Human Factors

Errors In Diving Can Be Useful For Learning— ‘Human Error’ Is Not!

Errors are normal and can help us learn as long as we understand the kind of error we made, and how it made sense for us at the time. Conversely, simply attributing the cause of a diving accident to ‘human error’ is practically useless. Here Human Factors Coach Gareth Lock examines various types of errors and violations, and importantly the influence of the system in which they operate, and explains why simply citing ‘human error’ ain’t enough.

Text by Gareth Lock. Images by G. Lock unless noted. The Human Diver is a sponsor of InDepth.

The title of this article might appear to be an odd statement because there is a conflict; however, that conflict is intentional. This is because there is a difference between the term “error,” which can help us learn, and the attribution which people apply to the cause of an accident as ‘human error’ which doesn’t help anyone. In fact, if you see ‘human error’ or ‘diver error’ or ‘human factors’ as the cause of an adverse event, then the investigation stopped too early, and the learning opportunities will be extremely limited.

What is an error?

A few simple definitions might be

- the outcomes from a system that didn’t deliver the expected results

- an unintended deviation from a preferred behaviour

- something that is not correct; a wrong action or statement

To a certain extent, the precise definition of an error isn’t that important because whatever definition we use, we must recognise that ‘errors’ are never the cause of an accident, incident, or an adverse event, rather they are indicative of a weakness or failure somewhere in the wider system. If you are wondering what ‘system’ means in this context, it will be covered in the next section.

One of the key points to recognise is that an error can only be defined after an event. The reason for this is because if we knew we were going to make a mistake, a slip, or have a lapse, then we would have done something about it to prevent the negative behaviour/event from occurring! The terms mistake, slip, and lapse were specifically used as these are recognised terms in the science of human factors to describe the different types of variability in our performance.

Some Definitions

- A mistake is where you’ve done the ‘wrong’ thing but thought it was correct. Examples of this could be that training materials have changed but you’re teaching the old skill because you weren’t aware of the change, entering a wreck via the ‘wrong’ doorway thinking it was the correct one or surveying the ‘wrong’ part of the reef as some cues/clues for the location had been misinterpreted.

- A slip is an unintended action. This could be cross-clipping a bolt snap, writing the wrong gas analysis figures down because you transposed two numbers, or putting the diver tally number on the wrong peg on a boat board.

- A lapse is when we forget something. This could be forgetting the additional weight pouch needed for saltwater, not doing up the drysuit zip, or not going through the process to count all the divers back on the boat.

By breaking ‘errors’ down into these categories, we can develop mitigations to reduce the likelihood of them occurring on dives. For mistakes, buddy checking, co-teaching, QC/QA processes and debriefs all help us recognise when something isn’t quite right. For slips, we can design something so that it is harder to do the wrong thing. For lapses, we can use a checklist, buddy check, or physical prompt/modification to reduce the likelihood that critical items are not forgotten before it is too late. We can also look to modify the ‘system’ so that we are less likely to make an error, or if we do, we catch it before it is critical.

There is also an additional classification of errors called ‘violations’ which is where a rule of some sort is present and has not been followed. ‘Violations’ are also broken down into different categories too.

- Situational violation is where the context led to breaking the rule being the ‘obvious’ answer. This could be where a dive center manager tells an instructor to break the standards for commercial reasons or risk losing their job, or where a diver forgets their thermal undergarments and dives anyway because of time/money invested, or a wreck is penetrated without a line because the visibility appears fine.

- Routine violation is where it is normal to break the rules and potentially where it is socially more difficult to comply. Examples include not using written pre-dive checklists on CCR because no one else does, not analysing gas prior to a dive because no one else does, going below gas minimums because the boat crew make fun of coming up with ‘too much gas’.

- Exceptional violation is where breaking the rule is potentially safer than compliance. This might be rescuing someone below the MOD of the gas being breathed or going below gas minimums because you were cutting someone from an entanglement.

- Recklessness is where there is no thought or care for the outcome. In hindsight, many think this is present in some cases. However, in my opinion, if divers genuinely thought that their dive would end up with a serious injury or fatality, they wouldn’t do it. As such, there are weaknesses in education or self-awareness.

