Latest Features

GUE Project Diving from Foundational to Exploration-grade

By Jenn Thomson. Photos by Sean Romanowski, SJ Alice Bennett, Bori Bennett, Jesper Kjøller, Lauren Wilson & Erik Wurz.

Reprinted from QUEST Vol. 25 No. 3—August 2024

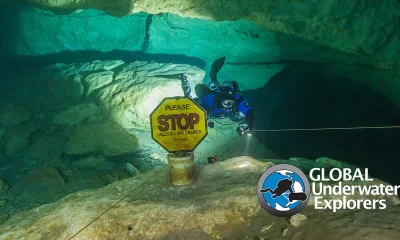

From the original exploration of the Woodville Karst Plain Project (WKPP) to the local teams around the world that dive with a purpose, project diving has always been an integral component of GUE’s philosophy. However, project diving is complex, requiring both hard and soft skills as well as a plethora of experiences to reach exploration-grade levels in globally relevant projects. This is the challenge that aspiring divers face. To address that challenge, GUE is introducing several initiatives—from resource development to a new training curriculum—in order to provide support for the next generation of project divers.

GUE’s philosophy comprises a holistic approach to scuba diving while promoting a quest for self-improvement, intellectual curiosity, and life-affirming experiences. Most importantly, GUE divers are both highly skilled and motivated to undertake goal-oriented and purposeful diving, helping to facilitate the broad range of conservation and exploration objectives the agency promotes. Indeed, GUE began with a team of explorers who shared the vision to enhance project diving around the world and elevated the quality of instruction at all levels. Now, the next steps are to combine these two branches. This article summarizes several GUE resource and training initiatives in active development for project divers.

GUE Project Definition

While not officially GUE Standards per se, the first iteration of the Project Diving Definition v1.0 aims to standardize the main features of a GUE Project, such as its types, taxonomy, values, and benefits, while allowing for flexibility and contingency.

A GUE Project is defined as a goal-oriented scientific, educational, explorational, and/or conservational endeavor. Projects require a team of divers and support personnel who use advanced planning techniques, unique diving skills, and appropriate technology to realize their objectives.

Project goals should be measurable, specific, and defined within these categories:

- Exploration (e.g., scouting, searching, prospecting)

- Documentation (e.g., photo/video, survey, photogrammetry)

- Sample collection (e.g., data and/or specimens for scientific research)

- Conservation (e.g., beach cleanup, ghost net removals, planting sea grass)

All GUE Projects must also meet several administrative requirements, for example:

- Project Managers are leaders of missions and are registered with GUE Headquarters prior to being promoted.

- Participants sign appropriate liability releases and are governed by appropriate Risk Management and Crisis Response Plans

- Projects are designed to ultimately bring value to GUE’s organizational initiatives.

There are also taxonomic recommendations. GUE Projects can be recreational or technical, or a combination of the two. Recreational GUE Projects are depth limited to 30 m/100 ft in backmount open-circuit and must be conducted in open water within minimum decompression limits. Project Managers must be GUE-certified for the level of planned project diving, at minimum. Recreational project participants are not limited to GUE standard equipment configurations or certifications but must adhere to GUE General Diving Standards. Technical and Cave GUE Projects are more complex in nature and involve deep water, overhead environments, specialized equipment, and/or extended decompression obligations. Ninety percent of the divers need to be GUE-certified at an appropriate level and use GUE standard gases and equipment configurations, unless the Project Manager decides otherwise—within reason—or if the environment, goals, or circumstances necessitate variations. To this end, projects maintain a balance between adhering to GUE standards while catering to unique contexts of real-world projects.

