Education

High-Pressure Problems: Pulmonary Edema in Technical Divers

If you don’t know much about immersion pulmonary edema (IPE) have a read! This not-well-understood disorder is on the rise and can not only effect tech divers, but seriously ruin your day if you’re unaware and unprepared to deal with it. DAN. Tekkie Reilly Fogarty has the deets!

By Reilly Fogarty

The ability to reduce risk to an acceptable level through careful planning and preparation is something that we as technical divers often take for granted. Whether it’s preparing for a case of decompression sickness (DCS) or developing contingency plans for equipment failures, we often focus on the potential hazard and assume we’ll be able to identify the trigger and plan our response well ahead of time.

However, occasionally a hazard comes along with risk factors that we don’t entirely understand, and treatment options that are either nonexistent or impossible outside of a hospital. Immersion pulmonary edema (IPE) is one such hazard. It affects divers across the gamut of health, experience, and environments, and it can cause serious injury or death.

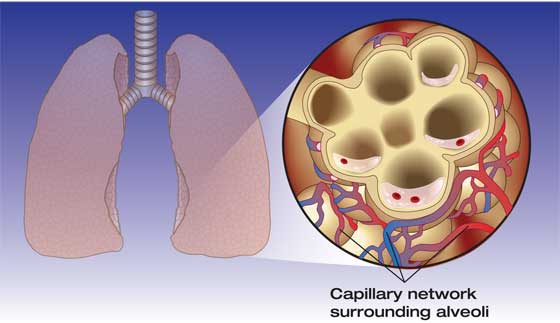

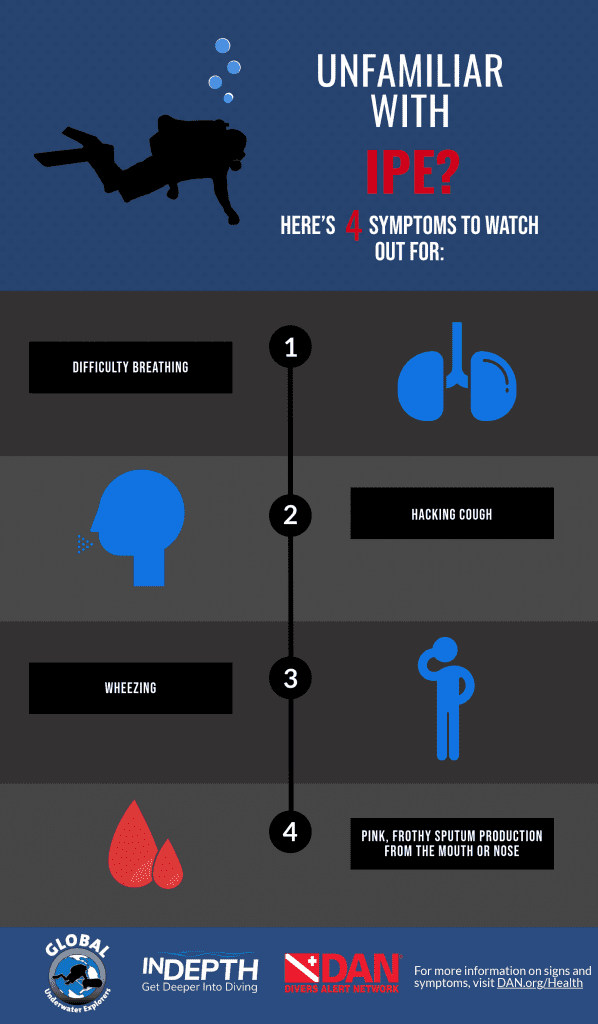

IPE is a condition in which intravascular fluid diffuses into the lungs due to an unclear mechanism with an incomplete list of triggers (more on that later). It has the ability to present an acute hazard with little warning. As the fluid enters the lungs it causes coughing and difficulty breathing, and symptoms will increase in severity as fluid buildup increases, eventually causing hypoxia and death if left untreated.

It would be easy to harp on the severity and abrupt onset of the condition for the sake of sensationalism, but the reality is that IPE is an uncommon though serious condition, and divers who recognize its onset quickly and take appropriate actions, typically recover with no residual ill effects. Fear of IPE shouldn’t keep you out of the water; as with DCS the risk can be managed, and like DCS it is a condition that you should be able to spot in yourself or your teammates as soon as symptoms appear.

Who is at Risk?

A decade ago, IPE would have been described as uncommon or nearly nonexistent. First reported in 1989, it was originally thought to be the result of cold-water diving and was called “cold-induced pulmonary edema.” In recent years, however, reports have increased significantly, and it has been seen in divers of all types. More than 300 cases have been published, and it has been reported at rates of 1.8 percent to 60 percent in two- to four-kilometer open-sea swimming trials among military recruits. Between one and two percent of triathletes have also reported symptoms consistent with IPE in some studies.

The condition was recognized as a serious concern when it appeared in otherwise healthy Navy SEALs who had undergone rigorous testing and were in excellent shape. Several of these SEALs developed IPE while swimming in San Diego Bay during training, and the Navy turned to the Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Environmental Physiology at Duke University Medical Center to research risk factors and treatments.

