Latest Features

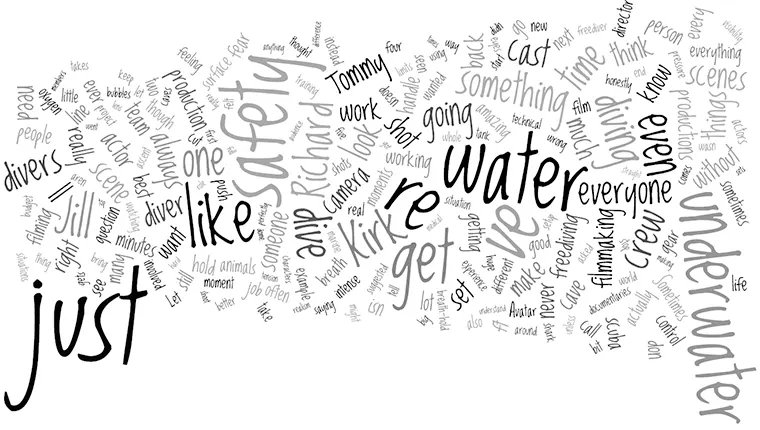

Big Screens, Deep Waters: The Evolution of U/W Storytelling

A Round Table Rhetoric with Stratis Kas

Featuring:

🎶 Predive clicklist: Morricone: Theme from Cinema Paradiso (Renaud Capuçon)

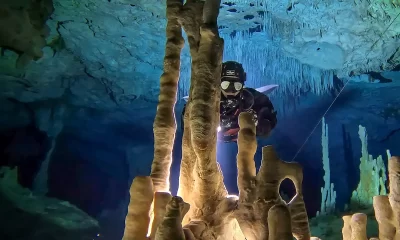

Underwater filmmaking has always been a blend of art and challenge, but this episode of The Talks takes it to a whole new depth—right into the realm of professional blockbuster cinematography. We’re moving beyond the hobbyist lens and indie passion projects to the high-stakes world where underwater scenes shape Hollywood epics, documentaries redefine boundaries, and technology blurs the line between reality and spectacle.

This isn’t just about getting wet and pressing record. It’s about orchestrating massive productions at the margins of safety, where technology meets artistry, and when even the smallest misstep can cost a fortune—or worse. In this roundtable, we’re diving into the minds of four industry titans: Jill Heinerth, Kirk Krack, Richard Stevenson, and Tommy Vuylsteke. These are the people who make the impossible look effortless but will be the first to tell you that nothing about underwater filmmaking is easy. They’ve fought to ensure safety protocols are followed even when the budget says otherwise. They’ve challenged directors to rethink their misconceptions about diving.

We’ll explore how they bring cinematic visions to life, whether it’s managing complex stunts with dozens of breath-hold performers, navigating the ethical dilemmas of portraying marine life, or mastering the technical demands of underwater cinematography at the highest level. This is about raising the bar—not just for underwater filmmaking but for how we think about the art, science, and responsibility of capturing the ocean’s beauty.

Welcome to a new frontier of storytelling. This is The Talks—Big Screens, Deep Waters: The Evolution of Underwater Storytelling!—Stratis Kas.

Stratis: Thanks for being here, everyone! Cinema is my biggest passion…unless I’m talking about diving—then, hands down, that’s my biggest passion! This project is all about blending these two worlds. I wanted to showcase just how different things look when top pros are in productions that involve diving. Diving isn’t just a backdrop; it impacts every part of production—safety, cinematography, and more.

Let’s dive in: Have you or your crew ever felt tempted to push safety boundaries for the perfect shot? Not anything extreme, but those moments where you think, “Just a bit further for that angle.” How do you handle pressure from those who might not understand diving’s limits? And what are your non-negotiables when it comes to safety on set?

Kirk: Definitely. There are moments when filming pushes the boundaries, and it’s all about knowing when to push back and when to adapt. A straightforward example in water work is medical clearances for cast and crew. Depending on the jurisdiction, there can be strict medical requirements that could disqualify someone. In other places, there’s a bit more flexibility. When dealing with A-list cast, sometimes they’re not thrilled about going through the medical checks or sharing personal health info, which can create some resistance. But we’ve always managed to work it out.

Another big one in diving is the golden rule: Always breathe and never hold your breath on scuba (unless you’re freediving—then it’s the opposite!). Sometimes, though, for a specific shot, like an ascent without bubbles, you have to tweak that rule. You set up on scuba, prepare everything, and then do a controlled breath-hold ascent. For example, on Avatar, we needed to shoot ascending scenes without bubbles, so we adapted by going through levels of exhalation, blending freediving techniques with scuba to safely pull off the shot.

There was also a time when I suggested using technical freediving instead of scuba for a scene. They were planning to shoot everything on scuba with breath-holds, but I suggested we actually train the cast in freediving using a 50% oxygen mix for its benefits and no risks. However, local regulations didn’t allow nitrox for occupational diving. But because the jurisdiction didn’t cover breath-hold diving, we got around it by breathing up on the 50% oxygen on the surface without compressed gas concerns. So, there are workarounds, especially when adapting freediving techniques into a primarily scuba-oriented setup. It can involve educating the team and sometimes challenging assumptions.