The Project Portal

So, you want to set up a project yourself but have no idea where to begin. Or, you are a seasoned project manager but you’d be a lot more comfortable with additional support for social media outreach or templates of risk assessment forms, for example. The newly developed Project Portal is intended to help both dive participants and project managers and is part of GUE’s DREAM initiative that will help divers to clearly:

- Define their project’s objective(s)

- Research properties that illuminate that objective

- Explore their environment and record observations

- Analyze and assemble observations in an accessible manner

- Motivate individuals in support of the underwater environment

The portal itself is a standardized set of planning tools that form the twelve stepping stones of a successful project. Each of these twelve steps forms its own veritable library of resources from which divers can pick and choose to aid in their own project development. The intended result is the inception of a broad range of individual projects that are context-specific while still guided by standards of excellence in conservation, education, and exploration. So, what are these steps?

FACTFILE // The 12-steps for a successful Project (Project Portal):

- Defining/Overview/Goals

- Plans/Permits/Budgeting

- Registration

- Team Recruitment

- Medical and Liability Admin

- Health/SOPs

- Logistics/Travel

- Project Timelines

- Diving Plans/Gear

- Data Management

- Media/Outreach

- Reports/Delivery

First steps

An overview (1) sets the scene for each project: information that will inform the project goals (specific measurables of success), taxonomy (the type of recreational or technical GUE project), and its values (the “why”). Clear definitions upon inception will, in turn, help project managers decide on the resources, team members, and deliverables needed—avoiding a drift in the overall mission’s focus. Planning (2) is the next important step, whether one decides to use a Gantt chart to document a general timeline of all phases (e.g., planning, project, debrief), or already has defined project weeks with specific recruitment days. Of course, economic factors come into play: Do you have grant money already? Do you need to apply for funding to procure specialized scientific or filming equipment? Do you need to require participants to pay a fee for logistics, gear rental, and accommodation? And, of course, there is the sometimes not so small issue of gaining the appropriate permissions. This could mean scientific permits for biological or archaeological research, landowner permission if on private property, or filming permits in culturally important or environmentally fragile sites.

Registered projects

GUE Projects that are registered (3) with HQ will benefit from having the mission publicly available on the GUE website so team recruitment (4) can begin. This is surprisingly complex. For starters, numbers. How big are the objectives, and how many divers will the project need to achieve reasonable success on a single dive? Will a single team complete multiple dives, or will multiple teams alternate in single dives to divide labor and capacity? How many individuals can fit on a boat? Then there are the skill sets to fill—both hard and soft skills. Are there enough divers who have medical, photogrammetry, or filming experience? Yes, there needs to be a minimum certification level, but can others participate to help as safety divers, conduct data analysis, and help topside? And possibly most importantly of all are the soft skills—teams must be able to effectively carry out contingency and emergency situations, have good cohesion, and willingly act as ambassadors for the underwater world.

More planning

To be prepared for emergency situations, teams should file the appropriate paperwork, especially related to medical and liability matters (5) for legal protection and emergency contacts. If necessary, a diving safety officer might be required for some projects. In addition, GUE Projects must follow or use:

- Standard Operating Procedures (6)

- Forms, including crisis response and risk management plans

- Emergency equipment and procedures that match the level of project remoteness

Next is making arrangements for logistics and travel (7). Again, there are a lot of moving parts here. Are participants making their own way there, or is the entire group catching a plane or boat to the site? Is the accommodation a hotel that can cater to all dietary preferences, or is it a remote camp in a jungle that necessitates self-sufficiency and save-a-dive kits? How will one transport specialty goods such as lithium batteries and oxygen? What about drying rooms for undersuits, on-site compressors, tank availability, and the ability (or not) to pop around to a local hardware store?

Execution

A weekly project timeline (8) can include preliminary briefings, dry runs, dive site scouting, data collection, processing, wrap up, and evaluation/analysis if necessary. In essence, a project timeline should provide a clear overview of the goals for each day, potentially keeping a few spare days flexible for contingencies due to bad weather, conditions or other reasons. Communication is essential for team awareness regarding project progress. To aid this, the team could.:

- Host online information meetings before the project on day 0 to acquaint all participants with the site

- Complete a shakedown on day 1 to assign responsibilities

- Debrief after any major changes, milestones, or objective completion.

