: learning from the deep—and our past mistakes. There is no future without memory.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Diving Beyond 250 Meters: The Deepest Cave Dives Today Compared to the Nineties by Michael Menduno and Nuno Gomes

InDEPTH: Karen van den Oever Continues to Push the Depth at Bushmansgat: Her New Record—246m by Nuno Gomes

Other stories by the prolific Andrea Alpini Murdock:

InDEPTH: Deep In Italy’s Grecanica Wreck Valley

InDEPTH: The Aftermath Of Love: Don Shirley and Dave Shaw

InDEPTH: Finessing the Grande Dame of the Abyss

InDEPTH: I See A Darkness: A Descent Into Germany’s Felicitas Mine

InDEPTH: Stefano Carletti: The Man Who Immortalized The Wreck of the Andrea Doria

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and PSAI technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor-trainer based in Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming, and writing. He was awarded the Golden Trident as scuba explorer and researcher in June 2024.

Andrea holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. He is also the founder of PHY Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophies of wreck and cave diving.

He has published several books: Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti (2018) and IMMERSIONI SELVAGGE (2022). Recently, he published a new wreck-historical book: ANDREA DORIA: UN LEMBO DI PATRIA (2023). And, in early 2025, he released NOMADE DEL PROFONDO, with stories of cave/mine diving, wrecks, and interviews with three American “ oaks” of contemporary scuba diving.

He runs explorations on deep south wrecks of Italy on board his Raffio.