Jill: There are a lot of different players involved in film production, and most of them aren’t divers. Insurers, producers, and execs often have a vision of what they want, but they don’t necessarily know how to do it safely. Even among the crew, there can be different priorities. For instance, I worked for years with Wes Skiles, often as the producer with him directing. I remember during team training in the Rockies, I asked someone for feedback, and they told me, “If the producer and director aren’t clashing now and then, someone isn’t doing their job.” The director’s priority is getting the best footage while the producer balances that with safety—making sure the safety divers are on point and that no one gets hurt. That tension is a healthy part of the process because, without it, you’re probably missing something critical. On almost every shoot, I end up doing a lot of educating to make sure everyone understands the safety framework.

Thanks so much, Jill! Your answer sets me up perfectly for Richard with my next question, which I like to call the “underwater boot camp.” Shooting underwater isn’t exactly an everyday thing, so how do you get the cast and crew up to speed? I imagine your crew is probably with you full-time or pretty close, so they’re used to the flow. But what about the cast? Do you have any training sessions to get everyone ready for these unique conditions? How do you handle actors or crew who need to stay immersed for extended takes?

Richard: We’re pretty lucky in the UK because our teams are split into two main areas: the camera team—where I step in—and then a whole separate department that deals with all the challenging situations you just mentioned. While I’m not directly responsible for handling cast in the water, I’m very much involved when it comes to filming them. It’s fascinating to see how different marine coordinators manage cast and crew, especially if someone’s feeling uneasy in the water or isn’t very confident—and they know everyone’s watching. Imagine being in front of a crew of 300 with all eyes on you; it’s intimidating. I’ve seen some of the best coordinators work with cast who are struggling, and the old “shout louder until the job gets done” approach just doesn’t cut it anymore. It’s about stepping back, talking it through, rehearsing in a smaller, closed set, and gradually building up to the full scene.

Tommy: Absolutely, reading the person in front of you is key. Some actors are really comfortable in the water and can handle quite a lot, while others struggle. After some training, you can usually tell, “Okay, this person might be good to go down three or four meters a few times, but others may not be able to handle that at all.” And with a huge crew around, the pressure is intense. So, it’s crucial to ease them into it—don’t just jump straight into the deep end with complex shots. Build up their comfort level gradually, and they’ll get more at ease. Sometimes directors don’t fully understand what’s possible underwater or the limitations. I once had a director ask if we could do an emergency ascent—just a straight 10-m/30 ft rush to the surface on the fly. I had already been diving for half the day, and transitioning straight to freediving isn’t ideal in those situations. So, you have to explain the physical limits and timing involved, which isn’t always easy for people who don’t have that background.

Another factor is water temperature. For example, if it’s just 5° C/41° F , you’ve got maybe five minutes tops if someone’s not in a wetsuit, and that can go quickly. There’s also the safety aspect of knowing how many takes you can realistically get before you have to call it. So, ideally, they bring us in early to discuss these limitations upfront so everyone’s on the same page and we can avoid last-minute surprises.

Kirk: If I can jump in here, I think it’s worth noting that you can have a super knowledgeable production team and director—or, you know, the exact opposite. On Avatar, I had the chance to work with James Cameron, arguably the world’s top expert when it comes to water scenes. I was given a tremendous amount of time to help the cast develop their characters. Interestingly, some cast members were naturally strong in the water, but their characters were supposed to look inexperienced. On the other hand, I had cast members with real water phobias who were playing characters born and raised in the water. Working with people like Cameron and the team at Lightstorm, who have deep water knowledge, gave us the time to develop everyone fully. But then, on other productions, it’s like what Tommy said—you get very little time and are just pushing to get the minimum you need to make the shot work rather than getting the best out of the actor. That difference really shows on screen. In Avatar, every water-based scene was genuinely performed in the water. That’s only possible because we had months of training time, working through stunts and performance capture in the water. That level of preparation—that’s the ideal setup.

Quick sidebar—Recently, I heard about a cave diving documentary where the production team kept pushing for more drama, asking, “Can you make it look dangerous?” They even suggested creating zero visibility in a perfectly clear, massive 60x60x100 m/200x200x330 ft tunnel. Of course, the divers weren’t about to kick up silt or dive to 80 m/260 ft just to manufacture chaos. This demand for dramatization is common. For example, while adapting my book Close Calls into a series, the production team asked, “Can we show the exact moment of the incident?” But these weren’t planned events—there’s no footage. Unlike climbing or mountaineering, where tension is visible, underwater scenes often look calm, even during intense moments. For non-divers, it’s hard to grasp why it doesn’t naturally appear more dramatic on screen.

That brings me to Jill. Dive safety is a huge focus for you, and I think dive safety officers are unsung heroes. You’ve taken on this role—officially and unofficially—on many productions. What’s it like to be the one responsible for everyone’s safety on set?