Additionally, let’s not forget each individual dive plan (9) with associated activities and gear required (9). Are there any specifics or project variations that need to be included alongside the standard GUE EDGE pre-dive process for dive planning? What are the steps that need to be followed regarding scientific protocols, both in terms of data collection underwater and special equipment preparation beforehand? What are the surface support roles on that day? Who is driving the boat, who are the on-deck support members for the divers, and/or who is receiving the artifacts topside? Are there any changes that need to occur based on the previous dive?

Pics or it didn’t happen

Finally, you can have the best project in the world, but what happens if nobody knows about it? A good social media plan (11) and reporting/deliverables (12) at the end of the project support outreach goals and help future project iterations gain traction. Social media best practice requires publication permissions—especially with scientific data collection content. Photogrammetry models often need to be released with a watermark and the creator’s name. Any volunteers or collaborations can also be mentioned in the acknowledgements of academic papers, along with any data analysis conducted for transparency. This is why it is so important to have a good data management system (10) throughout as well as after the project. Memory cards, photos, and wetnotes data must be included in an inventory or file system and backed up daily (or as soon as possible). One can then see any gaps or lost samples. Data management systems also save time writing reports.

For a good example of these steps and project-specific considerations in action, see “Cave Exploration 101” in Volume 25.1 of Quest, GUE’s quarterly magazine.

Project Diver Curriculum

And then we come to those that seek more formal training, or training, in a safe manner at a high level for the exploration-grade projects. This is where the Project Diver curriculum comes into play. By developing a new, formalized training pathway that will bring together the experiences of project diving with the rigors of a GUE course, the organization will elevate community dive teams to new heights.

From its past inception to its current development phase, the GUE Project Diver curriculum has always had a high-level goal in mind: to help facilitate programs that explore and preserve the global aquatic environment. Such goal-orientated diving can be as simple as a shallow-water conservation project or as sophisticated as a large-scale photogrammetry mission with integrated GIS data collection systems, or exploratory work that combines archaeological preservation with remote logistics.

Considering both mandatory knowledge and project-specific requirements, the Project Diver Curriculum will include specific Core Modules and Apprentice Projects designed for individual skill levels and chosen environments (e.g., cave, technical, or ocean dives). In the Core Module, aspiring divers will explore their own tailor-made curricula for project needs; this will cover theory and dive workshops, complex project organizational skills, credible scientific data collection, and report/deliverable production. After successful completion, divers will put the theory and skills into real-world contexts during Apprentice Projects, where they will complete an entire project from start to finish.

Core Module

The content of a Core Module is diverse; a selection of topics is below:

Project management and planning. These lectures focus on the steps to a successful project, including factors such as team selection, funding, managing large amounts of data, liability and risk management, and scientific report writing. There is a large overlap between the topics here, and the steps are similar to GUE’s Project Portal resources.

Photogrammetry. This is a technique that uses 2D photographs to measure and map objects and environments. Upon taking multiple overlapping photographs, specialized software can identify common points between the images and calculate their positions in 3D space. The use of unique markers or natural features in photogrammetry can result in geo-rectified models. If these markers have known locations (measured using GPS or other methods) within the area being photographed, the model can be aligned with real-world geographical coordinates to create accurate GIS maps and visualizations. This technique is particularly useful for documenting shipwrecks, coral reefs, or archaeological sites.

Underwater archaeology. Sometimes delicate archaeological remains need to be lifted from the water rather than being photographed and left in place. The Core Module covers specific techniques for removing such fragile artefacts. Divers can practice removing human skeletal structures by packing and transporting them in a mix of plastic containers, crates, cushions, and flotation devices. Such simulations are supported by lectures with real-world examples, such as the notable collection of “Naia,” one of the earliest American human skeletons at ~13,000 years old in Mexico’s Hoyo Negro cave. GUE divers played a role in the discovery, collection, and documentation of that skeleton.

