Latest Features

Improving Rebreather Safety: An Aviation Safety Professional’s Take

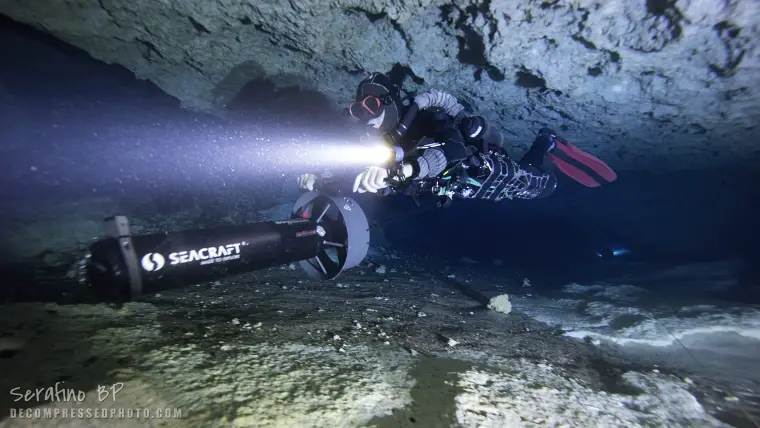

Rebreather diving safety arguably remains a work of progress in the technical diving community. Since Rebreather Forum 3, held in 2012, we have lost at least 293 rebreather divers, and unfortunately, there does not seem to be a systemic, and or easily-identifiable set of causes, nor a simple fix. Special Operations Instructor Pilot, Flight Safety Officer and tech rebreather diver Serafino Bohrer-Padavos proposes that we look to the US Aviation industry for answers. Fasten your seat belt and hang on!

Text & images by Serafino Bohrer-Padavos. Lead image: Michal Turek and Brent Kiomall pose before a sunset dive.

Rebreathers have broken out of the military and commercial diving communities and are redefining how civilian recreational and technical divers explore the underwater environment. These machines offer extended bottom times, silent operation, and the ability to push past the logistical limits of open-circuit diving. No longer reserved for elite military teams or high-budget expeditions, rebreathers are now in the hands of divers pushing deeper into caves, reaching new depths, and experimenting with novel gas mixtures. These advancements are all made possible by the unique advantages of rebreather technology.

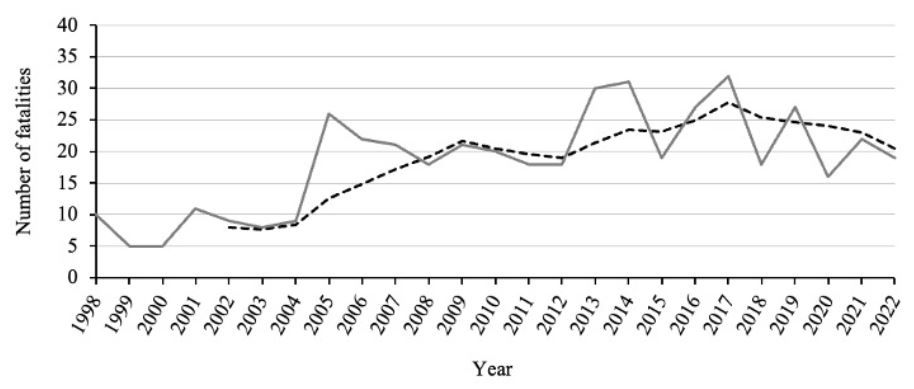

With this great potential comes greater complexity and risk. Worldwide, between 2012 and 2024, it is estimated that there were at least 293 deaths of sport divers on rebreathers. Currently, it is estimated that there are two to four deaths per 100,000 rebreather dives, or about 1-2.5 deaths per 100,000 hours on a rebreather, which is roughly 10 times higher than that of open circuit diving (Fock, 2013, Tillmans, 2024).

Using these annual fatality rates, which result in about 20-30 deaths per year, rebreather diving carries approximately 10x the risk of skydiving, though it’s less risky as base jumping (Tillmans, 2024; Fock, 2013). The exact causes of these deaths are topics of debate and will likely never be solved. Accident analysis is limited for this activity, reporting regulations are sparse or non-existent, and much of the lifesaving data from accidents are lost with the divers who perished. As a result, the safety system surrounding rebreather use appears to have its own inherent problems.