Jill: I’ve been a dive safety officer and coordinator, planning safety protocols and operational practices for shoots—and honestly, it’s incredibly stressful. Looking back, I appreciate the role even more but, in the moment, it’s intense. I remember one project that was written by non-divers but focused on cave diving with scenes in both natural caves and on sets. They wanted me to oversee the safety of anyone in the water, which involved complex stunt work across multiple sets—waterfalls, cave environments in pools, wild caves, the works. I told them I’d take the job, but only if I had the authority to call “cut” if I saw any danger. They initially refused, saying a cut could cost hundreds of thousands. My response was, “I’ll only call it if someone’s about to get hurt or worse. Without that authority, I can’t take the job.” It took months of negotiations, but they finally agreed, and I did end up using it—to prevent an accident, not just disrupt filming.

Richard: That’s why here in the UK, we’ve really nailed down the separation of roles—camera and safety operate as distinct teams. Having a dedicated safety person who’s not worried about capturing the shot, just focused on dive safety, has made a huge difference. It keeps the pressure manageable and really improves safety on set.

Jill: You guys are doing it right. But unfortunately, a lot of productions today are running on tight budgets, and that’s where issues arise. I’ve had productions try to hire me as a camera operator without budgeting for a safety diver. I’ve had to tell them, “If there’s no budget for safety, there’s no budget for the film.” Sadly, there’s always another crew willing to cut costs on safety. As professionals, though, we have to draw the line and insist on the necessary precautions. There have been too many incidents where camera operators or essential crew members have been hurt, so it’s crucial to protect everyone involved—from crew and cast to the safety divers and even the person in charge who may be under pressure but is not exempt from safety requirements.

Tommy: Absolutely, prevention is key. I think we’re all getting better at predicting issues before they happen in the water. For instance, if an actor has to fall from above into the water and sink, the director might say, “Let’s see them drop deep.” But we know a normal person needs to equalize their ears after just a meter or two. I need to know if the actor can descend without equalizing visibly, or it’s going to ruin the shot. If they tell me it’s a stunt person, I still need to check—can this stunt person actually go five meters without equalizing? And if they can’t, then we’re wasting time because we’ll have to work around it. It’s so much better to address these things in advance instead of just seeing what happens on the day.

Strategy is key, and experience matters. On a recent production, I was suggested filming on a single set in Europe and using actors for underwater scenes. I argued for real locations and trained divers—they bring authenticity and realism you can’t fake. In your experience, how vital is it to use real divers for these scenes?

Tommy: Great question, and honestly, I deal with this a lot too. Just a couple of weeks ago, I was in a situation where there wasn’t enough budget to use a new high-tech studio in Brussels, so we had to improvise. They wanted a dive scene on a wreck—going inside, searching for something, finding drugs, bringing it up—and they wanted the real actor to do it. I asked, “Is he even a diver? What can he handle?” With divers, you get technical skill, but they don’t have that same ability to convey emotion underwater. There’s no visible facial expression through the mask, no way to show eyes and mouth. An actor, even without much dive experience, can project urgency or emotion, even without showing their face directly. So it’s always a balance—teach the actor to dive or use a diver? In this case, the actor was actually a diver, so we went with him for the wreck scene. The dive was 15 m/50 ft, manageable for a trained diver, but the water was 13° C/55 °F, so we checked his gear. He had a 7mm suit, so we planned for a max of 30 minutes per dive and split the shots over two dives. It all depends on the circumstances; sometimes the actor works, other times a diver is best.

Kirk: What Tommy’s saying is spot-on. You can go with the actor or the diver, but I always think about who’s watching. I want it to look real, not just for the general audience, but for someone like Jill, James Cameron, or any other water experts in the audience. I want them to believe it, not roll their eyes. Personally, I find it tough to sit through water movies because I see every detail so critically. Like Aquaman—I couldn’t even finish the first one. I almost walked out five minutes in because the lack of realism just drove me nuts. And that’s the difference between productions led by water people and those that aren’t—they settle for “good enough,” but for me, it’s never good enough unless it feels authentic.

Alright, next time we’re all together, we’re making a weekend of this. Barbecue, all the water movies Kirk hasn’t seen, and we’re watching his reactions.

Richard: Aquaman marathon it is—sounds like a plan!

Moving on to my next question for Richard. This one’s about your role as a filmmaker: have you ever been asked to create an underwater scene that’s completely unrealistic—just for the sake of looking cool on camera? Is there a line for you between making something visually stunning and keeping it believable?

Richard: That’s a tough one! I mean, if I say 90% of my underwater scenes aren’t realistic, I might never get hired again! But, yes, there have been moments where I’ve thought, like Kirk was saying, “Guys, if we’d just slowed down or spent a little more time on this…” I won’t name names, but there was one film where we had a sunken airplane at a 45-degree angle. The set wasn’t actually tilted, so we had to tilt the camera instead. But no one thought about the bubbles—they were coming out at an angle that totally gave away what was going on. The bubbles are like nature’s way of showing what’s up and down! Sometimes, you do your best to maintain realism, but when the higher-ups push for speed, you just have to get it done. That’s the brutal truth.

