Exploration

Deep In Italy’s Grecanica Wreck Valley

Explorer and equipment maker Andrea Murdoch Alpini takes us for a subsea tour of the shipwrecks littering Italy’s Grecanica Valley seabed.

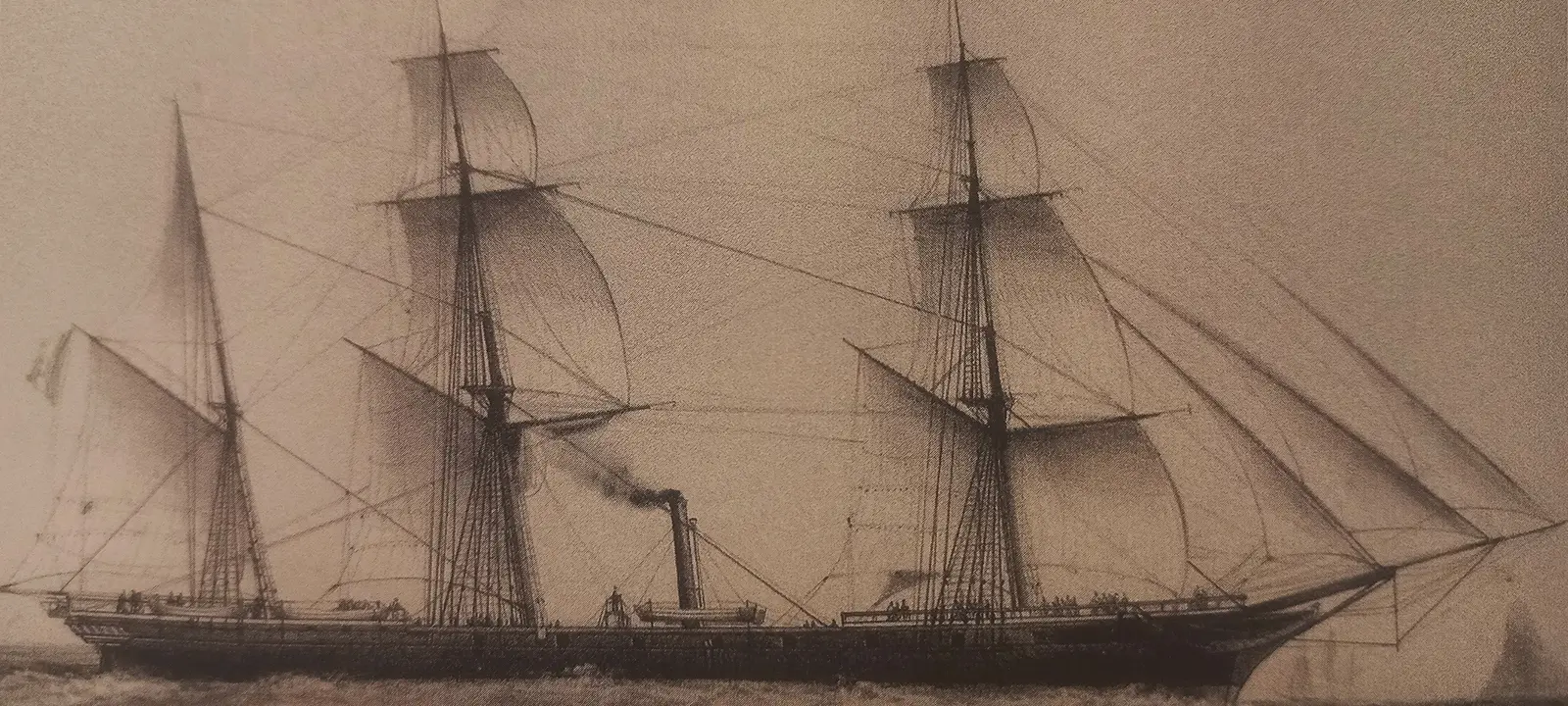

by Andrea Murdock Alpini. Translation from Italian by Marianna Morè. Pictures courtesy of the author unless noted. Lead image: The sailing ship Torino commanded by Giuseppe Garibaldi, sunk in 1860.