Today, we stand at an inflection point in rebreather history. As our community continues to grow, we have an opportunity to close the gaps in training, unify standards, refocus on building diver competency, and, most importantly, create a safer system. Unlike open-circuit systems, where a diver can get away with being a little lackadaisical, and/or distracted, rebreathers demand a different level of discipline and awareness.

I like to think of an open-circuit system as a smoke alarm: It’s loud, obvious, and almost impossible to ignore when something goes wrong. A rebreather, on the other hand, is subtle, sophisticated, and silent: It’s not going to ask you to wake up and pay attention. If you stay vigilant and follow procedures, chances are that you’ll be fine—but look away too long or get complacent—and there might be dire consequences.

To safely operate these complex machines, it requires an understanding of chemically reactive oxygen sensors, physiological effects, and failure points that aren’t just theoretical—they’re life or death. It also requires distinct awareness of one’s own limits and weaknesses along with a degree of humility. As the late US Navy’s chief diving medical officer Dr. Ed Thalmann once observed, “The scuba regulator is the steam engine of diving. It’s been around a long time. They’ve been honed to a fine art and they’re incredibly reliable. By comparison, a rebreather is like a space shuttle!”

Complexity in every aspect means that rebreather divers need meticulous maintenance habits, methodical training, and a level of system knowledge that I believe most current certification courses just don’t adequately reinforce. You must also be keenly aware that you are human and, as such, are prone to making mistakes.

Intensifying these issues is the lack of uniformity in training standards across agencies. Different agencies teach skills at different times and in different courses. Each instructor is unique; this inherently leads to differences in the enforcement of standards. These differences can lead to gaps in knowledge of material assumed to be previously covered which could be vital to a technical diver.

Compounding this issue is the lack of unified enforcement of standards. While most technical instructors operate in good faith and will not pass a student who doesn’t meet standards, there are some who are rumored to be less scrupulous. These bad actors are able to operate dishonorably because of an imperfect system—one that could and needs to be improved.

As technology advances and more divers make the transition to rebreathers, the need for high-quality training is urgent. Certifications must represent genuine competence and not just a free pass to a dive site or equipment. Our diving community must act now and quickly to ensure the success of our sport, our industry, and our passion.

The Challenges of Self-Governance

Unlike commercial diving, the sport diving industry is exempt from workplace regulations such as those enforced by the Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) in the US, and the Health & Safety Executive (HSE) in the UK. There are very few countries in the world that litigate how sport diving shall be conducted. Instead, the industry is for the most part self-governed.

As a result, the dive industry determines which certifications and certifying agencies to accept as credible. Recognition of any certification’s validity is community-dependent and notoriety based. There is no legal requirement to have a dive certification to strap on a scuba tank and dip below the surface. Typically, the only thing stopping a non-certified individual from diving is a dive shop refusing to rent out gear or to fill up a tank. By not condoning or supporting untrained divers, the dive operator remains relatively safe from legal harm.

It’s important to acknowledge that, as proprietors in a market, dive instructors are motivated financially. This can put them in a tough spot: If they fail a student, they can lose money and, possibly, future business. If they pass a student who does not meet standards, they risk liability. Even though most instructors uphold the standards, all it takes is one or two who do not, to endanger divers and the industry as a whole. I will go as far as to say that even good instructors are fallible, and no one can make truly impartial decisions.

They are also not robots: They have an inherent bias and will respond to internal and external pressure. In my opinion, this innate human nature (along with rare cases of intentional neglect) is watering down the level of competency in rebreather divers. While many divers receive exceptional training, some do not. This is not a problem unique to diving; it is just that our diving industry is not yet equipped to deal with the problem.

Looking Up

Now look at a similar community, but one with extremely tight regulatory oversight and strictly enforced standards. The world of aviation, which has been around much longer than diving, arguably learned its lessons, and is widely looked upon as a gold standard of safety and regulation. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) sets strict regulations for training, proficiency, and equipment, and upholds stringent certification standards to ensure aviation safety and competence. There is a structured approach to the human and the hardware.