Jill: That reminds me of a time working with Wells. I was holding back because of safety issues, and he just looked at me and said, “Just let me make my epic movie!” I guess that tension means we’re both doing our jobs right.

So, Kirk, sticking to the theme here—underwater filmmaking is full of wild, uncontrollable variables. Have you ever had a moment where you just had to let go? Not in terms of compromising safety or integrity, but more from a creative standpoint—just releasing that need for control. And did that decision ever shift your perspective on diving or even life itself? Yeah, we’re getting a bit spiritual here.

Kirk: Honestly, I’ve been lucky. In most of my movies, I’ve never had to fully give up creative control. Most of my big projects have been tank work, and for documentaries or ocean scenes, I haven’t really had to make any big compromises.

Richard: Same here. Thankfully, we often get the time we need to make things look right. Sometimes the weather’s against us on location, and in those cases, we’ve had to reshoot or even scrap it entirely and come back later. It’s a huge decision and cost, but sometimes it’s the only answer.

Kirk: But here’s something that gets me—there are scenes I thought would look incredible, beautifully shot, and they just get cut from the final movie! I’ll be watching the edit, thinking, “Why didn’t that make it in?” It’s like a great scene just thrown out, and I’m left wondering why.

Richard: Kirk, that basically sums up my career! So many amazing shots end up on the cutting room floor.

Alright, here’s a fun one—what’s the one underwater film cliché that drives you crazy? That one scene or misconception you wish directors, producers, and writers would stop including?

Kirk: The free diver doesn’t always have to die in every movie! We can do more than just look good and then drown. Freediving is an amazing sport with so much to offer. Let’s give audiences something inspiring instead of just another tragic ending.

Jill: For me, it’s the line, “He ran out of oxygen.” Even when we correct it, they still write “oxygen tank.” It’s a constant battle to get them to understand!

Maybe we should just give in and start diving with actual oxygen tanks—just to keep things “realistic.”

Tommy: This is such a great question because, honestly, once things start going wrong underwater, it quickly gets intense. Last year, I spent six months filming a documentary about Alexey Molchanov, the world’s best freediver. This guy dives to 156 m/512 ft and wanted to reclaim all his records in one season, aiming for new records in every freediving discipline. Everything went perfectly—monofin, no fins, free immersion—until we were in the Bahamas. He was coming up from a no-fins dive at 100 m/330 ft, and at 30 m/100 ft, he blacked out. I was there at 30 meters, filming, but couldn’t do anything since I was on my scuba rig. Luckily, his safety divers were there, and everyone was fine, but suddenly, everyone on set was saying, “Now we have a story!” Because things going wrong adds drama; and, underwater, it seems like trouble, misery, and danger are what people want to see. There are so many beautiful things underwater, but even when it’s just animals, it’s like they want something intense—next thing you know, they’re filming them eating each other.

Kirk: Exactly—it’s this constant push for over-dramatization. As free divers, we know that if we push a little too far and black out near the surface, it’s usually no big deal. But in film, it becomes this exaggerated, life-or-death scenario. And it’s frustrating because freedivers are shown as constantly on the edge of disaster, when, really, it’s more like a boxer getting knocked out—you recover and keep going.

I think part of it goes back to our primal fears: falling, getting eaten, and suffocating. Freediving taps into that suffocation fear. People hold their breath for 30 seconds, feel that urge to breathe, and imagine freediving as this desperate, near-death struggle. But when you’re trained, it’s just not like that. And it’s frustrating that even documentaries can play into these fears instead of showing the reality. We have genuine risks, like Jill’s cave dives, but those are managed, understood, and under control. For the public, though, it’s all drama. I get it—you want to sell the story, but it doesn’t always reflect what we’re actually doing.

Jill: One of my pet peeves is the gear they sometimes want us to wear. I’ve been handed these tiny, jelly-yellow split fins for a high-flow cave because “they’ll look great on camera.” Or on my first TV gig, they gave me this pink floral lycra suit, which looked cool, but I was about to spend eight hours in chilly water! I said, “No way, I’ll be hypothermic.” And they’re like, “But it’ll look amazing!” Yeah, amazing and freezing!

Kirk: Exactly! Sometimes productions just don’t listen to us. Like, if we’re going to be in the water for hours and the character’s supposed to be in a loincloth, that water better be 32-33° C/90-91 °F, and we’ll need a hot water hose nearby to warm up between takes. But you get there, and the water’s just “pool temperature” because the coordinator figures, “People swim here all the time.” It’s like, why did you hire us if you’re not going to take our expertise seriously? Why did you hire us?

Excellent, Richard, you’re up next! Let’s shift gears just a bit. Diving can be exhilarating, but it can also bring fear bubbling to the surface—sometimes unexpectedly. Have you ever had a moment underwater, while working, where fear hit you hard? How did you handle it? And did it teach you anything about yourself?

Richard: Honestly, no, not while working. I’ve never felt fear or a sense of foreboding on the job. If that were to happen, I think it would mean something’s gone seriously wrong—like we’ve crossed a line that shouldn’t have been crossed. Recreationally, though? Plenty of moments. I’ve had a few “chats with myself” when I’ve been stuck or temporarily misplaced in caves—let’s call it at that. But at work, it’s different. Everything feels controlled and calm. I know it’s a dull answer, but if fear creeps in on a professional dive, something’s definitely out of place.

