Latest Features

From Fear to Fieldwork: How Science Rewrites the Shark Story

In a rare meeting of science and lived experience, Cristina Zenato, Dr. Sara Andreotti, and Dr. Yannis Papastamatiou discuss fear, data, and how divers can turn fascination into protection — without the drama.

THE TALKS – A Round Table Rhetoric with Stratis Kas.

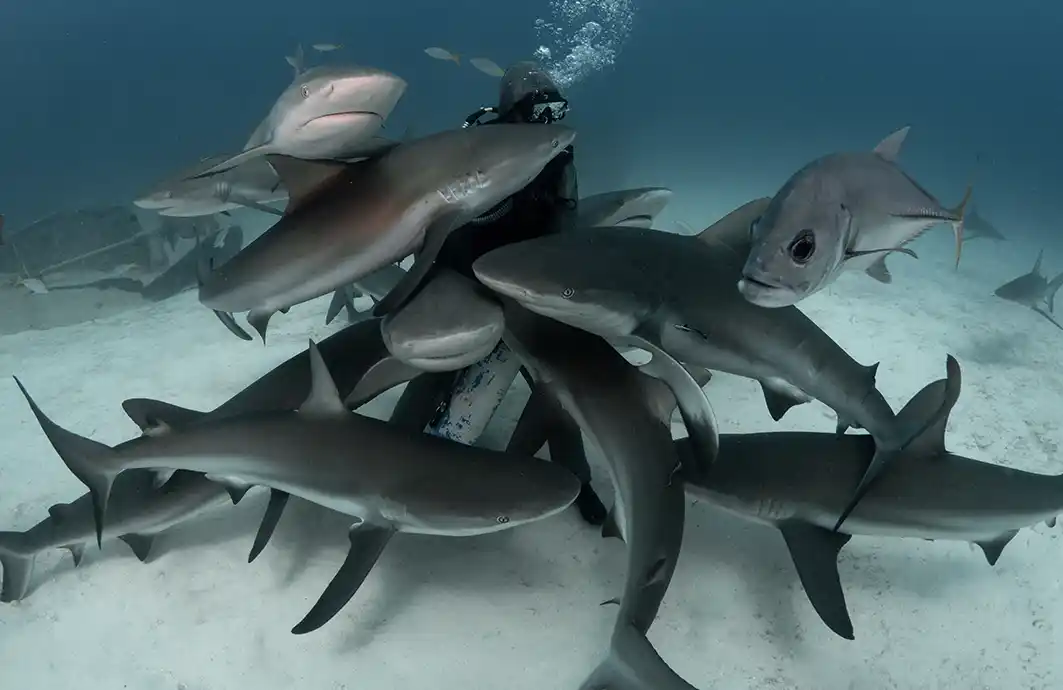

Lead Image: Cristina surrounded by a local shiver of Caribbean reef sharks she works with. Photo by Kewin Lorenzen

Shark behaviourist, cave and ocean explorer, environmental conservationist

Marine Biologist, Shark Geneticist, Lecturer, and Conservation Entrepreneur

Marine Ecologist, Shark Biologist, Author, and Educator

Sharks aren’t headlines; they’re data. In this round table, Bahamas-based shark behaviorist and cave pioneer Cristina Zenato joins marine biologist Dr. Sara Andreotti,and behavioral ecologist Dr. Yannis Papastamatiou to swap viral clips for evidence: dorsal-fin photo-ID that separates sightings from individuals, tagging that shows migrations don’t bow to bait, and field protocols that turn ecotourism into education instead of spectacle.

For technical divers, the nuance matters: Rebreathers can alter approach behavior, bubble noise shapes proximity, and site seasonality trumps any itinerary. Come for the adrenaline, stay for the dismantling of myths: “Seeing isn’t counting,” “More sharks by the boat” ≠ population boom, and a baited pass ≠ a natural hunt. If you plan blue-water ascents, ride currents, run staged decompression, and carry redundant signaling, bring the same rigor to shark claims—methods over mythology.

Kas: Before we dive into the evidence, a warm welcome to our guests: Cristina Zenato, Dr. Sara Andreotti, and Dr. Yannis Papastamatiou. Let me dive right in, and say that for divers—especially those of us running mixes, managing deco, and planning blue-water ascents—sharks aren’t a side note; they’re part of how oceans stay functional. We may like them, or not. What’s certain is that we need them.

However, for some of us (me included), they’re also the reason we sometimes choose a different entry point—because of an irrational fear—one thatI hope you will set aside by the end of this talk. Thank you all for being here and for helping us replace lore with literacy.