Sand dunes swept by the Ionian Sea winds. Villages built in stone and abandoned for centuries. Vegetation dried in the sun. Prickly pear bushes bearing thorny red, yellow, orange, or green fruits. This is the Deep South, the wild Grecanica Calabria: the Wreck Valley of Italy.

Looking at the nautical chart, below the Strait of Messina, a series of points have increased my desire for discovery. Every sign is a wreck. Every wreck is a story to be told. Are they all down there?

By diving, I can prove what I think is true.

Books, newspapers and archive sources are not enough to find the truth. You have to go deep to look, to study, to film. Sometimes I think that diving is more mental than technical.

The wreck van is loaded down with cylinders, helium, oxygen, booster, and compressor, all to be transferred to the Grecanica hinterland: the Wreck Valley. Today I leave aboard my zodiac, Raffio, equipped for submarine research and technical dives. I ask for authorization to leave the port of Reggio Calabria.

What I know is that the wind will change twice before I reach my destination.

The first change comes when we arrive at the Capo dall’Armi lighthouse: a beacon used by sinking ships during both World Wars to record their final coordinates.

A Glimpse Below the Surface

In 1916, the Cordova steamer Lloyd Italiano Società Anonima di Navigazione of Genoa was transformed from a steamer into a hospital ship.

On July 4, 1918, she was torpedoed near Capo delle Armi by the German submarine UC52. Until now, her wreck had not been located.

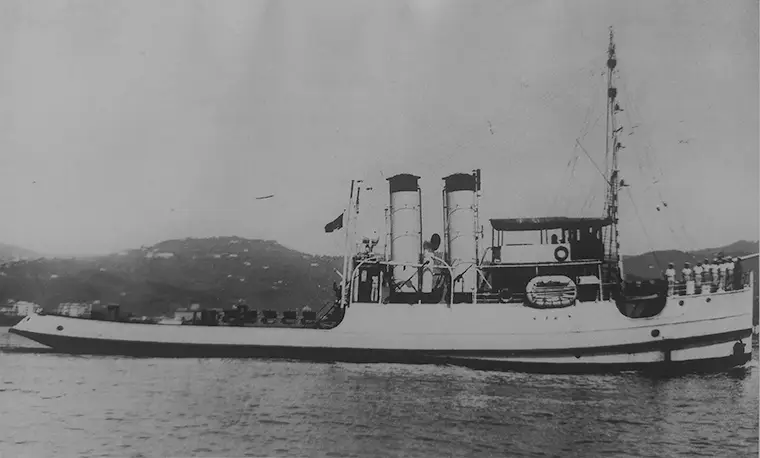

Further away from land, the Alfa ship was sunk, having been requisitioned by the Italian Navy in June 1940 and registered in the auxiliary navigation registers for external surveillance with the serial number V51. At 17:45 on August 30, 1941, the lethal British submarine Unbeaten sank her.

Traveling beyond the lighthouse and its beautiful cliff, I move toward the Saline Joniche.

Among the various wrecks that arouse my imagination is the tugboat Luni, about four miles from Capo delle Armi. The Luni’s story has always fascinated me greatly. It was the night of January 23, 1943. Before sinking, it was one of the two ships that towed the dying Motonave Viminale from Taranto to Messina. A well-placed shot from the British submarine Unbending delivered her to the seabed.

Back in 1891, the cargo ship Minna Schuldt was assembled in the Flensburg shipyards, then later converted to Marzamemi under the Italian flag in 1934. It changed hands between three Italian shipowners before yet another English submarine torpedoed it: the Triumph.

On March 5, 1941, Marzamemi sank with its load of sulfur. Today, the wreck rests on the submerged reef of Melito Porto Salvo, 50 m/164 ft deep.

Closer to land, a few mere strokes from the shoreline, is the hull of the steamship Torino, a ship which was used by commander Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Spedizione dei Mille campaign in Calabria to create the modern state of Italy.

A Seabed of History

At first light, the sand already burns our feet, and transferring equipment from the wreck van to Raffio takes time. The wind has not yet risen, so the surface of the sea is flat. The first point we reach is known: what remains of the Mergellina‘s bow. The ship was launched on commission by the Naples Steam Navigation Company in 1912, over a century ago.