With the exception of recklessness, violations also provide opportunities for organisational learning. What is it about the rule that meant it was harder to follow? If rules are consistently being broken, it is not likely a person thing, but rather a situational or contextual thing that needs to be addressed. Investigations shouldn’t stop at the rules that were broken, as it is likely that they were broken before, and an adverse event didn’t happen then.

Terms like ‘loss of situational awareness’, ‘complacency’ and ‘poor teamwork’ are just other ways of expressing a general term like ‘human error’.

All these types of ‘errors’ within the system provide learning opportunities, but only if they are examined in detail and reflected upon to understand what was going on at the time.

What do you mean by ‘system’?

A system is a mental construct or idea used to describe how something works in an environment. In human factors terms, this is where humans are involved with technology, with paperwork, with processes, within physical, social, and cultural environments, and with other people. A diver who is on a boat using open circuit SCUBA about to enter the water with their teammate and dive a wreck in 50 m/170 ft is part of a system. The system they are within contains:

- Equipment designed and tested against certain standards.

- Compressed gas from a fill station which has protocols to follow making it safe to breathe.

- Training from multiple instructors using training materials from different agencies following high-level standards from a body like the RSTC or RTC, each of which has a QA/QC process in place.

- Protocols from the boat’s captain based on national and local maritime requirements.

- A dive computer that has decompression algorithms developed and refined over time.

- A cultural and social environment that influences how to behave in certain circumstances.

- A physical environment consisting of surface and underwater conditions.

- A wreck description that was drawn on a whiteboard on the boat, with a brief delivered by a guide explaining what is where and when to end the dive.

- Personal and team goals/drivers/constraints which have to be complied with or are shaping decisions.

- Multiple other divers and dive teams on the same boat who have their own needs, training, goals/drivers/constraints.

- Human bodies with their own individual physical, physiological and psychological requirements and constraints.

- The boat crew and their competencies and experience.

This list is by no means exhaustive but gives you an idea of all the ‘things’ that go into a system and those ‘things’ that might have weaknesses within them. Addressing these weaknesses and developing strengths are respectively what the science of human factors and resilience engineering are about.

When something goes wrong, why shouldn’t we use ‘human error’ as a cause?

There are a few problems with the term ‘human error’ as a cause.

- Firstly, it is a bucket that we can put all the different sorts of performance variability into without understanding what we can do to prevent future events. We will all make errors, so saying to divers ‘be careful’, ‘pay more attention’, or ‘be safe’ doesn’t help identify the factors that lead to the errors. These are the error-producing or latent conditions that are always there but not always together and don’t always lead to a problem. e.g., time pressures, incomplete briefing, equipment modifications, equipment serviceability, inadequate communications, flawed assumptions, and so on.

- Secondly, due to the fundamental attribution bias, we tend to focus on the performance of individual divers or instructors, rather than look at the context, the wider system, in which they were operating. As there isn’t a structured way of investigating adverse events in diving industry (coming soon!) or even using a standard framework to work out ‘how it made sense to those involved’, divers often jump to the conclusion that the cause was a just part of being a human and was ‘human error’ or ‘the human factor’. This is far from the case as you can see in the ‘If Only…’ documentary.

- Finally, adverse events like accidents, incidents, and near-misses are the outcomes of interactions within a system, and we can’t deconstruct the problem to single failures of individuals, hoping to ‘fix’ them. If that was the case and the problem was just down to errant individuals, we’d have far more adverse events than we do because people are broadly wired the same way. Humans, as well as being a critical factor when it comes to failure, are also the heroes in many cases when the system they are within doesn’t have all of the information provided to be ‘safe’. As such, we need to look at the wider system elements and their relationships to look at both success and failure.

We want divers to make errors…

Conversely, there are times when we don’t mind people making errors (slips, lapses, mistakes, and some types of violations) during a training course or even during exploration. In fact, in some cases, it is to be encouraged. The reason is that errors provide opportunities for learning. If we never make an error, we will never improve. Innovation means we are pushing boundaries against uncertainty, and with uncertainty comes the possibility that we end up with an outcome that wasn’t expected or wanted. By using trial and error, we have a better idea of where the boundary is. Self-discovery is one the most powerful learning tools we have because there is personal buy-in. Errors in training also help us solve problems in the real world, because the real world rarely follows fixed boundaries, and it is much better to fail in the training environment where you have an instructor with you to provide a safety net. Note, the instructors have to have a high level of skills/experience to act as this safety net!

