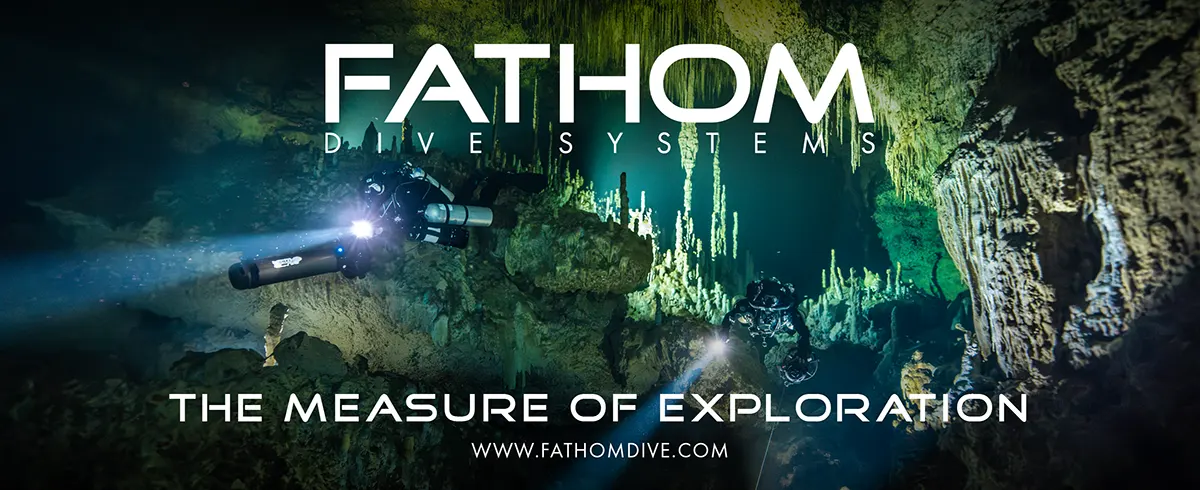

Cave

Close Calls: I Ripped My Drysuit a Kilometer Back In The Cave

It’s a potentially life-threatening equipment failure that most divers have thought but, but outside of minor leaks, few have experienced, and almost none have trained for. It certainly got the attention of photographer Fan Ping as he felt the chilly Florida spring water rush into his suit. Here’s how he survived the dive.

By Fan Ping

🎶🎶 Pre-dive Clicklist: 平凡之路 (The Ordinary Road) by Pu Shu

Finally I had to say goodbye to my six-year old drysuit, in an unexpected way.