Aircraft Inspections: In order to maintain a status of “airworthy,” the FAA has mandated rigorous and regular inspections for aircraft: both pre-flight checks performed by the Pilot-in-Command and annual inspections since 1926. Commercial operators incur additional oversight, including phase and progressive inspections. These inspections ensure that the aircraft is maintained properly and is in a condition that is safe to fly without causing undue risk to the occupants or bystanders.

Design Criteria: Aircraft must meet strict design criteria to pass certification standards set forth by the FAA. A classic example of this is that gear handles are required to appear and look like a wheel, while flap handles are required to resemble a flap. This came about during WWII as pilots kept accidentally raising the gear while taxiing when intending to raise the flaps. This happened because, at the time, the two handles were identical! Another great example is the color coding of fuel: Avgas is colored blue so as to be easily distinguished from water or jet fuel which could cause an engine failure if used in the wrong engine. By checking the color of your fuel, you can determine if it is the correct fuel for your aircraft and if any water has seeped in. Aircraft systems are regulated to maintain failsafes and backups, they are designed intuitively, and they are rigorously tested to ensure no part compromises safety.

Required Training Hours and Events: Before taking a practical flight test, pilots must complete a specified number of training hours which vary based on the certification sought and ensure comprehensive skill development and preparedness for the practical test.

Written Examinations: Prospective pilots begin with comprehensive written tests covering aviation regulations, aircraft systems, navigation, meteorology, and flight planning. These exams require extensive study to master the topics covered and it is akin to studying for a final exam covering material from multiple courses at a college level.

Practical Flight Tests: Following the written exams, pilots undergo practical flight tests administered by FAA-designated pilot examiners. These are third party examiners—not the instructor who has prepared the student. An instructor’s reputation (and, in some cases, their ability to maintain their instructional ability) depends upon only recommending students who can pass the practical test, conducted in an aircraft or simulator. The aim is to test and evaluate a pilot’s ability to operate safely under various conditions and handle emergency situations.

Type Ratings and Endorsements: Pilots aiming to fly specific and complex aircraft types, such as jets or commercial airliners, must obtain type ratings. This process involves additional training and proficiency checks focused on the unique systems and characteristics of each aircraft type. Certified flight instructors or examiners provide endorsements upon demonstrating proficiency.

Continuing Education and Proficiency: The FAA emphasizes ongoing education and proficiency. Recurrent training and proficiency checks are mandatory to maintain the privileges of certifications, ensuring pilots remain current with technological advancements, regulatory updates, and safety protocols.

Safety Oversight and Compliance: The FAA maintains strict oversight to enforce safety standards across aviation operations. Inspectors conduct regular checks on pilots, aircraft, and aviation organizations to verify compliance with regulations and identify potential safety issues. It is possible to be reported to the FAA for investigation based on complaints, Air Traffic Control reports, and other data sources.

International Collaboration: Internationally, the FAA collaborates with aviation authorities to harmonize safety standards and operational practices. The precedent for international collaboration was set in the Chicago Convention in 1944, which was fully enacted in 1947. This alignment promotes consistency in safety measures and enhances global aviation safety. There is global recognition of FAA certification and the means to operate safely worldwide in an international airspace system. This is possible due to the collaboration and agreement on standards pertaining to pilots of all levels.

Accident Investigation: In aviation, every accident or incident, no matter how small, triggers a systematic inquiry that is tailored to the severity of the occurrence. Each incident or accident is required to be reported immediately to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) and subsequently delegated to the FAA if appropriate. In the case of a major accident, the NTSB painstakingly collects mountains of information in technical data, maintenance records, and pilot logs before conducting a forensic analysis of the accident site and aircraft.

Their findings pinpoint the root cause and contributing factors. These findings lead to recommendations of policy changes and industry practices. This data, as well as lessons learned, are stored in a public database for all to benefit from. This comprehensive, independent analysis ensures continuous improvement in aviation safety—and ultimately saves lives.

