Latest Features

Imagineering The Future of Diving

Whether it’s mixed gas technology, rebreathers, diver propulsion vehicles, or saturation diving, the US Navy has consistently led the way in extending our underwater envelope. The tip of the spear? It’s the Navy’s nearly 80-year-old brainy powerhouse, the Office of Naval Research (ONR), which is currently busy imagineering and funding the future of diving, as bioengineer Rachel Lance explains.

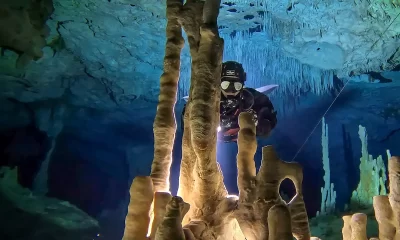

By Rachel Lance. Lead image: A military diver wearing a JFD Shadow rebreather and a mask with a heads-up display, a technological innovation that was the product of the Office of Naval Research (ONR) and military engineers. Photo courtesy of JFD. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

The US Navy has the best dive toys. From advanced thermal gear made from materials invented for NASA, to heads-up displays with silt-penetrating underwater night vision, US Navy divers are the recipients of tech we all want to own (or at least play with). But where does that tech come from? Good undersea inventors are hard to find, and there are few, if any, with the resources to undertake such intense projects without help.

The answer—the driving force behind many ocean-related “eureka” moments past, present, and future—is a specialized United States government department called the Office of Naval Research. Abbreviated ONR, the agency falls under the aegis of the Secretary of the Navy and is headquartered inside a glass-walled rectangular building in the vicinity of the Pentagon. ONR’s employees, a large fraction of whom are scientists themselves, are charged with identifying promising ideas from experts around the globe who might expand what we are able to do in the water— then, critically, also funding the research to help those ideas happen. These employees number roughly 3,800 and are spread between ONR headquarters, the affiliated Naval Research Laboratory, and ONR Global branches that reach 55 countries.

A portion of the logo for SCOUT, an ONR program to find new solutions for the U.S. Pacific Fleet (PACFLT)

The research they want is at an early stage. It’s ONR that provides the fuel to ignite the wilder ideas of the undersea world, the ideas so crazy they just might work. When we’re lucky, they do.

Wartime Roots

Like many of the best and worst ideas of humanity, ONR has its roots in war. At the start of World War II, the United States and other Allied countries underestimated the knowledge gap between building a submarine and using one in a way that was safe for the crew. In the 1930s, while Hitler rumbled, a disastrous series of sinkings shocked them awake to their need for more science.

The American S-4 sank in 1927 with the loss of all crew, and the tragedy sparked initial work in submarine escape. However, in the summer of 1939, within a span of twenty-three days, the USS Squalus, HMS Thetis, and French Phénix went down in training accidents. While some crew members were rescued and others escaped from the Squalus and Thetis, their near-death states of health and the unexpected problems encountered during the operations smacked the three navies with the realization that surviving underwater without an air supply umbilical was harder than they assumed. They needed more experts from a broader diversity of fields, including physiology, to develop solutions that worked better.

Experimental diving equipment on a pier in Fort Pierce, FL in 1944. This gear appears to have been made from modified mine rescue equipment. Image: Naval History and Heritage Command 80-G-264541

A diver, likely a member of the Naval Combat Demolition Underwater (NCDU) teams, with an experimental breathing apparatus entering the water at Fort Pierce, FL in July 1944. Image: Naval History and Heritage Command 80-G-264549

Then, with the fall of France in early 1940 and Spain claiming neutrality but leaning German, the European continent developed a full perimeter crust of Nazi forces. To stop the Nazis, the Allies would have to break through that crust from the ocean before they could send troops across Europe on land. And all previous such amphibious efforts had failed.

Their scientists got to work. Christian Lambertsen (1917-2011) began pitching his homemade oxygen breathing apparatus for free-swimming diving underwater. His British counterparts in London began testing modified Siebe Gorman submarine escape devices on themselves for the same reason. Jacques Cousteau was working on the first regulator prototypes at the same time, but was locked inside occupied France. At first, neither the US nor the Royal Navy was interested, but as the war raged on, they began to turn their heads to the utility of undersea warriors. The US Navy started the wartime Office of Scientific Research and Development to organize funding for ideas they needed in a frenzy.

Dr. Christian Lambertsen receiving an award for service from The OSS Society in 2009. Photo courtesy of The OSS Society.

In the words of post-war Assistant Secretary of the Navy Garrison Norton, “The government until World War II had never seriously gotten into the research business.” But, under the barrages of German U-boats, they realized the utility of being able to guide the direction of invention. The world of diving still benefits from that decision. Quickly, the Navy researched (then issued) guidance to the fleet for how to modify gas masks to turn them into diving rigs.

Lambertsen wearing his device, the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit (LARU) in 1940. Image: USPTO

Early Naval Combat Demolition Underwater personnel toyed alongside their recruited scientists and engineers to hand-make early prototypes for free-swimming underwater breathing apparatuses: apparatuses they would eventually use along Lambertsen’s rig to dismantle Nazi oceanic defenses. Researchers pivoted early naval work into the utility of the atom, which they’d wanted as a fuel source for ships, and it became part of the Manhattan Project. It seemed like the days of scientists sitting in their ivory towers, isolated from their end users, were over.

