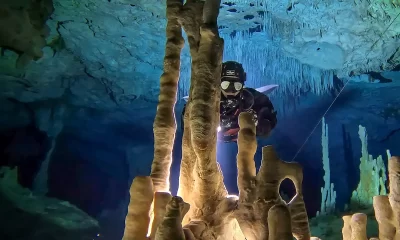

Cave

Incident Report: Lost in a Cave

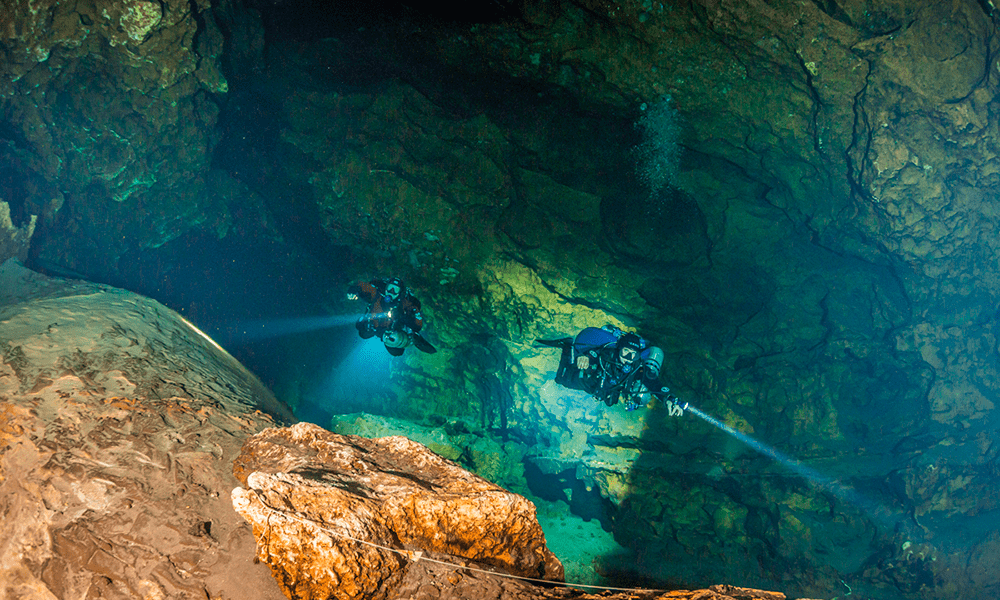

How could four experienced divers get lost in a cave? Human nature got in the way. Human factors pundit Gareth Lock analyzes the factors that led to this “Oh S***” moment and how they might apply to your diving; they are much more common than you think.

by Gareth Lock

Header photo by Kirill Egorov

A team of four divers, all of whom were at least full cave trained, were exploring a cave system in Croatia. The team had already laid a significant amount of line the previous year, and the plan for this dive was to fix and extend the current line and conduct some basic surveying. They also planned to use a novel camera mount to produce 360-degree imagery using multiple GoPro cameras mounted on a special “selfie stick.” Although the maximum depth was 100 ft/30 m, given the length of dive, they would use twin 18s (18 liter tanks) and a stage and scooters. The cave had a small amount of flow but nothing major.

The dive started as planned, and after 30 minutes or so, the divers reached the end of the line and saw the final tie-off from the previous survey and exploration teams. The lead diver pointed to one of the other three to tie in the exploration reel so that they would be ready to explore once the rest of the team had sorted out the camera gear. Due to the complicated nature of the camera and lighting rig, it had been stowed during the long transit to this point. Assuming that the line was being tied in, the other three busied themselves with sorting out the video gear. This process took them approximately three to five minutes to complete.

Once the video rig was ready to go, the lead diver signalled to the team that they would start exploring the cave and shooting video. At this point, the leader noticed that the main reel, which should have been tied in, was still clipped to the first diver’s harness! And because there was a small amount of flow in the cave, and most of the the team had been fixated on sorting out the video rig, they had drifted from the end of the line and were now in the cave without a fixed line to the surface.

They were now 40 minutes into the dive, 100 ft/30 m deep, and had no idea which way was out. Not a great place to be! The lead diver then started lost line protocols, and it took them 15 minutes before they found the end of the line to tie in to and start their exit.