Sharks are among the oldest species on Earth—millions of years of evolutionary success—yet our perception is still framed by fear more than biology. We rarely admire their resilience and adaptability. You three work with sharks—and appreciate them. Tell us about your first close shark encounter: did it shape your view?

Cristina: My first underwater encounter with a shark was on my very first open-water checkout dive in the Bahamas. As soon as I jumped in, there were a dozen Caribbean reef sharks. That dive shaped the rest of my life. I surfaced, and within a week I left everything—my career, my boyfriend, my apartment—and moved to the Bahamas so I could keep diving with sharks. My perception of sharks was already positive; as a child I dreamed of having sharks as friends. So that first encounter changed my life, but not my belief—I already believed in them.

Sara: The first time I saw a shark while diving was in South Africa. I went shark-cage diving, like many tourists, expecting to see a great white right in front of me. I didn’t expect it to be so different from what you see on TV. Before getting in, looking at this really big animal, my first thought was, “Oh my goodness, what am I doing?” But as soon as I hit the water and saw it underwater, that shifted to, “Wow, you’re so cool.” They eventually took me back on the boat because I was hypothermic—I would have stayed there all day. That experience also changed my life.

Yannis: The first shark I ever saw was on my first dive in the U.K.—a catshark, one of the smallest sharks I’ve seen. I was ecstatic; I’d been wanting to see a shark for 19 years. It didn’t change my view, because by then I was already doing my undergraduate in marine biology and committed to studying sharks. I grew up learning to dive in Greece—there aren’t many sharks there—so I’d never seen one and was desperate to. I didn’t expect my first shark to be in U.K. waters, not a place you imagine seeing too many, but there it was: a little catshark.

Kas: Could you talk about what role the diving community plays in shaping public views—good and bad?

Cristina: That’s a whole podcast on its own. The diving community can—and does—shape a very positive outlook on sharks and shark encounters. These days everyone has a camera—GoPros, phones—so people surface with images of their encounters. Like you said: “I was swimming along, a shark came by, and it just kept going.” That normalizes sharks in a good way. There’s a negative side, too. In a world of 15–20 second clips, there’s a tendency to post the “spicy” moment—or to frame it with dramatic wording.

On the positive side, I really believe regulated shark dives and tourism—done with the safety of participants and sharks in mind—are beneficial. Where it becomes damaging is when divers use sharks as props: not out of love for the animals or to share something meaningful, but to ask, “What can this shark do for my likes?” I see that trend on social media—sharks reduced to accessories—which can push people into actions that reinforce negative images.

As with anything, it varies by individual and operator. There are great instructors and operators doing good work for sharks, and there are bad ones doing harm. We should also counter misrepresentation on social platforms.

Yannis: I agree with Cristina. From a scientific standpoint, ecotourism around sharks is controversial—in science and in public opinion. I’m actually pro-ecotourism for its advantages, if it’s done well—and that “if” matters. There are excellent operators who prioritize human and shark safety and include real education. There are also plenty who don’t; you don’t have to look far on social media to find bad examples. But scientifically, I support ecotourism when it’s well executed.

Kas: Sara, since you work on great whites and population genetics … from a population-level perspective, under what conditions can shark diving genuinely benefit sharks and their ecosystems?

Sara: I work with white sharks and moved to South Africa in 2009. I echo what Cristina and Yannis said: when done correctly, shark ecotourism is an incredible tool because it brings people face-to-face with sharks, and sharks are their own best advocates. It also creates a financially sustainable platform to observe and collect data. Our research is expensive—you need a boat, chum, a skipper, and the knowledge of where to go. Grants are often structured for land-based work, which makes things challenging. Ecotourism lets scientists observe without carrying all the logistics.

In South Africa, regulation has been key: from the start, operators’ permits enforced a precautionary approach—no feeding, use bait items that are part of sharks’ natural diet, and give tourists clear information about population status so the message is accurate. Not everyone is the same—some push the adrenaline angle—but overall it’s been successful. White sharks became financially valuable alive, and coastal communities benefited—hotels, restaurants, transport, souvenirs. The impact is massive, and it helped conservation: South Africa protected white sharks in 1991.

KAS: It’s sad that animals survive because it’s good for business, rather than because they have the right to exist.

Sara: It is sad, but that’s often how the world works. We’re trying to persuade governments and people that caring for the environment is the smart choice—financially, too. In the long run, a healthy ecosystem beats constant crisis management. But while we work toward that mindset, we need ways to protect animals beyond a purely moral argument.