The study was particularly interesting because the patients had “no obvious preconditions to IPE, such as high blood pressure or cardiac defects,” the center’s medical director Richard Moon, M.D., said. Moon’s research has indicated that high blood pressure and cardiac defects likely increase an individual’s risk of IPE, but the condition could potentially affect a large demographic of the diving population who don’t have any obvious medical concerns. His current research involves using echocardiography on submerged subjects to investigate a possible correlation between increased pulmonary artery pressure and IPE susceptibility. One theory is that individuals who are susceptible to IPE may have slightly less flexible left ventricles, which may result in increased cardiac filling pressures. That study is ongoing, however, and results have yet to be published.

What causes IPE?

The current working theory is that IPE is a result of a hemodynamic imbalance between the lungs and the surrounding tissues. Much like our understanding of DCS, our understanding of IPE relies on correlation (rather than causation) and several well-researched but unconfirmed theories. Tissue pressures in the pulmonary system rely on a group of factors collectively known as “Starling Forces,” which include oncotic pressure in the capillaries and interstitial fluid, permeability of capillaries, hydrostatic and hydraulic pressure in the capillaries and interstitial fluid, and alveolar pressure. When the balance of these Starling Forces is skewed with high blood pressure, increased work of breathing, large volumes of fluid shunting to the core due to immersion in cold water, overhydration, and/or other factors, this may cause fluid to diffuse into the lungs. This can result in the symptoms discussed above, including coughing and difficulty breathing, which eventually could lead to hypoxia and death if not treated.

Divers who suffer from IPE should be removed from the water immediately, given oxygen, and brought to emergency care. Once the primary trigger for the condition (cold water, work of breathing, overhydration, etc.) is removed from the equation, most individuals experience a relatively quick improvement and eventual resolution of symptoms. However, some may require hospitalization and the use of diuretic medications to reduce excess intravascular fluid. Because of the possibility for “dry drowning” and medical complications, it’s important that divers who experience IPE be evaluated by a healthcare professional, but most divers who are able to rapidly exit the water and begin surface oxygen experience no long-term effects from the condition.

Aside from evacuation from the water and medical interventions to remove the fluid from the lungs, there is currently no treatment for IPE. In this lies the crux of the issue for technical divers, who may be restricted from surfacing for hours after symptom onset, as in the case of a rebreather diver last year. In situations like these, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and divers will have to balance the risk of DCS with the severity of IPE symptoms in real time.

Some research has shown that the drug sildenafil (commonly known as Viagra) may be able to ameliorate IPE risk in athletes, but research is limited and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis by a qualified physician. Adequate (but not excessive) hydration, cardiovascular fitness, including management of blood pressure, lowered work of breathing, and decreased thermal stress are excellent broad strokes to reduce your risk of IPE. However, if you have experienced the condition before, or think you may be particularly susceptible, it’s a good idea to have an honest discussion with your favorite dive-medicine-trained physician.

Dive Deeper:

Extreme Exposure: Research by Richard Moon

Diagnosis of swimming-induced pulmonary edema – a review

Sildenafil: Possible Prophylaxis Against Swimming-Induced Pulmonary Edema (SIPE)

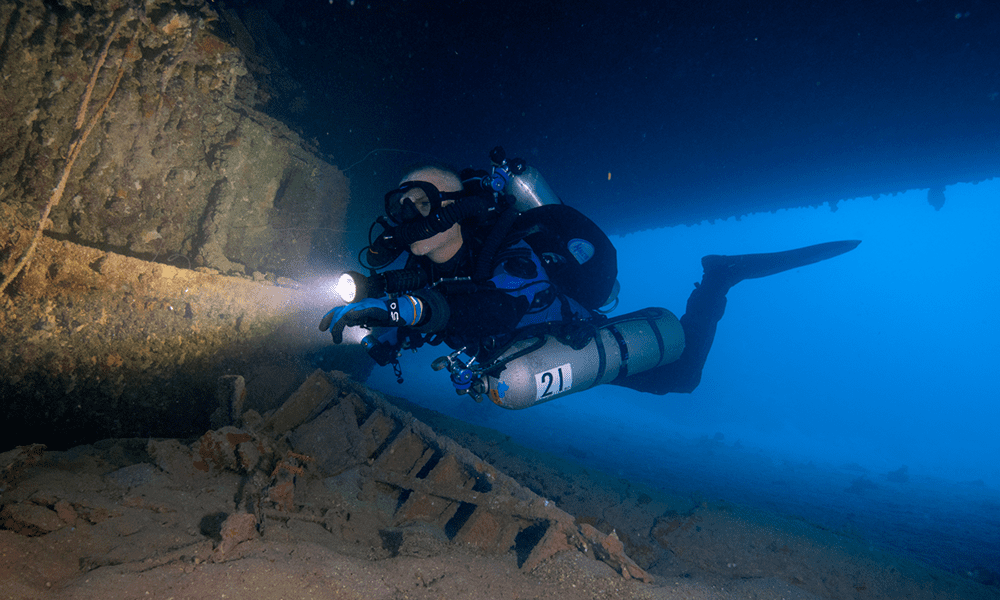

Header photo by Jesper Kjøller.

Reilly Fogarty is media strategist at Divers Alert Network (DAN) and team leader for its risk mitigation initiatives. He is a USCG licensed captain and rebreather instructor whose professional background includes surgical and wilderness emergency medicine, and dive shop management.