Decompression habitats. Habitats are gas-filled underwater spaces that allow divers to remain at pressure and often make decompression more enjoyable if the deco time is several hours at depth in cold environments. Careful setup of habitats is required to ensure stability, balance, and safety within the enclosure, especially if the habitats are custom-made (upturned rigid bathtubs and inflatable smaller tarpaulins come to mind). In the Core Module, divers can practice bringing in the habitat, maximizing the air space with gas fills, and making sure that the system will not tip over or collapse (by either securing it to a “ceiling” akin to a cave system, or anchoring it using ropes and attachment points).

In-water recompression. Divers suffering from decompression sickness (DCS) in remote areas can benefit from in-water recompression (IWR) in certain contexts and situations. This technique involves bringing the diver back down to depth to reduce bubble formation/symptoms. Albeit controversial with safety concerns and additional planning required, it is recommended that, in order to reduce drowning risk during IWR, a full-face mask be worn in order to communicate with the victim and to check responsiveness. Hence, the Core Module simulates dedicated complex rescue scenarios as well as full-face mask skills.

Remote operations. Workshops can include the field maintenance of gear, such as drysuits, rebreathers, DPVs, and regulators.

Medicine. Using the latest resources and research from DAN (Divers Alert Network), the Core Module can include modules and sessions on different physiological and medical topics. For example, topics can include first aid and the Diver Medical Technician course, the link between heart rate variability and DCS, and real-time physiological diver monitoring. The latter refers to the DAN-SMART Program (Sports Monitoring and Advanced Remote Telemedicine) that has developed wearable technology for real-time monitoring/recording of physiological signals and vital signs. So, for example, expedition divers can use these tools to continuously measure their body position, blood oxygen saturation, breath rate, and body temperature. Depending on the changes in the diver’s physiological status, medical personnel can either advise the divers to change the plan or send out support teams in an emergency.

Next steps

Several Core Modules have been run in six-day pilot tests to explore these different topics (Deep Dive Dubai, May 2022 and High Springs, October 2022). The next step is to curate online content so that a growing part of the Core Module can be a remote learning experience designed to prepare participants for practice in their specific Apprentice Project. While there will be standard modules for everyone to participate in (e.g., project management and rescue scenarios), unique elements will be taught at different levels (e.g., augmented academics and in-water skills) for those with cave and technical requirements. These topics are in active development within the agency. Teaching project diving to the next generation of aspiring scientists—at both the foundational and exploration levels—is of primary importance to GUE.

This is why we are actively crafting the Project Diving curriculum standards to include recreational variations and other roles, in addition to technical and cave iterations. We hope to soon offer a full set of resources for all levels of GUE project diving.

DIVE DEEPER

GUE: GUE PROJECT PORTAL

InDEPTH: Let’s Get to the Core: GUE’s New Project Diver by Francesco Cameli

InDEPTH: Building A Strong Community Through Project Diving by Amanda White

InDEPTH: Decompression Habitats Are Ascendent by Andy Pitkin

InDEPTH: How I Became a Scientific Diver by Jenn Thomson

Jenn Thomson

Jenn was GUE’s 2022-2023 NextGen Scholar, showcasing recreational scuba’s role in scientific operations. She highlighted NASA astronaut training, Middle East ecosystem surveys, and global GUE events to inspire young divers. Jenn completed Drysuit and Doubles Primers, the Scientific Diver and Rec 2 course, and an ITC. She aims to connect space and marine sectors via scuba diving and exploration. In January 2024, Jenn joined GUE HQ part-time as Global Project Coordinator, Project Baseline manager, and facilitator of NextGen Scholarship Legacy Projects. She is developing the Project Portal and Project Diver curriculum.

Instagram: @jennelizabeththomson