Cristina: I’d add that “financial benefit” often comes with an education benefit. In the Bahamas, thanks to shark tourism, I trained dozens—maybe hundreds—of Bahamians to scuba dive; many became shark-tourism operators. The push to protect sharks there came from Bahamians themselves: they went to the government and asked for protection. Yes, there’s financial incentive, and yes, some operators aren’t perfect, but that unified local voice led to the Bahamas becoming a shark sanctuary in 2011. So economics can lead to education, which leads to political action—one of the most powerful tools we have.

KAS: Many divers—including me—see sharks as unpredictable, but your research often shows clear patterns. From a behavioral-ecology perspective, how do diving practices—close approaches or repeat interactions—influence sharks’ natural behavior?

Yannis: This is largely a good-diving-practices question: how should divers behave around sharks for their own safety and for the animal’s welfare? Cristina has more hands-on shark-diving experience, but from the shark’s side, most diver–shark interactions involve calm animals and are enjoyable for everyone. That’s the norm. The downside is that it can give divers an incomplete impression. Very few people see sharks truly foraging, which is different from baiting a shark in. A baited shark isn’t necessarily in the same behavioral state as a naturally hunting shark, and that can mask what these animals are capable of.

There are warning signs when an animal is agitated or threatened. Like with any large animal, you need to read body language. Many negative incidents come down to poor diver responses—bad buoyancy, flailing arms, turning your back on a large shark, basically not respecting the animal. You can find plenty of examples online. Sharks respond to human behavior, and species matter: reef sharks and white sharks have very different ecologies and therefore different behavioral responses.

KAS: Can our interactions disrupt their travel routines or shift where they go?

Yannis: One reason I studied ecotourism effects was the claim that provisioning stops migrations—that sharks quit migrating because there’s food year-round. I’ve never seen evidence for that. Migratory species keep migrating; a bit of food isn’t enough to change those large-scale patterns.

On smaller scales, divers can have effects, depending on the area. For instance, with rebreathers you sometimes see different responses than with open-circuit bubbles. In some places, open-circuit can keep sharks at a distance; elsewhere, rebreathers make divers seem more like large, silent animals and change how sharks react. So yes, you can see small-scale differences, but at large temporal scales—like migration—I haven’t seen evidence of change due to diving.

Cristina: We see that clearly in the Bahamas. We have seasonal, organized shark dives. People show up in August asking for tiger sharks at Tiger Beach on Grand Bahama, and we tell them: you won’t. The tiger sharks are migratory—November to April. Great hammerheads around Bimini? December through March. It doesn’t matter how many operators or trips you run; if you come in August, you won’t see those migratory sharks.

On rebreathers versus bubbles: it’s species-dependent. Silky sharks, for example, can react intensely to a silent entry without bubbles, as if defending territory, whereas bubbles can signal, “You’re not something I need to confront.” Our Caribbean reef sharks are so used to bubbles that when I first took down divers on rebreathers, the sharks wouldn’t approach—very skittish. Add bubbles, and they happily come closer. So diver gear and species both matter.

Yannis: Habituation also varies by place. In Hawaii, diver surveys around O‘ahu often report almost no sharks, yet when we set lines to catch and tag, we caught plenty. Sharks there can be hesitant around divers. In the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands—uninhabited and a wildlife refuge—it’s the opposite: sharks rarely see people and are attracted to divers, approaching immediately. Diver surveys there likely overestimate abundance because divers act as attractants. Same species, different locations: in one place divers repel, in another they attract—so the numbers can be skewed by local shark behavior.

Sara: Hard to add much—what I know about chumming and shark behavior comes from Yannis’s work, and my observational experience echoes Cristina’s. For white sharks, even within the same bay, season and anchoring spot matter. When we had higher numbers, they’d be by the island in winter, offshore then moving inshore in summer—except in one area with an inshore seal colony. Operators had to adapt to natural behavior to see sharks. On the “wrong” day, they’d ignore our chum to hunt. We tried to mimic a scavenging situation with dead bait, but if conditions favored seal hunting, they’d skip us and breach after seals instead. That’s what I can add for the species I know.

Kas: Among divers, misconceptions persist. For example, people often think white shark numbers are stable because the encounters are so memorable. But sometimes the data—including yours—say otherwise. From a scientist’s perspective, what’s the biggest myth you encounter about shark populations, and how would you correct the record today?