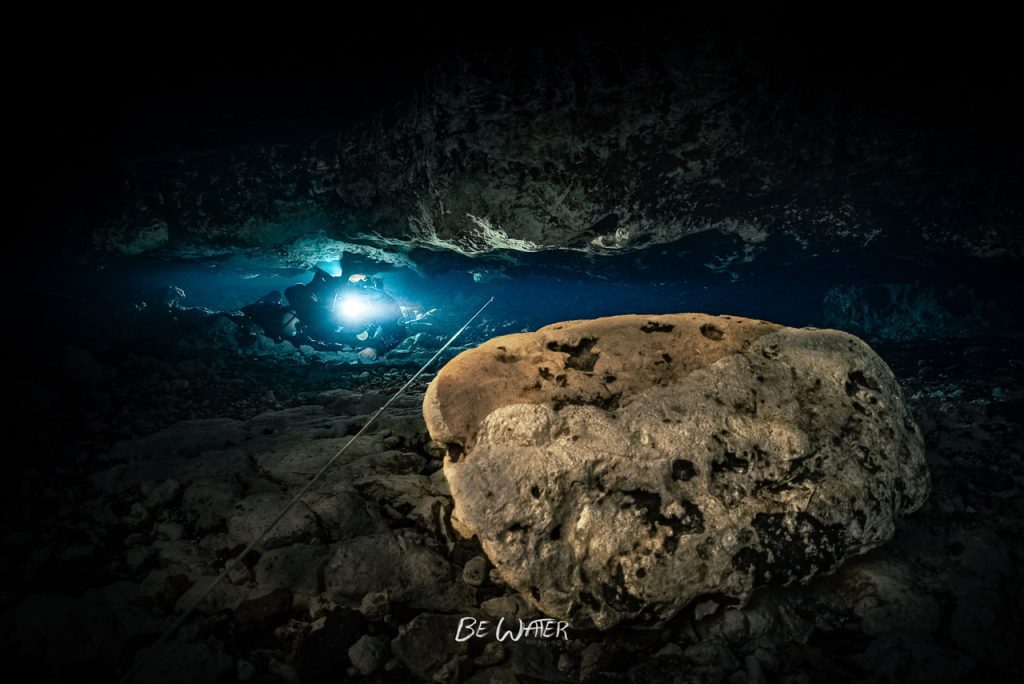

It was a cloudy day in January. There were not many people at Ginnie Springs in Florida as the temperature there was still too cold for the inflatable unicorns and flamingos with their masters in swimsuits that you see so often at the park. My friend Derek Dunlop and I met at the parking lot in front of Devil’s underwater cave system, and we started preparing for our photo shoot in Berman’s Room, at about 1006 m/3400 ft on the main line.

As usual, we had first talked about the shooting plan with a storyboard and had decided to go in with six video lights since Berman’s Room is pretty big and fairly tall. Then we started preparing our rebreathers, but things did not go smoothly. Derek had a leak in his DSV, and then one of his O2 sensors stopped working for an unknown reason. Fortunately, he managed to fix both problems, but by then it was almost 2 pm already. I am a firm believer of ‘Rule of Three’ (If you have three major problems before you start the dive, then you should quit for the day), but I am also a photographer who was eager to capture the last piece of my Ginnie Springs project.

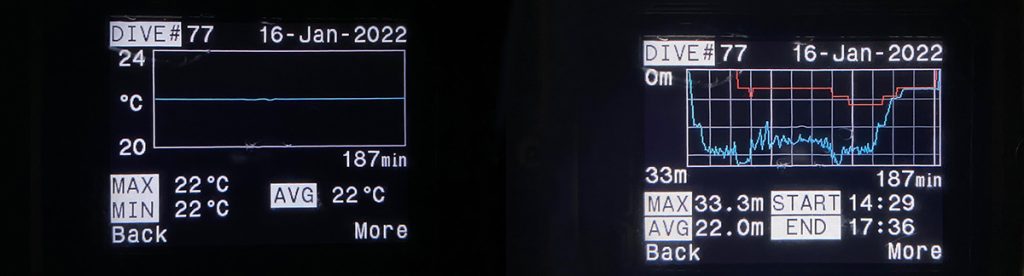

We got on our scooters and started diving. When I have many lights, I usually put two on the camera, which is side mounted on my right like a tank, two in my left thigh pocket, and the rest on my buddy. We dropped our own sidemount bailout tanks at Stage Bottle Rock at 1800’ and arrived at our destination 45 minutes into the dive as planned. We spent about 60 minutes playing with the lights and shooting, and then turned the dive happily at 105 minutes.

I was leading on the way out, riding in the high flow and thinking about the photos. When I passed the restricted tunnel before the Henkel restriction, the third problem of the day finally came. Scootering with the flow at perhaps 1 m/sec, the corner of my left pocket on my drysuit got caught on the tip of a rock and ripped a 3cm x 3cm hole. I could feel the chilly water flooding into my suit, so I stopped immediately, and within 10 seconds I lost my trim and buoyancy and was kneeling on the floor like in my Open Water class.

I told myself to “stop and think!” As in all the training we have done, I realized this was not an immediate life threatening situation, but the snowball could start rolling if I did not act correctly in a calm way. I checked my computers and used my primary light to get Derek’s attention and told him my drysuit was done for with the universal hand signal. Then I put some gas into the wing, but I was still on the floor. With more gas into the drysuit, I started moving again, in a vertical fashion.

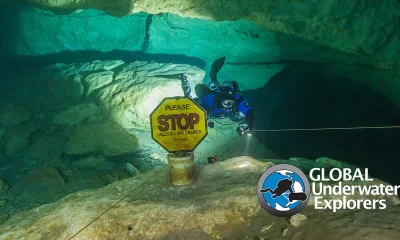

As you all can imagine, I had to put myself on the floor again at the Henkel. It is not extremely tight if you choose the right path, but with the DPV and camera and the Global Underwater Explorers (GUE)-configured JJ-CCR on my back, I was worried that I might not get out of the cave smoothly. Usually I stay very calm during a dive, but the depth was 32 m/105 ft, and the clock was ticking I was unsure of what would happen with that hole in my drysuit. I dumped all the gas in my suit and carefully crawled out of the restriction. Luckily, visibility is not a problem in Ginnie’s main tunnel because of the flow, and I can verify that a v-drill is easier when you have your belly on the ground.