The Dive World In Comparison

Equipment Inspections: Unlike aviation, diving does not mandate equipment inspections, and there is no mandatory maintenance required (although highly advised) for your rebreather. Conscientious divers and instructors perform regular checks, and some may send their units in for service annually, or as recommended per the manufacturer, but there is no universal requirement for periodic inspections. Without formal inspection protocol, unsafe gear can go unnoticed for long periods of time until the failure becomes catastrophic.

Design Criteria: Diving equipment, specifically rebreathers, lack a standardized design. While the components generally hold consistent across models, there are no cross-manufacturer design conventions. Shapes and colors are not standardized, tactile feel is inconsistent, and alarms vary between models of controllers/monitors. A great example of this is the way in which Partial Pressure of Oxygen (PO2) is displayed on a heads-up displays. Some models use a blinking light of varying colors where the flashes count the PO2 in tenths, and others can be set to a simpler green = setpoint. These inconsistencies, as well as various human factors considerations, lead to increased diver workload and risk to the operator, especially when handling an emergency.

Required Training Hours and Events: Dive training agencies adhere to minimum hours/dives in writing. However, in my 17 years of diving, I have never had an instructor check my logbook to determine if I had the requisite number of dives prior to beginning advanced training. (This is across multiple dive agencies and instructors.) Most agencies do require a minimum bottom time per class—which is a step in the right direction. The best instructors I have had far exceed the minimum times in order to sufficiently cover the skills; many do not.

Written Examinations: The written examinations in the dive world pale in comparison to those in aviation. Question banks consist of 20-50 questions that rarely vary. This reinforces the instruction on only a small number of topics and does not do a sufficient job ensuring students truly understand and can apply the knowledge needed to conduct their diving safely. In contrast, FAA examinations come from a randomized question bank consisting of hundreds, sometimes thousands of questions which require true understanding and mastery of the material to answer correctly.

Practical Tests: Check-rides do not exist in diving. Your final dive consists of a training dive. There is no impartial examiner to observe your skills, your planning, or your ability to dive independently and safely. While some agencies have a more robust validation process than others, there is no impartial third-party judge to determine a student’s mastery of skills and adherence to strict objective standards.

Type Ratings and Endorsements: To again draw on the parallels to aviation, it would be as if you needed a new type rating (certification) to fly an aircraft with a different model of engine or seating arrangements. That is the case with different rebreather models. In other words, I believe that there exist far too many individual rebreather certification courses instead of a few comprehensive system-level courses. Knowledge needs to be much more generalized to encompass the underlying principles of diving on a closed circuit rebreather. These principles must be internalized and mastered. A student must be able to apply these skills to a variety of situations and units. Training a diver to think about and understand what they are doing arms them with the tools to survive life-threatening situations.

Continuing Education and Proficiency: For some agencies, the primary motivation for instructors is to continue their education in order to be able to offer more classes, and to sell more certifications. Student divers are motivated by being allowed by the dive operator to conduct dives. There are no proficiency checks and, at many agencies, dive certifications are good for your life. There are divers who return to diving over 20 years after certification with no dives since their class. In an ideal world, these divers would be stopped by the dive shops. Instead, the certification card provides peace of mind that, if anything happened, the shop’s insurance would likely cover it.

This lack of a formal recertification process in rebreather diving arguably poses a notable risk to diver safety. The technology and best practices in rebreather diving are continually evolving. Re-certification processes could ensure that divers stay up-to-date with the latest advancements and safety protocols, and enhance preparedness, thereby reducing the risk of incidents in this high-risk activity.

Safety Oversight and Compliance: There is no oversight except in the rare circumstances when a student, or an instructor, reports an instructor to their respective dive agency. There is no formal, industry-wide protocol for divers to report their peers for violating protocols, standards, or just general safety guidelines. There’s no guarantee that agencies will take appropriate actions when divers do report their peers for violating safety protocols. There is no SCUBA police (nor am I recommending one).

International Collaboration: Most dive agencies are recognized worldwide. The International Standards Organization (ISO) contributes to a universal set of certification standards. However, the ISO has no legal foothold nor does it provide any sort of official recognition of complying parties. An individual can create a diving certification agency with their own certification standards. The only verification is community-based credibility and recognition by individual dive operators.