However, at the end of the war, as the urgency of combat dissipated, the push for cooperation between researcher and end user did, too. The researchers and the goals of the Navy drifted apart again, and it seemed things were going back to the way they were. Until a few in the Navy decided not to let it.

After a brief stint named the Office of Research and Inventions, ONR was formalized by an act of Congress less than a year after the end of the war in August 1946. Their charge was “to plan, foster, and encourage scientific research in recognition of its paramount importance as related to the maintenance of future naval power.” ONR was set up to enable work, research, and invention during peace so that, once an emergency occurred, US Navy personnel—including divers—already had the tools they needed. The new office wanted to keep the scientists voluntarily incentivized through funding to stay focused on the end users.

At a ten-year anniversary meeting with its founders, the fledgling ONR of 1946 was described as the first and only organization in the US federal government “that was equipped to deal with science.” ONR stood alone in its goal of research tied to practical capabilities, and its skeptics were many. But within a few years, ONR funding and oversight led to a “dog tag” radiation dosimeter that could be worn by troops concerned about Cold War fallout, radio echoes were taken from the surface of the moon that would help plan the eventual landings, and new methods of preparing skin for grafting let it be stored at room temperature, shipped, and even stockpiled. The US Navy pivoted atomic research back, and became the first to use nuclear power for a practical purpose in their ship engines. The skeptics fell silent.

Engineer Jeffrey Phillips of the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC) tests their novel ONR-funded invention for monitoring diver health through eye motions in one of the research hyperbaric chambers at Duke University. Image: Courtesy William Howell

A Pipeline for Ideas

Today, ONR’s mission remains facilitating work that lets naval personnel do their jobs better and more safely, and that includes the divers. Dr. Sandra Chapman, PhD is one of 117 program officers at ONR, and she is the current lead Program Officer for the Undersea Medicine and Performance and Marine Mammal Health divisions. [Ed. note: Chief Imagineer!] She has been in the post since 2018 and, therefore, she is the grand wizardess with her finger on the pulse of early diving research. Her job, as she sees it, is to use ONR’s resources to “create a healthy pipeline” for ideas, and to be a good steward for the needs of the Navy’s elite diving groups. She describes ONR’s mission as “being creative” and finding (then funding) “novel approaches and solutions” to the military diving community’s problems.

Dr. Sandra Chapman encourages young innovators to “keep asking questions” at a STEM outreach event for high school students in Virginia Beach, VA in 2023. Chapman considers STEM outreach a key goal for ONR. U.S. Navy photo by Michael Walls, via DVIDS

Applications for funding are open to all; and, in their search for creativity, ONR publishes a yearly Broad Agency Announcement, BAA that lists what they want to achieve rather than how they want the tasks done. Applications start with a brief whitepaper including a rough budget, and if their board of reviewers think the concept has merit, they will invite the applicant to send a more detailed full proposal. If the funds are granted, the recipients get an opportunity to provide a new solution to the military diving world.

Those solutions, thankfully, then often trickle outward into the hands of civilians, too. Ideas that show promise at the end of their project cycles are transitioned. Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) is a second organization that walks closely side-by-side with ONR, and they seek to develop the most promising concepts into practical tools that can be manufactured and used in the field.

If an idea is also marketable, the researchers and the US Navy may partner with commercial companies for production, and these companies are allowed to sell related products to the rest of us. The Oceanic DataMask, for example, was originally developed as an internal US Navy project with civilian naval engineers, ONR, and NAVSEA.

The Navy’s engineers also did not stop with a half mask. The same expertise got rolled into another type of heads-up display called the Diver Augmented Visual Display, DAVD. The DAVD provides high-resolution SONAR images of the water surrounding a diver, which has obvious utility to anyone ever caught in zero-visibility conditions. That tech, too, is now available for purchase through Coda Octopus. And the new toys have made an impact.

An engineering team from IHMC stands by the control panels at Duke University’s hyperbaric chambers in 2022. Dr. Rachel Lance and Sarah Piper, then researchers at Duke, brief the team at the start of an ONR-funded project. Image courtesy William Howell

“DAVD is a game changer,” said Master Chief Master Diver Joshua Dumke. When the fires occurred in Maui, DAVD was used by bottom plodding hard hat divers to find and pinpoint the precise geolocations of twenty-six boats that were missing—each of which was suspected to have human remains inside. Because of ONR, NAVSEA, and DAVD, families knew where their loved ones lay. When the Baltimore Bridge collapsed, DAVD was used similarly to map all the wreckage, providing a detailed underwater map so workers could create a plan to start the recovery.

DAVD can penetrate silt, even in blackout conditions and at night. The system is designed for hard hats now, but it is a reasonable jump to think that it could be transitioned to a tool for cave and wreck divers in emergencies.

