Cave

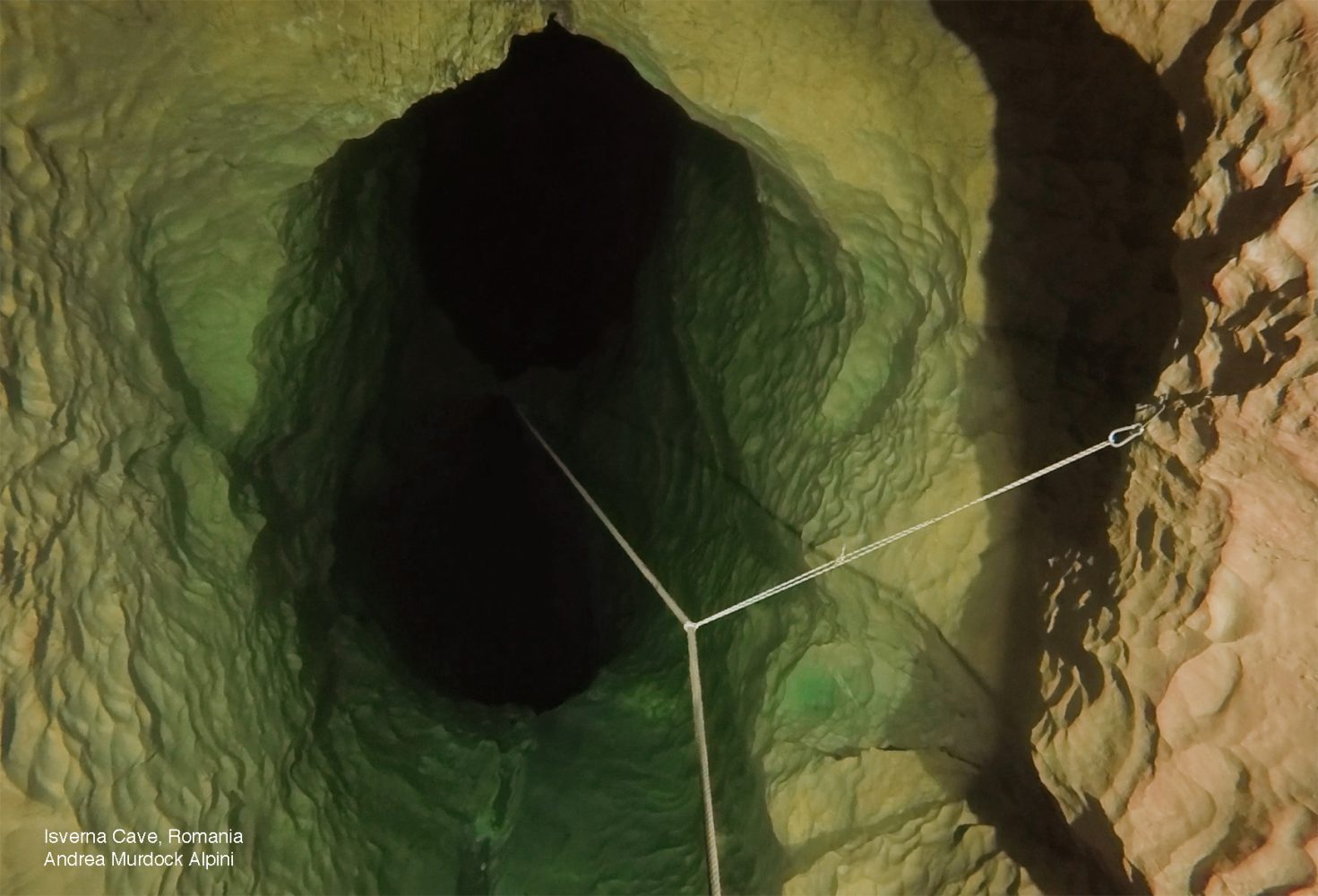

Isverna Cave, Diving An Underground Dacia

Italian explorer and tech instructor, Andrea Murdock Alpini, waxes poetic about his first exploration dive in Isverna Cave, located deep in the Earth beneath the wilds of Romania.

by Andrea Murdock Alpini

Film and Photos by Andrea Murdock Alpini

Early in January 2020, feeling fortunate to dive the stunning Isverna Cave located in the Balkans, Andrea Murdock recorded his impressions in a diary as it is shown here.

ISVERNA CAVE, The Trip

Footprints, steps and transfers

A small team of divers, Stefano Beatrizzotti, Nathan Zot, and Luca Bricalli from Switzerland, and I, the fourth diver and also the writer and filmmaker, are ready. We’re going to dive into this stunning cave with three siphons: Green Syphon, a narrow passage with a strong current; a breath-taking dry passage to the Yellow Syphon; and finally the Black Syphon, which is more than 400 m/1312 ft long and 42 m/140 ft deep—the longest flooded siphon in Romania. The permissions have been granted, and we have a goal to accomplish: an amazing adventure among these ancient rocks.