To be honest, this was when I just completely got out of the panic mode. I knew I was getting closer to the surface, and I would be fine as long as I stayed focused. I inflated my suit, but as soon as I tried to stay horizontal, the gas leaked out from the hole. So, I put more gas into the loop and started being dragged by my scooter like SLAVE I in Star Wars, while still having to kick the whole time against the weight of my feet.

That was when I started to feel cold. I could not imagine what this would have been like if I had been in a freezing cold cave like Orda, where the low temperature would have already killed me. All I could do was focus on scootering and choosing the taller passage if possible, in order to avoid messing with my buoyancy. Derek retrieved my bailout tank on the way out, and we made it back to the cavern in about 145 minutes, which is almost twice the time it usually takes.

There was no one else in the cavern when we started doing our longer-than-planned deco. I inflated my suit and knelt down on the rock at 6 m/20 ft so I could at least keep my torso relatively dry. I was getting colder and colder since I was not moving at all, but thanks to the 21ºC/70ºF degree spring water, my mind was still clear enough to think about getting a rental drysuit at Extreme Exposure and coming back in two days. After about 40 minutes of deco, we got back to the surface, and I had a really hard time walking back to my truck with all the water in my suit. What is worse, even the clouds started crying for me (or perhaps for my drysuit).

A fully flooded drysuit is something we always had talked about in our training but would never practice on purpose. When it actually happens, one can lose his trim and buoyancy within seconds, resulting in much more serious problems; for example, navigation, extended deco time, and hypothermia.

In retrospect, I think there are 3 reasons why it happened to me:

- I was diving a Kirby Morgan M48 Mod-1 full face mask to facilitate better communication with my model, but the vision was relatively limited,and I did not pay enough attention to the surroundings;

- I had two big video lights in my pocket, and the pocket was exposed as I dropped my sidemount bailout tank;

- I should have gone slowly or maybe swum in more restricted areas.

I consider myself lucky that I got nothing but cold and lost nothing but an old drysuit, and thanks to Derek who made the process easier. It could have been a totally different story in another cave with a silty bottom or freezing cold water. However, out with the old, in with the new; it was time to get another drysuit.

Have you or a teammate ever had a “close call” while diving? Please take a few minutes to complete our new survey: Close Calls in Scuba Diving

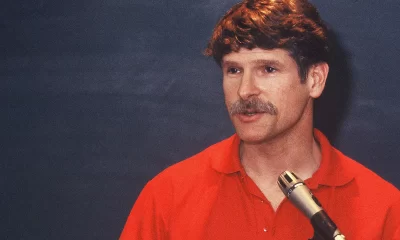

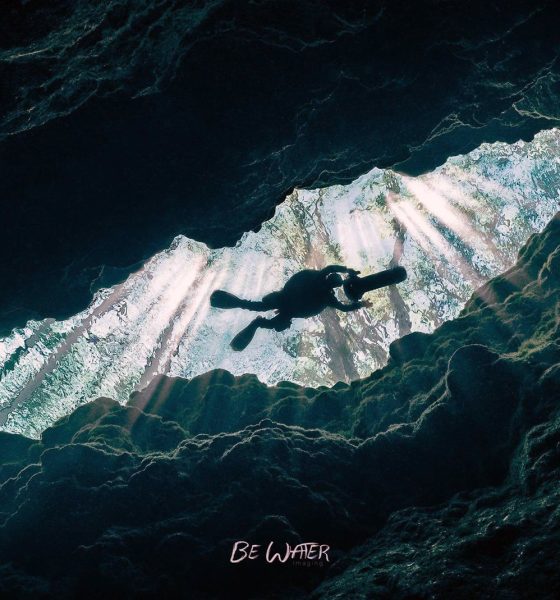

Fan Ping is a Chinese photographer and filmmaker based in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, and is dedicated to showing the beauty of the underwater world to people through his lens. He is specialized in combining artistic elements with nature and complex lighting skills in overhead environments, and this artistic style has brought him international acclaim, including awards from many major underwater photo/video competitions. You can follow his work on Facebook and Instagram: Be Water Imaging.

The best of Fan Ping’s work can be purchased at: www.bewaterimaging.com