Sara: It’s simple: seeing sharks is not the same as counting sharks. A lot of population “estimates” come from sightings, which depend on how many people are looking, how many phones are out, how many Instagram accounts are posting. If you see the same shark three times, you’ll count three sharks—unless you identify individuals.

When you ID sharks one by one, you recognize returning individuals and avoid double counting. That’s where perception and reality diverge. In South Africa, we had a fairly healthy white shark population up to the 1990s. From the 2000s onward, we saw a decline—based on photo-ID and observations. But as long as sharks showed up around boats, people assumed everything was fine.

When our dorsal-fin photo-ID database reached 400 identified sharks from over 5,000 photos, we stopped seeing new individuals. It was the same animals returning, again and again. That was a major red flag we raised more than 10 years ago, but it still wasn’t enough to trigger stronger protections because people were “still seeing sharks.” The public message should be: just because you see sharks doesn’t mean the population is healthy—and we can’t wait until we don’t see them anymore to act.

Yannis: In Florida, the myth I hear most is that shark populations are “exploding,” as in increasing very rapidly. This often comes up around depredation—when sharks take fish off anglers’ lines—which causes economic losses and a lot of frustration. Fishers report more depredation and more sharks near the boat. Those observations may be true, but it’s not biologically plausible for shark populations to explode. Sharks grow slowly and mature late; they simply can’t increase at that kind of pace. You can get changes in behavior. Sharks may learn where fishing boats are, become conditioned, and respond more. So you might perceive a bigger shark population because there are more sharks around your boat, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the overall population is larger.

On the U.S. East Coast there probably is some evidence of increases—which we’d expect. The U.S. has relatively well-regulated fisheries with measures in place for decades, so we’d expect to see some recovery. And I think we do have evidence of that. But that’s very different from saying populations have “exploded.” People are mixing up behavior with population status—and they’re not the same thing.

Cristina: Yannis, thank you for saying that—can we put it in bold? I have a question. Fishers often say “there are too many sharks; they’re taking our catch—conch, lobster.” When we see what you call an increase, is it actually an increase, or are sharks just creeping back toward original numbers after heavy human predation? We don’t really have a global baseline for what a healthy shark population looked like before we started saying, “Oh wow, they’re disappearing.”

Yannis: Great question. One of my PhD students—she’s defending in a few weeks—looked at relative changes in shark abundance in the Bahamas since sanctuary status because of claims that populations “exploded” and led to more attacks. I won’t spoil her results, but there isn’t much evidence of a big increase even after sanctuary designation. You likely had relatively decent populations already, due to factors predating the sanctuary.

For Florida, that’s a different case. When I say there’s evidence of an increase, I mean it’s trending up—which is good—but that doesn’t mean it’s healthy or back to pre-overfishing levels. Upward trajectory doesn’t equal “mission accomplished.” And establishing a baseline is hard: scientific study of shark populations ramped up after industrial fishing had already begun. We have methods to estimate historical baselines, but it’s not easy to say definitively what “healthy” was.

Sara: I’d add something on shifting baseline syndrome. One thing we do know: fish populations aren’t as healthy as they used to be. Sharks are predators, and fishers are predators. Think of Kruger National Park in South Africa during drought—there’s one waterhole and all the lions gather there. That doesn’t mean there are more lions.

Similarly, with fewer fish, you’re more likely to find both fishers and predators concentrated in the same spots, instead of spread out as they were when resources were abundant. We can’t fully prove it without robust pre-1960s/70s data, but it could explain why fishers often perceive “more sharks.”

Kas: I want to talk about the ethics of baiting and provisioning. It’s one of the strongest debates in the diving world. You’ve studied how predators respond to food cues and environmental changes. From your research, how do these practices affect sharks in the long run? And what best practices should we encourage and highlight?

Yannis: I’ll start by saying that yes, there can be ethical concerns around baiting. But if it’s done properly, the benefits of shark ecotourism far outweigh those concerns. Over the long term, we see very little evidence that baiting causes large-scale behavioral changes. Short-term conditioning? Yes—likely. But remember how these operations are set up: you don’t create a shark aggregation by opening an ecotourism site. It’s the opposite—you put your operation where sharks already aggregate. They were there first. Sharks might learn to come to a specific spot, but you’re not pulling animals in from hundreds of miles away. The degree of conditioning varies and is often less than people think. For white sharks in South Africa—more in sara’s wheelhouse—individual conditioning isn’t very strong; you might see it for a few weeks and then it fades. With some reef sharks, it can last longer, but again, those sharks were local anyway. When sharks do get bait and actually feed, the question is whether that changes total intake. We have some evidence that great hammerheads in the Bahamas may eat slightly more at feeding sites than in non-feeding habitats. In Florida, we estimate great hammerheads consume ~1% of body weight per day on average; at feeding operations it might be around 1.4%. So, a small change. Also, a few individuals can monopolize the bait, so not every shark present is getting extra meals. Could bait type matter for nutrition? Possibly. I haven’t seen much research on nutrient profiles, but ethically it makes sense to consider what you’re offering. Generally, operators use oily, bloody fishes sharks naturally prefer. Still, thinking about bait quality is reasonable.