From here, we set out to confirm stories, uncover facts, and explore new prospects.

From preliminary research, I learned that the German submarine U35 had torpedoed the Italian cargo ship Muggiano, which launched off the coast of Spartivento in 1906 in the homonymous shipyards and then was renamed Dandolo. The ship, a beautiful hundred-meter-long giant, was five thousand gross tonnage, and it sank, leaving few clues as to its whereabouts.

The research work on this trip is to remove many far-off wrecks from the list.

This is the case of the Sebastiano Bianchi, which sank after hitting a British mine laid by the submarine TRUANT. The ship disappeared on December 13, 1940. It is located at about 1,000 m/3,281 ft deep, ten miles from the lighthouse, quite a distance from the coast.

On the same land route, but a few miles further, is the wreck of the tanker Zeila. On March 23, 1943, the English submarine Unison torpedoed the Zeila four miles from Spartivento.

The Zeila, a ship just under two thousand tons of gross tonnage and over 70 m/230 ft in length, was launched under the name of Haliotis in 1898 in Holland.

One day, when I was moving toward land to enjoy the sea breeze, I went to the coordinates 37° 53′ N 16° 05′, where the remains of the ship Città di Bergamo, also lost during WWII, can be found. On March 14, 1943, she sank after being torpedoed by the English submarine Unbending. The wreck is to be recovered by the surface-supplied divers.

Today on the seabed, many parts of the ship remain that still make it perfectly recognizable. The current here is always absent, and the ship, built in the UK at Newcastle Upon Tyne shipyards in 1914, can often be seen in its entirety from the surface of the water. The water is transparent at this site, so much so that you can see the wreck, almost as if you were diving.

The Bosforo sank during the First World War as well, not far from the Capo Spartivento lighthouse where she lies at a depth of 63 m/307 ft. The fated Bosforo exploded and broke into three sections on January 12, 1918. The Austro-Hungarian submarine U28, under the command of Zdenko Hudecek,was responsible for the Bosforo’s demise. Nine crew members and twenty-seven passengers died in the explosion.

The Italian ship was sailing from Naples to Greece, having been built in 1878 in Glasgow, Scotland at the outbreak of the war. The Bosforo was part of the SITMAR fleet, or Società Italiana Servizi Marittimi.

While diving, I am fortunate to find the old temper of a ship that has not aged. This truly unique wreck appears graceful in all her shape and, in order to be fully appreciated, deserves many dives.

There are two other big wrecks that sank around here. I collected information and documents on their stories. It will take some more time, but soon we will find the answers we are looking for, and two new stories will emerge from the seabed of the Ionian Sea.

With its breathtaking landscapes, clear warm water, and wrecks at many different depths, tech divers from all over the world can now enjoy this wild Italian paradise in the Mediterranean. I’m waiting for you aboard Raffio so that we can dive together in this fantastic sea.

DIVE DEEPER

Other stories by the prolific Andrea Alpini Murdock:

InDEPTH: The Aftermath Of Love: Don Shirley and Dave Shaw

InDEPTH: Finessing the Grande Dame of the Abyss

InDEPTH: I See A Darkness: A Descent Into Germany’s Felicitas Mine

InDEPTH: Stefano Carletti: The Man Who Immortalized The Wreck of the Andrea Doria

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and PSAI technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor trainer based in Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming, and writing. He was awarded the Golden Trident as scuba explorer and researcher in June 2024.

Andrea holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. Andrea is also the founder of PHY Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophy of wreck and cave diving.

He published several books, Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti (2018) and his next, IMMERSIONI SELVAGGE, was published in the fall of 2022. Recently he published a new wreck-historical book: ANDREA DORIA: UN LEMBO DI PATRIA (2023). On Christmas (2024) a new book will be issued: NOMADE DEL PROFONDO, with stories of cave/mine diving, wrecks and three American interviews to ‘the oaks’ of the pioneering contemporary scuba diving.

He runs explorations on deep south wrecks of Italy on board his Raffio.