Isverna Cave is located at around 600 m/1959 ft elevation, in the Oltenia region, bordered on the north by Transylvania, made famous by the legend of Count Dracula. The first recorded exploration took place at the beginning of WWI, in 1914, and it has been studied and thoroughly written about over the years by many intrepid pioneer speleologists, with each century contributing additional vital information. Even Jacques Yves Cousteau brought his contribution to the exploration of Isverna Cave in 1990. In 2005, the scuba speleologists Gabor Mogyorosy and Mihai Baciu found a way to the end of Black Siphon. Reaching the back gate of Black Siphon means we will have explored more than 1800 m/6000 ft of cave. However, never fear, there are hundreds of virgin tunnels that await intrepid adventurers.

Isverna Cave: Day I

We arrived in Isverna around noon local time. We had driven more than 1650 km/1000 mi in one day to reach our destination–the wilderness in Romania. In spite of our late arrival, a very calm guy welcomed us. He spoke only Romanian. Very few words, along with hand signals were used to show us to the rural “house” where we were to sleep and remain dry during our stay. Our humble abode had but a single light bulb to illuminate it, and the ‘heat’ was a fire that we took turns attending to before we jumped back into our sleeping bags for warmth.

Isverna Cave: Day II

Early in the morning, while the others still slept, I had walked to the river. I approached the cave by the external side, a semi-vertical wall of 3m/10 ft close to its entrance. A crystal-clear tiny river flowed below the main rock wall. Mosses and lichens covered the whole surface of the rock and made it very slippery. On top of it was a locked iron gateway that guarded the access. The local authority had given the key to our speleologist: Mihail Besesek.

When we were all gathered, we saw a rope at the right of the entrance to the cave. I carried my heavy bag on my back with some of my diving gear. I let go of my mass on the heels of my boots, but “not enough” Luca Bricalli said. He is an expert alpinist, and his recommendations are very useful. I lifted up the front light worn on my helmet to light up the narrow passages of the dry part of the cave. We had to walk about 220 m/720 ft before we reached the inner lake. It was incredible how the concept of slippery, narrow, safe, and precarious changed with each step. The more we moved forward, the more the morphology of the cave changed. Now and then we had to proceed on our hands and knees, skipping flooded spots around 1 m/3 ft deep. A rapid river flowing along our journey reminded us as to how difficult the dive would be.

The march moved on quite simply according to our enthusiasm but the more I walked, the more I slowed down. Sometimes I got lost in the beauty of the cave’s rooftop: indented and smooth simultaneously. Phreatic rocks made me feel wrapped in the Earth.

The airy and aquatic human feeling that we usually experience living on the surface of the Earth disappeared. Only hardness, and the fickle ruggedness of the underground remained. The rock with its achromatism seduces the person who looks at it with simple eyes.

Thirty minutes into our journey, we came to a section of the river that needed to be forded, causing us to lose time. Mostly, however, we struggled with the climb, as handholds and footholds were not easy to see.

Charon

When we were 200 m/656 ft from the entrance, we came to a lake that required us to use our small rubber boat to cross. I couldn’t avoid thinking about the Italian poet, Dante Alighieri, who wrote of an angel helmsman to whom souls sing as they are being sailed to Purgatory.

We moved the bags, cylinders, twinsets, camera, lights, drysuits and much more scuba gear to the opposite side of the lake. The operation took more than twenty minutes. A smooth, slippery, sliding rock, 30 m/100 ft, was our base camp inside Isverna Cave.

The lake was transparent, calm, and flat, as opposed to the rowdy river. On top of the slide we saw the entrance of the beloved Green Siphon for the first time.

In the cave, our voices quieted down, and the power of silence rose up. Each of us had a light on our heads in order to see where we were putting our hands. I had brought all my video gear and deco stages to the beginning of the siphon. For me, to stand up with the steel twinset 15+15 filled to 260 bar/2800psi, was extremely difficult. In fact, I needed to roll over onto my side and use my knees to stand up. I knew the rule: don’t bring it if it’s not necessary, and I broke it. My back didn’t appreciate my flagrant disregard for rules, but my soul did.

Base Camp

Everyone had defined his square meter as a living area. “Wearing the Inside-out” by Pink Floyd could have been a perfect song for the moment. I had prepared all my gear except for the camera and lights, which were mounted and were heavy and bulky for the large branches. I had needed more time to get ready to dive.

On this day I dived the three siphons with video equipment, which was a challenge. Sometimes I was in great pain; the flow was strong, and finning, breathing, and filming were tough. The worst moments were at the end of each siphon, when gravity forced me to feel all the weight. I was able to capture stunning dry passages in between the flooded parts, amazing views, powerful colors, and exquisite concretions.