Kas: We’ve seen projects where divers contribute photo-ID, log sightings, and note behavior. How has citizen science contributed to research and protection—and what are the benefits and drawbacks for shark science?

Cristina: I’m not sure I’m the best person to answer on data quality, but I agree with sara: seeing a shark isn’t counting a shark. With Caribbean reef sharks, tigers, and great hammerheads we work with, we recognize individuals by distinct features. Divers might see the same female pass three times on one dive and surface saying, “We saw three sharks,” when it was the same shark circling. Or the reverse—three individuals get lumped as one. For me, the value of citizen science is involvement. Even if the data aren’t perfect, people develop appreciation and a relationship with the animals. They surface asking, “What else can I do to help?” I tell them: you don’t need to remove hooks—start by understanding the ecosystem, adjust your diet, and support better legislation where you vote. Citizen science makes new divers more aware and engaged. However partial the contribution, that engagement is a net positive.

Yannis: From a science standpoint, the big advantage is volume. Scientists spend far less time in the water than people think; dive pros are underwater much more than we are. Citizen science can generate datasets we’d never collect ourselves. The downside is variable data quality—non-standardized, non-expert observations. Sometimes that’s fine; sometimes it’s not. The way past it is sheer volume. With small samples, errors matter. With hundreds or thousands of dives, the noise averages out, and you can model around it. I don’t do tons of citizen science work, but dive logbooks and similar efforts have been very useful for trends in relative abundance and change—information we couldn’t get alone.

Sara: I have mixed feelings because I’ve worked with these datasets. The big advantage—lots of data—is also the big problem: you still have to process it. AI tools that auto-screen photos are helping; manual photo-ID can be overwhelming and stall a project. Like shark diving, citizen science is fantastic when done correctly. It’s not enough to say, “If you see a tiger shark, send us your photo”—you’ll get 5,000 shots of the same animal taken within the same week. But if you coordinate with dive centers and ask a trained staffer to filter the best single ID photo per individual, that becomes usable. Pair it with education: taking a picture isn’t the same as doing science as it takes analyses and population estimate models to turn photos into actual data. I’m positive about citizen science—but it needs a clear understanding of its limits.

Kas: Yannis, climate change is altering temperatures and currents, shifting prey, and predator distributions. You track shark movements in large numbers. Have you seen behavior or range shifts linked to climate change? And what might this mean for divers?

Yannis: In my own datasets, not directly, but across shark-tracking studies we’re seeing shifts as oceans warm. Northern latitudes now include habitats that used to be too cold. On the U.S. East Coast, tiger shark tracks are extending farther north. Bull shark nurseries have been documented much farther north than before, and I’ve heard diver reports as far up as Rhode Island. On the West Coast, juvenile white sharks are also ranging farther north. Ecologically, more large predators enter areas where they weren’t common. For humans, shark bites remain very rare, but numbers are numbers: more people plus more sharks can mean slightly more interactions, even if risk stays low.

Kas: Are these movements adaptation, intelligence, or instinct?

Yannis: That’s behavioral plasticity. Mobile animals have preferred temperatures; when conditions change, they can move. Evolutionary adaptation is slower, and climate change is fast. It’s not that the absolute temperatures are unprecedented in Earth’s history—it’s the rate of change that’s the problem. It’s often too fast for many species to adapt genetically, so they rely on movement and flexible behavior if they can. Performance matters too: it’s not just “can they tolerate a temperature,” but “how well do they hunt, avoid predators, and compete at that temperature?” We’re working on ways to estimate performance–temperature relationships for sharks outside the lab to predict where they might go as waters warm.

Sara: Yes, we’re looking at genetics to gauge how adaptable different species may be to temperature shifts, and to predict which might cope and which won’t. If we can anticipate vulnerability, managers could reduce fishing pressure on the species least likely to adapt. That’s the theory; turning it into policy is another challenge. But genetics is a strong tool. Climate change isn’t a debate—it’s here. The question is how to mitigate impacts.