That’s fair! My question comes from personal experience. During a routine cave diving course with a military pilot—one of my favorite students—I called the dive just minutes in because I had a bad feeling. He was confused, and I debated whether to explain or make up a technical issue. I chose honesty, and we’re still friends to this day. It reminded me of Jill’s advice at a Baltic tech event: Always trust that little voice. That moment stuck with me, even though nothing went wrong.

Richard: That reminds me of something—not work-related, but similar. We were cave diving in France, and I noticed my dive buddy sitting in the entrance pool, pre-breathing his rebreather. He was swaying slightly, looking clammy and pale. He turned to me and said, “I’m just hot, I need to get in the water.” But something felt off, so I stopped him and told him to hold up for a minute.

Turns out, he’d forgotten to put the canister in his rebreather—pretty critical gear! He was ready to head into the cave to “cool down,” which would have been disastrous. I had this weird gut feeling that something wasn’t right, and thankfully, I acted on it. So yeah, it’s a story that kind of lines up with yours, though again, I’ve never had that happen while working.

Kirk: So, Avatar. We had up to 26 people underwater on breath hold at once, with waves, currents, high-speed scooters, jet evaders—it was a lot. At first, it was all about control, juggling everything—managing the environment, the divers, the equipment. Then more elements would get thrown in, and you’re still juggling, still managing. But eventually, it starts feeling like you’re losing your grip on the whole situation.

It wasn’t fear exactly, but there were definitely moments where I thought, “Okay, we’ve hit the limit here.” That’s when we’d finish a shot and call a hard stop. We’d take a break, reset, and recalibrate. Too much was happening too fast, and the protocols and spatial awareness needed to catch up.

One thing that really helped on Avatar, since it was primarily a breath-hold film, was taking “action” out of the director’s hands for those sequences. Instead, we had countdown clocks around the tank. We’d coordinate with the actors and divers, set the breath-up time, and get everyone synced. I’d go to the principal actors and say, “Are we good on this mixture? We’ve got four minutes.” Then we’d start the clock. Production had to synchronize with us.

When the clock hit five, four, three, two, one, we’d all take our last breath and descend. In the 30 seconds before that, production would spool up and get everything aligned. But as the tempo picked up, suddenly four minutes turned into two minutes, and things would get hectic. That’s when you just have to stop, reset the juggling act, and then dive back in. It’s all about knowing when to pause and realign.

Alright, here’s a question for everyone. A lot of films claim to respect marine life, but when there’s money on the line, how often do those promises actually hold up? Have you ever encountered practices in water-based filmmaking that felt straight-up harmful or irresponsible? And on a related note, animals don’t exactly follow scripts—have you ever had to “direct” marine life or manipulate a scene involving underwater creatures?

Jill: I had one project in an aquarium for a “reality” TV program. The idea was that someone was going to jump into a tank with a shark to face their greatest fear. I was really uncomfortable with how the shark was being handled. The handler, who was supposedly an expert, kept antagonizing the shark, and it created a dangerous situation for the crew, the talent, and myself. I ended up calling it and pulling everyone out of the water. We had a heated argument at 3 a.m., but I stood firm. Eventually, the wrangler agreed to back off unless there was an actual life-threatening emergency. The whole thing left me feeling awful—about the shark being in an aquarium, how it was treated, and the situation overall. I’ve never taken another job like that since.

Tommy: I’ve been lucky to have amazing encounters with animals in open water—just me, maybe a safety diver, and a local guide. But I’ve also seen things that bother me. On live-aboards, for example, I’ve seen 15 divers pile into the water on top of a manta ray, overwhelming it just to get their pictures. As a filmmaker, I can control my impact—I know my limits and where to stop. If someone pressures me for closer shots or more action, I’ll discuss what’s possible, but I won’t push the animals or myself into situations I’m not comfortable with. Sadly, I see tourists going way too far all the time.

Kirk: I’ve worked on documentaries over the years with various animals, and it’s always a moral dilemma. As a regular diver, I wouldn’t chase an animal for a closer look, but with a camera, you start justifying it: “This is for the greater good—to show this animal to the public and foster appreciation for it.” It’s a slippery slope. Sometimes, what’s acceptable in filmmaking crosses a line that wouldn’t be okay for the average diver, and it’s something I think about often.

Jill: We’re definitely at an interesting point in filmmaking and conservation. Back in the early Cousteau days, it was all about “Look at this! We’ve never seen this before!” Then we moved into exciting, experiential storytelling. Now, we’re shifting towards being better stewards of the planet. Personally, my environmental ethics have evolved throughout my career. I just came back from a conference focused entirely on ethical procedures in wildlife filmmaking—something I couldn’t even imagine happening years ago. Laws are also changing; in many places, you can’t approach whales or other animals as closely as before. We’re learning to model more responsible behavior, and I think that’s the direction we need to keep moving in.