At the end of the first day of diving in Isverna I knew I could not have given up the video equipment. I remember a moment, at the end of the first siphon, I was gripping my camera with my right hand and holding a floating rope with my left hand to help to get out of the flow. Once I was out, a narrow tunnel had to be navigated. On the left wall there was a black/brown rock with a skinny rope to hold, and on the other side, and under my feet there was a river with a strong current. I moved forward slowly with my video camera and the heavy weight of my twin set on my back muscles aching and breathing with difficulty, but blissfully happy.

The beauty of rock

The first siphon runs for more than a hundred meters. It descends quite rapidly to 15 m/50 ft deep, where a fault cracks the bottom, a nice spot for filming. While I was finning, I used my free hand, the one not gripping the camera, to dust the floor of the cave. A layer of sand covered the spare parts of some enchanting chromatism by the rocks. This simple operation meant waiting before the silt settled and the powerful saturated colors of the stones were bright again.

The dive profile of this segment of siphon is a yo-yo: fast descent, flat bottom, and then sudden ascent to follow the form of Isverna Cave’s tunnel. By the way, this first part of the dive had gone faster than we expected. I decided I wanted to come back the next day to pay better attention to the surrounding areas that were on the main line.

When I was back at the surface, I was touched by the color of the rocks I saw in front of me. The dome is apparently wide. A small colony of protected bats live here. They are not the heirs of Dracula, of course, but their presence here gives a magical feeling of being there. I barely shined my lights, and the bats beat their wings and flew away, back into the darkness. While I watched the bats, the surface flow pushed me in the wrong direction.

I was finning strongly enough to keep my trim and keep filming. My wrists felt pain on the grip, the lights had been too large and heavy, so I had taped a lot of floating foam on the video camera equipment to lighten it and make it neutral underwater. Then and now I feel like I had a sail in front of me that slowed down my finning. It seemed that the wind slowed me down and made me lose momentum.

Walking the dry tunnel while wearing the full equipment required strong fortitude and determination. Sometimes the water rose suddenly from my ankles to my shoulders. When it covered my mouth, I breathed with my regulator and hopped on my toes. “You must be a dancer,” I repeated in my mind for those long moments, but I felt clumsy as a rookie at a dance academy school on the first day of lessons. Then, when I came out of the water, I felt like an elephant entering a fine luxury crystal store in Venice. The parasitic twin set I wore on my shoulders reminded me we were in this together, every step of the way.

Finally, we crossed the second siphon, the Yellow one, too short to forget the complexity of the recent past. A new long, dry path awaited us. In the end, when my eyes broke the surface, a masterpiece of nature was painted and sculptured in front of me.

The flow pushed and increased step by step, one moment it was in front of us, the next moment it was at our backs, sucking us down. This dry tunnel is the longest of the caves. You need to be determined if you want to dive the Black Siphon. I walked, hanging my head down, due to my shortness of breath, I have to admit it. Standing in front of the gateway to the Black Siphon was a stunning shallow lake.

A long-flooded tunnel began here, the longest of Romania, more than 400 m/1312 ft. The cave was soft, and the color of the stone was pure black to deep brown. The rocks had the power to absorb the brightness of the diver’s lights. The shape of the tunnel, bottom, walls, and roof change often. Here, nature created a real masterpiece; no artist from the past ever duplicated it.

There’s not a diver in the world who would not be fascinated by the beauty of this particular rock.

The Black Siphon has a section and a profile that shifts quickly; in a few meters, we moved from -7m depth to -42m depth (23 ft-138 ft).Today we spent no more than 40 minutes inside the Black segment of the cave, and it is our goal to return for the next days of the expedition. Finally, it was time to put our fins in the opposite direction. We had a long, arduous journey to get back to the entrance of the cave. All the team members made an “L” sign, which meant time was up. The first day of diving inside the cave was coming to an end.

The second and third siphons had been specular, as well as the dry passages that merged with them.

4.20pm

We had spent more than five hours inside the cave. Not bad as a welcoming dive. When we came out the sun was down, and a pale glaze in the background painted the boundary of the mountains. I was exhausted but pleased about the team’s progress on this first day, and while my face was not smiling, inside I was proud and pleased.

That night while the team slept, I could not. So, I wrote about my memories and kept an eye on the fire, for the heat from the fire warmed not only our bodies but our dry suits as well. Our rural house seemed more like a campsite, and that was all we wished for. For us to be able to share the experience we had today is a gift that none of us will ever forget.

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and CMAS technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor based in North Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming and writings. He holds a Masters degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. Andrea is also the founder of Phy Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching open circuit scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophy of wreck and cave diving. Recently he published his first book entitled, Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti.?