Kas: Let’s talk about safety and diving with sharks. In places like South Africa, the U.S., and Australia, shark attacks are a reality—mostly a function of more people in the water and, hopefully, more sharks. What’s a good strategy for sustainable long-term shark–human coexistence?

Sara: I’ll start. It’s a complex answer because it’s not just about numbers. Globally, there are roughly seven to eight shark-related fatalities a year. With sharks, only a few of roughly 500 species are involved in negative interactions, but fear drives calls to reduce sharks near tourist beaches—Australia, South Africa, Réunion, New Caledonia. Removing large sharks creates serious ecological problems. We must also acknowledge trauma, fear, and economic impacts after incidents. The best long-term solution is education: people fear what they don’t know. If we can teach when it’s wise to get in the water and when it isn’t, we reduce risk. And when incidents happen, context matters: time of day, weather, prey activity (e.g., sardines, dolphins), recent shark sightings. It stops being an “unprovoked mystery” and becomes a risk scenario we can understand and manage.

Yannis: In Florida you can have big sharks close to crowded beaches and often people don’t panic. That general acceptance—that we share the water and the individual risk is very low—is helpful, though it varies by location. After bites, the media want a tidy explanation; I’m cautious with that. Sharks are wild predators, and sometimes there isn’t a clear reason—these events are rare. You can lower risk by making smart choices about conditions and activity, but the ocean’s biggest danger is drowning, by far, not sharks. The ocean isn’t a swimming pool—there are rip currents and other hazards—yet when someone drowns (which happens far more often than fatal shark bites), we don’t develop a broad animosity toward the sea. In some places we’re starting to see a healthy acceptance of the inherent risks of going into the ocean; in others, less so. We should keep nudging that acceptance forward.

Note: The odds of being killed by a shark in the US are about 1 in 4,332,817. In comparison, the risk of drowning is substantially higher, and you are 1,817 times more likely to drown than to die from a shark attack. Florida Museum of Natural History

Kas:We’ve seen overfishing everywhere—of sharks themselves and of the prey they rely on. Could our overfishing make us prey? In other words, would making the water “safer” mean not reducing what sharks like to eat?

Sara: I wish we could use that argument to reduce fishing pressure, but it won’t work—it would just create more fear of sharks. We’re not part of their natural diet. So my short answer is no: they won’t “turn to us;” they’ll starve. If we keep hammering the oceans, we won’t create hungry sharks—we’ll create more dead sharks.

Kas: I get that. I was looking at it from a human perspective—when we’re hungry, we eat whatever we can, even risky things.

Cristina: This brings us back to a bigger point. Negative encounters involve a tiny fraction of shark species—you could count them on your fingers. Meanwhile there are 530+ other species that depend on fishes, mollusks, and the broader food web we’re depleting. Many live far from people, in deep water, and don’t prey on anything our size. Reducing the issue to “will sharks turn rogue?” is fear-mongering and misses the real damage we’re doing. Sharks range from pen-sized to bus-sized—neither end of that spectrum eats human-sized prey—but it all depends on healthy oceans and intact food chains. We should reduce fishing pressure for ecosystem health and sustainability, not because we make people afraid that sharks might target people.

Kas: Sharks are often called a keystone species—their presence or absence cascades through ecosystems. Final thought: what one message should every diver carry with them?

Cristina: The line I repeat is: sharks are vulnerable. Yes, they’re powerful and ancient—older than trees—but our overfishing and exploitation have made them vulnerable. Even if you live inland, remember: we made them vulnerable. Sharks don’t need us; we need sharks—for ocean health and for all the roles they play, not just as top predators. We should shift our perspective and act like we understand that, because our future is tied to theirs.

Yannis: Scientist hat on: most sharks aren’t “keystone species.” That’s a specific term and only a few qualify. That doesn’t mean they’re unimportant—far from it. Also, most sharks aren’t apex predators; many are mid-level predators and also prey for other animals, so their roles are complex. What I tell divers is simple: healthy marine ecosystems should have sharks. Outside of maybe Antarctica, if an ecosystem is in good shape, you’ll see sharks. In places with low human impact, the sheer number of sharks is striking—it hints at what oceans looked like before heavy exploitation. Baselines are tricky because we started studying after impacts began, but the pattern holds: where you see sharks, that’s generally a good sign.

