Exploration

North, South, and Nowhere Warm

The first twenty seconds under polar ice decide everything—pain, survival, or transcendence. Ricardo Castillo’s journey from Mexico’s cenotes to the ends of the earth reveal the brutal beauty of cold-water diving.

By Ricardo Castillo

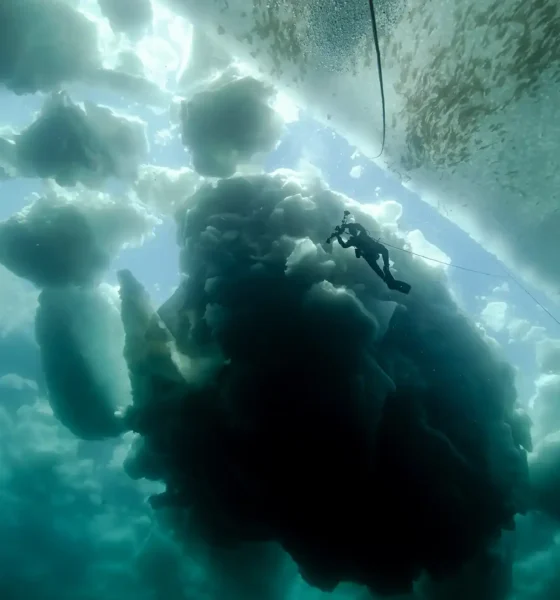

Lead image: At the meeting line between sea and ice, divers explore a shifting world alive with marine life. The site drops to 200 m (650 ft), where favorable weather that day allowed several dives close to the ice edge. The ice pack is always moving—at times trapping divers in until it’s physically pushed aside to reopen the entry and exit points. Photo: Ricardo Castillo

I always tell my students and friends that we are tropical fishes. In this corner of the world, anything below 20° C/69 °F feels like an invitation to hypothermia. In Mexico, we dive in caves and cenotes at 25 °C/77 °F, layered in thick 7 mm wetsuits and hoods. Even in the Caribbean’s warm 30 °C/86 °F, we wear full 3 mm suits. Drysuits? Not needed—optional curiosities for those who chase new challenges rather than warmth.

But how does a tropical fish end up diving in the coldest waters on the planet? Like many divers, I once believed mastery came from repetition—a thousand dives in the same reef or cave. But one day I realized that a true diver isn’t measured by familiarity but by adaptability. To dive anywhere, under any condition—that’s the real test.

So, I traded my tropical currents for frozen oceans. I learned to use a drysuit and set my sights on the poles—Antarctica, the Arctic, Iceland, Norway’s fjords, and the Great Lakes. What began as curiosity turned into more than a decade exploring the planet’s frozen frontiers.

“No hurry, no rush. Out here, if something goes wrong, it can go very wrong.”

Nothing prepares you for the first plunge.

When your head slips beneath the surface, protected by barely 10 mm of neoprene, your mind screams, “Get out! Run!” I’ve learned the rule: Hold for twenty seconds. That’s how long it takes to win the battle against the cold.

The shock dulls, the pain fades, and your skin numbs just enough for the experience to turn from torture to transcendence. The rest of your body stays warm under its layers, but the hands—always the hands—betray you. After thirty minutes, pain crawls in like electricity. That’s the signal that it’s time to ascend before the ache turns to agony.

“That first immersion was my baptism. It marked the moment I stopped being a tropical diver and became something else—a traveler between worlds.”

Antarctica

My first cold expedition was to Antarctica. We sailed from Ushuaia across the infamous Drake Passage, an 800 km/497 mi cauldron of wind and waves where the Pacific and Atlantic collide. The sea rose in walls 10 m/30 ft high, but ahead lay the white silence of the Antarctic Peninsula—mountains like cathedrals, glaciers breaking into the sea, light that never softens. Crossing the Antarctic Circle felt like stepping beyond the known world.

Everything there is giant: The scale of ice, the solitude, even the quiet—it humbles you.

Photo: Ricardo Castillo

The Arctic

When I returned home, someone asked, “What’s next?” I didn’t hesitate. “The North Pole.” At the time, I had no plan, only conviction. But logic—or maybe destiny—pointed north. A year later, I was standing on the frozen sea off Baffin Island, Nunavut, deep inside the Arctic Circle, where we lived for fifteen days on ice so thick it sang when it cracked.

If Antarctica is giant, the Arctic is majestic. The south is monumental; the north, intimate. Antarctica overwhelms you. The Arctic invites you in. There, I learned what it means to live on ice—to sleep, eat, and dive in a landscape that never truly sleeps, where the sun circles endlessly above the horizon.

Life Beneath the Ice

Diving in the poles is an act of devotion. Every descent demands precision. You are tethered to life by a single rope, anchored by an ice screw on the surface, your tender controlling the slack. Lose that connection and you’re gone—pulled beneath a twelve-foot ceiling of ice.