Making Divers Safer

Getting funding from ONR or NAVSEA also means a researcher is about to be tapped into the needs of the diving community in a way that is otherwise not possible, especially not from an ivory tower. Once a year, the two agencies host a meeting they call Program Review, and attendance is required for every head researcher who takes their money. For three days each spring, they shove each one of us in a conference room that is inevitably freezing cold, and we get twelve minutes per each of the roughly 60-80 projects happening amongst the two agencies to tell the entire community what we’ve done. In 2023, we heard talks about novel ways to build single-atmosphere dive suits, probabilistic DCS modeling, harvesting oxygen from seawater, and more. (Abstracts of the talks, by the way, are publicly available online.)

IHMC engineer Connor Tate looks at the photographer while testing novel equipment she helped design to monitor diver health and function during a dive. Image courtesy William Howell

In my opinion, it’s the best week of the year for a dive researcher. The meeting location rotates, but wherever it is, that one room contains experts in every aspect of underwater survival ranging from tiny particulates and human microbiology to pressure-resistant advanced materials. Since a presentation is mandatory each time regardless of how complete the work is, it’s the cultural norm for us to talk about our failures as well as our successes, the things we worry about in addition to those we have conquered; it’s also an opportunity to ask for help from the others present.

Between talks, we drink coffee, try to warm our hands, and concoct new ideas with those whose brains can fill the expertise gaps inside our own. Mixed in with the group are always one or two dozen personnel in uniform as well: personnel who are either researchers themselves while on active duty or are high-level representatives in the military diving community. That second category comes to make sure we’re staying focused on something they and their divers could practically need. The mixture means that if we have a question about a type of diving we’ve never done, the answer is as simple as turning to the person in the next chair over. At the end of the meeting, we leave re-energized and ready to keep pushing diving forward.

Prototype heads-up display glasses of the DAVD system seen installed inside a diving helmet, and ready for use, during the device’s development in 2018. Photo by Jacqui Barker via DVIDS

We also leave reminded of ONR’s goal and why they fund us: to make diving safer. The current wishlist of Chapman and ONR’s Undersea Medicine group gets reset every few decades through a careful survey of fleet needs, and the current one, set in 2006, reads like a dream journal of every tech diver in the world. For example, “figuring out the inflammatory response to DCS” is a major goal of hers, she says. She particularly wants to understand why the dread affliction has so much individual variability because, maybe from that variability, we will be able to identify some things we can administer as prophylactics to reduce the odds it will strike.

Chapman and ONR are also interested in diving in contaminated water, oxygen toxicity, hypercapnia, hypoxia, and the usual suspects that cause diving fatalities not just for the US military but for divers around the world. That’s why they stay tapped into those communities, too. The list is broad—including aspects of the underwater world from submarine escape to things like breath-hold diving, rebreather scrubber materials, and cold protection—on purpose to allow creatives from all sorts of fields to be considered eligible for application, so long as they might solve a problem in diving.

Prototype ONR-funded diving equipment sitting on a table while its custom software is checked and validated by IHMC engineer Savannah Ripley before the device is used in an experiment. Image courtesy William Howell

While writing this article, Chapman and other ONR personnel popped up in the participant list of a Zoom organized by InDEPTH chief Michael Menduno and military advisor Vince Ferris. The goal of the meeting was to bring together scientists, engineers, and physiologists from across all the realms of the underwater world to talk about how we can better support each other past the obstacles between idea and physical product for diver sensors, much like a smaller and self-organized version of ONR/NAVSEA Program Review. The meeting had enthusiastic representatives from the US Navy’s internal researchers, academia, Divers Alert Network, and the civilian diving and manufacturing industry. Chapman and the ONR personnel signed in because, as usual, they were ready to help create a pipeline of ideas.

DIVE DEEPER

US Navy Research: Undersea Medicine with Dr. Sandra Chapman (video). Dr. Sandra Chapman’s ultimate work goal is to turn mere mortals into Aquaman! How’d you like to have a pair of gills to go swimming? Dr. Chapman plans to make this a reality!

GUE.tv: Rebreather Forum 4 presentation—Near Future of Physiological Monitoring by Rachel Lance

InDEPTH: Scientists That Operationalized Self-contained Diving Book excerpt by Rachel Lance, PhD. Interview by Michael Menduno

Alert Diver: Deep in the Science of Diving (A profile of the US Navy’s Experimental Diving Unit) by Michael Menduno

Wired: They Experimented on Themselves in Secret. What They Discovered Helped Win a War by Rachel Lance

The untold, top-secret story of the British researchers who found the key to keeping humans alive underwater—and helped make D-Day a success.

Wired: How to Escape From a Sunken Submarine by Rachel Lance. First of all, you can’t just open the hatch when you’re trapped at the bottom of the ocean. But there is a way out—it requires physics and some audacity.

Rachel Lance, PhD is a biomedical engineer who studies the physiology of survival underwater and in other extreme environments, often with a focus on improving survivability through engineering innovation. Until recently, she worked as research faculty at the Duke University Center for Hyperbaric Medicine, and before that as an engineer with the US Navy. where she specialized in the design of diving equipment including rebreathers. Dr. Lance lives in Durham, NC, where she splits her time between scientific research consulting and writing non-fiction books.