It does feel like our craft is evolving, doesn’t it? This is an important discussion. Favorite piece of gear right now?

Kirk: My best and most essential piece of “gear” is my 7.5-liter lungs. They let me dive on breath hold, move between the surface and depth quickly, and avoid decompression or long ascent times. In many situations, I can do things on breath hold that would be cumbersome with scuba. For me, having a freediver on a production is invaluable—they can bridge the gap between the surface and depth much faster, cover more ground, and handle dynamic tasks. So yeah, being a freediver on set is like being the ultimate underwater multitasker.

A diving busboy, basically. Love it.

Richard: My favorite piece of gear right now is a bit more materialistic: controllable underwater lighting. It’s been a game-changer. Instead of yelling at the crew to adjust the lights, I just turn a dial and control everything myself. It’s made my life so much easier.

Jill: I’m currently obsessed with a little lighting rig I put together for working in super low-visibility caves. I built a kind of chandelier setup with lights and instruments hanging off it, all attached to a lift bag. It floats right above whatever I’m working on, giving me perfect illumination in less than a meter of visibility. It’s been an absolute game-changer!

Tommy: I’m all about my Nauticam housing with a special wide-angle dome port. It’s heavy—like 10 kg/22 lb—but it turns my lens into something much wider. For instance, a 16-35mm lens becomes closer to a 10mm. Where I’m based, in Belgium and the Netherlands, the visibility is awful. But with this setup, my camera sees more than my own eyes can. I’ve gotten footage in terrible visibility that looks amazing—people are like, “Wow, that’s beautiful!” and I’m thinking, ”I didn’t even see that clearly.” Recently, I used it for a scene with a freediver and sperm whales in Mauritius. Without this wide-angle dome, I wouldn’t have been able to get the full whales in the shot. If I’d backed up, the extra water would have made everything dark, and I’d lose the detail of their gray tones and textures. This dome lets me stay close, keep the detail, and still get those epic shots. It’s honestly been a lifesaver for my work.

What an incredible conversation this has been. I want to sincerely thank Jill, Kirk, Richard, and Tommy for sharing their insights, stories, and expertise today. From the challenges of blending creativity and safety to pushing the limits of technology and ethics in underwater filmmaking, your experiences highlight what makes this craft so unique and inspiring.

To our audience, I hope this discussion has shed light on the dedication, ingenuity, and responsibility that go into creating the stunning underwater scenes we all love. Behind every breathtaking shot is a team of professionals navigating a delicate balance between artistry, science, and conservation. Let’s not forget the importance of respecting the underwater world that gives us so much.

As filmmakers, divers, and storytellers, we are constantly evolving—embracing new tools, refining our methods, and deepening our commitment to the planet. Thank you for joining us on this journey. Stay curious, stay inspired, and as always, dive responsibly. Until next time!

FILM LINKS: THE TALKS CINEMA

Jill Heinerth

Jill Heinerth, celebrated for The Cave (2005), Real Sobriety (2009), and We Are Water (2013), takes center stage in Diving Into The Darkness. This captivating film delves into her life, showcasing the awe-inspiring risks and challenges she has faced in exploring uncharted underwater worlds.

Trailer courtesy of Running Cloud Productions.

Diving Into The Darkness and its trailer are © Running Cloud Productions. All rights reserved.

Kirk Krack

Renowned for his work on Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022), Avatar: The Way of Water (2022), and Suicide Squad (2016), Kirk Krack also trained stars for the underwater scenes in Avatar: The Way of Water.

Clip courtesy of 20th Century Studios.

Richard Stevenson

Known for his contributions to No Time to Die (2021), Swimming with Men (2018), and Freeze the Fear with Wim Hof(2022), Richard Stevenson has left a lasting impact on cinematic underwater sequences. Watch the trailer for No Time to Die below:

Trailer courtesy of 007.com and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc.

No Time to Die and its trailer are © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All rights reserved.

Tommy Vuylsteke

We had the chance to sit down with underwater cinematographer Tommy Vuylsteke, who, alongside Pieter Germeys, shared fascinating details about their work on the film Freediver. Check out the breathtaking visuals they helped create in the official trailer below:

Trailer courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

Freediver and its trailer are © Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: THE TALKS #1: Cave Diving Nomads