Sara: You’ve covered most of it. For divers specifically: feel honored when you see a shark, any shark. I worry some big species are disappearing faster than we can study them. Seeing one is a sign of a healthier system—and a privilege. They often don’t care about us, but sharing the water with them is special.

Kas: Thank you all—truly. This has been a privilege.

Cristina: Thank you to Yannis and Sara. I’m not the scientist—I’m the one in the water the most. Marine biology isn’t mostly underwater time. It’s enriching to connect our experiences—science and practice—in ways that help sharks. Sara and I talk often, but Yannis, this has been an honor.

Kas: Sharks don’t have to be “keystones” to matter. Photo-ID studies, movement tracking, and seasonal patterns all say the same thing: healthy oceans have sharks, and responsible people meet them on the sharks’ terms.

We can move past stories to solid methods—know who you’re seeing before you count, tell behavior from numbers, and hold operators to the same standards as data. When we do that, ecotourism becomes a force for good, citizen science turns into real insight, and ocean protection doesn’t have to wait for the next crisis.

For divers—especially those running mixes and stages—carry this mindset topside and underwater: know your species, read the water, value regulation, and remember that “more sightings” isn’t a census. Climate change will keep redrawing the map; our practices and policies have to adapt just as fast. The ocean’s biggest risk remains drowning, not predators, but the biggest mistake is letting drama drown out data.

Leave with humility—and the privilege of knowing that every shark you see is both a sign of system health and a call to dive smarter.

On Shark Bites

by Cristina Zenato

“If we keep talking about the rare shark bites, they are no longer perceived as rare. I also disagree wholeheartedly with the use of the word “unprovoked.” With the little that people know about sharks and their behavior, what to us might feel as a harmless human action in the water might have been a trigger for a shark. “Provocation” is a negative word, because it indicates intent to hurt a “poor, not-doing-anything-wrong, person.” I believe that bites are “provoked,” even when we do not have the whole story or the full spectrum of circumstances. Simply put, on that rare occasion, the individual fulfilled all the requirements for a shark to decide to bite, something they do not do lightly. If we want to include shark bites, in cases involving spearfishers or similar situations, we should specify that there was hunting, fishing, baiting, or cleaning fish in the area. This is an aggravating circumstance, which doesn’t make the other bites unprovoked, only less explainable from the human observation point of view.”

Shark-diving good practices (5 quick tips)

- Choose operators with strong safety & ethics. Look for clear briefings, small groups, experienced guides, emergency oxygen/AED on board, radio/EPIRB, and transparent protocols for baiting/feeding (where allowed). Check recent reviews and confirm that they comply with local regulations and marine-park rules.

- Match the site to your experience. Many top shark dives (Cocos, Galápagos, Red Sea offshore) have currents, blue-water ascents, and depth. Be honest about your comfort level; consider training (Advanced, Nitrox, SMB use, drift skills) before booking.

- Follow the code underwater. Neutral buoyancy, stay low and calm, keep hands close, never touch or block a shark’s path, avoid rapid movements/vertical silhouettes, and always keep eyes on the water column (especially behind/above). Obey the guide’s positioning and exit signals.

- Gear for the conditions. Bring an SMB + spool, audible/visual surface signaling, reef hook where appropriate (Cocos/Palau-style sites), and exposure protection that matches local temps/thermoclines. For photographers: stow strobes when sharks approach closely to avoid bumps/entanglement.

- Respect wildlife & context. Don’t chase, corner, or harass animals. Skip spearfishing near shark sites. If chumming is used, understand the risk/ethics and the operator’s mitigation steps. Be aware of local advisories (e.g., seasonal closures, crime/travel notices) and ensure your travel insurance covers adventure diving and remote evacuations.

Enjoyed this read? Here are more stories that tie into it.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: THE TALKS: Italian Women Make Waves by Stratis Kas (2024)

InDEPTH: W I L D Life (2021)

InDEPTH: Best Fishes By Mon (2023)

Science Direct: Knowledge drives conservation: Tackling the shark consumption issue in Italy – A case study (2025)

Scientific Reports:The role and value of science in shark conservation advocacy (2021)

Cristina Zenato is a shark behaviorist, cave and ocean explorer, environmental conservationist, professional diver, photographer, speaker, and writer. Cristina is an advanced cave diving, rebreather, and mixed gas instructor and instructor trainer. She works with sharks in the wild and has spearheaded the campaign that resulted in the complete protection of sharks in The Bahamas. She has conducted the exploration and surveys of numerous new cave systems, which are now part of MPAs. Her work can be summarized in Exploration, Education, and Conservation. A member of the Women Divers Hall of Fame and The Explorers Club, she is a firm believer in the power of education and dedicates her time to teaching both above and below the water. Cristina is the founder of the nonprofit People of the Water, which is organized to expand the distribution of training, education, and research related to ocean and environmental issues.