Even when we don’t want divers or instructors to make errors, there will be times when things don’t go to plan. Experts are continually monitoring and adapting their performance, picking up small deviations and correcting them before they become a safety-critical event. This is why it is important to focus on and fix the small stuff before it snowballs and exceeds your capacity to manage the situation.

Fellow Human Diver instructor Guy Shockey uses the analogy of a Roomba (automated, robotic hoover) to explain this concept during his Fundamentals, Technical and Rebreather classes. The Roomba doesn’t know anything about its environment. However, over time, as it bounces its way around the house, it finds the locations of the walls, chair legs, table legs, doorways and other obstacles and creates a map of the boundaries. However, humans still have to help it when it comes to stairs as the top step doesn’t have a boundary, and it falls down! The ‘system’ solution is to put a ‘virtual wall’ in place so that the wall sensors can detect where the drops are.

What we are looking to develop during training, fun diving, and exploration is resilience. This is the capacity to adapt our performance and skills to deliver positive results when situations are changing around us, even to the point where we have an adverse event, but fail safely. Resilience provides us with:

- the ability to anticipate what might happen (positively and negatively),

- the ability to identify and monitor the critical factors to ensure safety,

- the ability to respond to what is going on around us, and finally,

- the ability to learn from what has happened in the past and apply it to future dives.

Resilience is developed from direct experience and learning from others’ activities and outcomes. We shouldn’t just focus on learning from negative outcomes though, we also want to know what makes positive ones happen, too.

Note, if instructors are only taught to follow a standard ‘script’ of what to do when, then when they or their students encounter something novel, they are more likely to have an unexpected outcome. That outcome might be ‘lucky’ (good) or ‘unlucky’ (bad). Experience helps stack the odds in our favour by building resilience. At an organisational level, sharing near misses and workarounds amongst instructors provides other instructors with this learned knowledge so that they are more resilient when they teach. Resilience doesn’t just exist at the individual level, it applies at the system level too.

In Conclusion

Errors are normal, and they can help us learn as long as we understand what sort of error we made and how it made sense for us to do what we did. This reflection isn’t easy because it requires effort. It also requires us to understand how we create a shared mental model within our team of what is happening now and what is likely to happen in the future (the key goal of non-technical skills development programmes).

We also need to understand the influence the system has on our behaviours and actions and look further back in time and space to see what else was present. Therefore, if we genuinely want to understand what led to the adverse events, we should spend time looking at what ‘normal’ looks like, the conditions that are normally present and what divers and instructors have to deal with, not just those that were present at the time of the adverse event. Accidents and incidents occur as deviations from normal, not just deviations from standards.

While ‘human error’ might be an easy bucket to throw the variability of human performance and its associated outcomes into, the attribution rarely improves safety or performance because it doesn’t look at the rationale behind the performance or the context associated with it. For that, we have to dig deeper and understand local rationality.

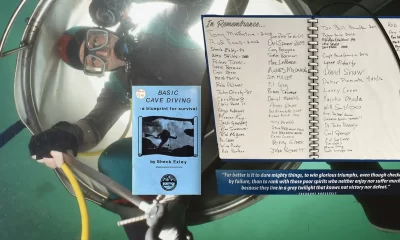

Gareth Lock has been involved in high-risk work since 1989. He spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force in a variety of front-line operational, research and development, and systems engineering roles which have given him a unique perspective. In 2005, he started his dive training with GUE and is now an advanced trimix diver (Tech 2) and JJ-CCR Normoxic trimix diver. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal of bringing his operational, human factors, and systems thinking to diving safety. Since then, he has trained more than 350 people face-to-face around the globe, taught nearly 2,000 people via online programmes, sold more than 4,000 copies of his book Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors, and produced “If Only…,” a documentary about a fatal dive told through the lens of Human Factors and A Just Culture.