Analysis

As with many incidents, it is easy to join the dots and see why the team ended up in the predicament they did. Hindsight affords us a vision that says “it was obvious it would end up like this.” In this particular case, we can easily surmise that the team members were task- focused, they lost” situational awareness, were complacent, made assumptions, and didn’t close their communication loops. However, all of these negative actions regularly happen on other dives but usually don’t result in negative consequences. That is to say that errors are typically only recognized after something goes wrong!

Many times, we don’t even see errors because we aren’t looking for them; plus they don’t create a negative outcome. If we don’t go looking for near misses by reviewing the situation (e.g., by using a structured debrief), we won’t see how the process had errors or violations within it. Consequently, it is the error-producing conditions we need to focus on, not the (positive or negative) outcome. Losing the line is an outcome; why the divers’ attention was pointed at something perceived to be more important or relevant is where we should be looking if we are to improve safety and performance.

In addition to just noticing the outcome, we are hard-wired to focus on the severity of the outcome. The more the severity increases, the more harshly we judge those involved. For example, would our feelings about this event be the same if the team were working in open water and they didn’t remember to tie in and could ascend straight to the surface? And how about if someone had died because they couldn’t find the original tie-off?

So why did this happen? In this case, the task was novel and challenging and was taking a large percentage of the mental capacity of the divers. The diver who was supposed to tie in was likely more interested in the camera, the lighting rig, and the team rather than the primary task of tying in. Although the tying-in task was important, research on brain activity has shown that when not actively directing one’s attention, humans shift focus between four key categories of information: dangerous, interesting, pleasurable, and important (DIPI). In this example, the camera task/rig was interesting (novel activity, part of a project that was pushing the survey) and pleasurable (surveying new cave, shooting 360 video); consequently, “important” and “dangerous” disappeared down the list of things that were considered worthy of the divers’ attention.

The lighting team would be focused on configuring their rig, thereby reducing their peripheral vision. Being in a cave with bright lights and being mid-water would reduce it further. Peripheral vision is used to detect movement, and this might explain why they missed drifting further into the cave, and so the danger was missed. Even if they had noticed the movement, the working mental model would have been that the first diver had tied in the line, and there was no cause for concern when they saw that first diver again.

Assumptions and miscommunication are commonplace in modern life. In fact, assumptions are essential to operate at the pace we do, since we are unable to consciously process the vast amounts of information that we receive through our sensory systems. In addition to assumptions, a critical instruction was passed (i.e., tie in the line), but the communications loop was not completed. The leader should have ensured that the tie-in had started before the team began working on the video rig.

Applying these Lessons to Your Diving

The Limitations of Situational Awareness. If we don’t want to be distracted at the wrong or critical time, we need to understand how our attention system works. We have a finite capacity in our working memory, shown to be seven +/- two elements of information at any one time. Note that this is “elements” and not “pieces” of information, a critical distinction when it comes to improving situational awareness and mental capacity.

As we become more skilled at an activity, we start to chunk information together (e.g., when we first start to dive, we have to actively think about the sequence of activities to stabilize at a stop). These might be: look at the computer/timer, note that we are 3-5 ft/1-2 m below the stop depth, reach back and grab the OPV dump cord (or inflator hose), pull the cord (press the deflate button), monitor how much gas leaves the wing (or the time the button is pressed/cord pulled), and watch the computer to see where we are. Unfortunately, we often don’t get it right, either stopping too soon or too late, and then start to oscillate around the stop depth.

However, when we are more experienced, the activity of arriving at a stop combines all these actions into one “element” that we don’t actively think about, and we get it right the first time. This means we have more capacity to see what else is going on around us and to anticipate what might happen next. The same goes for other technical skills that need to be developed.

Definition of Error. Divers have a vested interest in making sure that they make a decision that ensures that they (or someone else) doesn’t die or get injured. As such, if a diver knows with 100% certainty what the outcome is going to be, and it is a negative outcome, they won’t execute that decision. Errors happen all the time, but not every error ends up as an incident or accident. If we want to improve our safety, we need to invest time to review what we’ve just done and not just the outcome. Ultimately, we need to understand how it made sense for those involved.

Like incident reports? Read another.

Header photo by Kirill Egorov.

Gareth Lock is an OC and CCR technical diver with the personal goal of improving divingsafety and diver performance by enhancing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards human factors in diving. Although based in the UK, he runs training and development courses across the globe as well as via his online portal https://www.thehumandiver.com.He is the Director of Risk Management for GUE and has been involved with the organization since 2006 when he completed his Fundamentals class.