Links:

People of the Water: https://www.pownonprofit.org

CristinaZenato.com: https://www.cristinazenato.com

Instagram @cristinazenato: https://www.instagram.com/cristinazenato

Facebook @CristinaZenatoExplorer: https://www.facebook.com/CristinaZenatoExplorer

X (Twitter) @cristinazenato: https://twitter.com/cristinazenato

LinkedIn @cristinazenato: https://www.linkedin.com/in/cristinazenato

Dr Sara Andreotti is a marine biologist and highly regarded lecturer at Stellenbosch University, working since 2009 toward a global, long-term management and conservation plan for sharks. She completed her PhD at Stellenbosch in 2015, using genetic analyses and photographic identification to assess population size, structure, and dispersal of South African white sharks—producing the first national assessment of their numbers and genetic makeup. Her genetics program has since expanded through international collaboration with the University of Queensland and Flinders University (Australia). A committed supervisor and mentor, she has graduated three master’s students and one honours student in the last two years and, in 2022, co-founded the SharkWise Project Marine Internship Program to provide practical training and logistics for young scientists. Driven by conservation impact, Sara co-founded SharkSafe Barriers (Pty) Ltd and is COO and a founding director. She is one of four co-inventors of the patented SharkSafe Barrier™, a kelp-forest-mimicking, magnet-based technology designed to deter large predatory sharks without harming other marine life—advancing peaceful coexistence for swimmers and surfers while supporting coastal ecology and tourism.

Links:

SharkSafe Barrier Pty

Website: www.sharksafesolution.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Sharksafebarrier/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/sharksafe-barriers-rf-

Twitter: https://twitter.com/SharksafeB

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sharksafebarrier/

YouTube (SharkSafe Barrier’s Channel): https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCSarwwrn_24IdVmbnLpPhhA

Dr. Sara Andreotti

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sara.andreotti.79

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/sara-andreotti-b044106/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AndreottiSara

Dr. Yannis P. Papastamatiou is an ecologist specializing in the behavior, ecology, and conservation of sharks and other marine predators. He earned degrees in Oceanography (Southampton, UK), Biology (California State University Long Beach), and a PhD in Zoology (University of Hawaii). His research combines biologging, telemetry, and field studies to reveal the hidden lives of sharks and their roles in marine ecosystems, spanning systems from the Pacific to the Caribbean. He also studies the ecology of mesophotic reefs (reefs deeper than 50 m/164 ft). Yannis is an Associate Professor at Florida International University, where he leads the Predator Ecology and Conservation Lab. He has published over 130 peer-reviewed papers in leading journals including Nature, Science, and Biological Conservation. His work has been supported by major organizations such as the NSF, NOAA, and National Geographic Society, and is regularly featured in documentaries on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, and the Smithsonian Channel. An experienced scientific and technical diver and mentor, Yannis has supervised students worldwide and continues to inspire future generations of marine biologists while emphasizing the urgent need to conserve ocean ecosystems.

Links:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/yannispapastamatiou

X (Twitter): https://twitter.com/Dr_Yannis

Lab website: https://www.peclabfiu.com

Lab Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/peclabfiu

Lab X (Twitter): https://twitter.com/peclabfiu

Stratis Kas, a Greek-Italian professional diving instructor, photographer, film director, and author, has spent over a decade as an esteemed Advanced Cave instructor, and has led expeditions to extreme locations worldwide. His impressive diving achievements have solidified his expertise in the field. In 2020, Kas published the influential book Close Calls, followed by his highly acclaimed second book, CAVE DIVING: Everything You Always Wanted to Know, released in 2023. This comprehensive guide has become a go-to resource for cave diving enthusiasts. Kas’s directorial ventures include the documentary Amphitrite (2017), shortlisted for the Short to the Point Film Festival, and Infinite Liquid (2019), which explores Greece’s uncharted cave diving destinations and was selected for presentation at TEKDive USA. Kas’s expertise has led to invitations as a speaker at prestigious conferences including Eurotek UK, TEKDive Europe and USA, Tec Expo, NSS-CDS Cave Diving Conference and Euditek. For more information about his work and publications, visit stratiskas.com.