A Further Note on Training

The current state of rebreather training is such that you can arguably find two divers with the same certification but with very different levels of skill. Some agencies are trying to tighten standards but, in the process, they’re making training more expensive and less accessible. For example, the requirement that every distinct rebreather model requires its own certification course versus a systemic rebreather course valid across models, and the stipulation that instructors train on the exact same unit and configuration as their students, arguably makes rebreather instruction even more fragmented.

Though these requirements sound good in theory, in reality, it makes the instructor pool smaller, limits accessibility, and doesn’t fix the underlying problem—inconsistent training and lack of enforcement. Jeff Bozanic does an excellent job of addressing this issue in his InDEPTH article, “Rebreather Training: Are We Certifying Ourselves into Extinction?”

Toward a Safer Future

To enhance safety and standardization in rebreather diving, several key reforms are necessary:

Unified Standards:

Development of Industry-Wide Standards: The creation and adherence by all dive agencies to a set of uniform standards will significantly enhance safety and consistency. As of today, the ISO has standards developed for rebreather instruction. These standards are based on recommendations from the Rebreather Training Council (RTC) and Rebreather Education Safety Association (RESA), among others (Caney, 2023). However, the standards are voluntary and address only training standardization, not design or diving operations.

Developing a comprehensive set of design guidelines that apply to all rebreather models is needed, reducing the need for type-specific certifications. For example, a standardized manual addition valve with a specific texture and shape and color could do wonders for safety—akin to what the gear and flap handle have done for aircraft.

Just as important is the voluntary adherence of dive agencies to these standards. Some organizations have modified their training to conform to the ISO standards, but the lack of adherence by others has slowed the community’s progress toward uniformity.

Promoting Interoperability: Standardized protocols across dive agencies and similar component designs help ensure that divers can seamlessly transition between different rebreather models. This will not only improve safety but will also make it easier for divers to adapt to new equipment without needing extensive retraining.

Enforcement of Training Standards:

Accountability for Instructors: Instructors play a crucial role in ensuring that divers are properly trained. By holding instructors accountable for adhering to consistent training protocols, we can maintain a high level of proficiency among certification holders. Training agencies need to have a system in place that rewards strict adherence to standards and remediates the deviation from them.

Uniform Standards of Proficiency: Establishing a universal standard for what constitutes adequate training and proficiency, agreed upon by all agencies, will ensure consistency among divers. This approach guarantees divers possess the same skills and knowledge to dive safely, regardless of where or with whom they trained.

Recertification Requirements:

Periodic Recertification Processes: Introducing mandatory recertification processes will ensure that divers regularly refresh their skills and demonstrate ongoing competence. This can be achieved through scheduled proficiency checks and skill refresher courses.

Market Growth through Recertification Dives: By making recertification less unit-specific, the market for rebreather diving can expand. A rebreather instructor can offer refresher courses to a larger market with a new need to provide them. This approach allows divers to maintain their certification through regular practice without imposing unnecessary restrictions on the quality of instruction for non-unit-specific courses.

Regulatory Oversight:

Advocacy for Independent Bodies: Similar to the aviation industry, establishing an independent body with the authority to oversee rebreather diving and training [Ed.note: A Rebreather Training Council with teeth?] could provide the backbone for enforcement. An independent body could ensure compliance with safety standards and proficiency requirements. This regulatory-like oversight could provide an additional layer of safety and, more importantly, a much-needed layer of accountability.

This body could sponsor agencies independently and approve them as compliant organizations, sanctioning them as approved agencies. Take the notoriety out of certification recognition and make it official. This would operate similarly to how other third-party verification organizations operate, such as for dietary supplements which are not subject to regulations of the FDA in the U.S. Organizations exist that verify the contents and claims of these supplements that consumers purchase and provide an official approval for reviewed products. This could be adapted for diving, a seal of approval from a third party and independent dive training review agency.

Ensuring Compliance: Regulatory bodies can conduct regular audits and inspections to ensure that both instructors and divers adhere to the established standards, further enhancing the overall safety of the activity.