InDEPTH: The TALKS #2: Leaders of the Pod

InDEPTH: The TALKS #3: Diving Deep into Science

InDEPTH: The TALKS #4: The Art & Practice of Cave Photography

InDEPTH: THE TALKS #5: Real vs. Reel: How Influencers Shape the Dive World

Jill Heinerth

Underwater Explorer, Filmmaker, Author, and Advocate

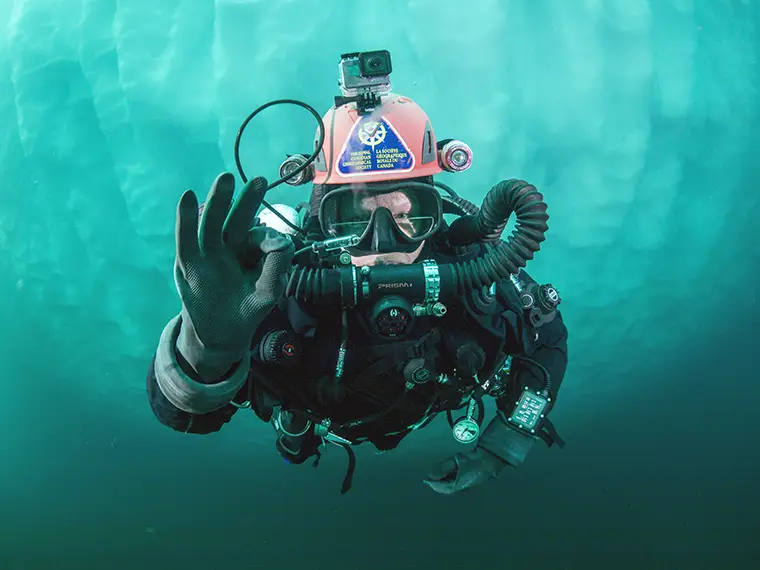

Jill Heinerth, FRCGS, D. Lit. h.c., is a groundbreaking underwater explorer and one of the most accomplished divers in history. As the Explorer-in-Residence for the Royal Canadian Geographical Society and the Honorary Ottawa Riverkeeper, Jill’s career spans decades of boundary-pushing dives, scientific exploration, and groundbreaking storytelling. She is the author of Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver, an acclaimed memoir detailing her extraordinary adventures and her unshakable commitment to conservation. Jill has received numerous accolades, including the Sir Christopher Ondaatje Medal for Exploration, and is a Fellow of the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame, the Explorers Club, and the Women Diver’s Hall of Fame. Through her photography, films, books, and public speaking, Jill inspires global audiences to confront the challenges of climate change, protect water resources, and explore the unknown. From historic dives in Antarctica to the digital mapping of Florida’s caves, Jill’s work showcases her relentless drive to illuminate the hidden depths of our planet.

FILMOGRAPHY AND HIGHLIGHTS:

Groundbreaking Explorer:

Pioneered some of the most extreme underwater dives in history, including being the first to cave dive inside an iceberg in Antarctica.

Acclaimed Author: Wrote Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver, an award-winning memoir that reveals the challenges and beauty of underwater exploration.

Filmmaker & Photographer: Created stunning visual storytelling for National Geographic, BBC, and other global media platforms, documenting underwater environments with unmatched expertise.

Conservation Advocate: Honorary Ottawa Riverkeeper and a passionate advocate for water resource protection and climate change awareness.

Award-Winning Career: Recipient of the Sir Christopher Ondaatje Medal for Exploration and a Fellow of the Explorers Club, Women Diver’s Hall of Fame, and the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame.

Digital Innovator: Worked on creating augmented reality models of Mayan artifacts and digital mapping of underwater caves, blending exploration with cutting-edge technology.

LINKS:

Website: DivingIntoTheDarkness.com

Website: IntoThePlanet

Website: Jill Heinerth-Fine Art of Exploration

Email: [email protected]

Facebook: Jill Heinerth

Facebook: Jill Heinerth-Into The Planet

Instagram: @jillheinerth

YouTube: Jill Heinerth-Into the Planet

X: jillheinerth

Linked in: Jill Heinerth, FRCGS D. Lit., h.c.

Kirk Krack

Pioneering Freediver, Marine Human Performance Specialist, and Film Consultant

Kirk Krack has spent over 35 years redefining the limits of human performance in the water. As a multi-disciplined diver, trainer, and entrepreneur, he bridges the worlds of recreational, technical, and freediving with unmatched expertise. Kirk has trained seven athletes to achieve 23 world records in freediving, coached elite military special operations units, and helped shape the future of underwater human potential. In 2016, he was honored as the DAN Rolex Diver of the Year for his contributions to dive safety and education. Kirk’s impact extends far beyond diving. He was a critical member of the Oscar-winning team behind The Cove and contributed to Racing Extinction with the Oceanic Preservation Society (OPS). Hollywood has also tapped into Kirk’s expertise—he trained Tom Cruise and Rebecca Ferguson for Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, Margot Robbie for Suicide Squad, and the cast and crew of James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water and its sequels. Now, as Human Performance Diver Lead at the UK-based DEEP Research Labs and DEEP Institute, Kirk focuses on developing underwater habitats and advancing human marine performance, paving the way for a sustainable human presence in the oceans.

FILMOGRAPHY AND HIGHLIGHTS:

IMDb: Kirk Krack

Elite Trainer: Coached military special operations teams and seven freediving athletes to 23 world records.

Award Winner: First freediver to receive the DAN Rolex Diver of the Year award for his contributions to safety and freediving.

Hollywood Consultant: Trained cast and crew for major films, including Avatar: The Way of Water and Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation.

Documentary Work: Collaborated on The Cove and Racing Extinction, two groundbreaking films raising awareness for ocean conservation.

Innovator: Leading the charge in underwater human performance research and sustainable ocean habitats with DEEP Research Labs.