One day, under a massive iceberg shaped like an inverted pyramid, we almost paid the price. As we wrapped up a photo shoot, one diver’s line went taut—trapped under a ledge at 24 m/80 ft. The current had snagged it. I descended fast, dropped my camera, and braced my fins against the ice. Deflating my BCD, I used every ounce of strength to rip the line free. It snapped loose, shooting upward like a spring. Then my regulator began to free-flow. 80 ft down, under an iceberg, with 69 bar/1,000 psi left—every second was a calculation between fear and focus. I ascended carefully, following the shimmering rope back to light. At the surface, my gauge read 34 bar/500 psi. We exchanged looks that said everything: “That was close.”

Moments like that strip you down. They remind you that mastery in diving is not control—it’s surrender.

Our Arctic camp days began at 7 am and ended at around 10 pm—though the sun never truly set. Coffee. Briefing. Load the sleds. Ride out with our Inuit guides to find new ice cracks, pressure ridges, or drifting ’bergs to explore. The Inuit taught us to move with respect. “Never walk ahead of us,” they said. “You can’t read the ice.”

To them, the sea is life, but also danger. Invisible leads—cracks hidden beneath snow—can swallow a person in seconds. Fall in, and hypothermia will paralyze you before you can climb out.

They watched our dives with curiosity and disbelief. When we showed them photos of the underwater world—ice cathedrals, glowing blue caverns, forests of algae—they smiled, but I could never tell if it was admiration or confirmation that we were, indeed, insane.

“Never drink yellow ice,” one joked. Lesson learned.

Everything melts back into the ocean eventually. In these moments, daily life became ritual—suiting up, drilling holes, filling tanks at -10 °C/14 °F, sharing dinner in tents, laughing through the frost. The ice became both our enemy and our home.

The People and the Wild

One afternoon, we spotted a polar bear in the distance—nanuk, as the Inuit call it. It stood, sniffed, and then began running straight toward us. The guides shouted, “Go!” We jumped onto the snowmobiles and sped away, hearts racing, cameras still firing. From a safe distance, we watched the bear cross the ice like a white shadow.

To the Inuit, nanuk is sacred—a symbol of strength, survival, and balance. Hunting it is a ritual bound by deep respect. Seeing one up close was like meeting the spirit of the Arctic itself—beautiful, powerful, indifferent.

Underwater, the world transforms. In Antarctica, the sea teems with life—penguins torpedoing through icy corridors, leopard seals gliding in silence, krill swirling in clouds that feed whales and fish. In the Arctic, life begins smaller. In the brine channels of sea ice, microscopic algae bloom, feeding plankton, then fish, then whales—the entire ecosystem suspended in frozen veins of light.

Under the ice, life begins in the smallest places. Every dive is a glimpse of a hidden rhythm that’s both fragile and eternal.

The ice changes you, physically and spiritually. The sun burns your skin; the cold burns deeper. Frostbite scars fade, but the cold never leaves you. Even months later, you can still feel it inside your bones, as if the Arctic air has taken up residence there. The fragility of human life becomes undeniable. We are soft, temporary creatures in a place that endures without us.

The Inuit see their world differently. To them, outsiders who dive into the sea for “fun” are flirting with death. The ocean is not a playground—it’s an ancestor, a provider, a force to be respected. Their traditions—hunting seals, whales, and polar bears—sustain their families and preserve their culture. Yet the modern world often misunderstands them, condemning practices they don’t comprehend.

When outsiders turned these rituals into headlines and hashtags, the Inuit withdrew. Now they protect their customs in silence. The ice holds their stories, spoken only among those who belong to it.

The Fragile Frontier

No place on Earth is safe from us. The poles, once untouched, now bear the marks of our presence—pollution, warming, disease. On my last Antarctic expedition in 2025, I saw a new threat spreading: avian flu among penguins and seabirds. The impact was heartbreaking. Even here, at the end of the world, human fingerprints stain the ice.

“We are witnessing extinctions unfold in real time. The call is clear: Protect what’s left before it’s gone.”

Returning to warmth after weeks of frozen silence feels disorienting. The body returns; the mind stays behind. The marks fade. The frostburn heals. But the memories remain, suspended like bubbles trapped under ice. It’s impossible to explain to those who haven’t felt it—the weightless silence, the way the light bends blue beneath the surface, the humbling vastness of it all. Once you’ve breathed beneath the ice, you are never the same.

Icebergs melt, memories fade—but what we protect today may still exist tomorrow.

In 2026, I’ll return to the Arctic—this time to Norway’s frozen fjords—chasing once more that delicate balance between danger and wonder. Because once you’ve tasted the frozen world, you never stop hearing its call.