Maintaining Generic CCR Courses:

Support for Advanced Non-Unit Specific Courses: Offering advanced level courses that are not tied to specific rebreather units can keep the market open and accessible as Jeff Bozanic proposed in his article. Better training is better training—not more training. Advanced courses rely on a solid understanding of closed-circuit principles, skills, and competencies. What applies to one rebreather model, in general, applies to another.

In addition, generalized training would not further limit the access to instructors that best meet the needs of their students. This approach ensures that instructors can continue to provide high-quality training to students receptive to their instruction, even as the demand for advanced training in mixed gas or overhead environments remains limited.

Market Sustainability for Instructors: By maintaining a broader market, instructors can conduct training more frequently which helps them stay sharp and deliver better instruction. This benefits both the instructors and the divers, as it ensures a higher standard of training.

Accident Investigations

Shortcomings: In contrast to aviation, the diving community has no standard of reporting or investigating dive incidents or accidents. If there is a death on a rebreather, there is no independent body to swoop in, collect data, and perform an analysis. The best we hope to achieve is through small agencies such as the International Underwater Cave Rescue and Recovery (IUCRR) non-profit which publishes some investigations that occur in the overhead environment. While I am personally a fan of the efforts of the IUCRR, these members are skilled divers, but not necessarily trained or equipped for proper accident analysis and documentation. In addition to the lack of analysis, there is no universal accident database to compile common causal factors and determine the greatest risks to divers who use rebreathers.

Towards a better future: Again it is necessary to have a third-party involved. In this case an investigative organization should be formed immediately. A standardized, objective, and widely accessible reporting system of formal accident analysis is crucial to understanding the risks involved. This could lead to changes in rebreather design, training, education, and practice. We need to follow the models of aviation and report our accidents and incidents. This idea is nothing new: It was proposed at Rebreather Forum 3 by Dr. Fock, yet nothing has been done (Menduno 2021). It is imperative that we foster a safety culture, one in which we report our mistakes so that we can make proactive risk management decisions and enhance overall diver safety.

The Bottom line

Rebreather diving represents the cutting edge of technical diving and will continue to grow. However, given the current fatality rates, we arguably need to make changes in rebreather training and safety protocols. If we want to make diving safer, more accessible and grow our industry, change must happen soon. If we apply even half of the principles that the aviation industry operates by to diving, we’d be in a much better place.

Now is the time to take real steps toward improving training, enforcing standards, and making sure divers are equipped with the requisite knowledge to safely perform their dive. At the end of the day, the water you’re diving in doesn’t care how many certification cards you have; it only cares if you’re capable of surviving the dive. We need to act now by discussing these issues as a community to gain the necessary momentum for action. We need to change!

References

Fock, A. W. (2013). Analysis of recreational closed-circuit rebreather deaths 1998-2010. Diving Hyperb Med, 43(2), 78-85.

Tillmans F. (2024) Closed-circuit rebreather accident review-the safety situation. In Pollock NW, ed. Rebreather Forum 4. Proceedings of the April 20-22, 2023 Workshop. Valetta, Malta 2024; 45-56

Tillmans, F. (2023). The safety situation in rebreather diving: An analysis. GUE.tv.

Menduno, M. (2012, May 10). Improving rebreather safety: The view from Rebreather Forum 3. InDepth Magazine.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: The Case for an Independent Investigation & Testing Laboratory by John Clarke

InDEPTH: Has Rebreather Diving Gotten Safer by Ashley Stewart

Serafino Bohrer-Padavos is a cave diver, hypoxic trimix rebreather diver, and an underwater photographer who spends his time exploring, learning, and trying to keep himself and others from making fatal mistakes. Outside of diving, he’s a Special Operations Instructor Pilot and Flight Safety Officer where he focuses on risk management, mishap investigations, trend analysis, and making sure small errors don’t turn into major consequences. He doesn’t claim to have all the answers, but experience has taught him that, whether in the sky or underwater, cutting corners and bad training gets people killed.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are his own and do not reflect the official policies, opinions, or positions of any organization, agency, or employer he is affiliated with.