LINKS:

Email: [email protected]

Richard Stevenson

Underwater Cinematographer and Extreme Environment Filming Specialist

Richard Stevenson has been a cornerstone of underwater cinematography since 1995, bringing a unique blend of creativity, technical skill, and deep-sea expertise to TV and film productions worldwide. An accomplished IANTD instructor in rebreather, ice, mixed gas, and cave diving, as well as an HSE Pro Scuba media diver and registered diving contractor, Richard thrives in the most challenging environments—from ice caps to flooded caves.

Richard’s passion for documenting the aquatic world has fueled a career spanning high-end TV dramas, feature films, natural history documentaries, commercials, and even virtual reality content. He is renowned for his ability to design bespoke filming systems for remote locations and specialized image acquisition, ensuring that every frame is as captivating as it is technically precise. Whether it’s braving extreme conditions or creating magic in a heated studio tank, Richard’s dedication to his craft sets him apart. As an owner-operator, Richard also manages a vast inventory of cutting-edge underwater camera equipment, which he uses to elevate productions to new heights. With a portfolio that includes work for Netflix, BBC, and major feature films, Richard continues to redefine what’s possible in underwater cinematography.

FILMOGRAPHY AND HIGHLIGHTS

IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm6109444/?ref_=ext_shr_lnk

Underwater Cinematographer: Expert in feature films, TV dramas, natural history documentaries, and virtual reality content.

Extreme Environment Specialist: Filmed in ice caps, submerged caves, and remote aquatic locations around the globe.

Equipment Innovator: Designs bespoke filming systems and operates his inventory of underwater camera gear.

Diving Expertise: IANTD rebreather, mixed gas, ice, and cave diving instructor with decades of experience in marine exploration.

TV and Film Collaborator: Worked on major productions, including Netflix’s Oceans series and BBC’s Casualty.

LINKS:

IMDb: Richard Stevenson

Website: richstevenson.co.uk

Email: [email protected]

Instagram: @richstevenson.uk

Tommy Vuylsteke

Underwater Cinematographer and Director of Photography

Belgium-based Tommy Vuylsteke is a highly accomplished Director of Photography and underwater cinematographer with a career spanning over 20 years. From commercials and documentaries to high-profile international series and blockbuster films, Tommy has brought his expertise and passion for underwater storytelling to productions around the world. A proud member of Cinediving and a recent Sigma Cine Pro, Tommy’s work is defined by technical mastery and a commitment to cinematic perfection.

Collaborating with a talented team of specialists, Tommy has built a reputation for excellence, capturing breathtaking visuals both in controlled studio environments and the open ocean. From sunken ships in icy waters to freediving sequences in the Bahamas, Tommy thrives on pushing creative and technical boundaries.

HIGHLIGHTS:

International Productions: Extensive filmography includes work on Luther: The Fallen Sun, Zillion, Baptiste(BBC), Kursk, and State of Happiness 2.

Studio Expertise: Frequently works at Lites Waterstage Studios, known for groundbreaking underwater cinematography.

Global Experience: Filmed underwater scenes in diverse locations such as Indonesia, the Bahamas, Malta, Norway, and Croatia.

Passion Projects: Combines technical precision with storytelling, as seen in long-term documentaries like his work with world champion freediver Alexey Molchanov.

Environmental Focus: Dedicated to nature documentaries and conservation storytelling, including filming for Our Nature in Belgian waters.

FILMOGRAPHY:

IMDb: Tommy Vuylsteke

Luther: The Fallen Sun (2022) – Underwater fight sequence with Idris Elba and Andy Serkis, Lites Waterstage Studios.

Kursk (2017) – Underwater camera operator for this feature film.

Zillion (2023) – Underwater cinematographer for this Belgian blockbuster.

Souls (German TV Series) – Underwater camera operator for scenes filmed in the UK.

Greenpeace (Commercial) – 2nd camera operator, promoting environmental conservation.

Our Nature (Belgium) – Months of filming pikes in their natural habitat for a nature documentary.

Bahamas Shark and Dolphin Movie (2012) – Documented marine wildlife over six months.

LINKS:

Email: [email protected]

Website: Blue Motion Pictures bluemotionpictures.be

Instagram: @Tommy_Vuylsteke

Stratis Kas, a Greek-Italian professional diving instructor, photographer, film director, and author, has spent over a decade as an esteemed Advanced Cave instructor, leading expeditions to extreme locations worldwide. His impressive diving achievements have solidified his expertise in the field. In 2020, Kas published the influential book Close Calls, followed by his highly acclaimed second book, CAVE DIVING: Everything You Always Wanted to Know, released in 2023.

Accessible on stratiskas.com, this comprehensive guide has become a go-to resource for cave diving enthusiasts. Kas’s directorial ventures include the documentary “Amphitrite” (2017), shortlisted for the Short to the Point Film Festival, and “Infinite Liquid” (2019), which explores Greece’s uncharted cave diving destinations and was selected for presentation at TEKDive USA. Kas’s expertise has led to invitations as a speaker at prestigious conferences including Eurotek UK, TEKDive Europe and USA, Tec Expo, and Euditek. For more information about his work and publications, visit stratiskas.com.