Essential Team and Equipment for Diving in Frozen Polar Waters

To dive in frozen polar waters, a highly skilled and trusted team is essential—divers must have proper training, teamwork experience, and the right mindset. Poor preparation can lead to serious consequences. Along with extreme cold-weather gear (thick jackets, base layers, snow boots, and hats), specialized diving equipment is required to ensure safety and performance in these harsh environments:

- Steel diving tanks – Preferred to offset buoyancy from heavy undergarments and denser polar water; often fitted with “Y” or “H” valves for redundant air sources.

- Regulators: Dive Rite XT1 first stage and XT2/XT4 second stages – environmentally sealed to prevent freezing and ensure reliable air flow.

- Buoyancy system: Dive Rite Arctic Wing (45 lbs lift) – designed for dry suits with thick insulation, providing stability and control.

- Backplate and harness: Dive Rite XT stainless steel backplate with TransPlate XT harness and an integrated 20 lb weight system.

- Mask and fins: Dive Rite ES155 mask and XT fins – durable and dependable for cold-water use.

- Dry suit: Custom-made flexible Kevlar dry suit from Mods with integrated boots, dry glove system, pee valve, 9mm hood, and interchangeable silicone seals; equipped with a Santi 303 thermovalve.

- Undergarments: Hot Chillys base layers, a Rofos Arctic Polartec one-piece undergarment, and a Santi heating system (Flex 2.0 vest and gloves) powered by a Santi 24Ah battery.

- Socks: Fourth Element Arctic socks for warmth and moisture control.

- Safety equipment: 45m (150ft) line reel with a surface marker buoy for ascent and safety stops.

- Dive computers: Two Shearwater units—a Perdix and a Teric—for redundancy and precision monitoring during dives.

Together, this setup ensures reliability, warmth, and safety when exploring the most extreme underwater environments on Earth.

Enjoyed this read? Here are more stories that tie into it.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Bringing Breathers to Antarctica — discusses using rebreather equipment in the extremely cold water and cold air of Antarctic environments. By Michael Menduno, original paper by Dr. John Heine (2019)

InDEPTH: Diving Tips & Tricks: Cold Water — practical advice for divers in cold water diving environments (bulkier exposure gear, working with cold hands, dry gloves, cold-water challenges) videos by Guy Shockey and Liz Tribe (2018)

InDEPTH: How Intrepid Souls Spent Their Winter Lockation — covers ice dives, cold regulator issues, freezing inflators, etc. InDepth winter special (2021)

InDEPTH: Freezediving: What Doesn’t Freeze You Makes You Stronger an article on freediving under ice, managing cold, diving in very cold or freezing water, and the mental / physical preparation needed, By Sabrina Figliomeni (2022)

InDEPTH: The Story of The Plura Cave Concert — With 69 divers in attendance inside the cave the whole event turned out to be a major success and was also awarded a Guinness World Record. (2024)

Research Gate: Scientific diving in Antarctica: History and current practice —overview of how diving is used in Antarctic research and the evolution of techniques in polar conditions. by Neal W Pollock (2007)

Science Norway : The deep blue Arctic Ocean: A scientific diver’s tales of life under water — a narrative / field report of diving under sea ice in the Arctic (Barents Sea region) by Mikko Vihtakari (2021)

InDEPTH: Into the Last Frontiers: Diving Shag Rocks and Antarctica — a recent expedition narrative of diving in remote Antarctic locations by Jeffrey Bozanic (2025)

Ricardo Castillo is a Mexican diver, instructor trainer, and expedition leader with 20-plus years and 7,000 dives behind him. From basic SCUBA to trimix CCR cave courses, he teaches the full spectrum while guiding expeditions into oceans, caves, and flooded mines worldwide. His camera has followed him to Antarctica, the Arctic, South Africa, Mozambique, the Mediterranean, Canary Islands, Maldives, Iceland, Norway, Hungary, Poland, Finland, the Great Lakes, Cocos, Galápagos, Bahamas, Truk Lagoon, Scapa Flow, Hawaii, Cuba, Tonga, Fiji, Thailand, Indonesia, and countless Mexican reefs and cave systems. Television crews often tap his expertise for documentaries on shipwrecks, sharks, and subterranean exploration. Holding instructor credentials with NSS-CDS, SDI-TDI, and DAN, he specializes in decompression procedures, mixed gases, rebreathers, and underwater imaging; his deepest dive is 137 m/450 ft, his coldest –1.7 °C/29 °F. Ricardo co-owns Dive Rite Mexico and Zotz Local Diving Experts in Playa del Carmen.

Links:

Email: ricardo@diveritemexico.mx

Website: https://www.diveritemexico.mx

Zotz Diving: https://www.zotz.mx

Personal site: https://www.ricardocastillo.mx

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ricardo.castillom.5

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/richardiving